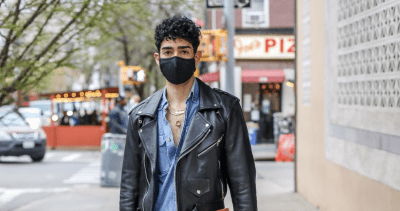

Cey Adams (Photo by Robert Bredvad, illustration by Johansen Peralta)

‘It was just such a wonderful time’: Artist Cey Adams and the visual language of hip-hop

A conversation with the graphic designer most responsible for the look of hip-hop in the late '80s and '90s

Like what you’re hearing? Subscribe to us at iTunes, check us out on Spotify and hear us on Google, Amazon, Stitcher and TuneIn. This is our RSS feed. Tell a friend!

It is no hyperbole to say that if anyone had a leading role in defining the visual culture of hip-hop it was Cey Adams. The early days of Run-D.M.C.? Cey Adams was there. The Beastie Boys, LL Cool J, Slick Rick? Cey Adams designed some of their most iconic album covers. Public Enemy, Biggie, DMX, Jay-Z? Them too. Usher, Mary J. Blige? Cey Adams was there.

Born and raised in New York City and currently based in Brooklyn, Adams emerged from the vibrant graffiti scene of the 1970s while still in his teens, tagging “Cey City” on subway cars and painting murals — and was one of the first wave of street artists to obtain gallery representation. He met the Beastie Boys before they were the Beastie Boys, and designed their first logo, t-shirts and singles. He linked up with Russell Simmons at Rush Artist Management where he designed logos and merch for an artist roster that included Run-D.M.C., Big Daddy Kane, Kurtis Blow, Whodini. When Simmons and Rick Rubin launched a little label called Def Jam Records, he joined on as creative director. If there’s an album from hip-hop’s golden era that you love, it probably has Adams’ fingerprints all over it.

“It’s not lost on me that it all comes out of New York, and I don’t say that as a slight to anybody on the West Coast,” says Adams, who is this week’s guest on “Brooklyn Magazine: The Podcast.” “I’m just talking about my journey and the journey of the folks that I worked with in New York at that time: Tribe Called Quest, Rock and Roll Hall of Fame inductees 2024. Mary J. Blige, Rock and Roll Hall of Fame Inductee 2024. It’s a big, big deal that we are getting these kinds of acknowledgments now because they put in the work, and it’s only right that people acknowledge the pioneers that paved the way for everybody else that’s making this music and having a lot of success.”

Adams — who has also worked with iconic brands like Mattel, Pabst Blue Ribbon, Apple, Google and Levi’s among others — joins us to discuss his career. We spoke the day after the opening reception of his latest exhibit, “Cey Adams: Silkscreen Prints and Multiples,” currently on view at MASS MoCA’s Gary Lichtenstein Editions gallery through June 14.

A retrospective of his career called “Departure: 40 Years of Art & Design” debuted in 2022 at Stone Gallery at Boston University. It is currently on view at the College of Visual Arts & Design Gallery at the University of North Texas, Denton. The exhibition will continue to travel in 2024 and beyond.

The following is a transcript of our conversation, which airs as an episode of “Brooklyn Magazine: The Podcast,” edited for clarity. Listen in the player above or wherever you get your podcasts.

You opened a show at MASS MoCA in North Adams Massachusetts yesterday, two days ago. Silkscreen Prints and Multiples with Gary Lichtenstein. Tell us about this show.

So I took the drive from Brooklyn to MASS MoCA and it was my first time going there and it was an oasis. Beautiful campus and they got nothing but real estate. One of the things that I was excited about was they have this amazing wall drawing retrospective of Sol LeWitt, who’s one of my favorite artists. What I was there to do was to celebrate a series of works and prints that I made with Gary Lichtenstein Editions from 2016 to 2023. We met in 2016 and we’ve been fast friends and collaborators ever since. Gary is a master. He’s one of my favorite artists and collaborators and he worked with so many of my pop idols and he’s just a really talented guy. He’s funny, great to be around and I learned so much about silkscreen printing from Gary.

