Photo courtesy Bill Frisell

Gentle guitar giant: Bill Frisell is still learning

The beloved jazz guitarist discusses emerging from lockdown, his surprise pop-up shows in Brooklyn, collaborating with Elvis Costello and more

Bill Frisell likes to keep busy. Not only did the beloved jazz guitarist put out his latest album, “Valentine,” in the middle of a pandemic, he was even able to play some live shows. Sort of. Along with a few fellow musician friends, Frisell performed a few pop-up shows on scattered Brooklyn stoops to the delight of stir-crazy neighbors.

To be there was a balm. Frisell, whose career spans four decades, is an understated bandleader who blends folk, rock and country into his spare and often haunting performances.

Now, after many months of waiting, Frisell is back on the road. Again, sort of. He recently caught a flight to Washington state to visit his daughter. “I was always complaining about having to get on planes all the time,” he tells Brooklyn Magazine. “This was the first plane trip since [the pandemic] started.”

From a quiet corner of Washington woods, Frisell gave us a call to talk about his impromptu pop-up performances, his approach to making music, his love of Bob Dylan, still learning how to play guitar and the gradual return to live shows in 2021.

This interview had been condensed for clarity and length.

What has your overall mental state been like through this pandemic?

Oh, man. I’ve just been wondering myself. I guess it’s gone through so many different stages. Like right now, there’s just a sort of exhaustion from the whole thing. I mean, I’m feeling more hopeful now that we’re coming out of it, but it’s sort of also hitting me how devastating it’s been. I feel like I’m just depleted.

For a lot of us, these months have been about finding those small moments of joy where you can kind of feel like everything’s okay. And your pop-up shows in Brooklyn were one of those moments for a lot of people in the community. Were those performances as much of a comfort to you as they were for us?

Incredible. It was such a relief. I remember the first one: Just to play was like, wow, because that’s been my whole life. The first moment I got a guitar, whenever I’ve ever touched a guitar, when I was a kid, it was always about being with other people. Music, for me, it’s about being with people.

So your idea was basically: Okay, let’s go out on the porch and play a little and we’re just gonna see what happens. No real plan, but just doing it.

Yeah. The thing that started happening, my friend Tony Scherr lives sort of between Carroll Gardens and Red Hook, that’s where I did it. We’ve done that a number of times. It’s so awesome because he’s lived in that neighborhood for maybe 30 years, he’s been in the same place. So he knows everybody on the block. But it’s super spur of the moment, like we’ll just say, ‘Oh, do you want to play?’ and I’ll just go over. And we don’t really tell anybody. Those were super not publicized at all or anything. The neighbors are so cool that they would block off a couple parking spaces in front of this place and then put some chairs out there. Those really saved me.

Your friend, the producer Hal Willner, passed quite early in the pandemic. That was in April. How did that loss impact you early on?

I think about it every day. It also made it [the pandemic] like, wow, this is real, this is not a joke. I still can’t hardly believe that he’s not here. Soon after I moved to New York, it was 1979 when I came and just about a year later was when I met him. So 40 years I did stuff with him and he’s just such a big part of what my music is. One friend of mine, Marc Ribot, who was friends with him too, he said “it’s like you wake up and the Empire State building isn’t there anymore.”

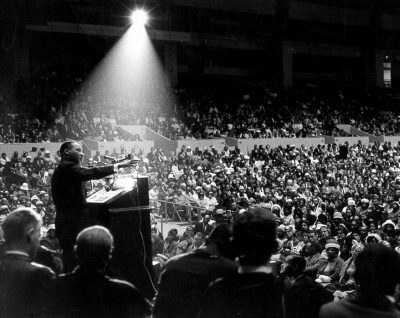

Your most recent album, “Valentine,” came out last summer and I couldn’t help but notice that the song choices on it seem very of the moment—”What the World Needs Now Is Love,” “We Shall Overcome”—but you must have chosen those tracks before the summer of protest.

All those songs, there’s always some reason. When we made the album, we didn’t know that George Floyd was going to be killed. But all those things were happening, other versions of all these same things. They’re always happening. Some people thought I even did it because of what was going on, but it’s always gone on. As long as I can remember, there’s a reason for those songs.

That was your second album on Blue Note. How do you like the label so far?

