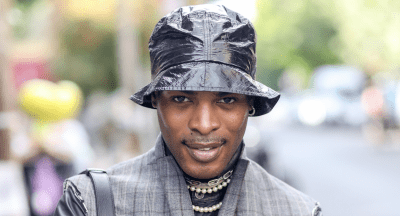

Hunt Slonem at 70: Bunnies (still) on the brain

The prolific painter is holed up in Brooklyn with his birds—and is enjoying, he says, 'a perfect moment in my life'

For more than five decades artist Hunt Slonem has been painting and reimagining his obsessions: butterflies, birds, bunnies, and portraits of Abraham Lincoln, whom he refers to as his Warhol Marilyn.

The Warhol reference is no fluke. Repetition plays a huge role in his work—and excess and extravagance define his life and art—both he and his brother Jeffrey were frequent habitués of Andy Warhol’s legendary Factory in the 1970s. But unlike Warhol, who famously declared his art to be a mass-produced commodity, Slonem does it all with his own two hands.

In addition to painting multiples of his signature motifs, he sculpts, makes prints, does watercolors, creates installations and collects antique furniture and historic homes—seven of them to be exact: four mansions and three plantations (perhaps too much “Gone with the Wind” as a child?). He even owns an armory.

If not for the pandemic, Slonem might be in Latvia, where he has a major exhibition, or Los Angeles, for the installation of his 700-square foot bunny mural—or perhaps he would be visiting one of his three mansions in Louisiana. Instead, he’s cheerfully working away in his Brooklyn studio, where not even Covid can rein in his childlike urge to pull yet another rabbit out of a hat.

Each morning, when he enters his 30,000 square-foot studio, he warms up by painting bunnies, his most consistent subject. Rendered in almost childlike contour lines, his happy, colorful rabbits feel as if they hopped right out of “Alice in Wonderland.”

There is nothing serious about the paintings, no deep message—just fun. The colorful and playful element in his compulsive output and obsessive themes are part of the attraction. “Repetition is divinity,” says Slonem, who turned 70 this week. “Just like the act of repeating a phrase creates a mantra, the act of repeating forms becomes an act of worship.”

Many fans worship at his bird-and-bunny throne. He has achieved cult status among the rich and famous: Julianne Moore, Kate Hudson, the Kardashians all own Slonem originals. He has even appeared on Real Housewives of New York. (episode eight, season 11, if you’re curious.)

Slonem is one of the most prolific, and exhibited, artists working today. His paintings can be found in the permanent collection of over 50 museums around the world, from the Miró Museum in Barcelona and the Moscow Museum of Modern Art to the Guggenheim, Whitney and Metropolitan Museums in New York, to name but a few.

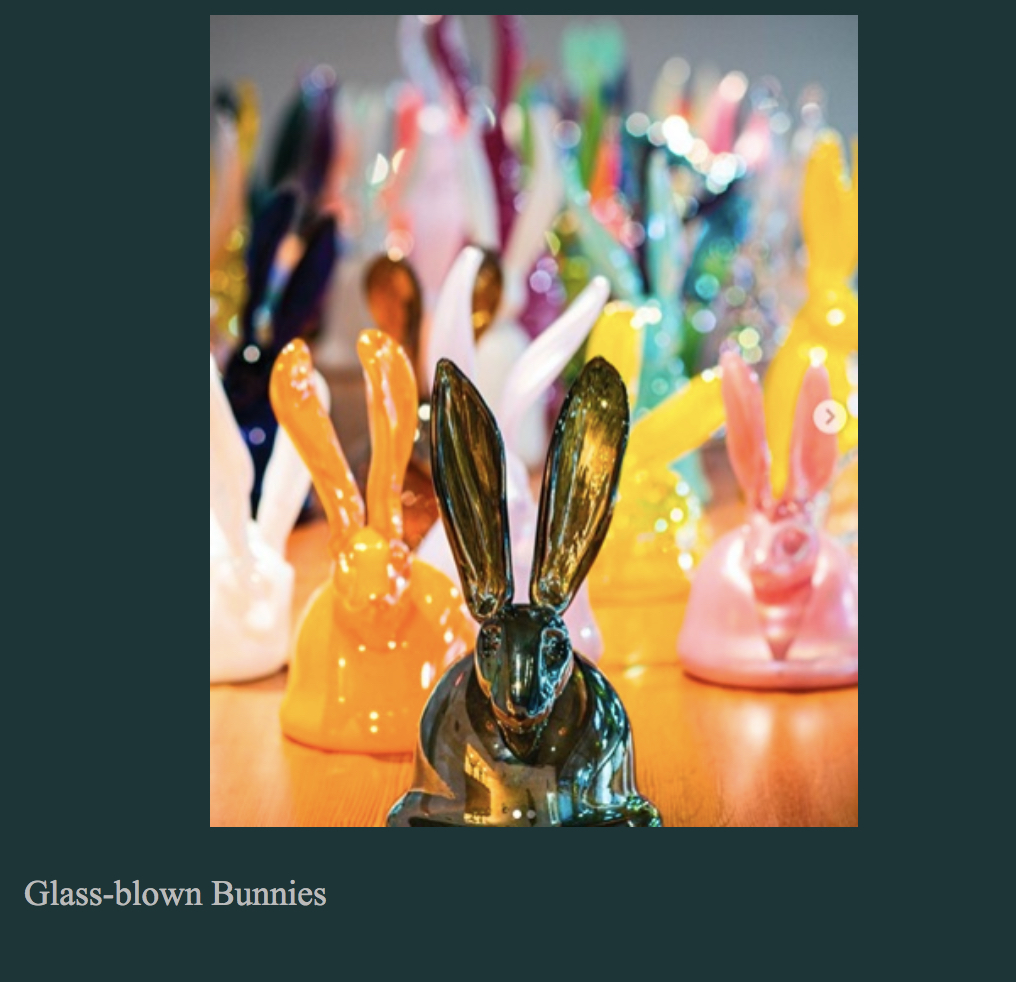

Not content just to have his work hang on a wall, he even has his own “Hop Up Shop” of tabletop items and summer accessories created exclusively for Bergdorf Goodman.

The Hop Up Shop at Bergie’s

All of which invites the question: Why bunnies? “One night I was having Chinese food and I looked down and realized I was the sign of the rabbit,” says Slonem. “Rabbits have a voice and the rabbit family speaks to me. One night my psychic”—Slonem has multiples of these, too—“told me rabbits would take me places nothing else could.”

Then there are the birds, the animals he actually, literally lives with. On any given day a visitor might encounter 70, 80, maybe even 100 of his fine-feathered friends. Unconfined to their cages, these tropical rescue birds (parrots, parakeets, macaws, cockatoos) create a living, chattering mosaic from which he draws inspiration. Constantly in conversation, the birds even speak in multiple languages. “Hello! Let me out of here!” a new arrival once screamed at him—in Spanish.

But back to rabbits.

Working with artisanal glassblowers (virtually these days) at Idlewild Union and Glass Eye Studio in Seattle, he is happily amplifying the personalities of his two-dimensional bunny paintings with three-dimensional form. These glass-blown bunnies are not just wildly colorful; they’re whimsical, improbable, eccentric and so delicious-looking you almost want to pop one in your mouth. “Just like jellybeans,” says Slonem.

While perhaps these jellybeans are not exactly high art, they are pretty crafty.

It’s a whole new world for Slonem. “That’s what is so wonderful about this project. It’s like breaking through a veil of limitation,” he says. “ I’m new at it. It’s exciting. I feel like this is a perfect moment in my life.”

You might also like