‘Isn’t that being free?’: Free jazz veteran Alan Braufman returns with a tighter sound

On 'Infinite Love Infinite Tears,' the alto saxophonist's songs have more structure — but no lack of exploration

What does the label “free jazz” really imply? Does it describe a song without structure? Or perhaps a song that eschews typical tonalities and ideas? Maybe it’s a term hastily applied by listeners when they don’t know how to accurately describe the music they’re hearing.

At 72 years old — he turns 73 next week — the veteran free jazz alto saxophonist, flutist and composer Alan Braufman still doesn’t have a solid answer.

“Free jazz is an interesting title for music because what does it really mean?” Braufman says. “Somebody will come up to me, at times, and say, ‘You’re not playing free jazz because some of the stuff you [play] has structure.’ I say, ‘Well, that’s what I wanted to do. Isn’t that being free?’”

The genre has been misunderstood since emerging in 1959 when saxophonist Ornette Coleman and his quintet played a two-week residency at Five Spot jazz club in the Bowery — which would later be nicknamed “The Battle of the Five Spot.” With his plastic saxophone in hand, Coleman played raucous, exploratory sets with a crew that shook the foundation of New York jazz to its core.

In 1960 Coleman released “Free Jazz: A Collective Improvisation,” giving a name to the genre he was pioneering. Contemporaries like Miles Davis and John Coltrane, among others, soon started embracing free jazz, inspiring future generations of musicians, like Braufman, to further push the boundaries of free jazz.

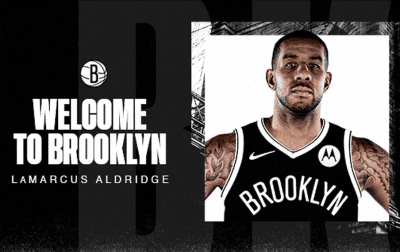

Braufman, an integral member of the 1970’s New York free jazz scene, is releasing his third album, “Infinite Love Infinite Tears” on May 17. In many ways, it is a thoroughly Brooklyn record.

Braufman (Photo by Gabriela Bhaskar)

‘This beautiful music in my head’

Braufman was born in Brooklyn and raised on Long Island before heading to the Berklee College of Music in Boston. He moved to Manhattan in 1973 and relocated to Salt Lake City in the ‘90s — he visits Brooklyn often. The album’s lead single shares a name with the borough, and the album itself was recorded at The Bunker Studio in Williamsburg. All the musicians who played on the album live in Brooklyn.

The idea for “Infinite Love Infinite Tears” came to Braufman during a walk through Bed-Stuy last June. He went to see some friends play at Sista’s Place and decided to walk back the Clinton Hill apartment of his nephew Nabil Ayers — son of the jazz-funk vibraphonist Roy Ayers and producer of the album. He knew he wanted to record a new album but says, “That evening made me solidify my concept.”

“I had this beautiful music in my head … that’s pretty much the way I write, just listening to what’s in my head,” Braufman says. “I think it inspired some nice melodies, walking on a nice summer night through Brooklyn after hearing [my friends] play. I thought of that tune and ended up calling it Brooklyn.”

Over the next six months, Bruafman continued listening to the melodies in his head, resulting in a collection of new songs, five of which joined “Brooklyn” on the album. He assembled a team of musicians to play them — Patricia Brennan on vibes, James Brandon Lewis on tenor saxophone, Chad Taylor on drums, Ken Filiano on bass and Michael Wimberly on percussion — and recorded the album in November.

Compared to his previous two albums, 1975’s “Valley of Search” and 2020’s “The Fire Still Burns,” this is arguably Braufman’s most accessible album. That’s not necessarily a bad thing. “The Fire Still Burns” already saw Braufman distancing himself from the unorthodox sounds of his debut effort.

On “Infinite Love Infinite Tears,” the septuagenarian presents a diverse collection of songs spanning various genres, proving that he’s still exploring new ideas only under more structured settings.