That’s amazing: you’re still learning stuff. Is this collage work or what is the work?

What I do is collage. What Gary does is silkscreen printing and we come together from time to time. It’s like being in a band and you go off and you do solo projects and then you come together and you make a record and then you go off and you do solo projects. And so that’s the way it is. Gary’s doing his thing at Gary Lichtenstein Editions. I’m doing my thing as a visual artist and then we come together to make prints for various projects that I’m working on or things that he’s working on and then we go away and then we come back together again. I was excited to be the first show and it’s just wonderful to see all of these prints that we made together over the years and time goes by very quickly, especially as you get older.

And speaking of time and time going quickly, this is where you’re at now. Let’s go back to the beginning. I’ve heard you say you don’t really have a memory that predates your being obsessed with art, design, creating. Where do you think this comes from? Would you say it’s a compulsion almost?

I don’t even know why it’s necessary to even try to pin it down. When you are a maker or an artist, it’s literally just there. I tell people sometimes it’s like the limbs on your body. Do you ever think, “Oh, man, when did my arms and legs start working?” It’s just a part of you and they do and art is that way for me. It’s just always been there. And as you get older, it’s harder and harder to remember certain things, but when it comes to the early days, those things are crystal clear and making art is one of those things that’s just very clear for me. It’s just always been there like body parts.

You’re wearing a T-shirt with the Batman logo on it right now. You’re a logo designer. Do you remember the first designs that you were obsessed with? I’m thinking cartoons, Mad Magazines, cereal boxes.

All of the above. Anybody else of a certain age, you are interacting with these things that are just in front of you and we are born in the age of television and Saturday morning cartoons are there. I recently started working with the folks at Mattel and it’s like a dream come true, because oftentimes as an adult, you don’t get to interact with your past. And for me, it was really wonderful to have something that I loved as a kid come back around full circle as an adult and for them to say, “Hey, we love what you’re doing. Let’s play.” And there’s no, “Let’s play in this way or that way.” It’s like you get to design how you’re going to play and they’re going to support you.

I’ve seen the Barbie logo that you did, or remixed. Hot Wheels as well. What are you doing with Mattel?

Anything I want to. That’s the point. I have to say it in that way because it’s just there’s so many artists out there and there’s so many people that have to sign off on when things happen. So when you get a call about collaborating with a brand that you’ve loved almost your whole life, that’s a really great thing. To me, it’s just pure heaven to get to work with a brand like that. And for them to give you the space to just say, “Okay, I want to do this or that, this or that,” it’s just like, “Wow, thank goodness. Hot Wheels was something that I loved,” and I was already working on before I had the official green light. And so we just made some really cool stuff and it’s just so much fun to have somebody see you and understand what you do instead of you having to sell them on what you do.

Did you see the “Barbie” movie?

Not only did I see it, they invited me to the premiere in Hollywood and I got to experience it as close as possible and it was just amazing. I got to catch up with some of my old friends that are a part of the film and it’s just great.

Is this part of your Trusted Brands line of work where you’re looking at these iconic American brands through your own lens and you love exploring those brand identities?

The idea is very simple. I’ll keep it in hip-hop terms for the purpose of time and clarity. My idea was I just wanted to remix some of my favorite logos of the past. And when I say remix, I don’t necessarily mean change, just reinterpret it from a visual perspective, but also to show love to a lot of these brands that I cared about as a kid growing up and almost do a, “What if I was designing it?” but at the same time, if you were the designer and you looked at one of my works and you were experiencing it in person, I would hope that you would say, “Wow, there’s not a line that’s out of place,” and it’s purely for the love of graphic design and pop art and just trying to make something that pleases me first and hopefully somebody else second.

This is really through the line through your whole career. You started as a graffiti artist. Graffiti was everywhere, but when did you first become aware of graffiti in the ’70s?

