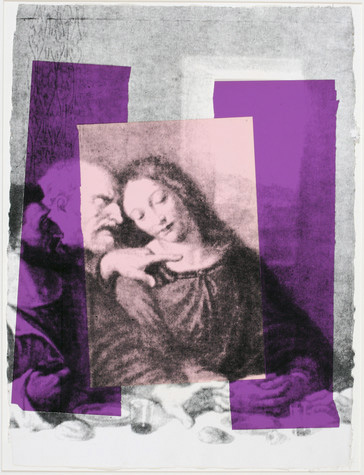

Detail of 'The Last Supper,' 1986 (The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc.)

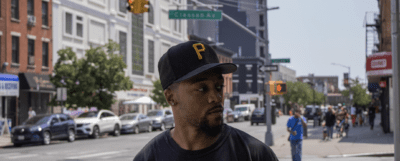

Andy Warhol comes to the city of churches

From Catholicism to Campbell’s to camp and soft-core, a new exhibit at the Brooklyn Museum takes a fresh look at a modern master

“Lord make me chaste, but not just yet.” St Augustine’s wayward prayer could just as easily have been uttered by Andy Warhol.

As surprising as it may sound today, Warhol was one of the most religious of all modern artists. Throughout his life he embraced his Catholic upbringing, while also unabashedly embracing his homosexuality.

“Church is a fun place to go,” Warhol once said. “The church I go to is a pretty church. They have so many masses.” He went on to admit that sometimes he took communion even though: “I never feel that I do anything bad.”

An ambitious, eye-popping exhibition titled: “Andy Warhol: Revelation” will debut at The Brooklyn Museum on November 19. This radically original show will be the first of its kind to explore the conflict between Warhol’s Byzantine Catholic faith and his homosexuality. On display will be a profusion of more than 100 objects, offering visitors an unexpected perspective on the artist’s complex relationship between conspicuous consumption and religious devotion.

With his pale, blotchy complexion and wild silver fright wigs, Warhol was as recognizable as his pop images of Campbell’s soup cans, green Coca-Cola bottles, Marilyn Monroe diptychs, Brillo boxes, Elvis Presley and Elizabeth Taylor—images that have been silk-screened ad nauseam into our consciousness.

Obsessed with celebrity and money, he courted the rich and famous, lived openly as a gay man before the gay revolution movement, surrounded himself with drag queens and drug addicts and hired hot young men to pose for his “porno-nudes.” Therefore, it must have come as quite a shock when, in 1987, at his memorial service at St. Patrick’s Cathedral, the great British art historian and Picasso biographer, John Richardson, outed Warhol as a life-long closeted, church-going Catholic.

“I’m not afraid to die,” Warhol once said, “I just don’t want to be there when it happens.”

In the eulogy Richardson gave to the 2,000 attendees that day, he shared a side of Warhol that had been hidden from all but his closest friends: his spiritual side.“Those of you who knew him in circumstances that were the antithesis of spiritual may be surprised that such a side existed. But exist it did, and it is key to the artist’s psyche. Warhol,” Richardson continued, “took considerable pride in financing his nephew’s studies for the priesthood. And he regularly helped out at a shelter serving meals to the homeless and hungry.”

According to Warhol’s biographer, Blake Gopnik, “references to his religion are plentiful in his diaries, even though they were rare, and tentative, during his lifetime.” But to his many Catholic friends, his religious side was not so secretive. In fact, the majority of his inner circle were Catholics. “He may have related better to us Catholics because we all have the same background: Mass, priests, nuns, Catholic school,” wrote photographer and artist Christopher Makos in the preface to his book, “Lady Warhol.”

“For Andy, and others like me,” recalls Penny Arcade, performer, writer and star of Warhol’s “Women in Revolt,” “our first taste of stardom were the portraits and statues of Catholic saints in our childhoods. They were the first superstars. We all transitioned from saints to movie stars. In the years I knew Andy,” Arcade continues, “while his mother was alive [1969 to mid-1972], he accompanied her to Mass every morning. Andy and his business manager and co-director, Irish-Catholic Bostonian Paul Morrissey, dripped Catholic guilt. Together they were like two defrocked Catholic priests.”

