Photo illustration by Joelle McKenna

Bob Guccione Jr. isn’t done talking

The recidivist Spin publisher calls out Rolling Stone’s ‘prostitution,’ Larry Flynt's alleged hit on his dad, and why 99% of digital media sucks

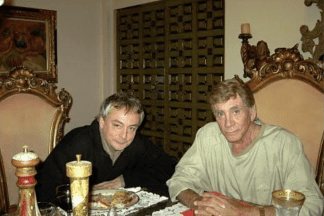

(Left to right) Gucciones Jr. and père

Bob Guccione Jr., whose publishing brainchildren include Spin, Gear and, most recently, WonderLust, was born in New York City in 1955 and was sent almost immediately into a transatlantic life, living in London from age two until his teens. As a child, he witnessed an old, conservative city wake up from post-war doldrums, and he saw a U.K. that was shedding its colonial skin. A generation of kids—British Baby Boomers—were suddenly free from mandatory military enlistment, and the nation instead was invading world culture with a rock ‘n’ roll brigade of Beatles, Stones and Kinks.

“It was fantastic, it was cool, because it was in the Swinging Sixties,” Guccione Jr. said, in his still-strong Cockney accent. “But I was still too young for that. While I didn’t participate, I knew it was going on.”

Guccione Jr. wasn’t too young to start thinking like a publisher, which was in his blood. His famous father, Brooklyn native Bob Guccione, launched the adult magazine Penthouse in London when Guccione fils was 10 years old. (Guccione Sr. also later published titles such as fashion magazine Viva and sci-fi journal Omni.)

At the age of 17, before permanently moving back to the states, Guccione Jr. edited and published a magazine called A Step By Step Guide To Kung Fu, becoming Britain’s youngest-ever publisher at the time. At 19, he became the youngest-ever U.S. publisher of a national publication with Rock Superstars, a mid-’70s magazine for music fans. Twelve years later, he founded Spin and turned the monthly magazine into an alternative-culture tour de force for Generation X, defining the 1980s and ‘90s with striking cover photos of Madonna, Sinead O’Connor, Public Enemy and Nirvana.

While he sold Spin in 1997, he was invited back last year for a hands-on advisory role by the publication’s new owners, Next Management Partners, which purchased it from Billboard-The Hollywood Reporter Media in early 2020. Since May ‘20, Guccione has worked with Spin CEO Jimmy Hutcheson and editor Daniel Kohn on reimagining Spin—which had been digital-only since printing its last magazine in 2012—as a digital destination that satisfies the media appetite for not only Gen X diehards but also younger generations of Instagrammers and TikTok devotees.

We caught up with Guccione Jr. to talk about the Spin reboot, his rivalry with Rolling Stone, the late Larry Flynt, his dad and Hef, and print’s glory days. The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

That 80’s Guccione Jr. (courtesy SXSW)

For an advisor, you seem to be in a highly participatory role at Spin.

I said to [Next Management Partners], I really want to get my hands in it. So, I’ve done everything from some editing of stories, to the assignment of stories, to writing things. I wanted to make sure I could make significant change and make a difference. And that doesn’t mean always changing things—sometimes, things are good to leave them alone. But I’m not just sitting here pontificating from a big chair, no.

Why does Spin need to exist in 2021?

I’m not in the “need” business. I’m in the “want” business. What I do is create things people want. Any publisher who comes to you and says the world needs a [publication] is, frankly, lying to you. Spin exists in 2021 in a way it didn’t frankly in 2019. Because in 2019, it didn’t give anybody a reason to really want it, which was I think why it was the runt of the litter [at] Billboard, and they let it go. Spin has always been interested in music that is new, not just because it is new, but because there was something interesting going on—here was a passion or an angst, or just an energy. Recently, we’ve been trumpeting a great new artist called UPSAHL. I don’t know if you’ve heard of her.

I’ve heard or read her name before.

Spin hadn’t been doing that for 10 years, just saying, “I like it. [She’s] in the game.” And so that kind of energy’s coming back.

Your old rival, Rolling Stone, is also bringing new energy to its brand but in a much different way. It recently unveiled a $2,000-per-year thought leadership platform on which basically anyone can contribute to for a fee.

Oh yeah. Such a heaping pile of steaming shit. When I heard it, I said, “Jann Wenner is turning in his grave, and he’s not even dead.” And that guy’s a genius, somebody I have 100 percent admiration for. But my God, how he must be in agony, looking at that fantastic legacy, being twisted so cynically. And it’s prostitution, pure and simple. Rolling Stone is saying, “We will sell our body.” That’s what they’re selling. And it has a price, and the price is right on the door: 2,000 bucks.

Over the years, what has that rivalry been like?

I always say, I never took a meal off [Jann’s] table. He never starved because of me. And it was a competition. He dissed all over me, too. We were fighting, we were neck and neck. And so that was all in good spirit. In fact, of course, I totally respected him, and Spin followed their lead. In our early days, we were for Generation X what they were for Baby Boomers. So, nothing but total respect.