I would imagine just walking around with my parents and things when we’re running errands or taking me to school or something, I would just see tags on the train and on walls and things. I’m from the city, so it’s not like I had a lot of different outlets to focus my creativity on and so everything is right in front of you. And so when you see things on the train, it just gets your attention because I’m already excited about anything that’s colorful, anything that has a bold message. And so when I see these giant trains, it’s just one of those things that instantly makes me think, “Oh, this is something that I could do,” even if I didn’t know how to do it at the time.

From the get go, you were like, “This is something I can do. I want in on this”?

It had all of the ingredients that young people love, the rebelliousness. It’s got color. It’s big. It’s got all kinds of challenges built into the art form. And so for me, that was perfect for where I was at that time in my life. I wanted to experience all of it.

A young Cey Adams in ‘Style Wars’

I re-watched “Style Wars” last night, the iconic documentary from, what, 1982? I have a 15-year-old. She watched some of it with me and she’s like, “Oh, yeah, kids still do that. They go down in the tunnels. All the boys in my class climb up the bridges and stuff.” They’re not tagging, but they’re still doing the dangerous outlaw stuff.

Yeah, they’re probably worse than we were at the time. Who knows? I’ve outgrown the feeling and urge to do all of that stuff, but I still admire that it’s intoxicating for young kids.

For sure. There was a scene in that you’re very young and there you are, you’ve got your little Cey sweatshirt. You’re at the Graffiti Above Ground gallery show and I don’t know how old you are, maybe 19?

A teenager. Yeah.

The quote from you is, “I’m into making money.”

You have to understand that, at that age, that was what it was about because we didn’t come from a lot of means. And so any opportunity to create a mural and make a few bucks or to sell a painting or paint a jean jacket, whatever it is. All of those things were welcomed at the time. And I wasn’t shy about mentioning it because I did not know that they were making a film that was going to be so important, but the reality is I don’t know that I would’ve done anything different except maybe speak a little more clearly into the camera, but that was something that teenagers do. We’re a little wary of it, but then at the same time, you’re drawn to the attention all the same.

So graffiti then was a canvas for you to express yourself where you didn’t necessarily have one to get noticed. It was also an opportunity, a ticket out.

All of it, yeah. That’s why I say it’s about changing your circumstances. And if your artistic ability is going to help to change that, that is what it is about. It’s the same thing as an athlete from the hood. The whole goal is to do something with the gift. If you’re not doing that, then it might as well be handed off to somebody that can appreciate it a little bit more.

You certainly had a lot whole lifetime of being in the right place at the right time and with the right talents. Talk about Joyce Tobin, that was her gallery, right, the gallery that represented you?

Yeah. I’m 18, 19, 20 at the time. Joyce is maybe double that, so she might’ve been late 30s or 40. And her and her partner Mel Neulander had a gallery called Graffiti Productions, Inc. and we used to call it GPI for short, but it also had another name Graffiti Above Ground. It’s interesting that all of these other organizations like Beyond the Streets and Beyond Walls and all of these Beyond companies, they were one of the first. And Graffiti Above Ground says it all. And so they gave me my first opportunity to sell my work in a gallery setting and a lot of other folks got their first opportunities there as well. Between GPI and The Fun Gallery and SE Studios and Noga and a couple of other places, those were the starting point from which everything blossomed from. And whether it was in the ’70s or the ’80s, that was the beginning of having the potential to go mainstream.

What kind of impression did she make on you at first? You’re talking about a white lady in her middle 30s maybe. Did you see it as, obviously, an opportunity. Potentially exploitative? Like, “I want to cash grab on this underground thing”? Were you ever wary of her motives?

