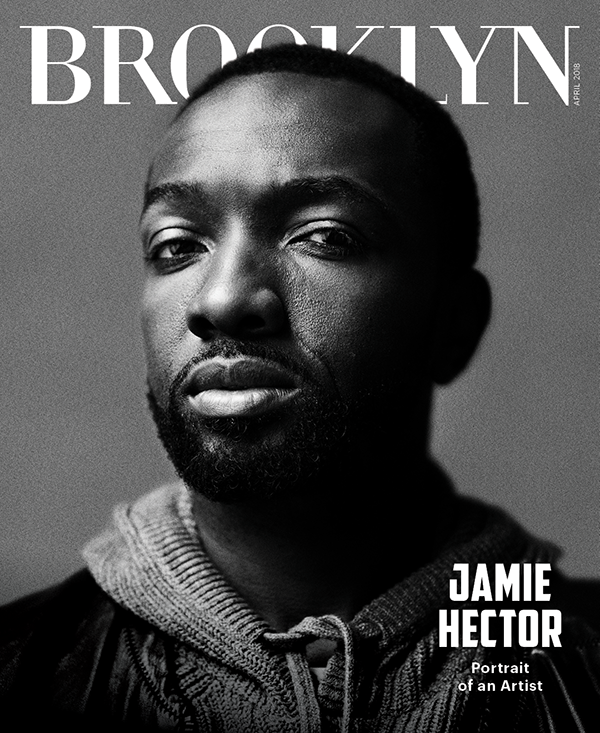

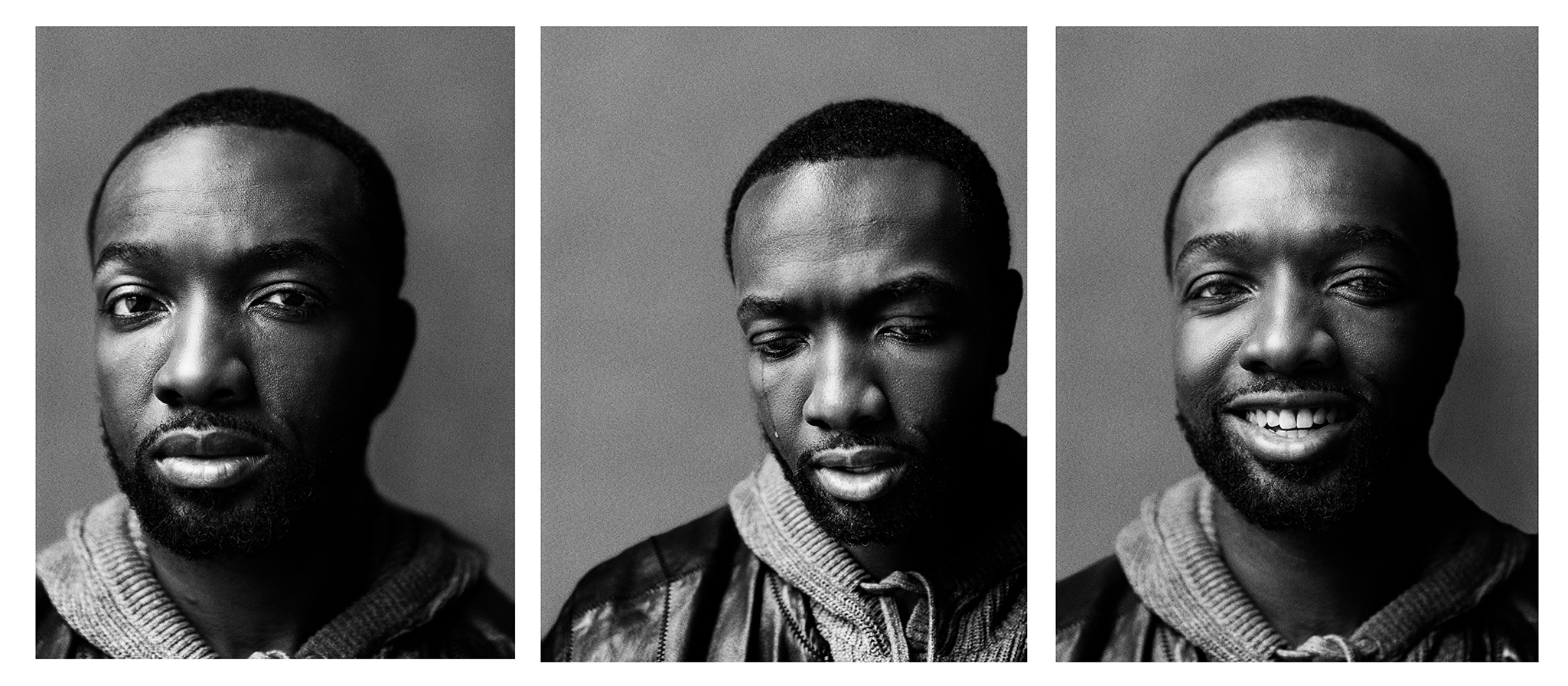

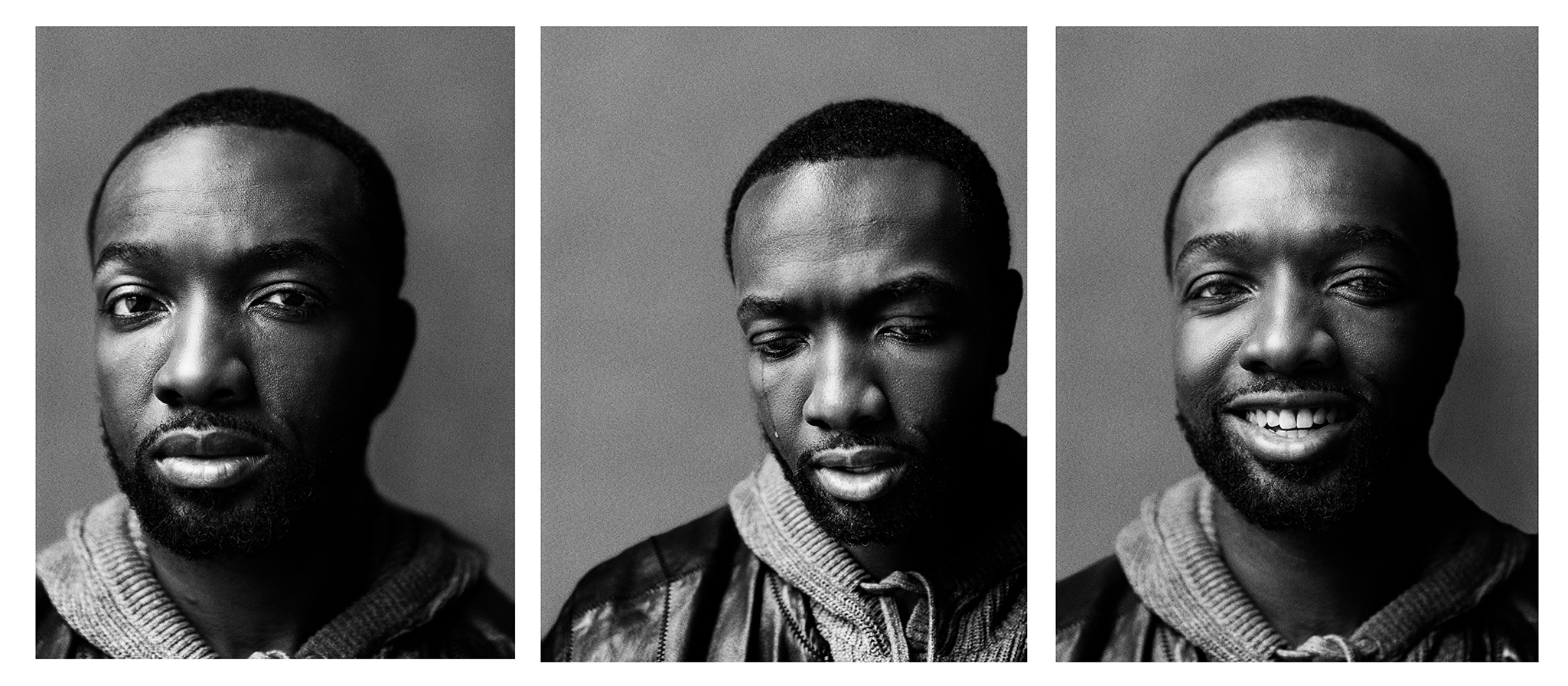

Jamie Hector: Portrait of an Artist

PHOTOGRAPHY John Midgley

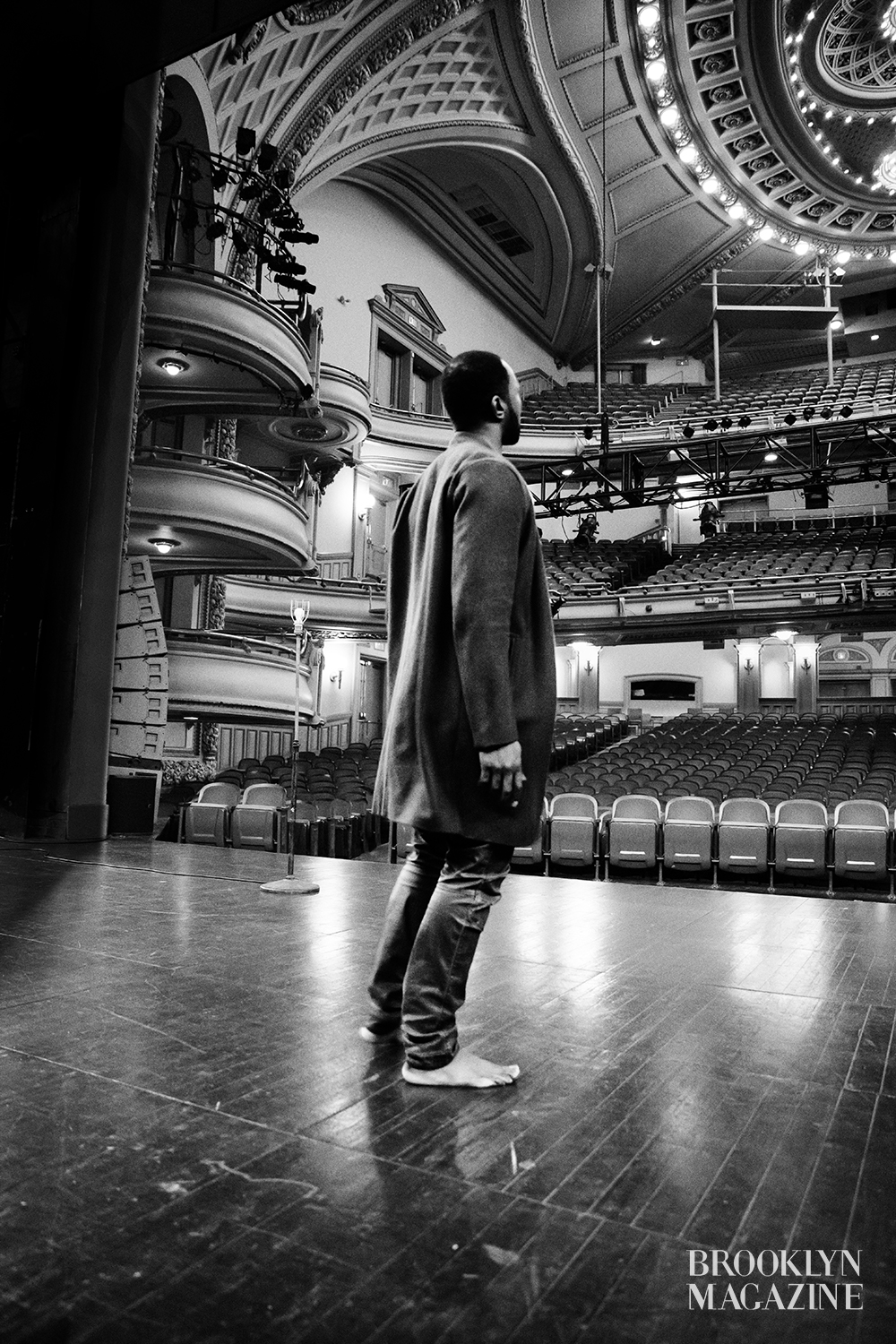

The first time Jamie Hector visited BAM, in Fort Greene, he was 21. As the youngest of seven to a Haitian mother—who worked as a nursing assistant—Jamie lived in Brooklyn his whole life. Repping East Flatbush and Crown Heights, he had heard about BAM, and even passed it a few times, but it was only after a friend invited him to see one of Tennessee Williams’ plays that it occurred to him that he could go inside.

Such is the case of many black and brown kids from the borough who don’t instinctively feel, and implicitly learn, that the borough doesn’t belong to them. This by no means suggests that BAM doesn’t open its doors to anyone who’d want to visit; but like anyone who wants to feel welcomed somewhere they’ve never been, they’d like to be invited. But the great irony of invitations, as Jamie’s life will illustrate, is: by the time you’re invited, you have already given yourself permission.

