Review of 2018 NBCC Autobiography Award Finalist Roxane Gay’s Memoir Hunger

For the past four years, the National Book Critics Circle has partnered with The New School’s MFA Creative Writing program, allowing the students to interview each of the NBCC Awards Finalists. In addition to building excitement for the Awards Finalist Reading and Ceremony held at the New School March 14th-15th, these interviews have built an intergenerational bridge between the writers of today and tomorrow.

This year, as part of the ongoing collaboration, and in support of the NBCC’s conversation about reading, criticism, and literature that extends from the local to the national, Brooklyn Magazine will publish and promote the interviews between NBCC Finalists and the current students of The New School.

I want to tell you about my skin or rather, the scars that pepper my skin. I haven’t been able to stop talking about them, writing about them, and photographing them since I read Hunger: A Memoir of (My) Body (HarperCollins) by Roxane Gay. My wounds are self-inflicted, but not in the way that you think. They’re the result of 20 years of picking at the little red bumps, otherwise known as chicken skin, that riddle my body.

Picking at myself started as a kind of self-soothing after my father left and eventually morphed into a way of saying, “You marked me and now I want to mark myself even worse.” They are a way of letting people know that while I can’t always say what happened to me, I can wear it on me always. Or, in the words of Roxane Gay, “I am going to keep telling them even though I hate having the stories to tell.”

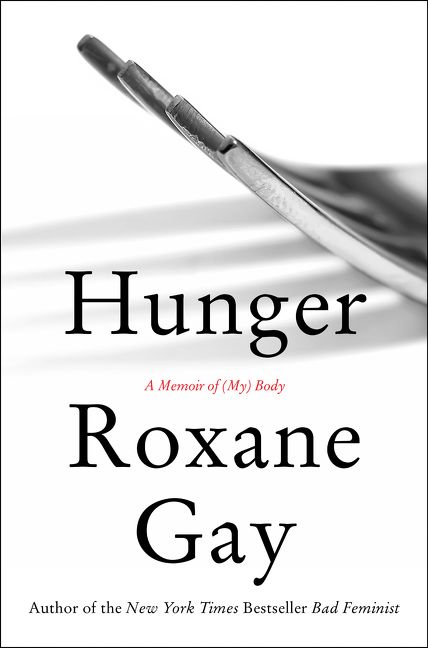

Hunger is a beautifully brutal read. In just over 300 pages, Gay ruthlessly takes the reader through the events of her childhood that led to her significant weight gain, the subsequent dieting, weight loss and weight gain cycle she has been in for over 20 years, and the ways in which she moves through a world that hates people with bodies like hers.

At the age of 12, Gay was gang-raped by a group of boys, including a popular boy she loved and trusted. Not wanting to bring her shame to her parents, hardworking Haitian immigrants, she turned to food. “I was hollowed out. I was determined to fill the void, and food was what I used to build a shield around what was left of me.” Soon after, she entered a private high school in New Hampshire, away from the watchful eyes of her parents, where she gained 30 pounds in two and a half months.

During the summers, Gay would attend weight loss camps or subsist solely on liquid diets, always at the suggestion of her well-meaning parents. She would return to school thinner and to praise from her classmates, only to be overcome with anxiety about the dangers of her shrinking body. That’s when she would gain all of the weight back and then some. This cycle continued into her college years, even when she left Yale in her sophomore year to move to Arizona with a man she met on the internet during what she describes as her “lost year.”

At her heaviest, Gay weighed 577 pounds. She has succeeded in making her body a “fortress,” a “cage.” Gay convinces herself that if she makes herself as big as possible, she will no longer be attractive to men, thus keeping her safe.

Interspersed with her own story of her “unruly body” are observations on how women are taught to hate their bodies from a young age. Between the celebrity endorsed weight loss commercials, the idea of the “revenge body,” and gossip magazines criticizing or praising women based on their weight, women are inundated with the notion that what we are is never enough, even when it is too much.

Hunger is not your typical survivor story. It is not just a memoir about the body but about the ways we learn to protect ourselves after trauma. Gay doesn’t consider herself a survivor, instead preferring the word victim, explaining, “I don’t want to diminish the gravity of what happened. I don’t want to pretend I’m on some triumphant, uplifting journey.” I sat with this explanation for a while, the way one does with any truth that’s difficult to swallow.

At one point, Gay wonders about the person she would have been if the day in the woods had never happened. “When I imagine this woman who somehow made it to adulthood unscarred, she is everything I am not.” And that’s the scariest thought, isn’t it? To imagine who you could have been without your trauma? Roxane Gay gave me permission to look at parts of my life and say out loud, “this is not okay.” She gave me permission to imagine a life where I don’t need to tear my own skin apart in order to not feel my father’s hands on it.

What Roxane Gay has achieved in writing “Hunger” is not only taking back her body, her story, but giving a voice, or some sense of courage, to other struggling women, both survivors and victims. We are all trying our best, to rewrite our story not for what it isn’t but for what it is, one body, one scar, one truth at a time.

You might also like