Interview with 2018 NBCC Criticism Award Finalist Kevin Young

For the past four years, the National Book Critics Circle has partnered with The New School’s MFA Creative Writing program, allowing the students to interview each of the NBCC Awards Finalists. In addition to building excitement for the Awards Finalist Reading and Ceremony held at the New School March 14th-15th, these interviews have built an intergenerational bridge between the writers of today and tomorrow.

This year, as part of the ongoing collaboration, and in support of the NBCC’s conversation about reading, criticism, and literature that extends from the local to the national, Brooklyn Magazine will publish and promote the interviews between NBCC Finalists and the current students of The New School.

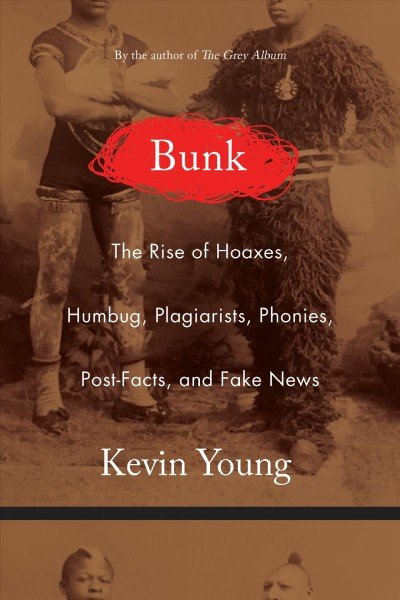

Bunk (Graywolf) is author Kevin Young’s deeply-researched book on the history of the hoax in all its forms, from humbug and plagiarism to “fake news.” The book relates these hoax phenomena to the major issues we face today, issues of stereotyping, race, and gender. It’s a deeply-affecting book that’s directly relevant to understanding our contemporary reality, and it offers a lens for moving forward.

What was your original motivation for writing the book?

I saw people talking about hoaxes but I felt like they didn’t seem to understand what hoaxes were really about. There was a lot of time spent talking about the blurry line between fact and fiction, or somehow were just joking when, in fact, they were quite serious in their use of these stereotypes.

From the first chapter, it was my impression that you’d written this book with a poet’s eye. Your close attention to the meanings and derivations of words, the often-humorous turns-of-phrases. Was this a conscious effort to style the book in this way?

I think it just happened that way. Besides the things you mentioned, I think I’m a poet no matter what I write but the advantage is, poets make metaphors, which is a kind of connection, and that’s what I was trying to do with this book.

Yeah, I definitely got that feeling immediately. A thread you follow throughout the book is the link between hoaxes and stereotypes, particularly related to race and gender. Can you talk a little about that?

I think a hoax is often making use of race and is always interested in the deep divisions that divide us, in society, and this is just one more example of using these stereotypes, but they’re just a form of cliché and shorthand that lets them not have to say much, but say it all.

A common quote cited about/from your book is that “race is the most dangerous hoax of them all.” I got the impression that these hoaxes you document feed on racism, but then race feeds back into the hoaxes, almost like an endless loop. Do I have that right?

Yeah. I think the hoax, like I said, makes use of race, but I also think race is a version of the hoax, in that it’s something that’s not real, but is something pretending to be true. That doesn’t mean that racism has effects, quite the contrary. I mean, that’s what’s even more pernicious about it, and even by the stereotypes you see used by it.

Since your writing and the publishing of this book, have your views changed in any way?

Not really. If anything, I see the ways the Russian bots make use of this kind of very thing, they are often pretending to be worse than things are, and also, make use of the very selfsame divisions that I was talking about in my book.

You mention in the acknowledgments, Bunk began as something from a personal experience, then expanded into this research-heavy result. Can you describe how that developed?

Yeah, I had written my first book, The Grey Album (2012), which was very much about black culture and tracing it from slavery to the present, the negro-spirituals to hip-hop, and I was thinking about improvisation and what I ended up calling “storying.” In many ways, the good side of lying. Then I started thinking a lot about the bad side of lying, and that was partially because I realized it wasn’t all fun and games.

The style of the book is what I would call “fluid.” It moves from one hoax to another, then another, and then you tie all of these [different hoaxes] to your larger themes. Was this a result of conscious planning or did it just come out that way?

I’d been writing about fake journalism and the ways such fakery could be dangerous, and then suddenly the term “fake news” was everywhere. The book was already finished and was actually coming out, so it was just fortuitous, and a little forward-looking in it’s approach.

I tried to weave in and tell a story that was a kind of history, but also one that reflected the present. So, once I realized that [P.T.] Barnum was going to start the book, I then realized, also, what was interesting about Barnum is his relevance to today.

This book really changed the way I see so many things. I have trouble, now, experiencing anything without questioning my own assumptions and even the intent of the person or object of art with which I’m interacting. What kind of reaction were you expecting from readers?

I don’t know. I’ve been pleased by peoples’ reactions. They seem to respond to [the book] and understand the history. I think that’s important and was really pleasing to see.

Looking forward, how do we as a country cope with this continuing tradition of the hoax in all its guises and the underlying assumptions about race, gender, and identity?

It’s an interesting moment. People are quite cynical and believe everything’s kind of hoaxing, which can lead to this feeling that “everything’s hoaxed, everyone’s faking.” My fear is that we’re in this half-hoax world, and that’s dangerous.

It’s better to be skeptical and questioning, but also to trust as much as you can, while evaluating. It’s a hard balance to strike.

You’re focused on non-fiction and memoir [in your book], but I’m wondering if you could talk about the hoax’s role vis-à-vis fiction. You mention that a lot of these hoaxes “render reality two-dimensional” and I’m wondering if that plays into the depiction of characters in fiction.

I think the danger of the hoax is that it doesn’t just threaten the truth, but also fiction and our ability to admit that we’re moved by things that aren’t real, which is very important. One of the things I think contemporary fiction is doing is playing with the idea of autobiography. It actually goes back to the beginnings of fiction, which often pretended to be autobiography, and here you have people writing autobiography almost pretending to be fiction. I think that’s really interesting, but I also think it’s a world away from hoaxing, and I tried to make that clear in the book.

I think that was clear, but I’m curious how a fiction writer deals with a lot of these hoax-related assumptions we make about people in our society.

The writers I like are thinking about these divisions and problems, anyway, someone like Jesmyn Ward, or my friend, Colson Whitehead. They’re writing beautifully about race in America, and sometimes they’re telling ghost stories, and sometimes they’re using fantasy. I think they’re engaging the full range of imagination in order for us to understand and imagine life in its fullness. And so, if anything, it means you have to be better at that, and you can’t just rely on notions that feel kind of true. Writers I know are much bolder than that, in creating worlds, but also helping us to understand this one.

Is there anything else, last call, something on your mind you’d like to share?

I’m struck over and over again by the way the hoax is political. I’m trying to understand that, and the way the hoax it can almost become a form of propaganda. That’s what’s important to fight against.

You might also like