"Sunset in Cherry County, Nebraska" by diana_robinson is licensed with CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

No sleep til … Brainard?

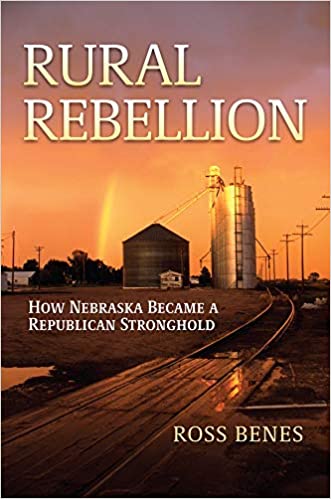

Brooklyn-based writer Ross Benes goes back to his Nebraska roots to trace the origins of our country's deep political rift

After low population states helped put Donald Trump into office in 2016, the urban-rural divide overtook the conversation. These developments led Brooklyn resident Ross Benes to travel back to his hometown in rural Nebraska to report on the forces that pulled the region where he came from rightward. The rifts that have made our politics unbearable today, culminating in last week’s attack on the U.S. Capitol by self-styled “patriots,” actually took hold in rural America many years ago.

The following is adapted from his new book Rural Rebellion: How Nebraska Became a Republican Stronghold.

When I think about my hometown Brainard, Nebraska, I like to recall all those summer days I spent with friends while my parents worked. Before I started fixing air conditioners each summer with my dad in sixth grade, I spent most of my summertime however I pleased. My older brother was supposed to keep an eye on me, but he didn’t give a damn if I went to the pool all day by myself, started a pickup basketball game, or played video games with our neighbors. He had his interests and I had mine, and we were allowed to go our own way just as long as we eventually came home, which is how we liked it. In Brainard, you don’t have to lock your doors, there’s next to no traffic, and most people feel a sense of comfort from knowing everyone else in town. The unsupervised freedom I experienced as a child is at odds with what I see when I walk my dogs in Brooklyn, where I witness parents helicoptering over their children and pets-who-substitute-as-children, as they shuffle them from one activity to the next.

When I think about my hometown Brainard, Nebraska, I like to recall all those summer days I spent with friends while my parents worked. Before I started fixing air conditioners each summer with my dad in sixth grade, I spent most of my summertime however I pleased. My older brother was supposed to keep an eye on me, but he didn’t give a damn if I went to the pool all day by myself, started a pickup basketball game, or played video games with our neighbors. He had his interests and I had mine, and we were allowed to go our own way just as long as we eventually came home, which is how we liked it. In Brainard, you don’t have to lock your doors, there’s next to no traffic, and most people feel a sense of comfort from knowing everyone else in town. The unsupervised freedom I experienced as a child is at odds with what I see when I walk my dogs in Brooklyn, where I witness parents helicoptering over their children and pets-who-substitute-as-children, as they shuffle them from one activity to the next.

I felt so free in the streets of Brainard that I didn’t fully realize how isolated we were. I was lucky to have a good group of friends who I played sports and created home movies with, which kept me busy. Others find small-town life to be suffocating. People get bored and drinking becomes a way of life. Some feel judged for their otherness and can’t wait to leave. Accessing mental health services becomes more difficult the farther you live from a city, which is a huge problem given that the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention found that suicide is most common in rural areas.

When I was roaming Brainard’s wide streets, I didn’t recognize that politically divisive issues were taking hold in rural America. The perception that rural residents have of being separated from the rest of the country has become a source of power for politicians. In small towns, where there are few social clubs and traditionalism is revered, it’s common for people to turn to their church for a sense of purpose and community. The church taught me to respect life and instructed me to live selflessly, but it also politicized abortion to the point that many voters only care about that one issue. This leads people in Brainard to vote for pro-life candidates who offer them nothing else but moral outrage.

When the town that you spend all your time in is full of white people and has no immigrants, you begin to view undocumented laborers as law-breaking deviants who worsen our nation. In this context, building a wall along the Mexican border doesn’t seem so asinine. Like many midwesterners, I was taught that living modestly and self-reliance were virtues. And because I was always one degree away from knowing anyone I had a personal interaction with, I was unfamiliar with anonymity. An appreciation for fiscal constraint combined with distrust of the outside world led me to oppose big government. Politicians have leveraged this sentiment to target public institutions and lower taxes for their wealthy backers.

Since leaving Brainard, each time I move I land in an even bigger city. Along the progression from Brainard to Lincoln to Detroit to Brooklyn, I’ve come to see things differently. When you see single moms without much community support struggling to hold everything together and when you befriend people who openly support abortion rights, it becomes harder to demonize pro-choicers; I now see gray in areas where I used to see only black and white. When you establish personal relationships with immigrants, they become much more than distant law breakers, and you realize that their humanity is every bit as valid as your own. When you develop chronic illnesses and find yourself spending an inordinate amount of time navigating through various states’ health exchanges on a low budget, you wish like hell the government could step in and make it easier. My perceptions wouldn’t be what they are if I stayed in my hometown and neglected metropolises.

You might also like