Interview with 2018 NBCC Biography Award Finalist Edmund Gordon

For the past four years, the National Book Critics Circle has partnered with The New School’s MFA Creative Writing program, allowing the students to interview each of the NBCC Awards Finalists. In addition to building excitement for the Awards Finalist Reading and Ceremony held at the New School March 14th-15th, these interviews have built an intergenerational bridge between the writers of today and tomorrow.

This year, as part of the ongoing collaboration, and in support of the NBCC’s conversation about reading, criticism, and literature that extends from the local to the national, Brooklyn Magazine will publish and promote the interviews between NBCC Finalists and the current students of The New School.

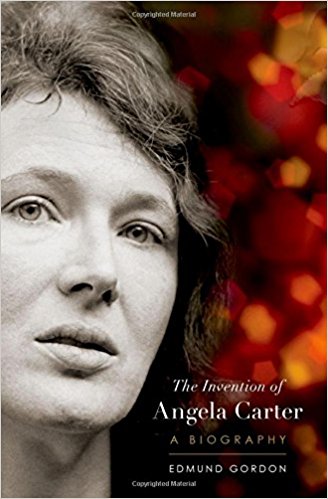

“Writers continue to be invented and reinvented by their readers, long after their own last words on the matter,” Edmund Gordon writes in his meticulously researched literary biography of the extraordinary English novelist, short story writer and journalist Angela Carter, who died from lung cancer in 1992.

An earth mother with “hurricane hair,” a “white witch” known for her feminism and magical realism, and one of the most important English writers of the last century. She’s all that and so much more. Gordon paints a lively, intimate portrait of this unconventional woman and her unconventional, chance-taking work.

Why were you so compelled to debunk the myth of Angela Carter as a “white witch?”

I suppose mainly because I wanted to do a sort of Carteresque job on Carter. She described herself as being “in the demythologizing business,” and aimed to unpack the myths of modern life—including the various myths of gender identity—to expose some of the cultural forces that had led to their construction.

I also think that “demythologizing” is one of the things that any decent literary biography should be trying to do. As I started to realize the extent to which her own life and character had become tangled up in mythology, I felt almost duty-bound to address it.

The details, the breadth of material in this book are astounding! How did you research it?

I began by re-reading all of Angela Carter’s published books, read through all of her journals, and all of the letters of hers that are archived in the British Library. I then set about interviewing as many of the people who’d known her as I could. I did a lot of travelling, and I got to hang out with some really fascinating people.

What about the writing and organizing?

I didn’t do much writing during that [research] phase. An odd paragraph here and there, but no sustained passages. My ideas for how to structure the book were constantly changing, and I was accumulating vast amounts of material. A writer friend recommended a computer program called Scrivener, and I used that to order some of my notes. I’d recommend it to anyone who’s writing a big, research-heavy non-fiction book.

Towards the end of the second year, I started writing. I had the idea by this stage that I was going to write 25 chapters of 5,000 words each. Most ended up being quite longer, but it was definitely useful to have that word-count in mind. It meant that I could think of each chapter as a discrete and manageable unit. I could kid myself that I wasn’t in fact writing a 500-page book.

With any kind of writing, I think it’s impossible to concentrate on the micro and the macro at once. You can’t keep the overall structure in mind while attending to individual sentence. As a basic principle of composition, I tried to make sure that everything in the book was relevant to the main narrative arc, which is about how Angela Carter became Angela Carter, and how she came to write the books she did.

How would you describe your writerly approach to, this book?

There’s currently a great vogue for biographies that take the form of an authorial quest, but I didn’t want to thrust myself into the foreground—I was conscious of how irritated a reader interested in Angela Carter might become if they found themselves wading through long passages about some guy they’ve never heard of. As a man writing about a feminist icon, that felt particularly urgent.

At the same time, I thought that there were interesting things that had happened during my research and I made the decision to put all that stuff into my epilogue. Anyone who isn’t interested in what happened after Angela Carter died is free to close the book at that stage.

That said, I think that the book is inevitably steeped in my voice and my point of view. On every page, I’m making decisions about how to narrate a certain incident, or how to interpret a certain passage, or which details to include and which to leave out. My rule of thumb was never to allow myself to speak without interruption for more than a paragraph or two at a time. I wanted the book to have a sort of polyphonic quality lots of voices, agreeing and disagreeing with one another, in order to fashion a composite portrait that I think is inevitably richer and more nuanced than a single perspective can ever be.