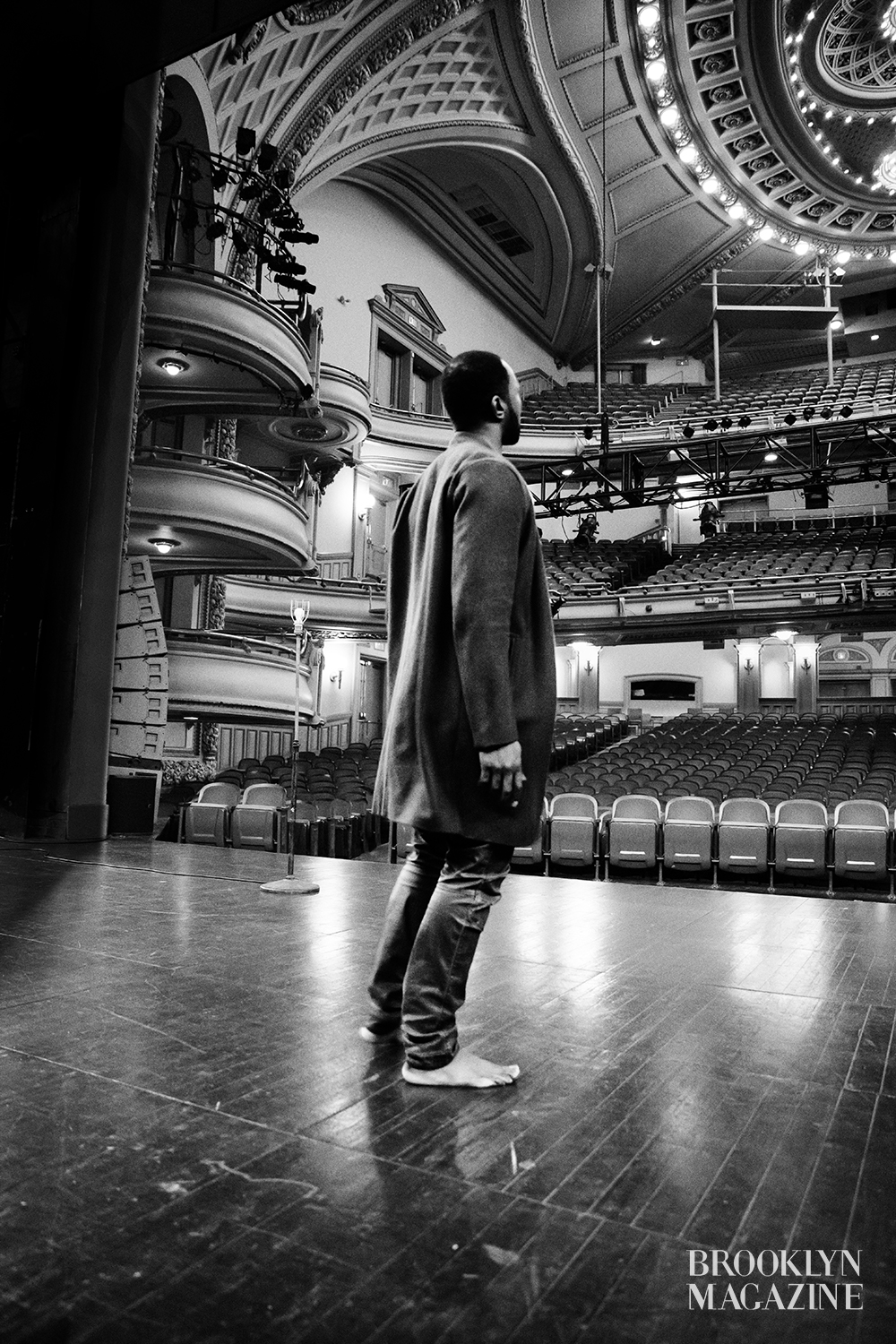

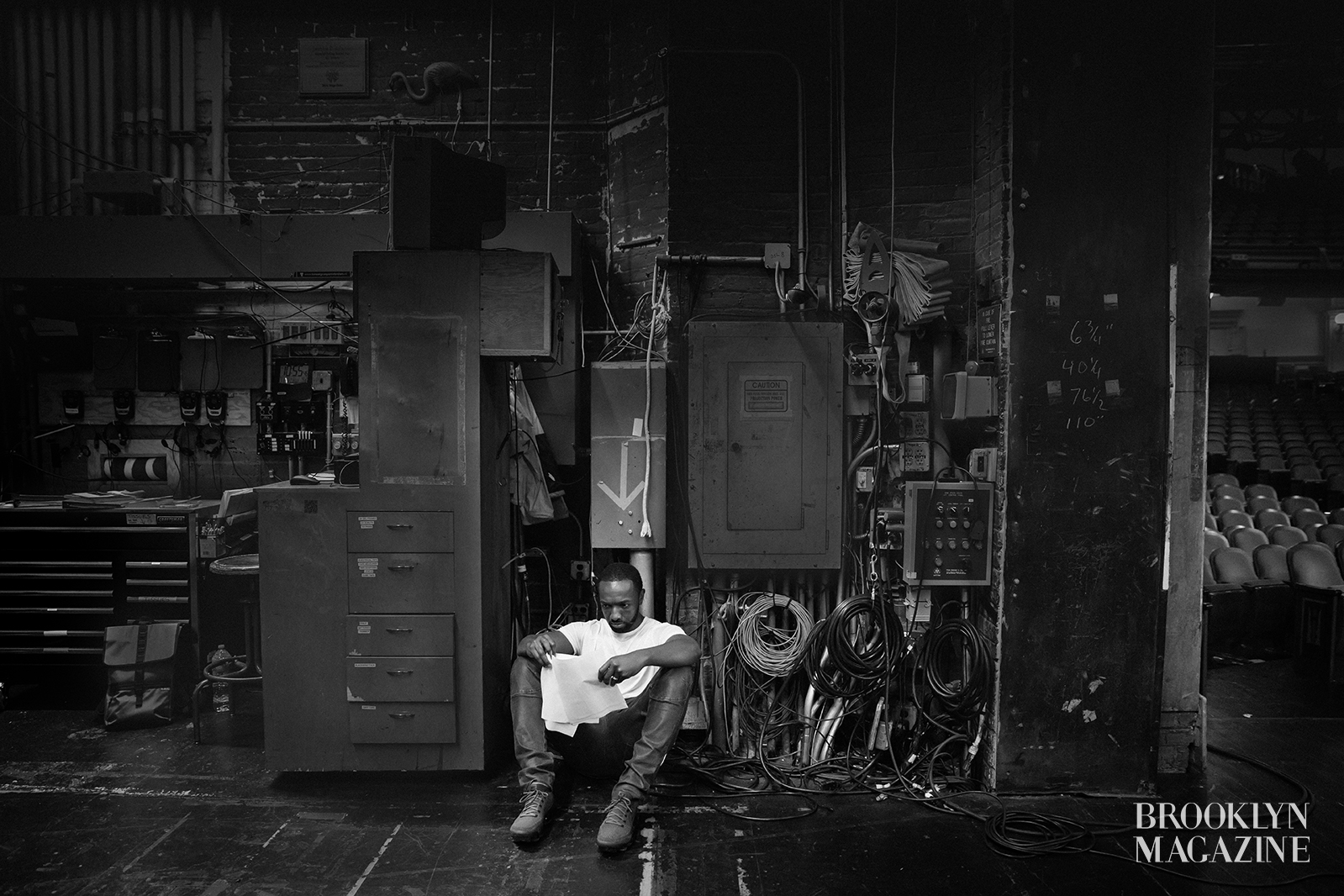

By the time Jamie had set foot in BAM, he already had four years of theater experience with Tomorrow’s Future Theater Company, excavating the depths of his soul to manifest the light that would ultimately make him a serious actor. When I say “serious,” I’m not only referring to those moments when the lights are hot, the cameras are on, and the audience is present; but those moments when there aren’t any lights, the cameras are packed away—save for John Midgley’s—and the only person there is the artist at work.

Coupled with this interview—where Jamie talks about the seriousness with which he takes his craft, how his role as Marlo Stanfield on The Wire put him in a prime position to give back to his community, and his role as detective Jerry Edgar on Amazon Prime’s Emmy-nominated series Bosch—these portraits, taken at BAM, illustrate an actor whose at home—on the stage, and off.

