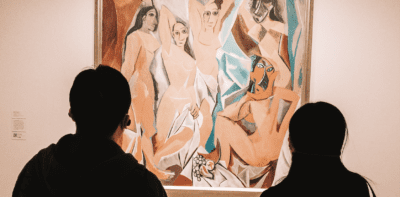

Photo by Carson Crow

A fully naked adaptation of ‘Antigone’ by a Brooklyn troupe comes to the stage

Called 'Antigonick,' the play aims to free and empower the ancient feminist heroine. And yes, everyone gets naked at least once

UPDATE: This story has been updated to reflect the fact that, due to safety concerns, the Torn Out Theater Group has moved the performance to an indoor location. “Antigonick” will no longer be performed in Prospect Park. Instead, it will be performed at The Center at West Park (165 West 86th St in Manhattan), with the following performance times: Friday, August 19, at 8 p.m. and Saturday, August 20, at 3 p.m.

It is a very muggy gray afternoon in Prospect Park, and past the baseball fields, the mini dog beach, the legions of day campers playing dodgeball and stroller-pushing parents, a group of actors is warming up in front of the Music Pagoda, a small performance venue hidden in the park’s lush center.

The actors stretch in a circle then get to work rehearsing “Antigonick,” renowned poet Anne Carson’s darkly humorous reimagining of the ancient Greek tragedy “Antigone,” first published in 2012. They practice an introductory scene with original music that feels demanding in the humidity. So they sit for a water break, discussing staging placements and joking about forgotten lines, all while joggers and dog walkers look on curiously.

“Is anyone allergic to soy?” asks the play’s director Britt Berke, a short and energetic 25-year-old. The fake blood that they will use—in large amounts, owing to the play’s grisly end—will contain soy ingredients.

It’s all a pretty typical scene for an outdoor rehearsal by a small Brooklyn theater group. But one big thing will be different when the show debuts Friday night: All of the actors will be fully naked at some point during the performance.

The adaptation is being produced by the Torn Out Theater group, which has put on multiple past plays with nudity. It was founded in 2016 and aims to “challenge audiences to explore the questions of modern sexuality, gender, and body politics.” The show is free and will be performed just twice, at The Center at West Park (165 West 86th St in Manhattan) Friday, August 19, at 8 p.m. and Saturday, August 20, at 3 p.m.

‘Oh, it’s happening’

Even though the seven actors present only have one naked rehearsal day under their (figurative) belts with just over a week to go before opening night, the mood at rehearsal is relaxed.

“It’s been a beautiful process,” says Sha Batzby, who plays the Messenger and also sings as a member of the Chorus, the group of narrators common in Ancient Greek theater. “It was a big deal in my mind, ‘Oh it’s happening, it’s gonna happen, it’s gonna happen.’ And then once it happened, it just was very freeing and very empowering … There was such hype around it—‘you’re gonna be naked, you’re gonna be naked around strangers.’ Then I was, and I was confident about it.”

Only some of his friends who are coming know that he’s disrobing, however. And he’s keeping it that way.

“I think people come like ‘Oh, they’re gonna be naked!’ and then say ‘Oh, that was beautiful art,’” he says. “It’s like those ‘Simpsons’ ads with ‘Sex! Now that I have your attention, here’s what I was actually trying to tell you.’”

“Antigone,” one of the world’s most performed classic plays, is a classic parable about law and order and martyrdom that has in recent centuries been immortalized as a major political feminist archetype. The titular protagonist, daughter of Oedipus Rex, sacrifices her life to give her rebel brother’s body a proper burial, in defiance of her ruling uncle Kreon’s edict to leave him above ground for the vultures.

Carson’s “Antigonick” is a playful, hyper-aware 21st-century version of the play. It keeps the dark original story intact but adds asides that break the fourth wall and plenty of poetry. For example, Kreon at one point says he prefers verbs to nouns. Eurydike, Kreon’s wife, says “this is Eurydike’s monologue/it’s her only speech in the play.” Most of the chorus’ lines are turned into poems.

(The “nick” in the title refers to the “nick of time,” a concept that comes up repeatedly, and to a character named Nick that Carson has added in and whose one stage direction is: “always onstage, he measures things.” Even Berke admits the character is a struggle to understand and incorporate on stage.)

Carson’s text doesn’t call for any nudity, but Berke, intimacy coordinator Cristina “Cha” Ramos and others on the creative team spent a lot of time working the concept into the text, for multiple reasons. Each character gets naked at different moments in the play, symbolizing developments in their points of view on Antigone, who is nude for the longest amount of time.

At multiple moments in her text, Carson mentions Bertolt Brecht’s version of the play, set during World War II. His Antigone character walks around the stage with a literal door strapped to her back, encapsulating the cumbersome metaphysical burdens she is weighed down by in her oppressive society. The nudity, Berke says, acts as a kind of foil to the Brechtian version—by shedding her clothes, Antigone makes a statement about shedding expectations and her adherence to the laws of Ancient Thebes, under which women have little say.

The nudity also fits in Berke’s eyes because she says the play (both the ancient and Carson versions) is at its core about the importance of sanctifying the body. Antigone is not only on a quest to protect her brother’s body; she is also afraid that leaving it above ground will upset the gods and meddle with the order of her family’s entire world.

Nudity as protest

Ramos sees Antigone’s nudity as an act of protest—one meant to make the ruling alpha male Kreon, fully clothed for most of the play, physically uncomfortable. Especially when Antigone first gets naked in front of him.

“She’s sort of paradoxically the most vulnerable person on the stage at that moment. But it belongs to her. And it makes him uncomfortable, how much she is owning her body and owning the space in that way,” Ramos says. “And so there’s definitely an in-your-face-ness about it towards the character of Kreon.”

Ramos has worked as both a fight and intimacy coordinator on other stage productions that involved nudity, but admittedly none that involve as much as this “Antigonick.” She says the sheer amount of nudity actually lets it add to the art—not just to quick moments of shock value.

“This show has given me this understanding that nudity is so often either sensational or sexual. And that to go a different way is so unique in our culture. It really kind of throws the lid off of a lot of things,” she says. “So we’ve been discovering lines in this piece that have so much more depth because the actor saying them is nude.”

She finds especially poignant the moment at the end when Kreon finally gets naked—it’s the ultimate way to hammer home the “too little, too late” idea (spoiler alert: multiple members of his family kill themselves).

Berke also found resonance in the idea of showcasing nudity coming out of the Covid-19 pandemic, which kept our bodies inside for such a long stretch of time.

“After this weird, lonely year where we’ve literally had to isolate and disconnect from people to be safe, it’s really important to do theater that’s about the importance of touch and the importance of connection,” she says. “Everyone is like, ‘Oh, it’s so awkward to have social interactions now.’ And it’s like, okay, what if we cut that narrative? And what if we were naked? Like, what if all those barriers were down? What does it mean to actually experience our bodies again, after having to keep them private for so long?”

You might also like