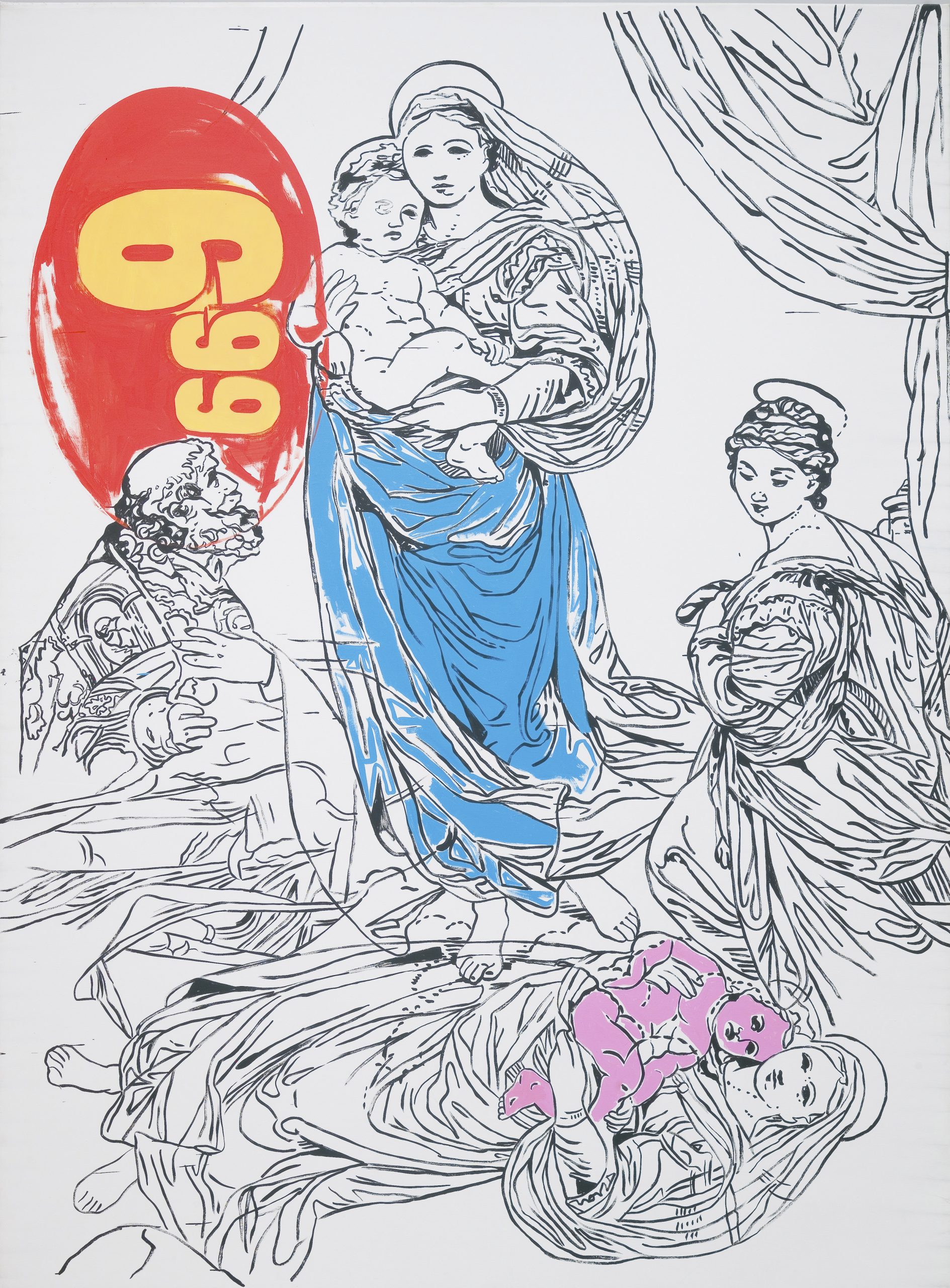

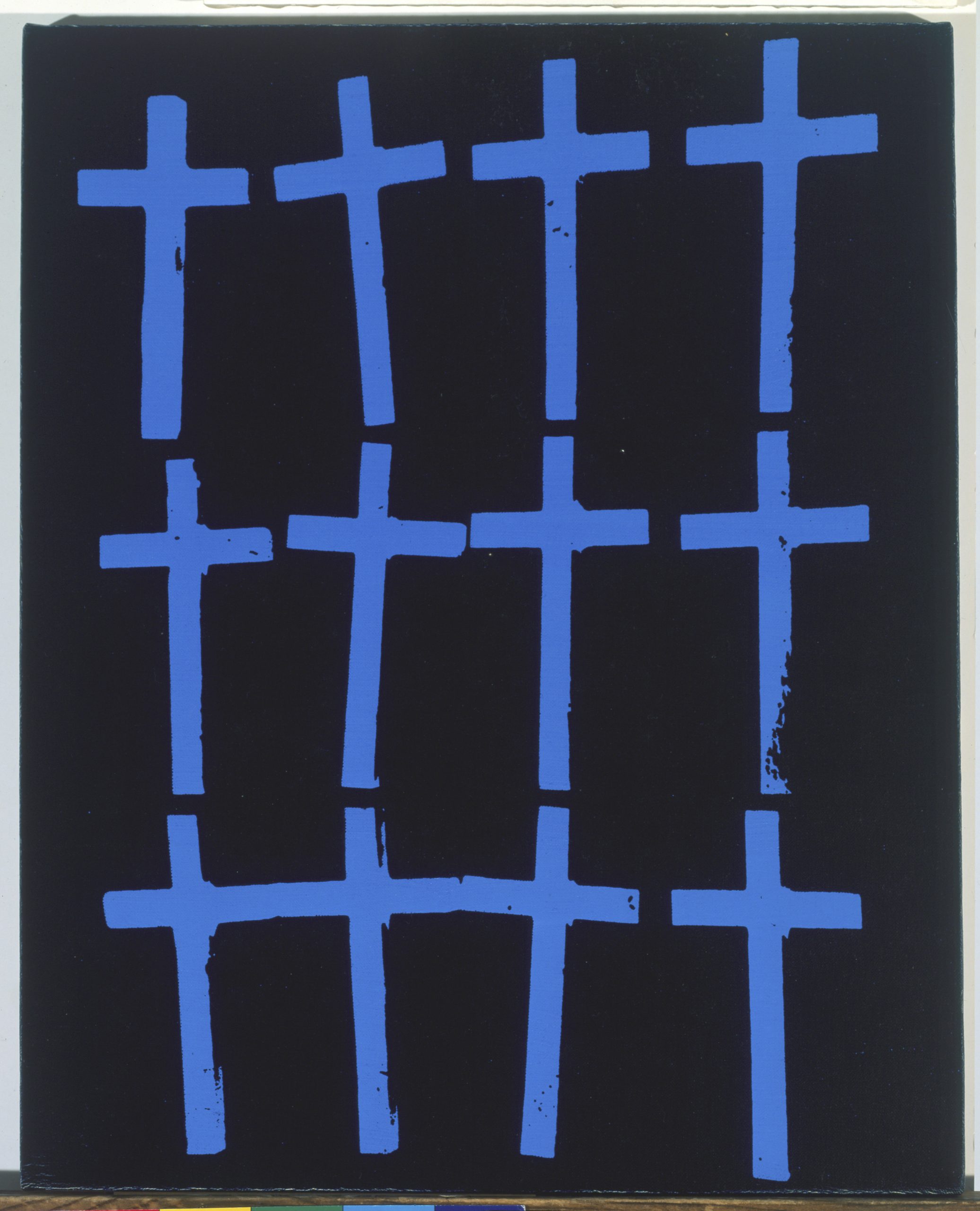

Beginning with Warhol’s very first known religious painting, a Jesus statue, lovingly rendered on plaster, and dated 1938-’41, when he was around 10 years old, and ending with two large paintings from his final work, “The Last Supper,” based on Leonardo da Vinci’s masterpiece, the Brooklyn Museum exhibit is one with a totally unique premise: Among the many bombshell revelations, visitors will be surprised to learn how the Catholic themes that appear throughout Warhol’s entire career really intersect with Warhol as we know him.

