Cornelius Minor: Literacy for Democracy

Cornelius Minor thinks that the fuel behind inequality in the U.S. isn’t just the people making the decisions. It’s the systems set in place to keep people divided, immobile, and illiterate. So, what exactly does a modern hero look like?

First off, how long have you been in New York?

Over 30 years!

Could you tell us a bit about your family and their experience emigrating from Liberia?

Oh my gosh, my family is amazing. My parents are quintessential African parents who totally fit the immigrant parent stereotype. I have a younger sister, but you’d assume she was older because she’s very put together and oozes leadership. She works at the University of Georgia and has a Ph.D. in education, specifically studying schools as organizations and how people of color move across social and academic landscapes. Often times people drop out of school because they don’t feel like they have a place.

Our parents were super involved from the minute they got to this country. We left Liberia because of the Civil War, but the politics here were also very bad. I remember going to rallies for immigration rights with my dad in D.C. when I was kid.

One of the best gifts that my dad gave me is that he was always good in the streets. People from any neighborhood or any block knew him because he had done something kind like paid someone’s MetroCard fare. He used to know all the homeless people by their first names. My parents were undocumented for a while, but they were always agents being active and helping other people.

How do you elevate the concept of literacy to reach kids from underserved communities?

I still don’t consider myself a great teacher, but I’m better than anyone in Brooklyn at getting kids addicted to books. Every kid I’ve met has become a reader. So many kids say they hate reading, but I’m like, “You love spaceships? Look at all these spaceship books.” In many ways, I became a book dealer. People would come to me and be like, “Yo, I need a book. Yo, you got that new book?” And I’d be like, “Ya, I got it, I got it.”

Cornelius Minor

I don’t assign books as part of a strict, traditional curriculum; instead, there might be thirty-four different books assigned at once. For example, I’d put together a stack of twelve books, and that would be Olivia’s curriculum. And then I’d go to the kid sitting next to her, and that kid loves space, so I’d put together a different set of books for her. Everyone has their own individual curriculum based on them, and each student can apply the strategies that I’m teaching in their books. Kids loved it.

I had this kid who really wanted to be a rapper, so I got him poetry, biographies, and oral histories of hip-hop artists, and he studied his way into becoming a rapper.

I was able to meet him where his dream was.

So, how did your work educating community leaders and teachers come about?

One of the most influential educators I’ve had in my life was my mentor, Kathleen Tolan. She would introduce me to new books, help me change the tone of my voice so people would listen, teach me how to position my body so I wasn’t intimidating, and so on. One day I asked her, “How do I become you?” She responded by inviting me to teach with her for the day at Columbia University. She said, “I’m going to put you in a room with other teachers and see what you do.” She ended up hiring me on the spot, and I ended up working with her for seven years until she passed away. These days I often find myself thinking, “What would Kathleen do or say right now?”

I treat educators a lot like I teach kids. It would be criminal for teachers to hand students, especially those coming from trauma, a textbook curriculum. If kids have little or no support at home and you add academic trauma into the mix, it’s horrible. Teachers should be utilizing their individuality and passions to reach their kids. I can help them build a curriculum that accentuates all of the best parts of them.

I was working with this teacher who was having a tough time with her kids, and I found out she’s a circus performer on the side. In the circus, you have to know about physics, trust, humor, and your body. I told her, “Those books need to be in your classroom, and you need to teach with them because that’s who you are.”

What was it that inspired you to work with community leaders?

The most defining moment of my career was when Mike Brown was murdered in Ferguson, because he’s a kid that I would have taught. I remember thinking, “That’s my student.” I’ve taught tons of kids like him who are brilliant but defiant, loving and sensitive but may be distracted. How can we live in a world where that happens and there are no repercussions?