No. If I was, I wouldn’t have been there. I would’ve just stayed home. That’s the thing is, if you’re distrusting, you don’t have to be there. It’s not like they’re looking for you, you’re looking for them. For me, it was just opportunity to learn, to find an entry point to learn about the art world, because prior to that, just visiting museums is not going to teach you anything unless you are reading about who your art heroes are. And for a kid to get an opportunity to work with somebody in a professional gallery setting is really difficult. Who wants to take on that responsibility? If you give a kid $200, you’re never going to see them again. At that time, that was a lot of money. Joyce gave us the opportunity to showcase our work in a gallery setting, like I said, and also just placing a bet on what we were doing was really important, because for the most part, people didn’t really understand what graffiti art was and because we were young, we were labeled vandals, outlaws, all of the things that the art form comes along with. We still haven’t really broke that stigma about the potential of what graffiti can be. For every person that loves it, there’s still somebody that hates it, and for every person that’s transitioned into a fine art career, there’s still plenty of graffiti vandals out there that are starting right back from where we were in the ’70s. So it’s like the art form has evolved and not all at the same time.

Some of your tags are still out there, right? I think there’s one in Greenwich Village up on a wall that you can still see from back in the day.

Very faint, but it’s still there. I checked last week.

You would go on to study painting at the School of Visual Arts. You’re the same age and friends with people like Jean-Michel Basquiat and Keith Haring. You meet Andy Warhol through them. What was that period like, the schooling? Was that for connections or was it to learn the craft, a little bit of both?

The thing that I took away from all that was it was an alternative to being in the neighborhood. It was really about trying to build something out of nothing and I have always known that. I think that just having the opportunity to be around Andy, he was a professional artist at that time.

Did he loom large in your imagination?

Of course, sure. It’s like, if you’re a kid starting to make music and you’re hanging out with Michael Jackson, if you love the craft, there’s no mistaking who he is. He was attracted to it in the same way. It’s energetic to always be around young people. It’s why people do it. That energy is intoxicating. And so to be around somebody that I looked up to was amazing. I don’t know how he perceived what it was like to be around him, but I certainly thought it was great. And by comparison, I have young people that feel that way about me today and I don’t take myself any more seriously than I did when I was a teenager in that way. When I’m around somebody that wants to learn something, if I can teach them, I will. But I don’t treat it as though it’s such a special moment for them. They’re young, they might be excited one minute, next minute they’re running off to do something with their friends. In the end, that’s what it is.

Did Andy teach you anything or did you learn anything from him?

Sure, but it’s more what he represented than what he said. He was a man of very few words, as you probably know. And for me, it was just having the opportunity to rub elbows with somebody that I was only in contact with through museums, and then all of a sudden, we’re hanging out and going to dinner at Mr. Chow’s and all the rest of it. It was great. It was absolutely wonderful.

Talk about the loss of that generation, neither Basquiat nor Haring got to live full lives. I wonder how many Basquiats and Herrings are out there that never got famous that you knew.

A lot. They had something very special. I was telling someone this the other day, of all of the people that I hung out with in the ’70s and the ’80s, there’s only a handful that “made it” and I think that those are the people that have the drive and the determination to overcome all the obstacles. And I can think of about five people that cracked the code that came from that school and it took us a lifetime of learning it and pushing it, just pursuing a love of artmaking to get here. And if you are lucky enough to be one of those, then you can tell the story of what that journey was like.

It’s come up already in this conversation a few times, but just in studying your career, it’s about adaptability. You’ve been able to adapt to your circumstances, recognize an opportunity and be game.

It’s pretty easy when you start out that young. You learn from your mistakes and the best thing about being young is that you are young and you have time to make mistakes and learn from those mistakes. Hopefully, meet people that will support what you’re doing, so you have the luxury of doing it for a very long time, and then hopefully, giving an opportunity to other young people or teaching young people about what your journey was like, so they don’t necessarily make the same mistakes that you made. That’s the benefit of surviving. That’s the benefit of being on a journey like that. You don’t have to get them to love the people that you loved when you were growing up as long as they appreciate the opportunity to take away something that hopefully will help them develop in their own careers.

So around this time, speaking of opportunities, you began working with Russell Simmons’ Rush Artist Management. What was the mandate? You’re out there creating logos, tour merch, billboards for artists like Beastie Boys, Run-D.M.C., De La Soul, EPMD, Slick Rick, Big Daddy Kane, LL Cool J. The list is epic. What was that chapter?

