Photos Courtesy of MATTE Editions and Gitterman Gallery, New York

A photo collection that captures New York at the very dawn of AIDS

In 'FEVER,' Allen Frame's candid 1981 photos capture a time of hope and innocence—and they are all the more tragic for it

In a new book of color photographs, all shot in 1981, Allen Frame revisits a time that gave rise to an aesthetic that was distinctly New York. A circle of friends, many—though not all—gay men, made art at a specific moment in city’s history, though perhaps not what you’d expect.

“FEVER,” Frame’s personal documentary of that time, captures young people living their lives before any of them had ever heard the word AIDS—before any of them were aware of the deepening tragedy that would claim the lives of many of the young artists pictured in this book.

What’s so striking about the photographs is “the irony of that year,” says Frame, “the mood and palette of the pictures versus the impending pandemic.”

Something very important has been lost in the passing decades that makes the 1980s worth revisiting again. It was the last decade that believed in the future. Looking back, 40 years later, the pictures are a deconstruction of that time. Perhaps the title of the book could have been “The Way We Were.” Each photograph is personal, political and poetic.

1981 was a pivotal year: New York City subway fares went from 60 cents to 75 cents; Keith Haring had his first solo exhibition; IBM unveiled its first personal computer, forever changing access to technology, and The New York Times wrote: “Rare Cancer Seen in 41 Homosexuals,” a headline that forever changed a community.

Darrel Ellis, himself a prolific artist, who would die of AIDS in 1992 (Courtesy of MATTE Editions and Gitterman Gallery, New York.)

Being a fixture of the rapidly changing New York art world of the 1970s, Frame was introduced to artists and photographers such as Peter Hujar, Darrel Ellis, Frank Moore, Kenny Scharf, and had already known others such as Nan Goldin and David Armstrong from his college days. These were the artists whose visual language was considered groundbreaking in New York City’s East Village—the epicenter of contemporary art. This was art that embodied the spirit of the time, drawn from ideas and experiences of the life that was swirling around them. This was a visual language that Frame had already begun to embrace.

Painter Kenny Scharf and underground performer Patti Astor (Courtesy of MATTE Editions and Gitterman Gallery, New York.)

The photographs in “FEVER” are taken in the style of family snapshots, using only available light to give the pictures a warm and sympathetic appearance. In only one does he use a flash. All are in color.

The use of color film in 1981 was still relatively rare. Not only was it more expensive than black and white, but art critics did not take it seriously. It was considered tacky and cheap, the stuff of cigarette ads and family albums. Plus, it was not user-friendly. When Kodachrome (the first successful color material used for both movies and still photography) was first introduced, it was so complicated that even Ansel Adams, a darkroom wizard, had to rely on labs to develop it.

The first watershed moment for color photography took place just five years prior to the photographs in Frame’s book. In 1976 the Museum of Modern Art launched a legendary exhibition, “Color Photographs by William Eggleston,” the museum’s first-ever show of photographs in color. The exhibition was accompanied by the museum’s first publication on color photography, a posh 112-page hard-cover book with 48 color plates. This was very unusual for the first solo exhibition by an artist few people had ever heard of.

It was also the most hated show of the year. Shot in the Mississippi Delta, where Eggleston lived, the pictures were of “nothings and nobodies:” a child’s tricycle, a dinner table set for a meal, and so forth. “Perfectly banal, perfectly boring,” one critic wrote, “a mess,” wrote another.

Reflecting on an Eggleston photograph, Ansel Adams quipped: “If you can’t make it good, make it red.” Robert Frank chimed in with “black and white are the colors of photography,” and Walker Evans once wrote, “Color photography is vulgar.” These photographers all had had major success working in black and white, so why would they support the use of color?

But a younger generation was about to.

Even though the Eggleston show was trashed by just about everyone, it marked an important shift. Color photography was about to be absorbed into mainstream art.

By the time of the MOMA exhibition, Frame was aware of the elder photographer as both had been born and raised in Mississippi. In 1974, after graduating from college in Boston, Frame returned to his hometown and was introduced to Eggleston. He, too, found Eggleston’s photographs banal. Frame’s approach to photography was more psychological, and certainly more personal than tricycles.

Frame initially studied photography while attending Harvard University, first under Henry Horenstein in a community center in Cambridge, and later under Bob Hower at Imageworks, also in Cambridge. But his biggest influence was to come from movies. “I had been a film buff since childhood and in Cambridge I saw a lot of repertory cinema,” he says.

Frame was especially drawn to the films of Antonioni, Fellini and Visconti, directors who had developed a more subjective, stylized, approach to filmmaking. They would become a huge influence on his artistic sensibility: “I acknowledge, for instance, that abstracted psychological narrative of Antonioni, his framing, his tenuous connection to plot, as an important influence on my own photography.” Objects, articles and architecture are a signature of Antonioni movies, films that nail the zeitgeist of the moment, in this case, the sixties. In an interview from 1969 Antonioni said: “until the film is edited, I have no idea myself what it will be about. Perhaps it will only be a mood, or a statement about a style of life. Perhaps it has no plot at all.” And that is, perhaps, a good way to describe the photographs in “FEVER.”