On the album opener “Chasing a Melody,” rollicking solos from the band are bookended by an up-tempo melody tinged with calypso and bebop swing. It’s reminiscent of Horace Silver and his contemporaries from the sixties and will immediately get your toes tapping.

The title track is a more melancholic, Miles Davis-era style modal jazz tune with a perhaps bit of Pharaoh Sanders-inspired spiritual airiness to it. “Brooklyn,” on the other hand, is a breezy Afro-Caribbean-style track that perfectly captures the energy of the borough — specifically Bed-Stuy — on a laid-back summer night.

“Liberation” brings the album to its climactic end by showcasing Braufman does best — getting lost in a free jam. Throughout nine frenetic minutes, blaring horns, cosmic vibes and pummeling drums run wild. It feels appropriately placed at the end of the album — sure, Braufman explored new themes on the album but he couldn’t let listeners forget that the album and his career are anchored in the liminal spaces of free jazz.

Ayers remembers when he was working with his uncle to decide which tracks would make the final cut on the album, he pushed to include “Liberation.” Braufman agreed.

“He was like, ‘”Liberation” needs to be on the record, because it’s the only free song, and we have to have some of that,’” Ayers recalls.

Braufman acknowledges that on the album he distanced himself from traditional free jazz thematics. But he still feels he was free in his own way.

“To me, being free is just doing what you want,” Braufman says. “Which is exactly what I wanted to do.”

He also feels that, occasionally, musicians trying to make free jazz lose sense of the core identity of the genre. Sure, blowing your horn at full volume while your band freaks out can be cool. But are you actually free? Or are you restricting yourself to a preconceived notion of what “free” has to be, thus actually limiting yourself and the potential of your music?

“There’s so much in New York City right now in the free jazz movement, quite a bit of it is just improvisational, no composition whatsoever,” Braufman says. “I have a blast doing that, I love doing that, it’s fun. But if I’m putting my name on something I’m gonna plan it. If I were to do free jazz improvising all the time, as many do, I’d be denying myself one of the things I love about music, which is the writing.”

Another distinguishing difference between “Infinite Love Infinite Tears” and Braufman’s previous two albums is the absence of longtime collaborator and pianist Cooper-Moore. In his absence, Brennan’s vibraphone brings a sweet yet mellow quality to the album.

Whereas the vibraphone’s role in improvised music is traditionally linear, Brennan’s approach is unapologetically nonlinear. Instead of soloing like a saxophone or flute, she opted to approach her solos more like a piano or guitar, going so far as to use an electric setup including a whammy pedal with an octave setting to push the boundaries and range of the instrument. She credits Braufman for giving her and the other musicians “no limits” to their playing.

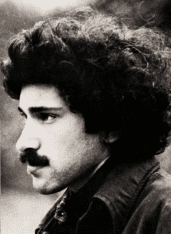

Braufman in 1974 (Photo by Bob Cummins)

“I felt extremely comfortable, I guess just the open invitation to just be free within that space was totally there,” Brennan says. “I think that’s the ultimate setup for best music making because there’s no limitations, even though you literally have some actual structural limitations on the page.”

As a kid, Brooklyn meant “very little” to Braufman. He preferred the “wasteland” of downtown — before Tribeca had its tony name — where he could hop to jams and see legends perform on a nightly basis. He worked as a sideman for improvisational titans like Carla Bley, Richard Landry and William Hooker, and played with the Psychedelic Furs. He moved to 501 Canal Street in 1973, which itself became a nexus of the 1970s loft scene.

These days, though, most of his friends and family live in Brooklyn and he finds himself going to more shows there than in Manhattan. He and his band will be playing “Infinite Love Infinite Tears” at National Sawdust in Williamsburg on June 7.

“Everyone’s in Brooklyn,” Braufman says with a laugh. “I might come in for two or three weeks and I don’t even make it into Manhattan.”

You might also like