Photodom NYC and Brooklyn’s Black photography revolution

Tucked away on the third floor of an artist loft building on Broadway between Bed-Stuy and Bushwick, on any given day, you will find photographer Dominick Lewis. The founder of Photodom NYC, a shop he opened in September, oversees a cozy studio space filled with analog gear, photo gadgets, branded apparel, a mountain of packaged film, and nostalgic vintage cameras with a starting price of $65.

The idea behind the shop, says Lewis, is to create a safe haven for Black photography lovers from all over the borough and beyond.

“It’s pinnacle to have a space such as this that accepts and welcomes people who look like me,” says Lewis, whose passion animates him as he discusses Photodom and his love for photography.

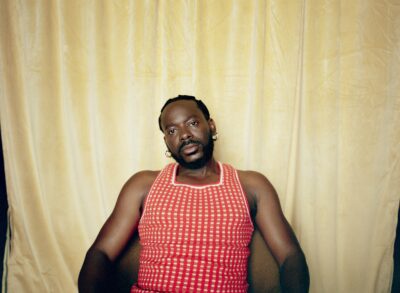

(Photo by Chris Cook)

Lewis, 26, says he began gravitating toward pre-digital equipment after high school.

“I appreciate the craftsmanship of the older cameras,” he says, with favorites including Nikon and Minolta. “There’s something special about a fully mechanical camera that doesn’t require batteries or anything like that to function.”

Lewis isn’t alone. He says he’s seen a surge in interest around film photography during the pandemic as more people look for an outlet in order to cope.

“Photography can be used as a tool for controlling the narrative,” says Lewis. “It’s important to see images that are reflective of your community and people who look like us especially for historical purposes.”

There has been a palpable uptick of work produced by Black creators since the beginning of the initial lockdown earlier this year. See in Black, for example, is a new collective of Black photographers with the stated mission of raising funds “funds to support causes that align with our vision of Black prosperity,” according to their website.

Collectives like See in Black and artisans like Lewis aim to create work that reflects how the marginalized experience the world.

“I’ve been following Dom via social media for years,” says Jeary Payne, a Brooklyn-based photographer and staff educator at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. “To see the idea he had become tangible is dope and affirming.”

Lewis (photo by Matthew Dalton)

The coronavirus, which disproportionately affects the Black community, happens to have ripped through New York in a year that was also marked with a spike in highly visible instances of police brutality. In the midst of this compounded chaos, Lewis continues to seek out pockets of joy and inspiration.

“I like to people-watch,” said Lewis. “I think there is a lot of uniqueness in Brooklyn compared to some of the other boroughs.”

And his impact is already being felt on the small scale: Dee Williams, a Black photographer and former Brooklynite, says Photodom NYC is the first black-owed photo store she has ever been to.

“It’s been a blessing to support and buy from a space that doesn’t see me or my art as an outsider,” said Williams.

The store itself is a refuge for the people Lewis is hoping to appeal to. History has proven that the Black dollar is valuable—Black Americans spend upwards of $1.4 trillion annually, according to the Selig Center for Economic Growth—and as the Black community leans into its support of Black-owned businesses, Photodom NYC is poised to thrive.

Much more than a gadget shop, it is becoming something of a hub: Lewis is using the store as a platform to hand out grants to local photographers and showcase their work, offer internships, and host neighborhood clean-up initiatives.

“I just hope to inspire people,” he says. “I plan to continue to educate and create spaces for photographers as well as grow and expand the store through community outreach and support.”

Or, as Met educator Jeary Payne puts it, “There is something about sharing a place and experience that is for us by us.”

You might also like