As Frame explains, “My technique is kind of like that of a street photographer using a 35mm camera shot with very fast reflexes, even when the scenes look slow and still. I am using foreground and background spaces split by walls or figures.”

The photographs in “FEVER” could be defined as genre, or, documentary photography. Frame has captured friends in real-life situations, whether in their apartments, on the beach, or on the gritty streets of New York. They are all candid, not posed, but carefully framed to appear as though caught on the wing. Each is imbued with psychological intimacy and abstraction.

One photograph that particularly jumps out is of a young man and woman in an apartment, a duality of light and shadow. They are split, rather, separated, by a partial wall. He is in the bathroom, bathed in soft, red light. There is natural light from an open window behind her, yet her body is in shadows, almost silhouetted. He is topless. She is fully clothed. Her right hand dangles a cigarette. There is a bed behind her. Are they lovers? Just friends? Frame puts space around his figures, and places them in different planes, “emphasizing the sense that they are in different psychological states of mind.”

Richard Elovich and Annie Ratti (Courtesy of MATTE Editions and Gitterman Gallery, New York.)

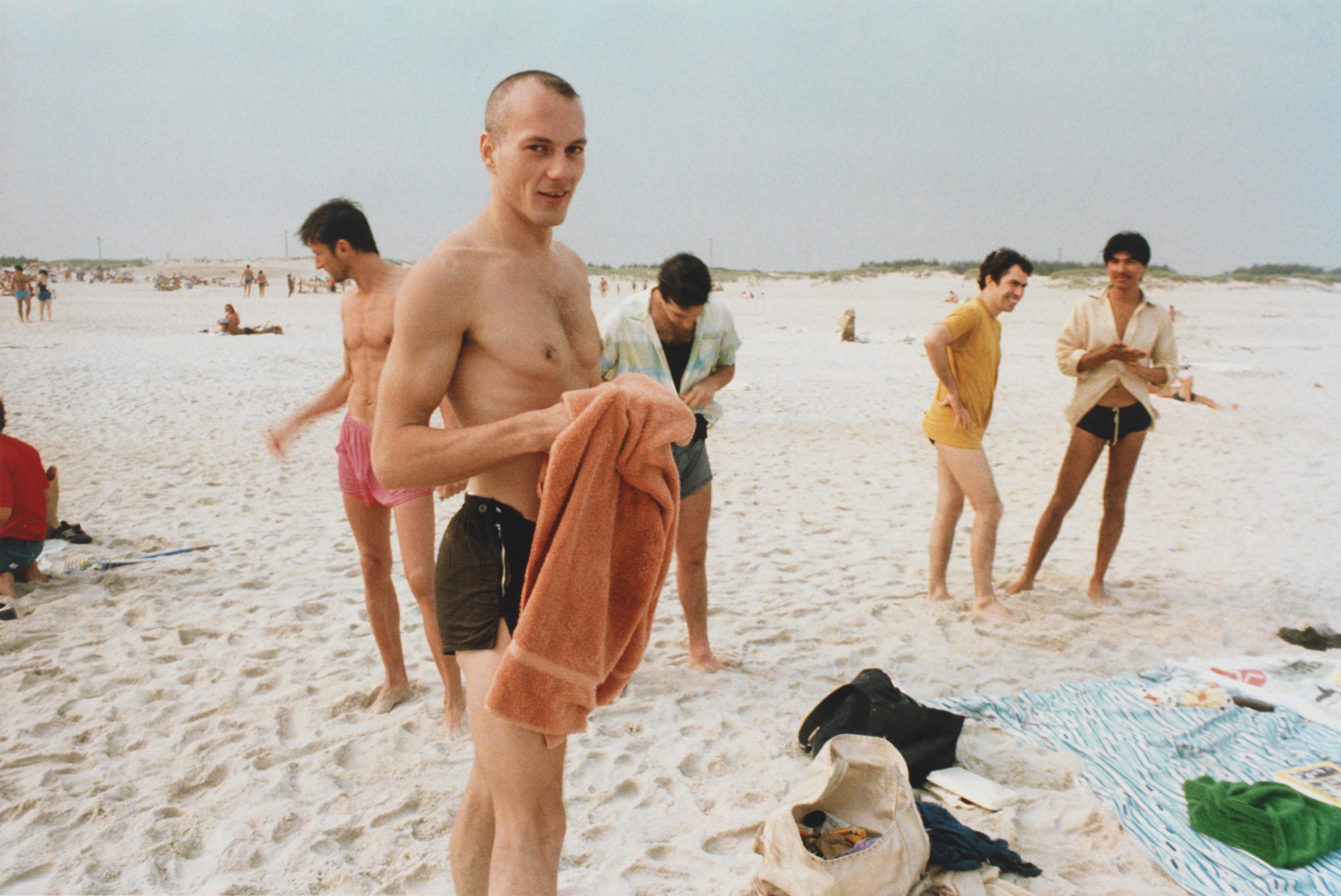

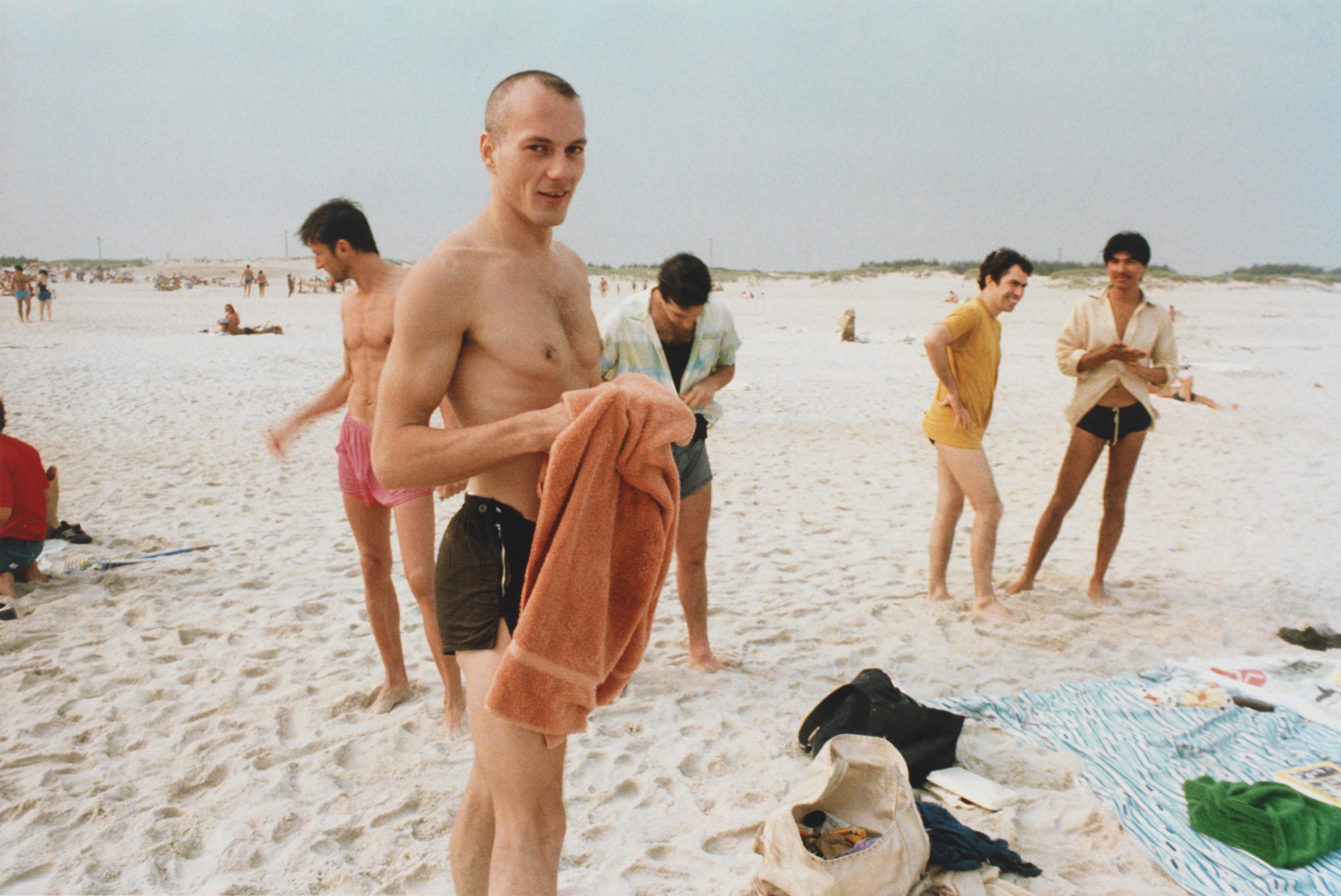

In another photograph, a group of young gay men are casually socializing on Jones Beach in the summer of 1981. The camera is an objective observer. One of them faces the camera while the others are in the background. They are not flirting. They are not touching. They are simply living their lives. While the photograph exudes happiness and innocence, when reflecting on it 40 years later there is a ghostly pathos too. This is a portrait of lives that would soon be eclipsed by AIDS.

(Courtesy of MATTE Editions and Gitterman Gallery, New York.)

Frame’s friend, photographer Nan Goldin, once said that she used to think she couldn’t lose anyone if she photographed them enough. Frame’s work shares Goldin’s empathy, but he sees his projects more as an unfolding of a point of view than an attempt to hold on.

Nan Goldin on her 28th birthday (Courtesy of MATTE Editions and Gitterman Gallery, New York.)

“FEVER” is published in an edition of 500 copies of 152 pages with 50 color photographs and text. The introduction is by Drew Sawyer, Philipp Leonian and Edith Rosenbaum Leonian, Curator at the Brooklyn Museum.

You might also like