‘The Last Supper’ (Detail)

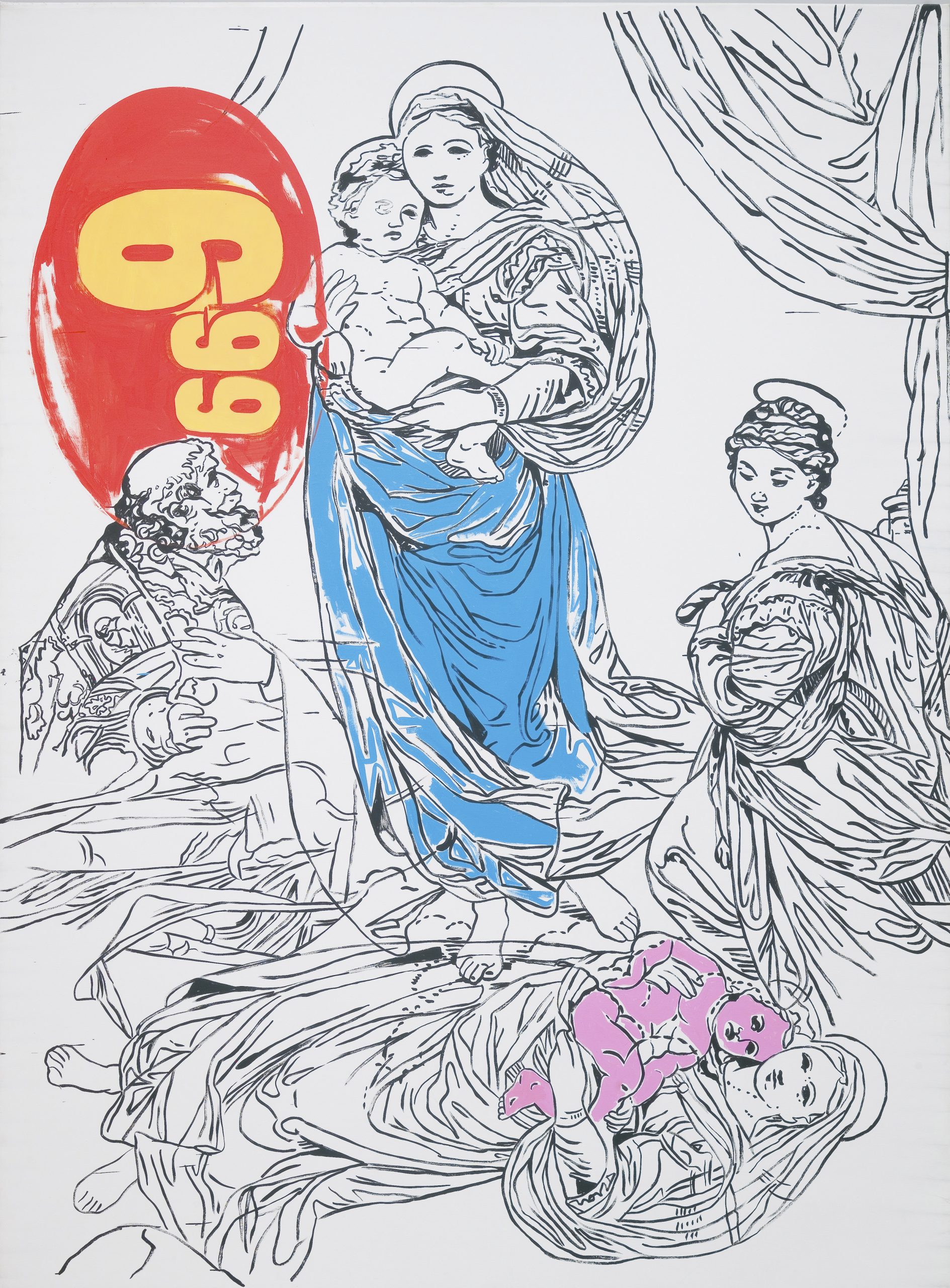

“From the sex, drugs and rock and roll of ‘The Chelsea Girls,’ to his riffing on Renaissance masterpieces, to his early works of queer desire and his exploration of death, there’s a current of love for Catholic ritual and imagery.” says associate curator Carmen Hermo.

Adding to the exhibition is a section on Warhol’s collaborations with younger artists such as Jean-Michel Basquiat. Included will be an installation piece of 10 body-size punching bags in a row with Jesus’s face on each one of them. In his exhaustive—and exhausting—biography of Warhol, Gopnik writes that by placing Jesus on punching bags, “it seems like an invitation to sock it to the Savior—closer to sacrilege than to worship.”