It was great, but looking back, what really made it great was that we were all young and we were all doing it together. Some of those artists I hadn’t seen in forever. Just recently, I was out in L.A. at a 40th anniversary gala for City of Hope and my friend Lyor Cohen. Lyor was the manager at Rush Artist Management. Rick [Rubin] and Russell were Def Jam. Russell was Rush and Lyor was the manager at Rush Artist Management. Prior to that, he was Run-D.M.C.’s road manager.

That’s right. Oh, right.

So Lyor’s been in the game a very long time and now he’s an executive at YouTube Music Worldwide, but he was being honored by City of Hope, celebrating his 40th anniversary in the show business and the 50th anniversary of hip-hop. In attendance at this gala, we’ll just go down the line, it’s myself, Jay-Z, Diddy, Ludacris, Jermaine Dupri. Master P was there. Who else was there? Big Daddy Kane is there. Ja Rule is there. Run-D.M.C.’s there. EPMD, Slick Rick, Kurtis Blow, LL Cool J, Public Enemy. It just went on and on and on and I’m going to forget so many people. Dru Hill, Sisqo. It was just the whole roster.

Yeah, I heard you talk about running into Redman there as well.

Redman is there. All of them, but I have not seen Big Daddy Kane in years. I could say 20 years and be spot on. I guess I should take this opportunity to say RIP to his long-time DJ, Mister Cee, because I just met him recently a couple of weeks before he passed and we were talking about The Notorious B.I.G and our relationship to him. And the reason I mentioned Big Daddy Kane is because I think that a lot of artists, him in particular, these guys are sharper, if there’s even a way to say that, than when they were younger. His performance was fire.

I saw the Barclays Center a couple of years ago he destroyed.

Yeah, same thing with my buddy LL Cool J. He was doing this since he was a teenager and he lit that stage on fire. So much energy. That’s the beauty of seeing this over 40 years. You get to see some of your friends still doing that thing at the top of their game and it’s just such a great feeling to witness it and to be a part of it in person.

So the people that you’ve worked with, you can just go down the whole list. You mentioned a lot of them, LL Cool J, Notorious B.I.G., Public Enemy. These are people who defined global culture and you had a hand in that visually.

Certainly. It’s not lost on me that it all comes out of New York and I don’t say that as a slight to anybody on the West Coast. I’m just talking about my journey and the journey of the folks that I worked with in New York at that time: Tribe Called Quest, Rock and Roll hall of Fame inductees 2024. Mary J. Blige, Rock and Roll Hall of Fame Inductee 2024. It’s a big, big deal that we are getting these kinds of acknowledgments now because they put in the work and it’s only right that people acknowledge the pioneers that paved the way for everybody else that’s making this music and having a lot of success. And it’s just great when you get a chance to see your old friends and we’re all adults now and we know how to treat each other. And it’s just fun because everybody’s happy and there’s just no better feeling.

And when I left that gala, I was doing cartwheels. It was just so much fun and I can’t stop talking about it because I’m traveling so much, I don’t get to see people very often. And to chop it up with Jay was really great. He’s doing so many wonderful things now. Same thing about LL and Public Enemy and Ludacris. It’s just, “Wow.” It’s just really, really cool. And especially my buddy Jermaine Dupri, he’s got the charts, he owns Billboard. He’s got it on lockdown, and this is a guy who’s been doing this since it was in single digits almost. JD has been doing it big for a very long time. So big shout-outs to Jermaine Dupri.

You’re at Rush Management with Russell. You do the King of Rock tour, Run-D.M.C., their first big tour. You also meet Adam Horowitz around this time. How did you two link up?

We meet prior to that. I think I met The Beasties in 1981, something like that. We’ve been joined at the hip ever since and it’s really hard to talk about them without getting emotional because we all came up together and they were there for all of my successes and I know I certainly was there for all of their successes.

