Installation view, Baseera Khan: I Am an Archive, Brooklyn Museum, October 1, 2021–July 10, 2022. (Photo: Jonathan Dorado)

Baseera Khan gives us a tour of their Brooklyn Museum solo show

Khan’s ‘I Am an Archive,’ a bold multidisciplinary exhibition, investigates surveillance, cultural exploitation and xenophobia

Baseera Khan’s latest exhibition kicks off with a striking self-portrait.

“As you enter the space, you see an archive of my body,” the artist tells a buzzing crowd of museum-goers that have flocked to the exhibition to hear Khan speak. “I used 3D body-scanning technology to create it.”

“Bust of Canons,” one of 11 new artworks created for Khan’s “I Am an Archive” show at Brooklyn Museum, is a 3D-printed replica of the artist’s head and torso. Khan’s bust is locked in a dramatically contorted pose, and a speaker is embedded in their chest (pictured above). As Khan describes it, the bust’s twisted stance references the “S-Curve” poses often found in idealized temple sculptures of Hindu goddesses and deities, specifically the Yakshi sculpture.

Khan’s own voice emanates from the speaker; the artist produced a full-length album for the installation with the help of musicians Kaia Fischer and Stuart Gunter. The music rings throughout the gallery, lamenting the impossibility of love and desire.

The bust is also topped with a lock of Khan’s hair.

“I am really uncomfortable with static sculptures. I wanted there to be some kind of performativity to the piece,” says Khan, pulling the hair from a socket in the bust’s head to show the crowd. “I am planning over the course of the year to make paintings with this hair.”

Curated by Carmen Hermo, associate curator at the Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Artis, “I Am an Archive” is Khan’s first solo museum exhibition, presented as part of the annual UOVO Prize for an emerging Brooklyn-based artist. As part of the award, Khan was commissioned to install a 50-by-50-foot mural on the facade of UOVO’s Bushwick facility.

Khan has spent the past decade living in Crown Heights and turning heads in the contemporary art scene. Originally from Texas, the artist explores the realities of growing up Muslim in America, and unmasks the xenophobia and surveillance that plague our cultural landscape. In “I Am an Archive”, Khan visualizes their body as a site of history and trauma, but also as a tool for liberation. Through sculpture, collage, photography, textile, drawing, and video, Khan documents their life and presents a “counter archive” to the skewed narratives of imperialism.

Khan has shown in cities from Munich to New Orleans and contributed to permanent collections in Kadist, the Guggenheim, and Walker Art Center. Their Brooklyn Museum debut includes both new artworks and key pieces made since 2017.

Among the new works are four glimmering chandeliers. The sculptures are suspended from the ceiling by revolving disco ball motors, and refract shards of blue light along the walls. Each chandelier is based on patterns from Khan’s family archive of traditional textiles and embroidery designs.

Khan leads the crowd to their “Laws of Antiquities” photographs. In this new series, the artist staged intimate portraits with objects from the Brooklyn Museum’s Arts of the Islamic World collection. To make it happen, Khan worked around exhaustive rules set out by museum conservators, sometimes creating mischievous loopholes to pose with more fragile relics.

In one of the photographs, Khan peers from behind a printed facsimile of a seventeenth century Iranian prayer rug. The gloved hands of a conservator—a recurring image in the series—hold up a fourteenth century mosque lamp.

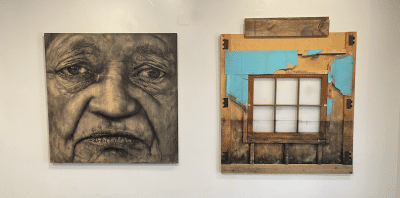

Installation view, Baseera Khan: I Am an Archive (Photo: Jonathan Dorado)

The title of the project refers to the conservators’ restrictions, but also to the history of global regulations that preserve and displace cultural artifacts. By collaging geographically disparate objects, Khan points to the Eurocentric notion of the “Islamic World” propagated by Western museums.

“I work in a paradox,” Khan says. “A situation of both exile and kinship. In this conflict I find joy in being intimate with objects that are rarely accessible to most people, but always feel in that experience a reverence in exposing its colonial and occupational histories.”

A recording of Khan’s ongoing and best-known performance piece, “Braidrage,” is projected on a wall in the final room of the exhibition. In the film, Khan douses their limbs in black chalk and scales a rock-climbing wall made from ninety-nine resin casts of their own body. A massive braid, woven from both real and synthetic hair imported from India, looms in the foreground of Khan’s ascent. That same braid hangs in the Brooklyn exhibition space.

“Braidrage” is an essential ritual in Khan’s artistic practice and a direct confrontation with personal and imperialist traumas.

“The work came together after several infuriating situations in my life,” Khan says in an interview with ArtAsiaPacific. “I was left with nothing more than instinct to move past the hard times, and rage. Rage protects my softness when softness is not an option.”

‘Braidrage,’ Baseera Khan: I Am an Archive (Photo: Jonathan Dorado)

“I Am an Archive” resides in the Brooklyn Museum Sackler Center and rubs shoulders with “The Dinner Party,” Judy Chicago’s iconic feminist banquet.

“I couldn’t really show my art without thinking about ‘The Dinner Party’,” Khan tells the audience as the tour draws to a close. “Just like ‘The Dinner Party’ comes together thinking about all of these phenomenal, femme figures, I think about ‘Braidrage’ as a collective self. A collective power of people climbing as high as they can with endurance.”

“I Am an Archive” is on view through July, 2022.

You might also like