Courtesy the Cyclones

A king without a court

When the Brooklyn Cyclones kick off their new season, longtime mascot-emcee King Henry won't be there for the first time in a decade

Guy Zoda, better known as King Henry, closes his eyes at home in Staten Island, and, even though it’s early spring, the synapses going off might as well be July fireflies. His mind is back at Coney Island’s MCU Ballpark, where he’s standing behind second base with kids and parents circling the bases in front of him after a Brooklyn Cyclones game. He can hear their jolly noises mix with Semisonic’s “Closing Time,” and the hair on his arm stands up.

“I would watch them run around, and I would get goose pimples,” Zoda says. “It was true joy—the love that you see.”

Zoda has been the Cyclones’ master of ceremonies in the guise of King Henry for the past decade, during which time he’s been a fixture at the ballclub, known for his signature red polyester vest, pants and crown combination and his court-jester antics between innings. But he will not be at the Cyclones’ home opener tonight because—for this reason over all others—he’s no longer an employee of the ballclub.

For diehard fans it might sound like a shame. But the King abides. Zoda is as yin-yang as a 53-year-old white dude on Staten Island can be. And his situation has to do with finding a balance between ego on one side and peace of mind on the other.

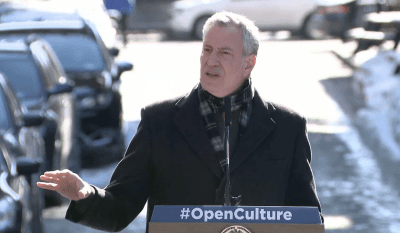

Zoda in character (courtesy the Cyclones)

That’s showbiz

“I went years and years of going, and going, and going, and going,” says Zoda. “I didn’t know I was a workaholic.”

When Covid shut the world down, and everyone took a long look into their mirror, Zoda wanted better and feared backsliding into worse. He once weighed three bills, after all.

The main reason King Henry won’t be on the field tonight stems from a business decision in January 2020, when Zoda re-negotiated his deal with the Mets’ High A affiliate and became an independent contractor instead of a full-time employee, which he had been since 2011. As any seasoned freelance worker—writer, graphic designer, dogsitter, etc.—knows, when the economy tanks, the 1099 folks are the first to get cut. Contract entertainment talent at minor league ballparks is no different, especially when capacity is limited to 1,300 like it will be at MCU until at least July.

So, as baseball returns to the borough for the first time since ‘19, Zoda won’t be on hand to do his King Henry thing. The Cyclones tried to work out a deal where he’d perform every so often, but the two sides couldn’t find enough common ground.

“I don’t take it personal,” Zoda says, “because, listen, I know showbiz.”

Pre-pandemic, he had his reasons for wanting to slow down, do less with the Cyclones, do more with King Henry for other organizations and enjoy time with his family. Zoda and his wife, Xiling Zoda, have a daughter at St. John’s Law School and a son in high school who is a jiu-jitsu competitor and on the wrestling and fencing teams. After all, for Zoda, his boardwalk ballpark ascent started with mustardy kismet.

‘Spitting distance from the circus’

Zoda began his affiliation with the team in 2003 as a face-painting vendor. He was, impromptu, asked one night to sing “Happy Birthday” to a youngster in the stadium because the emcee at the time was unavailable, and it went well enough they started having him lead “Happy Birthday” singalongs for others. Then, when he was caught on the stadium scoreboard video screen eating a hot dog one night, wiener sales skyrocketed. King Henry has been a Cyclones’ mainstay since.

“Minor league baseball’s just spitting distance from the circus,” Zoda says.

To hear him tell it, Zoda’s life turned into a high-wire act of worry. Zoda, a Benshonhurst native, is old enough to remember Saturday Night Fever-era southwest Brooklyn and knows how to do the hustle. So, he pounced on the Cyclones opportunity and over time expanded his role with the team, becoming the brand’s liaison with dozens of elementary schools and, ultimately, creating a human face for the team’s marketing.

The human-face aspect of King Henry has set Cyclones marketing apart from most minor league ball clubs, which typically pay someone a part-time wage to put on a furry costume and roam the stadium as a character that could be played by, well, anyone. The Cyclones have Sandy the Seagull and Pewee, for instance. Across the minors, “ballpark characters” like King Henry are rare breeds, says Benjamin Hill, MiLB.com reporter and the publication’s resident expert on the subject. The St. Paul Saints have Sister Roz, the Reading Fightin’ Phils have The Crazy Hot Dog Vendor, and the Tri-City Dust Devils have Erik the Peanut Guy.

And then there’s King Henry.

“These sort of characters make up a big part of the gameday experience for the teams who employ them,” says Hill, who was surprised to learn that the Cyclones and King Henry were going their separate ways. “End of an era.”

A spokesperson for the Cyclones says the team is open to bringing back King Henry at a later date, but both sides seem noncommittal.

Whistling once again

Zoda invited all of his former girlfriends to his nuptials with Xiling; in other words, he says, he doesn’t do messy break-ups. “I don’t have a bad word to say about the Cyclones,” he says.

King Henry, a character Zoda developed close to 20 years ago, also had regular appearances at Victoria Gardens and Wollman Rink in Central Park, but they were also cut under Covid. So, he had little to do besides collect unemployment and focus on self-improvement. For years, he had the build of a donut maker, akin to a Jackie Gleason or a Ned Beatty. In 2019, he began going to the gym and losing weight. After the pandemic started, he admits he was tempted to quit on his progress. But instead, he continued working out at home every day, walked with weights in his backyard, practiced jiu-jitsu with his son and honed his skills as a “quarantine chef.”

Since Cyclones fans last saw him, Zoda—who describes himself on LinkedIn as a “magician/clown/sandwich lover”—dropped 80 pounds, and now weighs 240. What he lost around the waist was replaced by a new heft of self-awareness.

“I didn’t realize how burnt-out I was until I got my psyche back—until I got balance,” he says. “I have had a tattoo of a yin-yang on the center of my chest from when I was in my 20s. So I was always very centered, always the guy who was like, ‘Hey, there’s other ways to think about things.’ But when you’re going seven days a week and you have the pressure of the world, sometimes you don’t stop to smell the roses anymore.”

Xiling, standing nearby, looks up. “You started whistling again,” she says.

Zoda was recently back in Coney Island shooting a scene as a clown for an indie movie being made by a friend on a Saturday. “I had about a dozen people come up to me and say, “I will see you at the Cyclones,’” Zoda says. “I’m, like, ‘No, I’m not going back.’”

That weekend, Zoda announced his decision to move on via Facebook, triggering nearly 400 comments of support.

“I got to watch my own funeral,” he says.

How many kings can say that?

You might also like