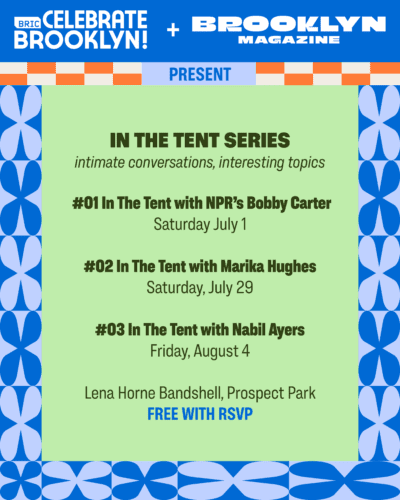

Muralist Katie Merz is making it up as she goes

A conversation with the artist at work in Industry City and on the eve of her new wallpaper collaboration

If you look closely at Katie “KT” Merz’s public art—an eye-catching mix of freehand shapes, words, splotches of color and patterns—you might notice people’s names, seemingly written at random. It turns out many of them, come from, she says, passersby who stop to speak to her while she works. On a 2018 mural Merz painted on the corner of Fenimore and Flatbush in Prospect Lefferts Gardens, for example, she included the names of dozens of people who had dropped by while she worked.

“I couldn’t believe how many people would come by and want to be part of it,” Merz tells Brooklyn Magazine (in person!), sitting with her supplies at an in-progress space at Industry City. “And they’d bring their friends by the next day and be like ‘that’s my name up there!’”

This quasi-collaborative style is helped by the fact that Merz—whose art can also be seen adorning both exterior and interior walls at places like the Brooklyn Bank, Dekalb Market and the Brooklyn Navy Yard, as well as in other cities like Austin, Texas, and Monterrey, Mexico—works without a set plan and entirely freehand. She’ll typically start out with a jotted down list of words, phrases or ideas she aims to include, and then works from left to right, with “no plan,” fitting in pieces “like a puzzle.” Merz views her particular style almost as linguistic—hieroglyphics of a sort—the result of her combined love of literature and imagery.

The Flatbush mural, courtesy of Merz

“I started breaking down language years ago,” she says. As a child, she read Lewis Caroll’s rebus writing, which used illustrated pictures and individual letters to depict certain words or phrases. “It made sense to me that you’d take a word and break it down into imagery … I just did it for fun. And then I did it outside once. I took a poem by [Rainer Maria] Rilke and I translated it into like, ‘this plus this equals this’ … And then I thought, ‘oh, this makes sense. This is great on a building.’ I did it on a barn and then that changed everything for me.”

Adding the bits that passersby offer, she says, creates not only a sense of participation, but also of ownership for local residents.

“It’s like I’m pulling in people to partake in it, so it’s mine and it’s theirs,” she explains. “That’s what I always say: ‘You’re helping me make this piece.’ So I don’t want to be that person that’s just plopping something up on a wall, I want to be part of the collaboration of the human beings that are here.”

Bringing upscale down to earth

Merz herself, who is 60, has been in Brooklyn all her life. She grew up in Willowtown, the lower portion of Brooklyn Heights close to the docks, where life, she says, was always buzzing.

“When I was a kid, you’d go outside and you’d enter into this whole hilarious non-stop theatre piece,” she said. “Everything was out on the street, you’d talk to everybody.”

That sense of constant social whirring was a large part of what she ultimately wanted to integrate into her artwork. At a certain point in her career, she realized she didn’t enjoy the seclusion of studio work and the more commodified aspects of the industry. The reality, unfortunately, is that art—or at least, “art” in the traditional sense of galleries and exhibitions—isn’t always accessible to everyone.

“That is so over for me,” she said. “It has everything to do with growing up here. Because the streets are everybody’s, it’s like what you make of it. And if you don’t have money, you’re really disqualified from partaking in that kind of thing.”

That doesn’t mean that Merz isn’t interested in expanding the horizons of her work. One of her current projects, a line of wallpaper that features her art as the primary design, launches today, a collaboration with A-Street prints. “It’s kind of a great transference,” she says—another way to bring art out of the upscale and into more inclusive settings.

The blue building in Bushwick, courtesy of Merz

Learning to let it rip

As a kid, Merz had watched her architect parents, Joseph and Mary Merz, also embody the idea of being connected with one’s own environment and giving back to those around you. (One of the Merz’s elaborate mid-century townhouses hit the market last year, a few months after Joseph Merz’s death in March 2020.)

“They were so involved in urban planning and having their house be not just built and lived in, we were a whole part of the block and the community,” she said. “I didn’t feel right about just being self-involved in my studio, like there was something wrong with that. It had to do with their constant consideration of community and the urban fabric. Like, you don’t just buy a house and live in it—you’re part of your neighborhood, and you’re part of your neighbors and you’re part of the whole larger fabric of New York.”

That fabric has changed and developed plenty over the last several decades, including a push for more public art. The pandemic especially, in her view, shifted the way many of us perceive outdoor spaces and what we do with them. Merz says she used to sentimentalize the old days of the city, but not so much anymore. “Now having lived long enough, I realized this thing is going to change forever,” she said. “In a way, I’m just like, ‘Let it rip.’ This thing is on its own course, and it’s beautiful.”

You might also like