What were they like in those early days? I’ve certainly heard a lot of those stories about the clubs, you’re at Danceteria or whatever, they’re not fully formed as the Beastie Boys from day one.

This is the way I think about it. I did not have any expectations for what I wanted them to be. They were just my friends. The idea that they achieved what they achieved was unimaginable because that kind of success eludes a lot of people in show business and they just did the unthinkable. I just feel so fortunate that I was there to witness it firsthand and we are still friends to this very day. I just saw Adam and Mike a couple of weeks ago, and sadly, today is the anniversary of the passing of Adam Yauch and I miss him so much, but I feel so fortunate that I got to experience some of the best years of my life with those three guys and the rest of the crew. Run-D.M.C. as well because they were there right alongside them and we did so many great things together as individuals and as a collective. And I know that stuff is rare. I knew it when I was in my early 20s and we were on the “Licensed to Ill” tour and we were traveling around the country. And I knew it when we went to Europe and Asia. It just felt like a moment and we got to share all of that together. And I can’t even put it into words. It was just such a wonderful time.

When Simmons and Rick Rubin formed Def Jam, you’re basically the founding creative director. Of course, this is in the ‘80s. “Creative director” as a term didn’t exist. You were a graphic designer before it had a name.

The term did exist, but it wasn’t a household term, let’s just say that. I was very fortunate because my buddy Eric Hayes taught me a lot about graphic design. And when the opportunity to design album covers presented itself, I was lucky that I was in the right place and I had the chops. This is a great opportunity to always set the record straight and there were a lot of talented people around at that time and Eric was certainly one of the premier, but we went back to the graffiti days. And to be able to have a different career path was gigantic because people did not expect that much from a lot of us who did our work with spray cans.

There was no blueprint for your career.

No, none. There’s no blueprint, but that’s also a great thing because you get to design it in any way that you want and nobody’s going to tell you, “You can do it if you are strong enough in your conviction and you’re willing to work hard.” That’s what it was like being at Rush and then later being at Def Jam, is you had to work really, really hard and the opportunity was there because nobody was telling you no. If I was trying to be a rapper or a producer or a DJ, I would’ve had a lot of competition. But because I was interested in graphic design, there wasn’t a lot to talk about because nobody that was hanging out in the office cared a lot about that. Like I said, Eric had his independent studio and he was doing his thing and so I started my independent studio and it gave me an opportunity to really build the kind of career that I wanted for myself.

Was that the Drawing Board you’re referring to?

Yeah. My company was called Drawing Board Graphic Design. I had a partner named Steve Carr who I’m still friends with right now and we just did everything under the sun and we just had such a great time.

It was like an in-house design studio.

It was exactly that. It was an in-house design firm, but Def Jam was our biggest client. Bad Boy Records was our other biggest client and then we worked with all of the other labels in New York and L.A.

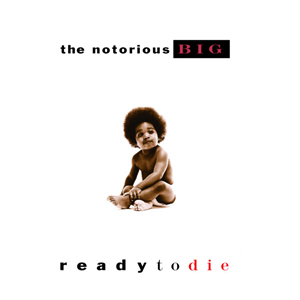

‘Ready to Die’ by the Notorious B.I.G. (Bad Boy Records)

Was that any tricky political jiu-jitsu, they didn’t care that you were doing “Ready to Die” for Biggie or anything?

This is small potatoes. The people that are selling millions of records, this was not a threat to them. I will say that, when other competitors were looming large on the charts, then I think people started to look at it. But again, what Steve and I had at the Drawing Board was very different than what the major labels were doing in their art departments. They didn’t have the same kind of soul that we had. So again, it wasn’t like we were competing with them.

You’re the art director, creative director for these album covers. You’re servicing a client. Was there ever any tension between what the client wants and your creative freedom?

Always, but you figure it out. At least, you didn’t have to compete for the job of doing the album cover. That all by itself was starting to happen once records started selling. So if you don’t have to compete for the job and your ideas and you just have to make sure that whatever you’re doing pleases the recording artists and management and the record label, that’s doable and that’s what we did. We always made sure that the artist was a part of the creative process.

