Interview with 2018 NBCC Criticism Award Finalist Edwidge Danticat

For the past four years, the National Book Critics Circle has partnered with The New School’s MFA Creative Writing program, allowing the students to interview each of the NBCC Awards Finalists. In addition to building excitement for the Awards Finalist Reading and Ceremony held at the New School March 14th-15th, these interviews have built an intergenerational bridge between the writers of today and tomorrow.

This year, as part of the ongoing collaboration, and in support of the NBCC’s conversation about reading, criticism, and literature that extends from the local to the national, Brooklyn Magazine will publish and promote the interviews between NBCC Finalists and the current students of The New School.

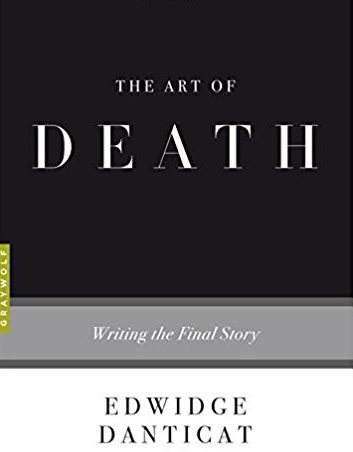

Edwidge Danticat’s essay collection, The Art of Death. Courtesy of Graywolf.

I was drawn to Edwidge Danticat’s NBCC Award Nominated Book, The Art of Death: Writing the Final Story (Graywolf), from the second I laid eyes on it. The book is small, chic, but inside it’s jam-packed with advice for writing about one of life’s most difficult topics. She states in the book’s first chapter, “I have been writing about death as long as I have been writing,” and from her debut novel Breath, Eyes, Memory (1994) to her NBCC Award Winning memoir Brother, I’m Dying (2007), she’s proven one of the best ways we can understand death is through reading and writing about it.

The Art of Death is a masterful addition to Danticat’s body of work. From the painstakingly thorough reflection on her own mother’s death to the literature she so flawlessly references, I’ve yet to come across a book as helpful on writing about death as this one. I had the great opportunity to talk to Danticat about writing The Art of Death, returning to New York, her mother’s home, for the NBCC Awards, and about the importance of keeping the stories of our loved ones alive.

First off, how did this book come about?

The wonderful poet, Kima Jones, interviewed me then sent me the book, The Art of Recklessness. I read it and loved it. I had never heard of “The Art of…” series before, so I got every one of them and started binge reading. It was such a great series, and I thought that if you read the whole series it was like having an MFA. I knew I wanted to write something about my mother and thought this would be a good way to do it. I was at the airport in New York at the time and I wrote this one-page proposal. I thought, I have to do this, I want to do this, I need to do this.

I loved what the New York Times says about the writing in The Art of Death, how you write this book with a “reader’s passion and a craftsman’s appraising eye.” One of the first things that struck me was the amount of literature you reference throughout. Did you have these passages set aside beforehand, or did you seek them out in the process of writing the book?

After my mom passed away in October 2014, I was at this point where I felt empty. I had friends who sent me things: a book of poems by Lucille Clifton; C.S. Lewis’ A Grief Observed; people would also send poems and things of that nature. So I just started reading. Most of the books I mention I had read before, but I wanted to go back to them with my grief in mind.

Reading and rereading those texts, for me, was very comforting. I knew I was going to have to write about my mother in some way before I could write about anything else, but I didn’t want to write about it the way I did my father in Brother I’m Dying, then this opportunity came and I thought this would be the perfect opportunity to do it, to do something that had a very clear structure and at the same time: it would allow me to talk about my grief and some of the books I was drawing comfort from.

Of all the books you reference, do you have one you consider your favorite or found yourself returning to more often than others?

Definitely the Lucille Clifton poem I reference, “Oh antic God / return to me / my mother in her thirties.” A friend sent that one to me soon after my mother passed away. That one really, really, struck me because I was not with my mother for most of her thirties; she was here in the U.S. and I was in Haiti with my aunt and uncle. Reading it, I just had that longing doubly so.

To imagine my mother young, I felt like the whole enterprise was something that, ultimately I wouldn’t be able to have. I wouldn’t be able to have my mother in her thirties, but often, when writing something, having a task that you know is impossible and trying to get as close to something as possible is a wonderful challenge. It’s something that keeps the act of writing it fresh and exciting; you have a quest that is, maybe, impossible. I couldn’t get my mother back, but I felt like there were some things that I could memorialize in this process and then put her death in the company of these other deaths that are just as epic.