I remember being stuck and wondering, “How I can talk to my black and white students about what happened?” It reconfigured my thinking. A lot of my colleagues didn’t understand why it was so important and why it was connected to teaching. Our work isn’t just teaching nouns and adjectives, but it’s ensuring that students have powerful lives and that they’re understood. Writing gives you the ability to communicate in a way that is understood. I can give people pedagogical tools to change the situations we live in.

Soon I’ll actually be working with the city council in a school district outside of Indianapolis. They’ve had some high profile racial tension with their kids. The issue is bigger than the school; it starts with the businesses and political leaders. I’ll work with them on making the town a more equitable place.

The journey started in a classroom, then it became working with teachers all over New York, and then all over the world, and now city governments and municipal groups.

How can literacy help people navigate today’s political climate?

I want people back in that place of thinking critically and not just following leaders blindly, I want people engaged in civil discourse, and I want people being empathetic towards others. All of these skills live in reading and writing.

A king can’t tell us what to do if we’re literate.

A lot of people think today’s issues are fueled by personality (as in, he’s mean or she’s bad), but it’s not. It’s systemic. There are rules and practices set in place that marginalize and take advantage of others. Sexism exists because of structures in society that advantage men over women. I care a lot about destroying the systems that deny rights to gay people or marginalize my daughters because they’re women. In many ways, this Trump regime represents people holding tight to the systems that promote them and no one else. When we talk about an issue like racism, we’re not talking about kindness. It’s important to ask ourselves, “Are we still engaging actively in a system that supports racism?”

You disable a revolution when you keep people separated.

We’re in a place where collective study can save us. Movements are splintered because people don’t understand each other. We have rights for women, but they’re not inclusive of women of color. As long as the rhetoric keeps us divided, then nothing big happens. I’m thinking about how I can create more intersectional moments.

You’ve mentioned in the past that the current political climate in the US is mirroring the political climate your family left behind in Liberia. Can you tell us about that?

Liberia and Ethiopia were the only countries in the continent that were never colonized by European powers. It was idealistic. But the reality was, the country was ruled by wealthy people that didn’t consider the needs of the indigenous people who were not wealthy.

Even though everyone was brown, there were two races. My dad’s side of the family is Americo-Liberian and my mom’s side is indigenous. The Americo-Liberians are people who can be traced back in history to slavery in the US. My great-great-grandfather was one of the freed slaves who left the U.S. because he was unsafe as a literate black man. Liberia was founded by freed slaves like him, but many Americo-Liberians who came over brought some of the oppressive ways with them. They built structures that kept indigenous people out of rule. This led to a revolution in 1982.

When a rose doesn’t grow, you don’t blame the rose; you fix the soil around it.

Trump’s election impacted me profoundly. I remember having a conversation with my dad and he told me, “This is bothering you because you’ve seen a democracy fall before. In many ways, you’re built for this political moment. A lot of Americans who have not experienced that don’t know what to do right now. I think you know what to do because it’s in your DNA. This is why you exist in this historical moment.” I think a lot about what I could have done for Liberia if I was old enough at that moment, but I’m old enough now to be active for America.

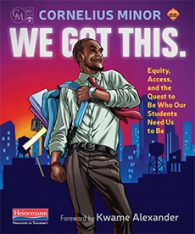

Tell us a little bit about your book.

My book, We Got This, is about listening to kids. When a kid says to you, “I want to be an astronaut,” listen and put an astronaut book in front of them. If they say, “My neighborhood is dangerous and I want to be safe,” find books that will help them learn how to be safe. Listening to people is the democratic process that America was built on.

We Got This wouldn’t exist without The Yard. Having The Yard not just as a place to work but a community of creatives has been a godsend. Plus, the managers, Cleo and Nikki, were incredible mentors to me. In many ways, they made it possible for me to get this book done. In a world where everyone is so busy, I don’t think we take the time to think about how valuable people like Cleo and Nikki are to our communities.

Cornelius will be hosting his book launch party at The Yard: Gowanus on November 13th. His collaborator, local comic book artist Jamal Igle, will also be at the party giving away one of his books.

You might also like