It’s amazing. I’ve gone through a few different labels and I just feel so lucky. You know, there’s pluses and minuses. But they’ve been super supportive. you know? The first album on their label, “Harmony,” we had finished the album, the album was done and there was no label for it. And [Blue Note Records President Don Was] just said, “Man, yeah, that’s terrific.” And then the newest one, he really came to bat for us there too. He’s been great. He’s the head of a company, but he’s a playing musician and he understands timing. The music is always moving and evolving.

You mentioned the “Harmony” record, that was also a really lovely album. Do you have plans to maybe record with those guys again? That quartet?

Well, I hope so. Yeah. Like I said that music is always moving. It’s like a photograph, you capture what was happening at that moment, and then you just keep moving on ahead. So we played a lot since that album came out and we’ve got tons more songs that we do, and the music has changed a lot.

You make it sound very easy. But I think that’s one of the things that’s most impressive to a lot of people about your body of work in particular, is that you put out new music and new albums so regularly and so consistently. And that’s not always a very easy thing to do.

Well, I don’t know if it’s easy, but I’m trying my best all the time. [Laughs.] Every bit of music is like a question. It’s like if you play one note, it’s like asking me, “Okay, what’s the next note?” It fires up your imagination. And then you play a chord and it makes you think of a melody that fits with the chord or something. You play a song and then you go, “wow, where did this song come from?” It’s like this annulus, it keeps pulling you all the time. It’s the most amazing thing. No matter how many times I play the same song, there’s always something in it that I didn’t realize was there.

I’m quite curious about your writing process. Is that how you usually go about it? You start with a seed of something and then go from there?

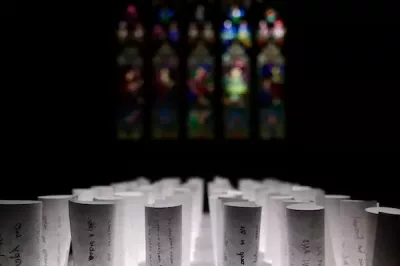

Yeah. During this time, it was like, thank goodness I got my guitar. Suddenly, I had all this time to practice and writing and stuff. And now I’ve got these piles of notebooks that are just filled with stuff that I’ve written during the year, it’s really insane. But yeah, I compare it to drawing or doodling almost, I still use paper and pencil, I’m not comfortable with the computer at all. But just kind of following my imagination. It can start with just hardly anything, just a couple notes. And then it just starts generating. I try to not block it, that’s been a long process of learning not to edit myself when it’s happening. Whatever comes out, let it come out. And then I can go back later and decide whether I like it or not. I don’t know if you do that with words.

What about writing or working in the studio versus playing live? How do you compare the two?

They feed each other. I love both of them. I guess if I had to choose, it would be just playing live. You know, that’s the real thing, in a way. I love being in the studio too, it feels so different. The audience always has something to do with how the feel works.

It’s funny you should say that because I was thinking about that a couple of weeks ago. I watched your live stream show from the Village Vanguard. And it was really nice to see a group of musicians up on that stage playing a show, but it was also so bizarre to not see anybody in the seats or hear any sort of interaction between the songs. Is that as weird onstage as it is to watch?

Pretty weird, yeah. I’m lucky to get to do that. Just to get to go into the club was like, wow. I remember just walking down the stairs. Since the pandemic, I’ve done it three times or something at the Vanguard. I guess it was August the first time we did it, and I remember just the feeling of going into the club … I felt like this weight lifted off. But yeah, then you’re playing and it’s just complete silence.

Playing live gives everything a much more genuine feel. But mistakes happen. What’s your approach to making mistakes?

Well, mistakes are amazing actually. You learn some of the best stuff. You could even say that there aren’t any. Something happens and then it’s what you decide to do next is what can make it a mistake. Or maybe you could turn it into something that’s not a mistake. I was reading something — Herbie Hancock, who was playing with Miles Davis, talking about some time early on when he was playing with Miles. And he played a chord that was wrong, and then Miles immediately played a note that made the chord sound right. It’s not like a contest of who’s right or wrong. It’s like if everybody’s trying to rescue each other, watch out for each other and the idea is to try to make something cool out of whatever is happening in the moment.

