Interview with 2018 NBCC Criticism Award Finalist Camille T. Dungy

For the past four years, the National Book Critics Circle has partnered with The New School’s MFA Creative Writing program, allowing the students to interview each of the NBCC Awards Finalists. In addition to building excitement for the Awards Finalist Reading and Ceremony held at the New School March 14th-15th, these interviews have built an intergenerational bridge between the writers of today and tomorrow.

This year, as part of the ongoing collaboration, and in support of the NBCC’s conversation about reading, criticism, and literature that extends from the local to the national, Brooklyn Magazine will publish and promote the interviews between NBCC Finalists and the current students of The New School.

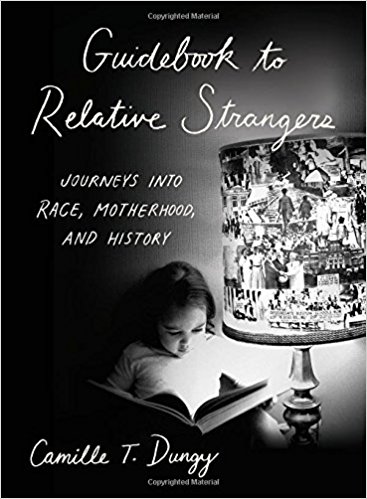

Considering that you are primarily a poet, Guidebook to Relative Strangers is your debut book of essays. It is my understanding that this book originally started out as a memoir, and transformed into a sort of traveling journal of your career as a writer and new role as a mother in the first few years of your daughter’s life. Was this outcome the direction you were always headed toward?

This book started the same way all my books do: I was curious about the world in which I found myself at a particular moment, and I started taking notes. These notes seemed to want to be organized in the manner you read now in Guidebook to Relative Strangers. I didn’t sit down one day and say, “I’m going to write a memoir.” I can’t imagine going about things like that, though I imagine there are writers who could.

I was keeping notes about my experiences traveling as a black woman and also about my experiences becoming a mother. I was working towards a deeper understanding of what was being revealed to me about who I was and who I was becoming, and also about who we were as a nation. These notes began to overlap and speak to each other and, after a lot of hours at the desk, the book’s path began to reveal itself to me.

What was edited out of it?

I initially thought that I was writing a book that explored motherhood. That was the new thing in my life at the time that I thought was the most interesting. I’ve been a black woman in America for several decades, and so my understanding of what it means to be black in America hasn’t really changed. The book does explore motherhood, but being a mother changed my approach toward my writing, my communities, and the world at large.

My daughter expanded my sense of commitment to hope, to possibility, and to actively working to build strengthening connections between vulnerable communities. To write about motherhood meant writing about why and how this was. I became more aware than ever of our vulnerability, so to write about motherhood meant to write about the past and present traumas that my black daughter and I must live with every day. This awareness of vulnerability is partly due to the presence of my child in my life, certainly, but it is also due to the awareness cultivated as a result of living a politically, historically, and environmentally conscious life for all these years. The edits in the book were about how I directed my attention, and my readers’.

What was the most difficult part of the transition from poetry to essays for you, and how did you triumph?

This wasn’t a difficulty I faced when writing this book, but when I first turned my attention to writing prose it would take me an impossibly long time to finish anything once I’d gotten past the first 5 pages. This was because I wanted to start every new writing day as I might with a poem. I would read everything I’d written thus far before I started the next new word. So, if I’d written a lot of pages, I’d find that I would spend my whole writing time rereading rather than writing forward.

With this project, I was constantly taking notes as I moved through the world. I journaled regularly on my trips around the country, and I found myself taking notes on a lot of the follow-up research that came out of things I discovered on those trips. I journaled about my daughter and the ways she was influencing how I saw the world and how the world saw me. While I was gathering the notes that would eventually develop into the essays in Guidebook to Relative Strangers, I employed the attention to every word I’ve trained as a poet, but I figured out ways that I could productively concentrate my attention on writing new lines to keep the energy moving forward.

You talk about language as a home. In essence, you have given your daughter, Callie, a place to live for the ages. What was an early experience where you learned that language had power?

At one point in the book, I wrote about the fine line between hearing a dog’s master say sic her versus it girl. There was a bully in my elementary school who liked to use his Dobermans to intimidate me. I learned about the fine line between those two commands at a very young age.

Language is the seat of so much power and, like all power, we get to decide whether we use it for good or ill. I can’t remember a time I haven’t known that. Perhaps because, as a black woman, I have always known how common it is for language to be used against me. I think I have also always known about this power because I have found great joy in language, in writing and speaking and thinking about the many things words can do to make the world a more beautiful and loving place. I would make it past that bully and his Dobermans and walk into a house where someone said, “I love you, beautiful.” I’ve always known that language can do revolutionary work in this world.

In my opinion, the design of your research process would be a great assignment for students to learn about how to form an inquiry and to share what defines how they are positioned in society today. I see this work as a perfect example of what everyone should try to write for him or herself. I believe that the world would be a better place if everybody did so. Do you see this work as a potential resource to teach young children about how to compose historical ethics?

I am honored that you feel this way about the book. I would be delighted to know that the book proved to be a resource for young people. I am equally delighted when grownups tell me that they learned things from what I’ve written in Guidebook to Relative Strangers. I am as tied to history as I am to the present. My sister is a historian; both my parents are history buffs. This sense that the past is alive and electric was a part of my upbringing I’ve decided not to escape. I am always curious about how we got to where we are today, and what the past can teach us about who we might become. I am willing to put the work in to dig up answers about the ways that where we have been has shaped where we are going. Thinking in this way seems to be crucial to thinking in an informed and honest manner about who I am in this world, who we all might be.

You might also like