Another section will feature newly discovered items such as the original encyclopedia source for his epic “Last Supper” series, plus ephemera from his baptism, his audience with the Pope and his two separate funerals, one in New York and the other in Pittsburgh. Better still, there will be a fantastic constellation of works by his mother, self-taught Julia Warhola, including her drawings of angels and cats. “She is known for providing the penmanship seen in many of Warhol’s early works,” says Hermo. “Her care for her creative child—and two decades spent living with him as an adult in NYC—indelibly shaped him as an artist, but also sustained his religious devotions, as they prayed together every day before he left for the studio!”

Beyond his mother, an entire section of the exhibition will be devoted to Warhol’s women, some of whom he elevated to iconic status including Monroe and Jackie Kennedy. “Just as Catholic art makes use of metaphor and allegory, Warhol transformed the lives of real women into metaphors for tragic beauty and the beauty of tragedy,” says Hermo. Indeed, half of Warhol’s “Superstars” were women: Candy Darling, Carroll Baker, Viva, Edie Sedgwick, Brigid Berlin, Ultra Violet, to name a few.

Creating contrast, there will be a section of images celebrating nude male bodies and exploring queer themes. “Some of the first works Warhol sought to exhibit when transitioning from commercial material to so-called fine art were of nude men,” says Hermo.

“Nothing enhances decadence like Catholic guilt,” posits Penny Arcade.

Raphael Madonna-$6.99 (1985)

‘Success is a job in New York’

Andrew Warhola was born on August 6, 1928, in Pittsburgh. His parents, Andrej and Julia, were devout Byzantine Catholics who had immigrated from eastern Slovakia in the early 1920s. Andrej was a construction worker, while Julia was a domestic with a strong, artistic bent. She enjoyed embroidering, drawing and decorating their home with icons, holy cards and hand-painted Easter eggs. She would also arrange artificial flowers in coffee cans, cover them with foil and go door-to-door selling them. She was to become her son’s greatest influence, even collaborating with him in later years.

Every Sunday the family walked more than a mile to pray at their local Byzantine Catholic Church. Here Warhol would stare for hours at the icon paintings of Christ and the saints that hung in the iconostasis, or icon screen, at the front of the nave.

His relationship with the visual image was, no doubt, formed during this church-going youth, where later in life he would replace religious icons with product logos and the saints with celebrities.

But Warhol was a sickly child, plagued by various health disorders. At the age of 8, he contracted chorea—also known as St. Vitus’ Dance—a rare and sometimes fatal disease of the nervous system that left him bedridden for several months.

In addition to his physical illnesses, he was plagued by bad blotchy skin, which started to lose pigment. Some people called him “Spot” or “Andy the Red-Nosed Warhola.”

During these months, while sick in bed, Julia showered him with attention, cutting out paper dolls to amuse him and giving him his first drawing lessons. Drawing soon became Warhol’s favorite childhood pastime. Throughout these long bed-ridden periods, he would listen to the radio and collect movie magazines, the start of his lifelong obsession with Hollywood celebrities and fame.

Growing up in a house without books, everything he learned was visual: “I never read,” Warhol once said, “I just looked at pictures.”

He also fell in love with movies. His early ambition was to become a projectionist, so Julia saved $9 and bought him a projector where he showed cartoons on a wall in the apartment.

“Before I thought it would be fun to be dead. Now I know it’s fun to be alive.”

In 1949 Warhol graduated from Carnegie Institute of Technology (now Carnegie Mellon University). hopped a Greyhound bus for New York and dropped the “a” from Warhola. Three years later, in 1952, Julia followed him. They lived together until 1970. (Warhol’s father died when the artist was just 13.)

Warhol had no trouble finding work as a commercial illustrator. His first project was for Glamour magazine for an article entitled, “Success Is a Job in New York.” Throughout the 1950s Warhol worked as a commercial illustrator for such magazines as Vogue, Harper’s Bazaar and The New Yorker. He also produced advertising and window displays for local New York retailers. His work for the shoe company I. Miller won him awards from the Art Director’s Club and the American Institute of Graphic Arts.

By the time he was 27 he was one of the most sought-after commercial illustrators of the day, earning more than $100,000 a year—a sum that in 1959 would be worth nearly nine times as much today. In 1952 Warhol had his first one-man show at the Hugo Gallery in New York. The exhibition was titled, “Fifteen Drawings Based on the Writings of Truman Capote.” (Twenty years later, the artist and the writer began recording dozens of hours of their conversations with the idea of using them as the springboard for seven Broadway plays about gay cosmonauts. It never happened.)

