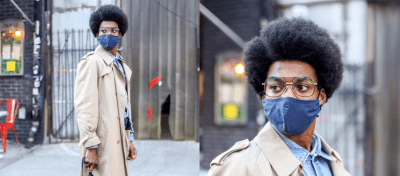

Photo by JD X on Unsplash

In praise of reality TV as ‘postmodern art par excellence’

This Brooklyn writer says don't feel guilty about loving reality TV (even though it may give us our first 'Real Housewife' president)

We caught up with Syverson to discuss being an unabashed Bravo network fan, the pitfalls of moralizing entertainment, the real White House potential for our first “Real Housewives” president and more.

Your book comes out just as many of us have been hoovering up reality TV during the pandemic. How long have you been a reality TV fan?

It was part of the culture in high school in the early to mid 2000s, but I was never hugely into it. My first real reality TV addiction was during college when “Rock of Love” was on VH1 and then “Jersey Shore” was a really big turning point, in terms of the quality I could expect. For a few years I remained interested, but I was not yet the huge superfan I eventually became.

Then I started watching “Vanderpump Rules.” I got really, really into it, which led me to “Real Housewives” and the broader Bravo network. It’s like falling off a cliff: there’s so much of it and it’s so deep and fascinating. I was interested in what was so special about reality TV that makes it so immediately compelling, as well as how it relates to identification, psychoanalysis and how we form ourselves.

You never seem to judge watching reality TV as either bad shameful. People might assume it’s addictive because it appeals to the lowest common denominator. But you’re saying it can actually be a valuable form of entertainment.

At least as valuable as other forms of popular entertainment, like comic books or superhero movies! Even cable news is such a big, supposedly enlightened part of how people entertain themselves, but really it’s just as trashy as anything else.

I wanted to write something that took the genre seriously and engaged with a leftist perspective but is also fundamentally from the perspective of a fan. I want to advance my and other people’s enjoyment of the genre, rather than tear it down.

Can you give us a teaser of the connection between reality TV and left politics?

We are in this very unique moment where we literally had a reality TV star serving as President of the United States: It was important for me to address that fundamental crossover in the book. Cable news, Twitter and podcasts also skirt the edge between entertainment and journalism in a way that dominates our whole culture.

During the Trump years, there was a real shakeup in social reality and what was considered true. “Post-truth politics,” “fake news” and “alternative facts” were the buzzwords of the era. While reality is often assumed to be scientific or objective, truth is formed socially through many things that are not real in a tangible sense. It’s very naive to think that there’s some kind of objective reality that we’re all living in. Reality television and the questions it raises about authenticity, behavior and social practices are very relevant to the question of what is real and how that relates to politics.

A recurring theme in ‘Reality Squared’ is how reality television is filling voids of romance, intimacy and meaning in contemporary life. Explain that.

The clearest example of that is in the chapter “Having it Both Ways on ‘The Bachelor’.” The basic contradiction of the show is that it’s the most conservative, heteronormative romance show on television, yet it’s extremely popular with professional managerial feminist women. I don’t consider myself a particularly conservative person, or even terribly romantic, but I love “The Bachelor.”

During times of political activation and change related to sex and gender, such as the #metoo movement, there is a disruption to our concept of romance. We want what was good about tradition but we don’t want to go back to all the bad and oppressive parts. “The Bachelor” creates this strange, hyperreal space where we can explore these contradictions. Something like chivalry can almost only exist in this bizarre fantasy space that reality TV creates. I wanted to explore what makes a show like “The Bachelor” so compelling in spite of what we tell ourselves about our values.

You suggest that part of what’s so refreshing about reality TV is that unlike most other contemporary entertainment, it’s not pushing a moral takeaway or political imperative on its audience. Why do you think that’s so necessary?

[Pushing a moral] often results in entertainment that feels condescending. The message is prepackaged and preapproved: you’re allowed to enjoy this movie because it’s feminist or diverse. That robs the audience of any challenging engagement with the work and doesn’t create a satisfying experience.

Reality television is totally different. I wrote about “Vanderpump Rules” for the chapter on ethics, because it’s the show with the most immoral, duplicitous behavior. What’s so fantastic is that those human behaviors are presented quite neutrally, and because they’re real people it’s hard to get to the bottom of who is the good or bad guy. In shows like Breaking Bad or The Sopranos where you have this anti-hero thing going on, there’s still a deliberateness to that moral ambiguity. In contrast, the social mess of “Vanderpump” Rules is much more interesting to judge from a moral perspective, with questions of redemption and forgiveness. Fictional characters invite a final, moral judgement in a way that real people don’t.

Over the last year especially, there’s been a politicization of reality TV. A number of cast members were fired from “Vanderpump Rules” for racist behavior. Even the “Real Housewives,” as divorced from the political “realities” of day-to-day life as they are, must weigh in on last summer’s uprising. What are your thoughts on that?

I think it’s a mixed bag. When you can see how obvious and pandering those decisions are, that’s bad reality TV. But, it’s inescapable, because it is reality TV. You couldn’t make a show about people’s lives in the summer of 2020 without making reference to everything that happened.

There were some very necessary storylines that I found interesting and chaotic. On “Southern Charm,” we saw Kathryn Dennis’ understanding of this political moment, her family history and controversies in Charleston about things like confederate statues play out. I think Kathryn was being herself and she was absolutely vilified and torn to shreds for it. I want to see these intense political issues on these shows when they’re organically part of people’s lives.

I noticed you tweeted that Bethenny Frankel from ‘Real Housewives of New York’ is going to run for president. Any other predictions about the future of reality TV?

I’ve long suspected that at some point Bethenny Frankel would have political ambitions. She’s such a driven and ambitious person, which I say neutrally. She did a lot of Puerto Rico relief work and it seemed like she was doing better than various governments. Then I saw that she has a show that sounds just like “The Apprentice” and I thought, “She’s headed right for the White House!”

Right now, Caitlyn Jenner is running for Governor of California. I wouldn’t be surprised if we saw more of reality television as a springboard for political office. A lot of people would think of that as a horrible disaster for our political system. I’m going to stay agnostic. I don’t know how good of a president Bethenny would be, but she can’t be any worse than the existing players!

Ha! Bad behavior is rewarded on reality TV, in that the most diabolical characters can be the most entertaining. Some people would be alarmed by those behaviors being rewarded in politics, but they already are.

That’s the thing. There are perverse incentives in the pharmaceutical and finance industries and those people make it into politics. They’ve done a lot worse than thrown wine in someone’s face!

Any favorite Brooklyn reality TV moments?

There’s one moment that comes to mind from early in “Real Housewives of New York.” Alex McCord and her very strange husband lived in Brooklyn and she always felt so alienated because no one respected it. She was yelling at someone and was like, “You are a mean girl and you are in high school. While you are in high school, I am in Brooklyn, trying to survive in this economy!” It was an absurd moment.

You might also like