People of my shtetl Berla Klein, Plaster (Shtetl Art Gallery)

Inside the new Hasidic art gallery that just opened in Williamsburg

Shtetl Art Gallery is a first in the borough, dedicated to works of art by Hasidic artists

It almost sounds like an oxymoron: Shtetl Art Gallery is the first Hasidic fine art exhibition space, smack-dab in the middle of Williamsburg. And yet, somehow it works. According to owners Zalmen and Leah Glauber, who have been married for 27 years, Shtetl might actually be the very first art gallery of its kind in the world.

Housed in the basement of the Condor Hotel on Franklin Avenue, which Glauber happens to co-own, Shtetl opened back in July, exhibiting art either made by or about Hasidim, members of the strictest sect of the orthodox Jewish faith.

“For me, art was always a form of storytelling,” says Zalman Glauber. “It has to have a philosophical message and since I started working on my own art, I started appreciating different forms of it. So, if we find a secular person that wants to display something about Hasidim that I find interesting, we’ll do it.”

Currently featured artists include Lipa Schmeltzer, a widely known Jewish American singer, entertainer and composer; Miriam Lefkovits, who is Glauber’s mother, and Glauber himself, who focuses on sculptures.

“I started playing around with miniature figures years ago,” the gallery owner remembers, also mentioning the dioramas he works on yearly to decorate his sukkah, the temporary huts that Jews traditionally spend time in during the one-week-long holiday of Sukkot. “During a break in my semester in school, I took a sculpting class.” It stuck.

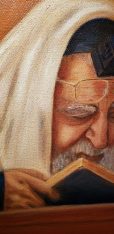

Rav Ovad Yosef, Oil on Canvas (Shtetl Art Gallery)

Due diligence

Given the stringency of the Jewish laws that dictate many aspects of a congregant’s lifestyle, Glauber felt compelled to run his new passion by a rabbi before completely diving into it.

“I actually sat down with three different rabbis to ask what is allowed and what isn’t,” he recalls. “Everyone came to the same conclusion: if I wasn’t sculpting a person fully whole—if the sculpture was somehow blemished, with nine toes for example—then it was okay.”

The criteria, which is based on Judaism’s prohibition of idolatry, ended up becoming the artist’s most recognizable trait, in a way. “When I was in school, I did a sculpture of a man and one of the ears wasn’t whole,” says Glauber. “The teacher asked me why I didn’t finish it and I explained about idolatry. He told me it was going to become my signature.”

Although clearly focusing on Judaism, Glauber and his wife Leah, the gallery’s director, hope to attract all sorts of visitors, both of the religious and secular kind. The couple acknowledges that shows like “My Unorthodox Life” on Netflix have recently shed a negative light on the Hasidic community, including the nearly 60,000 members that call Williamsburg home, and believe that Shtetl can help remedy that by proving that religious Jews aren’t insulated from the world at large and can appreciate forms of entertainment, like art, that might at first glance seem to be at odds with a devoutly spiritual lifestyle.

“If we look back at Jewish history, art was there and was always an important aspect,” says Glauber. “Art is a way of preserving and telling the story, of sending a message. If it was important enough to be part of the Torah—when God told Moses to go find a guy that will help him build a menorah and decorate the Beit Hamikdash [ancient temple]—then [it should be important now].”

That being said, Glauber understands how out-of-the-ordinary his endeavor is. “In this community, the idea of having an art gallery or selling art [isn’t common],” he says. That unconventionality is exactly what he hopes will make a difference and bridge the gap between the Hasidic community and the rest of the world, especially in an era in which folks are craving cultural pursuits of all kinds.

As for future plans, Glauber wishes for more of the same in order to actually make a difference. “Someone asked me if the idea here is to get so big that we move to Manhattan,” he says. “And I said, ‘No, we’re staying here. That’s the point’.”

You might also like