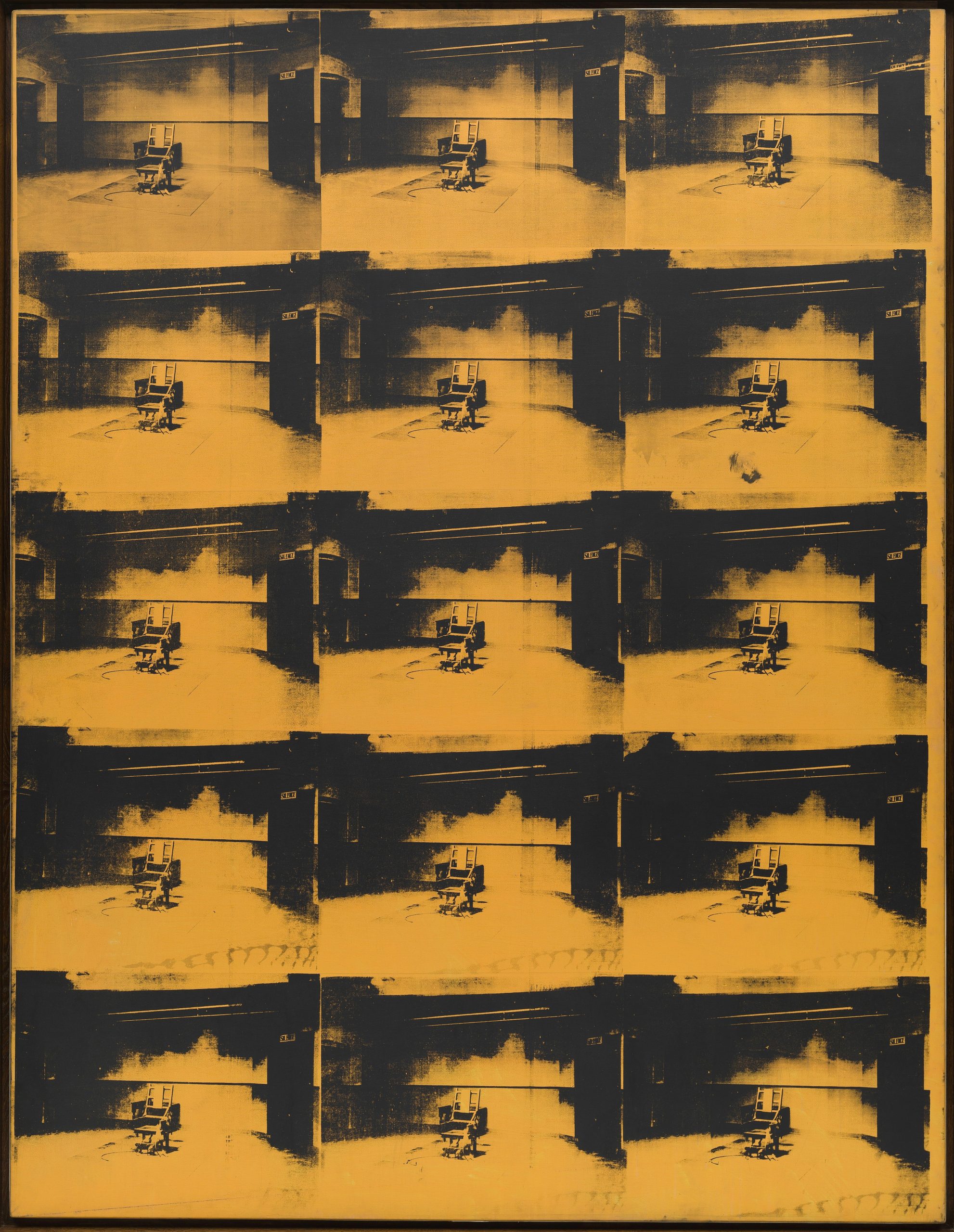

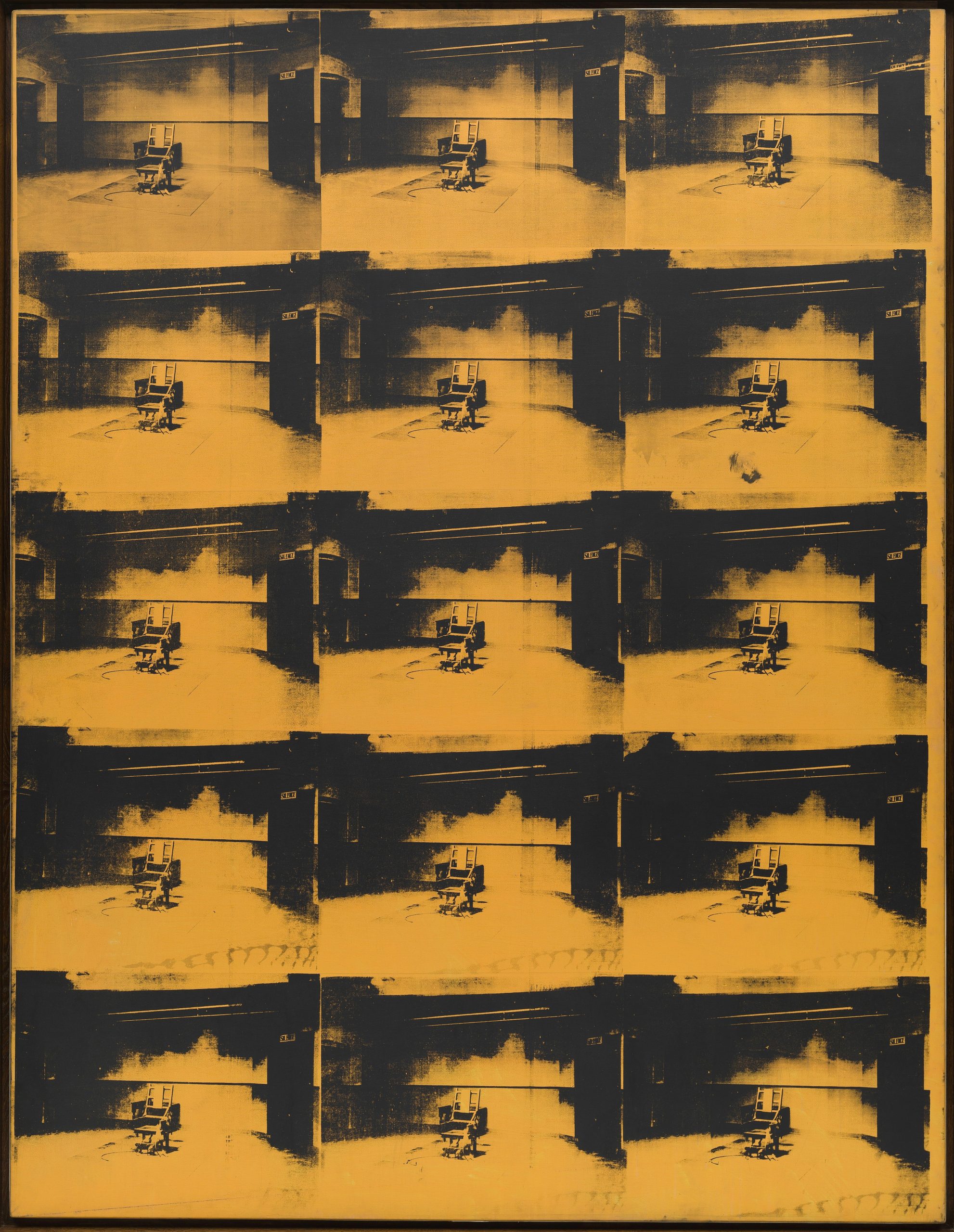

In the early 1960s Warhol began what would become his most astonishing, epoch-making work: silk-screening everyday objects such as Campbell’s Soup cans and Coca-Cola bottles and celebrities like Monroe, Presley, Taylor and Kennedy. “He was a genuinely true visionary. He really understood media … he understood what people, icons, mean,” says Vincent Fremont, former executive manager of Warhol’s Factory and vice president of Warhol Enterprises Inc.

Not only was Warhol depicting mass products, he wanted to mass produce them. So in 1962, he moved into a vast headquarters, a former hat manufacturing facility that famously became known as the Factory.

In addition to being an art-producing machine, the Factory also became a film studio as well as a melting pot for an assortment of celebrities, rock stars, drag queens, drug-addicts and social misfits.

‘Orange Disaster #5,’ 1963 (The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc.)