And you were working so much, obviously, in the moment. You don’t know with any given project, “This thing’s going to become iconic and this thing is going to be forgotten,” you’re doing logos like Hot 97 or “Chappelle’s Show,” these things that have become iconic in and of themselves, but at the time, how many did you do that just no one saw?

The things that you just mentioned were after I left the Drawing Board, but the thing is you can’t spend any time thinking about that because you don’t have any control over it. We kept our heads down and we worked insane hours. There were times that we worked six, seven days a week and then you come back on Monday hopefully with a fresh battery and you do it all over again. This is the nature of how the business was in the late ’80s and even in the early ’90s. They didn’t put pressure on us in that way and I just knew early on that the recordings were what people were paying attention to. It was like they weren’t riding us like that. We had deadlines to get things out the door, but if you make the recording artists happy, everybody gets out of your way.

Well, it’s interesting that you say, “Once it’s out in the world, it’s not yours anymore.” Is that hard or it’s just the nature of the beast?

When I say that, I just mean that, one, you can’t change it until you do a second run, and then even then, sometimes you can’t change it, but it’s just not worth putting pressure on yourself. There’s so much coming behind it that you don’t even have time to think about those things. There’s no such thing as a failure. That’s up to the music. It’s not up to the art.

Do you mourn the loss of the tactile facet of music? I’m a record collector. I love holding the record.

Of course, of course. I buy things on Amazon and other online platforms that sell vinyl, but I don’t design anymore, so there’s nothing really to miss. I have a retrospective exhibition that’s traveling around the country called “Cey Adams, Departure: 40 Years of Art and Design.” And that exhibition has a massive installation survey of a lot of the album covers that we did at the Drawing Board. I get to see them whenever I’m in whatever museum it’s being exhibited at around the country and that’s a great thing just to be able to see some of this work with fresh eyes. And it’s just a lot of fun because I always get to hear about how much those album covers mean to other people and it’s just not lost on them, so it’s a wonderful feeling.

‘Hello Nasty’ by the Beastie Boys (Grand Royal)

Is there one or two that mean the most to you?

I don’t know about the most, but I think about the recording artists. For example. I’ve never designed an album cover for Run-D.M.C., but I’ve worked with them so long, I don’t feel like I’m missing anything. Beastie Boys are probably my all-time favorite because we spent so much time together and we just laughed so much. Same thing with Public Enemy. I spent a lot of years working with them. And I think, with those bands in particular, we had a really special connection because we spent so many years at Rush together. I think that we got an opportunity to really see each other as people and as individuals and we were young. There’s just no substitute for that. Man, I could just go on and on and on about how wonderful the time was with those artists.

That was fantastic answer. I was curious about specific album covers also.

I can tell you easily: “Hello Nasty” is one of my personal favorites because I got an opportunity to watch the guys record it and we sat down when we were having meals and we were talking about the album design. And we talked about different illustrators for the front and we would look at photographs and we would talk about it and we would laugh about it. We’d put an idea out and I’d do some sketches, and then day later, they write another song, and all of a sudden, the title of the record is different, the artwork is different. And the thing that I always enjoyed is that it’s their record. It’s not my record. It’s their record. And it’s important to get it right for them with them. And I never took it personal. That’s one of the things I love about that time, is that I always had that in mind front and center, “This is about them.”

‘Fear of a Black Planet’ by Public Enemy (Def Jam)

And the same thing with Public Enemy when we did “Fear of a Black Planet.” It’s Chuck D’s concept. I’m just bringing it to life. And that’s the job. It’s like I live behind the curtain and I’m there to help the recording artists. I was looking at, oh my goodness, like five different Redman album covers and they’re all lined up one after another and they all have some form of red in them. And they just look amazing together. It’s just this wonderful collective and it’s a theme that spreads through every record. And to be able to work with an artist that much is really wonderful and it’s not something that’s lost on me because it does not have to happen.