You beautifully illustrated your theme of “invention” by showing connections between the characters and plot in Carter’s work and experiences that happened in “real” life. Did you draw this fact/fiction roadmap solely by reading her journals and letters and published works?

There were several instances in which she flagged up a connection for me, such as the one between the world of The Magic Toyshop and the psychological environment of her childhood, which she spoke about quite frequently in interviews. If she did that, I tended to feel I was on pretty solid ground.

In other cases, such as the parallel between the short story “Flesh and the Mirror” and the incident with the Summer Child in Chapter 12, the similarities between events described in her letters or journals and ones described in her fiction were just too close to ignore. There were a few times when I saw some connection between the life and the work, and laid the evidence out without making a big fuss, and allowed my readers to make up their own minds.

You write that “All of Angela Carter’s books are about performance and self-invention.” As the book contains so many juicy passages from her journal, I began to wonder if she wrote them as if someone were reading. Is there something to the fact that she stopped keeping one after she was diagnosed with cancer?

I think she probably stopped keeping a journal after she was diagnosed with cancer just because she was exhausted from her treatment. She’d been keeping one far less frequently since the birth of her son in 1983 anyway. She certainly did perform for putative readers in her journal though. There’s a moment in the 1960s when she actually says: “Shit, I’m writing this for the reader over my shoulder.” And when she got ill, she had the opportunity to destroy all her journals: the fact that she didn’t, suggests she wasn’t averse to the idea of a biographer or someone else reading them at some stage.

At the same time, the way in which she writes in her journal is palpably different than the ways in which she wrote letters. I think she was performing a certain version of selfhood in the journals, but it’s a different and more private version than the one she performed in public. She very much believed that the self only really existed in performance; that there was no such thing as an essential inner self.

Your first introduction to Carter’s work was The Magic Toyshop. What would you recommend as a first read for aspiring writers, and what should we take notice of?

Her journalism collected in Shaking a Leg is consistently extraordinary. It functions as one of the most intimate and intelligent accounts of late 20th century Britain in print, as well as a riveting intellectual autobiography. Aspiring writers should look to it as example of how to modulate a voice: the way that she’s able to be angry and funny in the course of a single paragraph, even a single sentence, and to remain brilliantly stylish all the while, is enviable.

In terms of fiction, I’d recommend the short stories collected in The Bloody Chamber, which show just how much variety a writer of genius can squeeze out of familiar narrative modes, and Nights at the Circus, especially for the characterization of Fevvers, who must be one of the liveliest and most amusing creations in an English novel since the death of Dickens.

I was struck by the relationships and alliances Carter made with other writers and artists. Could you speak to some of these and reiterate what they meant to her?

When Angela Carter started publishing novels in the mid-1960s, she cut a very lonely figure in the English literary landscape. The only writer who was at all like her was Anthony Burgess, and he was her first real literary ally. Their relationship played out mainly via letters. It wasn’t until she returned to England from Japan in 1972 that she really became part of a literary scene.

By then, the English novel was dramatically changing—becoming more interested in imaginative and linguistic exuberance, and beginning to look outwards, to other cultures—and she formed very close friendships with a number of writers and editors, including Salman Rushdie, Carmen Callil, Lorna Sage, Kazuo Ishiguro and Neil Jordan. These friendships meant the world to her. They allowed her to feel like she had a certain status, as well as a decent number of allies, within the world of letters.

As you delved into Carter’s life, what most surprised you about her?

In terms of her personality, I was surprised by her lack of self-confidence in some respects. The sense of intellectual self-confidence that comes off in her books is so powerful that it was a shock to discover that she was often socially insecure, and that as a young woman she had a very negative perspective on her own appearance.

You created such an intimate and lively portrait of Carter—I feel like I know her having read the book, so I can only imagine how you felt, thinking and writing about her for more than 5 years. How do you describe that relationship? Was finishing the book like a sort of break-up?

More like a bereavement. I found the last chapter, in which I describe her illness and death, incredibly difficult to write. The relationship between biographer and subject is very weird: You get to know this person so intimately, better than you know most of your friends and family—in some respects than you know yourself—and yet the influence and attachment can occur in only one direction. You can’t speak to them, you can’t ask them anything. And yet you end up dreaming about them most nights. For many years, Angela Carter was like my imaginary friend, always there in my head, and I did feel quite lonely after I finished the book.

You might also like