Something that I really like about your style of playing is that it’s very simple, but not in the dull or plain sense, but in a way that just really seems to allow whatever song you’re playing to kind of breathe and open up. And I think you’ve said before that simple playing like that can be and is just as good as complex playing. Is that a style that you’ve really consciously tried to develop? Or has that just kind of come naturally?

Well, no, it’s conscious. Part of it is just trying to be as clear as I can be, like trying to get to the essence of what it is I’m playing. I try not to just play a bunch of stuff just for the sake of playing it, but try to make every note really count. But also, we all have limitations, there’s so much that I can’t do that I wish I could do on the instrument. You take what you’ve got. You know, I can’t play super fast or I can’t do this or that, but despite that, I’m going to just try to play something that means something.

People might assume that because you are such a well established and well respected musician that you’ve got it all figured out.

No way is it figured out. [Laughs.] I’m serious when I say that I feel like I’m just at the very beginning. That’s what took me a long time to come to terms with. The first time I picked up a guitar, there was this infinite thing in front of me. So you pick it up, and you try to play something and you move ahead a little bit. And it feels exactly the same now. Today I pick it up and there’s this infinite thing out in front of me that I haven’t gotten to yet. And I’ll never get to all of it.

The musicians that you worked with on, for example, Valentine—bassist Thomas Morgan and drummer Rudy Royston—they’re younger than you are. And I would imagine that there’s certainly lots and lots of younger musicians today who see you as a trailblazer in jazz music. Do you see yourself that way?

[Laughs.] I’m just trying to keep learning. The people that I play with, I know they’re younger than me, but they’re like my teachers, you know? I choose them because I want to learn from them.

You played on and you also have two co-writing credits on Elvis Costello’s last album, “Hey Clockface.” You’ve worked with him a couple of different times. Can you tell me a little bit about what it’s been like to work with him?

That was another pandemic thing. [Trumpeter] Michael Leonhart worked on that album with Elvis. At the very beginning of this lockdown thing, he contacted me and said, “I’m working on this album. Could you maybe play on a couple things?” And then, we all had all this time. And I said, “Well, yeah, I could do it.” And I did a couple of these things for him and I didn’t even know what they were. I just played some long thing, and then some time later he said “Oh, I gave this to Elvis and he wrote some words.” It just happened.

I noticed that you’re playing a virtual tribute show for Bob Dylan’s birthday later this month. I’ve heard you play some of his songs over the years, and I’m wondering what is it about Dylan, both as a songwriter and as a person too, that draws you to him?

That’s huge. He’s this gigantic presence just in the way we think. It goes back to either seventh or eighth grade. I’m, like,13 years old or something like that, and his very first albums had started to come out. And my English teacher was so cool, he would play us Bob Dylan records in our English class. Then it just started exploding. It was just a gigantic impact, how that music hit me—the words, it was like he was talking to me. He’s somebody that has always stayed with me.

He’s always reinventing how he’s doing things and exploring new avenues and heading in directions that you might not expect. What did you think of his last record? “Rough and Rowdy Ways?”

I loved it. Yeah, that thing about just not settling into what’s safe. I went to see him—wow that’s weird, that was the last time I saw Hal [Willner]—but I went to see him at the Beacon Theater in the fall before…

I think we were at the same show, then.

He could do songs that he wrote 50 years before, but it’s like, totally transformed into a whole nother thing. It’s not fixed, you know, in a certain way of doing it. It’s totally alive still.

If you could play with anyone today, living or dead, who would it be?

Oh man, it’s just so many. I’ve already gotten to play with more than I could ever dream of. But I never got the play with Miles Davis, or I never got to play with Sonny Rollins.

Well, I’m gonna bring it back to the present. I know you’re playing two sold out dates Industry City [May 22 and 23] later this month, live, in-person. That’s wonderful. Do you have any big plans or surprises for that show? Or are you just looking forward to being out there?

Oh, just to play. And it’s two days, which is awesome.

Even better, yeah. And then moving forward through the summer, what are your plans? What are you looking forward to?

Well, when I look at my calendar from this whole year, it’s like just all this stuff that was crossed off. But we’re supposed to go to Europe in July. We’re all vaccinated now. Even just a couple weeks ago, I was thinking, you know, this is never going to happen. But now maybe it will.

You might also like