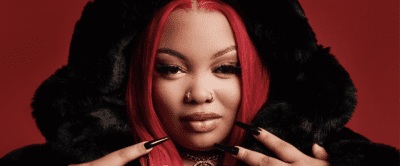

Sharon Jones and the Dap-Kings by deneyterrio is licensed with CC BY 2.0.

When ‘retro’ is an insult: Breaking down the Daptone sound

The author of a new book on the Daptone soul label breaks down the mystique and legacy of the subculture they came to embody

Where Motown and Stax left off, Daptone Records, the independent Bushwick-based funk and soul label, picked up—and pushed forward.

For 20 years, the label, founded by musicians Gabe Roth and Neal Sugarman in 2001, has been churning out juicy soul records from talents such as Sharon Jones and the Dap-Kings, Charles Bradley and many others, while also lending their musical assets to the likes of Amy Winehouse, (whose smash-hit album Back to Black was produced by Mark Ronson at Daptone, using Dap-Kings musicians), Bruno Mars and Lady Gaga. Contemporary rappers have also dug into the Daptone discography—artists like Jay Z, Beyonce, Kanye West, The Black Eyed Peas, and Eminem, among others, have all sampled Daptone music for their own records.

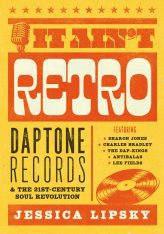

The funk and soul music scene has only grown in the last two decades, even if it was somewhat overshadowed in the mainstream by Top 40 pop and rock. Journalist Jessica Lipsky, a transplant from San Francisco who now lives in Brooklyn, has aimed to settle the matter once and for all with a new book, “It Ain’t Retro: Daptone Records & The 21st-Century Soul Revolution,” which covers the history of Daptone through in-depth interviews with the label’s founders, producers and musicians.

For a list of her five essential Daptone albums, click here.

Brooklyn Magazine recently caught up with Lipsky to discuss the new book and how Daptone Records changed the face of soul music for good.

This interview has been condensed for clarity and length.

The funk and soul scene was always just burbling under the surface in the last two decades. Why do you think it never quite broke through?

It did, eventually. Soul music was sort of like your parents’, there wasn’t a lot that was necessarily happening. And the quote, unquote, traditional style was a thing of subculture. And subculture is not getting reported on. Subculture doesn’t necessarily want to be reported on, it’s not going to be in the mainstream. And in the case of Daptone, who were working really hard, getting attention from a large audience was never really their bag. Obviously they want fans, they want to sell records, but they have this sort of punk rock attitude.

And there was a lot of labeling going on—journalists and fans calling the music “retro” right off the bat. That’s a pretty stifling word to use.

People wanted to use that as an identifier, but didn’t quite understand that this music isn’t a throwback and it’s not trying to imitate. It’s very real, it’s very present. It’s being iterated on in this way. To call it retro is demeaning to passion.

Daptone is an analog studio, which is now a really coveted kind of sound. Did that play a role in Daptone being labeled as “retro?”

Absolutely. Because that’s part of the dominant narrative, right? Like ‘Wow, this label’s like nothing has been changed! It’s basically the same as Whitman from 1974!’ That certainly has always been a part of how Daptone has been covered. Gabe Ross will be like, ‘Yeah, we have great equipment, but for a while, it was just sort of what we could find or what we like. There’s no magic to this room. It just kind of is what it is.’

Sharon Jones is a main character in this book. She was a total superstar on the label—very authentic and purposeful about the music she wanted to put out.

Yeah, absolutely. And that’s what made her performances, in particular, so powerful. There’s a line in the book about how when you went to see Sharon, you felt like you were partying all night with her, and that’s what she wanted too. As somebody who would see Sharon, whenever she came to my town, I definitely felt like that. You felt like she was really herself on stage, the best version of herself. That’s a really, really cool thing to see, and a rare one.

From your reporting, it sounds like the label was really willing to step back and let Sharon do her thing in terms of crafting her sound and making her records.

Yeah. You have a lot of really talented musicians [on Daptone], who maybe started out as not the most talented musicians, but they just had this vibe and were willing to sacrifice their own spotlight to serve the whole. So you have this really, really powerful organism, all playing together, as opposed to having disparate parts.

Speaking of performances, there’s a new live album coming from Daptone later this year. [The Daptone Super Soul Revue Live at the Apollo, which was recorded over three nights in December 2014, is due to arrive October 1st.] Especially after months of lockdown, the live sound is just so sweet.

Yeah, I was still living in California when they had that show. And I remember thinking like, ‘Should I fly out for this?’ and I didn’t, and I deeply regret it!

Was there anything that surprised you when you were writing this book?

The breadth of samples and studio work, and just how far Daptone’s music has gone with other artists. Here I thought it was just, like, Jay Z and a couple other things. I think that really struck me. It forced me to take a bit of a step back and consider that this music has been really effective for a lot of people.

What influence do you think Brooklyn itself had on the label? And is still having on the label?

I think that this city demands a certain level of a musician and a certain commitment as well. The label probably couldn’t be started anywhere else but here. It sounds super romantic, but I think that there’s this grit of life in New York City—it’s not an easy place to be, so if you’re going to start some independent record label, you need to be passionate. And soul music is really good fuel for those passions.

Would soul music be where it is right now without Daptone?

Absolutely not. Daptone is not the only label in the world to have these influences, but I think that they set it foundation. Even if they just helped show other musicians what they really want to do.

You might also like