Interview with 2018 NBCC Autobiography Award Finalist Thi Bui

For the past four years, the National Book Critics Circle has partnered with The New School’s MFA Creative Writing program, allowing the students to interview each of the NBCC Awards Finalists. In addition to building excitement for the Awards Finalist Reading and Ceremony held at the New School March 14th-15th, these interviews have built an intergenerational bridge between the writers of today and tomorrow.

This year, as part of the ongoing collaboration, and in support of the NBCC’s conversation about reading, criticism, and literature that extends from the local to the national, Brooklyn Magazine will publish and promote the interviews between NBCC Finalists and the current students of The New School.

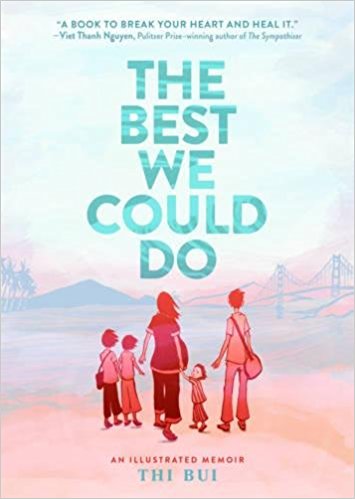

I first met Thi Bui at a panel on the graphic novel at BookCon last year. Though I didn’t know who she was, I was compelled by her narrative and bought her illustrated memoir, The Best We Could Do (Abrams Books). It tells the story of one family’s journey growing up in war-torn Vietnam and starting a new life in America, focusing on the relationships that form between parents and children.

When I crack the spine of my book, I see the message she wrote me when she signed it: “Best of luck with your religion + sex story!” Even then, I had a feeling we would be kindred spirits, and I couldn’t have been more right. Bui’s memoir is raw, emotional, and complicated.

Upon speaking with her, I was reaffirmed in my belief that certain human experiences, like being an immigrant, a refugee, or just Other, are universal.Bui’s next project will be about climate change through the lens of farmers in Vietnam. And in May, you can find her comic journalism piece on Southeast Asian deportation at TheNib.com.

In your preface, and in interviews, you talk about the many years and iterations this book has passed through before becoming what it is now. What made you start the project to begin with?

I took the opportunity to start it when I was doing my Master’s final project at NYU. It was about breaking down what I saw as really bad representations of Vietnamese people and narratives about the Vietnam War. There were all the bad Vietnam War movies that I’d grown up with, and then even looking further into scholarship about the Vietnam War, what I was finding a lot of was just very American-centric perspectives. And then even the ones that tried to not be American-centric did a very naive thing, which was to go talk to the enemy—and that was what people thought of as the Vietnamese experience. And I was like, “Hello! There’s a whole diaspora of Vietnamese people who were on another side of that war, so you might, you know, talk to us!”

It was just so frustrating that something so simple to me would seem so out of reach for so many American scholars. I did a whole master’s project around that, and then I also wanted to create something, so I did an oral history with the primary sources that were the closest to me, that I had access to, which meant my family. And my family’s reaction to reading the transcripts got me thinking, “There’s something to this.”

They were so excited to read their own words in writing and also to read each other’s stories, and to compare stories. They were more excited than they’d been about any kind of art project I’ve ever done before. I knew that I wanted it to be accessible. Reading Maus and Persepolis, I thought about comics as a more accessible medium that I had seen done.

I would say that the comic form is really conducive to that because you have the imagery that can really compliment your message so you can say less and somehow get more across. One of the things I actually wanted to talk about was that, in your memoir you give me such good education around Vietnam, like I actually now have a history about Vietnam and the Vietnam War that I never properly got at school, and in a way that’s resonant, that I understand.

Cool! Good. That’s the high school teacher in me.

From a craft perspective, as a writer myself, I really thought that came together quite beautifully and made your book a valuable resource in that sense. I wonder how you thought about putting those pieces together and laying it out in the way you did?

My brain is very abstract and full of symbols. My outline for the book was really not so much about plot but how each chapter was going to feel. In retrospect, I don’t know how my publisher ever agreed to do the book. There was a lot of back and forth with the editor.

I had a lot of material from interviews with my parents. And I’ve always thought about people giving oral history. But I guess, securing feedback from American readers early on, in the early chapters—they’d get confused about who was who, and is this Bo, or was it his grandfather, or was it his father? Just confusion about so many different characters made me realize that, just storytelling-wise, there needed to be a central protagonist that could anchor the story and help the readers through that I had to anchor myself. That’s how it became more of a memoir.

An interesting thing I observed is that pregnancy plays such a prominent role in this story. You bookend it with the birth of your son, and you also vividly depict each of your mother’s pregnancies. Was this meant to convey a deeper message around birth and rebirth?

For me, it was also very physical. Physical experiences have always been humbling experiences because they put you back in your body and help you connect with other people. Especially when you’re dealing with history and politics and immigrant experience, there’s a lot of academic discourse that can be quite “othering” and abstract, so it was important for me to bookend this story with a very typical experience, pretty universal and archetypal entryway.

I love the page with the identification pictures. I stared at them for the longest time of the entire book. It made it so real for me. Was that your intention in placing those photos?

The refugee camp photo is a thing that a lot of people have, still. It’s like a memento of that time—and it’s very, very real. The thing is, I didn’t want to introduce us with those photos. It was important for me to figure out the exact moment to reveal it. And I think that’s actually what makes it emotional for people—they spent the greater part of the book not seeing refugee photos. That was me thinking about how we encounter refugees today. We see the refugee photos first. We see them on a boat escaping from Syria or looking very impoverished in a refugee camp, and I think while those photos are meant to pull at our heartstrings, they also can divorce the person from their entire history. So you only see that person as a refugee and not the person that they were their whole lives up until that moment.

Similar to that idea, you made a conclusion at the end where you say that with the tumultuous history of Vietnam, you couldn’t really call it your homeland. I’m of Palestinian heritage and that was very jarring for me because, no matter how messy it is, Palestinians will always call historic Palestine home. So I was wondering if you could talk a little bit more about what brought you to that conclusion. What does that mean to you when you say that?

If the history of Vietnam had just been the history of Vietnamese people fighting against colonizers, then I’d definitely still call it my homeland even if I’d moved away for whatever reason, but because it was a civil war that ultimately tore it apart—a civil war that was made a lot worse by the Cold War and a proxy war, of course—really tears me up.

There’s a reconciliation that I yearn for, between both sides, and that includes the people who were really not about hiding at all but just trying to survive living in a country that was torn apart by civil war. I’m interested in the diaspora being able to connect with Vietnam as it currently is rather than living in a forever fantasy world based on nostalgia. I’m interested in healing.

So where would you call home now?

I don’t know. I’ve worked so hard at fighting for my right to be an American. I’ve always invested a lot in community organizing and being a public school teacher, and just trying to make my immediate community better—being involved in social justice work here in the U.S.

I think that a good move for the future is having more Americans, who are culturally really complicated, to understand world politics. There are lots of problems coming our way that don’t affect borders, like climate change for example. So I’m leaning towards the idea of being a global citizen.

You might also like