Brooklyn is a part of your life story.

My dad was born in Flatbush, where his Sicilian family lived for years. And my girlfriend, Liza [Lentini], and I lived in Brooklyn Heights during the 2000s. But truthfully, I have always been a Manhattan guy.

Your early childhood was spent in London. What was that like?

So, in the ’60s, I was very conscious of the fact that post-war London was still a city being repaired and rebuilt. As kids, we played on bomb sites, which were literally just rubble. I found an unexploded bomb with my friends one day, dropped by the Germans during World War II. And we were jumping up and down, trying to pry it loose, until a policeman came over and very gently said, “Don’t do that, lads.”

What was it like growing up with a dad who was an adult magazine publisher?

I had no concept of it being controversial or provocative in any way until I was about 18, 19 years old, when I realized, “Oh, people are really either very stoked about this or very angry.” While I was always very proud of my dad, I was particularly proud then, because I knew he pissed off people. And that’s one of the things I certainly learned from him, is the importance of sticking to your guns even if you piss somebody off. Which in our social-media-obsessed, intimidated world is an anathema now. People are afraid to piss anyone off. Which I think is terrible because it means nobody actually goes far out on a limb and has a thoughtful opinion about anything for fear of inciting a mob against them.

Speaking of opinionated people, Hustler publisher Larry Flynt recently passed away, and, given your family’s magazine history, I was wondering: Did you know him at all?

No, I never did, and I never wanted to. I thought he was a wretched human being. Actually, the FBI came to my father’s house one time, and they said they wanted to talk to him and that I should leave the room. My father said, “No, my son can stay.” They said, “OK, but this is what we’ve got to tell you: We’ve uncovered a plot by Larry Flynt to have you assassinated.” He so hated my father, he apparently put out a hit on him. And [Flynt] was no defender of the First Amendment. All he wanted to do was defend his own right to put out his really, really disgusting magazines.

You’re saying Hustler was misogynistic compared to everything else.

Oh, beyond misogynistic. Misogynistic would have been an elevation. It was about degrading women. That was their product. Penthouse and Playboy were classy. They were groundbreaking for men and women around talking about sex. And they also had excellent journalism and interesting interviews. Everybody knew that people bought it for the sexy pictures. But around that was a dialogue. Hugh Hefner and my father both ran magazines that worshiped the mystery and sexiness of women. And it’s easy in 2021 to look through a lens of political correctness and find those magazines wanting and out of step. But they weren’t out of step in their own time.

And Hustler was…

When Larry Flynt came around, he literally defiled that. And it was about defiling women. The more he could defile them, the better and the more he sold copies. His audience was interested in women being crammed into a pit of degradation. I know we’re not supposed to talk ill of the dead. Believe me, I’m holding back based on that. My opinion of him was that he was a bad publisher, and his product was revolting.

Today, what journalism products do you admire?

That’s the New York Times, the Atlantic, Washington Post, and BBC, and The Wall Street Journal is very good. There’s an awful lot of excellence out there. But it’s only really 1 percent of the volume. And I want Spin to be in that 1 percent. And I consider Rolling Stone and Pitchfork in the 99 percent of mediocrity, they’re just churning out the same old crap every day. And I said to the Spin guys, I said, let’s be aware of the reader, the visitor, the viewer is listening, and listening personally.

Looking back, what was your favorite Spin print cover?

The Search for the Soul of Rock ‘N’ Roll [from August, 1991] is probably my favorite cover because the issue as a whole was the most imaginative one we ever did. I told all of my editors and main writers to meet me at the airport at a certain day and time. And I said to them, “Pack for cold weather and hot weather.” They said, “Where are we going?” I said, “You won’t know until 10 that morning.” It was then that I handed them plane tickets and cash for expenses. And I said, “You’re going to Alaska. You’re going to New Orleans. You’re going here, and you’re going there.” We sent them out all over to go find the soul of rock and roll. And I said to each of them, as I gave them their [plane] ticket money: “I didn’t want you to have any time to think about it because then you’ll go with preconceived notions. Just go find the soul of rock and rock. You’ll know when you see it.” And it was the most spellbinding issue.

In the last two months, your team has published a couple of particularly intriguing pieces: one about the birthplace of jazz, New Orleans, enduring the pandemic, and another examining how three women are revolutionizing trap music with gore and fetishism in Romania’s hardcore scene. Is getting Spin back to that “In Search for the Soul of Rock ‘n’ Roll” level of journalism a goal?

Absolutely, and we’ll get there. Considering how long previous owners left Spin out in the rain, we’ve already come a long way towards making it a vibrant, smart hub for music and cultural reporting again. The other part of the answer is that, in a way, that kind of journalistic magic can never be struck again, in the same way people will never chiefly communicate by mailing each other letters again—because the physical method of producing and delivering such a package has irrevocably changed. We can come very close to that kind of creative ambition, but so much of the joy of it was its linear form, and the mystique of surprise and discovery. That was like reading by candlelight versus reading under Klieg lights, which is what media is today.

You might also like