We had mentioned “Chappelle’s Show.” Can you talk about how that logo came about?

Dave is a really good buddy of mine and we’ve known each other for over 20 years now.

But was he a friend of yours at the time or is that how you met?

No, I didn’t know him. I think a buddy named Jordan Rubin who was friends with Dave and Neal Brennan. And Jordan introduced me to the two of them. We sat down and we talked about this logo and Dave just said, “I need you to do something hot.” He didn’t art direct me or micromanage what I was doing. I just wanted to create something that I felt was revolutionary because that’s what I thought about his comedy and this is a perfect example where you could say, “The rest is history.” He did the rest and I feel very fortunate to be connected in that way because I’ve worked with so many talented people that the world doesn’t know about.

I heard he brought you on stage in Madison Square Garden to thank you for the logo all these years later.

Not only thank me, he gave me a diamond pendant and put it around my neck on stage. So talk about an aha moment. Wow.

Talk about the pivot, if you will, into fine art. You moved out of that space. You are working with brands and that probably comes with its own challenges and opportunities, but you’re also doing fine art. It’s really a full circle moment. I come all the way back around to where I started as a teenager, but for me, it was an opportunity to make something that makes me happy first, and hopefully, if there’s a few people that enjoy it as well, mission accomplished. I try not to put any pressure on myself, but just making art is a gift all by itself and that’s the way I think about it. The work that I do is really about my love of graphic design. And so working in a collage format, I try to tell stories using paper and glue and magazines and newspapers and things and just trying to make a throughline from where I began to where I am right now and finding folks that enjoy it along the way. And I think I’ve been successful in that regard and it’s just a great feeling to have people supporting something that you love to do.

The ‘Chappelle’s Show’ logo

What’s next on your horizon? How do you stay inspired? How do you stay engaged?

First, I start by waking up. I was really fortunate to get to make this beautiful coffee table book and boxset called “The Smithsonian Anthology of Hip-Hop and Rap.” That was done with Folkways Recordings and the National Museum of African American History and Culture. And it’s a nine-CD boxset and a 300-page coffee table book and it basically tells the full story of hip-hop from The Sugarhill Gang to Drake and everybody in between. To get to art-direct and design a project like that for the museum is just the best. It’s the absolute best. There’s nobody micromanaging. I got to work with all of my friends again and really tell the story of our journey. And to be included in the package as a subject as well as the designer behind the scenes is a real full-circle moment because it was nice that they acknowledged the time that I put into my career and to allow me to be the one to spearhead this project was so much fun, even if we did have to weather the storm of the pandemic in order to do it.

I lived in DC 25 years ago. I volunteered with the archivist, a guy named Jeff Place and he was taking the old acetate recordings and putting them on CD and I would help him do that. I got to hear Mary Lou Williams on acetate recordings. It’s a really cool room to be in.

I spent a week a month there while we were working on this project. I sadly was not familiar with Folkways Recordings prior to that, but believe me, I’m well versed in Lead Belly, Woody Guthrie and everyone else that recorded with Folkways. It’s a great label.

Speaking of music, you were curious, you were omnivorous, you weren’t just hip-hop. You listened to Skynyrd and you hung out in the punk scene and you love Fleetwood Mac’s “Go Your Own Way.”

I’m in my 60s. Fleetwood Mac’s “Rumors” comes out in 1977 and that was my favorite record. I’ve seen Fleetwood Mac at least five times. I’m definitely a product of my environment. Those kinds of experiences are I think what informs the work that I make. People have a strange misconception that because you work in hip-hop, it’s the only thing that you know about, but they don’t take into consideration that hip-hop is 50 years old. What about the 12 years that I was around before hip-hop?

Plus it’s sample culture. It pulls from everywhere.

Yeah, exactly. And so why you can’t love Billy Joel because you love Slick Rick?

I like them both.

There you go.

Check out this episode of “Brooklyn Magazine: The Podcast” for more. Subscribe and listen wherever you get your podcasts.

You might also like