What does being an artist mean to you? Say, “I am an artist,” what are you really saying about yourself?”

I don’t associate everything with the ability to articulate things in an intellectual way. It’s visceral. It’s auditory. It’s feeling. When I was into music, I used to really enjoy putting words together. I used to rap when I was younger, and I used to love putting words together. But when I would listen to the music, I didn’t hear only the music. I kind of saw the notes, bouncing all over the place. It means really working on developing. On transforming. It means everything.

What was the moment you realized you were an artist?

There are two stories. I was about 17 when a friend invited me to a Theater Company called Tomorrow’s Future. The people working at the company asked me, “Can you do anything?” And I was like, “I can dance.” I got on stage and everybody was blown away.

That transitioned into stage and performance. Back then I spoke very fast. It was like Brooklyn 10x2. The people at the company just never understood a word I was saying, but they allowed me to be there, and develop as an actor. One thing led to another and I start getting parts onstage, which changed my life because then an audience of people wanted to see me work.

That’s when I went and studied at a small acting school called Weist-Barron-Ryan Acting when I was about 21. I’m doing theater productions around the country with Tomorrow’s Future Theater Company. Original plays and constantly performing, developing my skills, talents, my abilities at that theater company. And then, I’m like “okay, where do I go from here?”

What were the things that you saw in your own performances that let you know you weren’t performing like you could’ve?

Sometimes as an artist you sometimes need affirmation in some ways from a larger audience to tell you that you are a dynamic actor, or even to show you things that you already know. So just to hit the point, even under those circumstances, I still didn’t consider myself very committed to executing.