Death is one of those things that, it happens every single day, but when it happens in our life, it feels new, it feels like it’s never happened before.

You talk about that in the chapter “Dying together,” when you focus on the mundaneness of death. You write, “The more I get to know the dying person on the page, the more likely I am to grieve for that person.” You do such a wonderful job of giving your readers the opportunity to really know your mother. What advice would you give to someone writing about a loved one’s death if they were to ask how to make that person’s life more vivid on the page?

I realized that sometimes when you know someone very well, it’s easy to assume that the reader knows them too, and you might quickly go to these short hands that you did with family members assuming (your readers) already have a pool of information. With my mother, I tried to go and talk about aspects of her that even people in our family may not have been aware of, like her really biting sense of humor.

Go to those singular things about that person that might surprise. Things that you know, but that might surprise even the people that already know them. With my book, I’m trying to convey that about my mother. I think you have to write about the people with nuance and not be afraid to show all the different sides of them.

The last time you were nominated for an NBCC Award, you won in autobiography for Brother, I’m Dying, about your father and uncle’s deaths. Was it special to also learn you’d been nominated for this book about your mother?

My editor wrote me and told me I’d been nominated, and I said, “What! Are you sure?” and in criticism, too! I was really, really surprised. But I was so happy. Sometimes when you’re nominated for these things you want to sound sophisticated, right? But I was overjoyed, I’m still overjoyed, and whether I win or not, I’ll still be so thrilled.

It feels like a gift from my mom. It’s like she keeps giving me things. It’s totally emotional, like I’d done this thing with my mother and now we’re both recognized for it. I didn’t expect it at all, but those are the best kind of surprises.

And with the awards taking place in New York, where your mother lived, will that add to the moment?

In the past, every time I would land in New York for whatever I was doing, I would always call her as soon as I landed. The first year (after her death) I would burst into tears, I would pull out my phone to call her, and I’d just remember everything again. I know she would have come to the awards; it feels like my mom’s arms are going to be around me.

One line that really stuck with me was, “I know now, having watched my mother die, that death is a phenomenon of both the body and the mind – her body and her mind, and now mine too.” Reading that left me with this feeling of responsibility to carry on the dead’s legacies after they’re gone.

At the end of Mary Gordon’s memoir she said ‘This is all I have to offer.’ I’m paraphrasing Gordon talking about her mother, but that’s the feeling I had. You’ve given everything to me, and this is all I’ve had to give you. Every parent is different and special, but my mother had come on this incredible journey and made so many sacrifices. My mother had sacrificed so much of her own life, I just felt like, this is what I can offer her. I felt that my responsibility was to not forget and not to let my children forget.

When I first heard Donald Trump’s comments about Haiti last month, you were one of the first people who came to my mind. Does the current political climate fuel your urge to share these very real and personal stories about your family and about Haiti?

We shouldn’t even have to do it, but we live in a climate where human beings are dehumanized every day. The places they come from are talked about like they’re not actual places, like there are not actual people living in those places. I think every personal story counts. It’s why I decided to tell my uncle’s story in Brother, I’m Dying, when he died in immigration custody. I think that’s probably the thing that all of the writers who are nominated for this award have in common: we all want to tell a story that, had we not told it, our lives would have not been the same.

I’m watching a lot of the coverage of these kids who are speaking out after their friends were shot. They’re saying the same thing as a lot of the people who were in the same situation as my uncle; they’re saying, “We are people. We don’t want these deaths to be in vain. We don’t want this to happen to anybody else.”

The more stories we tell, the more important it is to highlight that behind the slurs, and all the scapegoating, we’re all human beings. And again, I don’t think it’s something we should have to do, and we may not convince the head guy, but it’s important to remind each other that we bleed, we love, we matter.

Edwidge Danticat is the acclaimed and best-selling author of several books, including the novels Breath, Eyes, Memory and The Farming of Bones, and the memoir Brother, I’m Dying. She’s received many awards and honors, which include the National Book Critics Circle Award for autobiography, two National Book Award finalists, the American Book Award, the Anisfield-Wolf Award, the Story Prize, the Dayton Literary Peace Prize, a MacArthur Foundation Fellowship, and others.

Header Photo Credit: The New York Times

You might also like