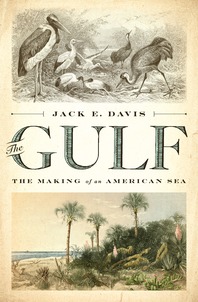

Interview with 2018 NBCC Non-Fiction Award Finalist Jack E. Davis

For the past four years, the National Book Critics Circle has partnered with The New School’s MFA Creative Writing program, allowing the students to interview each of the NBCC Awards Finalists. In addition to building excitement for the Awards Finalist Reading and Ceremony held at the New School March 14th-15th, these interviews have built an intergenerational bridge between the writers of today and tomorrow.

This year, as part of the ongoing collaboration, and in support of the NBCC’s conversation about reading, criticism, and literature that extends from the local to the national, Brooklyn Magazine will publish and promote the interviews between NBCC Finalists and the current students of The New School.

What is your primary motivation to write this book?

I grew up on the Gulf and wanted to write a cultural and natural history of a sea largely overlooked in the traditional narrative of American history. After the oil spill, I believed it was especially important to recapture the true identity of the Gulf, and to present it for what it is, which is more than an oil sump and sunning beach.

Did you choose the title, “The Gulf: The Making of American Sea”—and could you please explain it?

Yes, I chose the title. As I explain in the book, there are both historical and ecological reasons for why I call the Gulf, “An American sea.” When Thomas Jefferson completed the Louisiana Purchase, giving the US its first Gulf-front property, the Spanish, French, and British were freely sailing the Gulf. Jefferson and other elected officials believed the Gulf was rightfully an American sea, the control of which would solidify American dominion in the region. He wanted the US to acquire Cuba, and other presidents tried. Eventually, the US secured half the shoreline of the Gulf, sharing the other half with Mexico and Cuba, but the US has since controlled the sea, dominating the seafood industry and oil extraction.

As for the ecological reason, the Gulf is one of the richest estuarine environments in the world. Most of the freshwater that flows to the Gulf, and that is central to an estuarine environment.

The Gulf is a massive work with substantial history, topics, and other information. What did you do before you started writing?

I have been writing books since the 1990s. The Gulf is my third solo-authored book. I have also been a history professor since the 1990s. Before then I worked in the business world, attended college, and served in the Navy, which I joined out of high school because I wanted to go to sea and travel the world.

Could you please give a brief introduction of the history of the Gulf of Mexico?

My book is a history of the human relationship with Gulf nature over the course of nearly ten thousand years. It focuses on the five US states and gives most of its attention to the 19th and 20th centuries and how the American relationship with the Gulf evolved over time. The book is not just about people who lived beside the Gulf and their interactions with the sea, but how all Americans interacted with the sea, even from distant places. People of the Northeast and Midwest are just as relevant in the history of the Gulf as those who have lived beside it.

Your book has a unique perspective on exploring a landscape by digging into its history. You have published several environmental history books. What attracts you to combining nature and humanity?

Landscape is constructed by humans. I am interested in non-human nature as a historical agent, and how it has shaped the course of human history. Most historians treat nature as a physical backdrop to a human-driven story and disregard how nature impinges on human activities. I organized the book’s chapters around natural characteristics of the Gulf to emphasize the power and influence of the non-human world in the human experience.

In July 2017, Premier Oil said that about 1 billion barrels of oil had been discovered off Mexico’s coast. What will the oil discovery bring to the Gulf of Mexico?

In a word, controversy. More oil will mean not only more drilling and platforms over the water but an expansion in the onshore infrastructure that supports extraction. As I argue in the book, the real environmental damage from the oil and gas industry comes from the onshore facilities.

In your book, you discussed the growth coast, with houses, hotels, and condominium towers replacing vital natural vegetation in less than two decades. It has become a controversial topic of how can we balance environmental protection and economic growth. Could you please share your thoughts on this topic?

We know how to achieve that balance; we just don’t give it much priority. As a common practice, the Gulf states and others connected to the Gulf by rivers dumped raw sewage into the bays and bayous of the Gulf until the 1970s and the Clean Water Act. We nearly killed many of those bays, wiped out the greater majority of their seagrass beds—vital to healthy productive estuaries.

When we stopped and cleaned up these waters, they came back to life. More people live on these waters today, but nearly all are healthier than when fewer people lived beside them. Bird life I never saw as a kid, including the bald eagle, returned to Gulf shores because sea life was thriving again. We could roll back the Gulf of Mexico dead zone quite easily if we stopped sending agricultural effluent down the Mississippi River. We have learned to protect mangroves and coastal mashes and recognized the benefits to ourselves when we do.

What we lack is the political will to be smart about living with nature by not polluting it, not managing it, not altering it, not re-engineering it, not putting concrete and asphalt where the living shoreline should exist.

You might also like