But something that really shifted in my mind when I was working at Weist-Barron, an instructor gave me a script for an attorney role and said, “Take some time, come back, and do a scene.” So, I come back ready to do the scene and begin doing the lines in this affected way. The instructor asks, “Why are you talking like that?” I say, “That’s how an attorney talks.” That’s when he says to me, “You don’t think there is someone that studies law that comes from where you came from?” Then he says, “Go out and do it again. Come back, and be yourself.” That changed it. Because then I saw that I could exist.

I navigated through it quietly. Nobody ever knew. I was just like, “I’m out.” I’d leave school, and my boys would be cooling out on the block. I give ’em a dap and be like, “I’ll be back at 2:00.” If somebody wanted to know, like when my boys eventually found out, I was like, “Come on down.” Some of them came.

Shoot for the theater companies after school. Go over there, get onstage, do what I do. Go home. My mother didn’t know. She thought I was at school, studying. Go through an entire process until one day I land a TV spot, then it’s just like what was New York Undercover. My rationale was to not say anything until I become the best at it. Some things are better kept quiet until you accomplish it.

When people saw you on New York Undercover, did anything change for you personally?

The main thing people wanted to know was how I got on the show. To them it seemed like I just walked in and was given that opportunity. They didn’t know I was actively pursuing a career in acting, but I was always an artist. I’ve been blessed by the grace of God with a drive, and it’s a blend of my mother and my father, which is when I want it, I don’t really care too much what other people think. So in the hood—I grew up in East Flatbush, as well as Crown Heights—the people saw it, and it was like, “Keep going.”

The recognition never tilted me off my axis. I can really say that I was never doing it for the fame. I really was passionate and committed to my craft. I was studying [Paul] Newman, Strasberg, learning the methods, the new techniques, and figuring out how to really apply them.I wanted to see what was going to happen, and how my commitment to craft was going to translate. This was when I [got the role as Marlo Stanfield] on The Wire. Now I’m on set, applying everything that I learned. Then the fruits of the labor showed in my work. My passion for acting never was for the fame, it was really for the creativity. But as you get older you realize this is about more than just talent; it’s also a business.

At first it just started [with me] reading a lot of books—Think and Grow Rich by Napoleon Hill, The Celestine Prophecy by James Redfield, The Spook Who Sat by the Door by Sam Greenlee—and I realized that money plays a big part in everything we do but you can’t allow it to stop you just because you don’t have it. You figure it out.

But also, a little after I started on The Wire, I would come back to Brooklyn, just coming through, and I would mentor. This young cat says to me one day, “Yo, Jamie, that’s how you do it? You just leave, and you never come back?” I said, “Pause.” Left. Called my manager, and was like, “Get all of my paperwork together that’s required to have a 501(c)(3),” because there needs to be more. That’s how Moving Mountains got started.

A bigger role and just shaping lives, and helping others realize they’ve got the gift of God in terms of talent. Moving Mountains is about kicking down doors, develop skills, talents, and abilities, while building character. I just don’t want to help anybody get the bag that’s going to throw it away. In addition to helping kids develop the talent and skills that they have, we want to make sure that they value that talent, and use it to give back. So, once a kid gets that bag—100 million, 200 million, 300 million—they’re not just wasting it, because they have that character.

From where you started at Tomorrow’s Future to now now with this new show, Bosch, what would you say about the art of acting?

I’ve got so much more to do. That arc right there is exactly where I want it to be in terms of planning, in terms of working, in terms of moving, working with great people, with great material on great networks. And then, transitioning eventually to amazing film, so it’s exactly where I want it to be, especially to be able to play a character, like Jerry Edgar right now with a moral compass.

The character that I played that everybody knows me for, from The Wire—Marlo—some might call him a sociopath, a drug dealer, a murderer but the dude was who he was. He was that dude on the block who was praised but he was also doing damage. Now, as Jerry Edgar, I’m playing someone on the other side of the game and I love the storytelling, as well as the range.

The first episode of Bosch’s fourth season aired April 13th on Amazon Prime.

You might also like