‘His name was magic’

The films produced at the Factory were usually made up of improvised dialogue, a lack of plot and plenty of commercial sexploitation. “My movies may have looked like home movies,” Warhol once said, “but then our home wasn’t like anybody else’s.”

Legendary actress Carroll Baker, who sizzled up the screen in Tennessee Williams’ “Baby Doll,” remembers Warhol fondly as a pal, not at all like the persona he adopted for the media. She should know: Baker starred in Warhol’s very vile and very funny final film, “BAD,” in which she played a woman who operates two businesses: electrolysis and murder for hire.

“Andy was a very good friend, nothing like the image he presented. He was the sweetest, mildest, kindest, most wonderful person you could ever want to meet,” Baker tells Brooklyn Magazine.

“I was living in Rome when we met. When he invited me to star in ‘BAD,’ I jumped at the chance because he was so big at the box office in Italy I knew it would be great for my career. His name was magic. The Italians loved his movies. I wanted to do the film so badly that when the actor Perry King was fighting for first billing, I told my agent to give him half my salary and let him take second billing!”

In all, Warhol made over 650 films including “The Chelsea Girls,” “Lonesome Cowboys,” “Trash,” “My Hustler” (his social comedy about gay life), his fabled eight-hour epic “Empire,” and his unfinished film, “Sunset,” a section of which will be shown as part of the exhibition. Commissioned in 1967 by Catholic art collectors John and Dominique de Menil to create a film with spiritual significance, “Sunset” is a meditation on the temporality of an everyday phenomenon. The “Sunset” project was funded by the Catholic Church specifically for the Vatican pavilion at the 1968 world’s fair in San Antonio, Texas, but the project was never realized.

Warhol shot a portion of the film from the de Menil Foundation’s founding director Simone Swan’s Fifth Avenue apartment window, which overlooked the Central Park Reservoir. When I spoke with Swan from her home in Tucson, Arizona, she told me that, “In 1974 Warhol approached me to instill narration, or attempt to, into his future films. After a few tentative sessions with his group in the Factory I bowed out. I was then a working mother raising two young children, while Andy’s cohorts were a group on drugs with tendencies to swear or to remove their pants. With me Andy was super courteous, treating me as if he were a student in Catholic school speaking with Mother Superior.”

‘Fun to be alive’

Warhol’s religion became ever more pronounced after a brush with death. The fact that he survived at all is in itself a miracle.

On June 3, 1968, a radical feminist writer and bit player in the Factory universe, Valerie Solanas, took the elevator to the sixth floor office at 33 Union Square West armed with two guns and a grudge. A few minutes after entering Warhol’s studio she shot at him—three times. Two shots missed, but the third one punctured his lungs, liver and esophagus. “It felt like a cherry bomb exploding inside me,” he later recalled. Solanas’ motive was as outlandish as the act it inspired: She had written a play called “Up Your Ass” that she believed Warhol would produce. But even for Warhol, whose films were frequently shut down by the police for obscenity, the play was too far out, too obscene.

The injuries from the shooting were severe. Warhol was clinically dead for a minute and a half before doctors were able to revive him. He then spent the next five and a half hours on the operating table where his spleen was removed and then the next two months in the hospital recuperating. For the remainder of his life he wore a surgical corset, dyed of course in pretty colors.

Warhol summed up the experience in his typical fashion: “Before I thought it would be fun to be dead. Now I know it’s fun to be alive.”

Writing in her memoir, “After Andy: Adventures in Warhol Land,” Natasha Fraser-Cavassoni, the last employee hired at the Factory, described the shooting as “a pivotal moment: Andy changed. He almost died. Then rose again—somewhat symbolic.”

The incident left him terrified of hospitals, so much so that when, a few years later, he was diagnosed with a serious gallbladder infection, he refused surgery. But by 1987, in terrible pain, he could no longer postpone treatment.

On February 20, Andy Warhol entered New York Hospital for what was assumed would be “routine surgery.” When the surgeons pulled out his gallbladder, they found it riddled with gangrene. “I’m not afraid to die,” Andy once said, “I just don’t want to be there when it happens.”

Warhol died of a heart attack the next morning. His second death. He was 58.

In the last 10 years of the artist’s life, religion had become ever more important. The very last work he created before he died was the most ambitious of his life, a monumental cycle of 100 paintings and drawings of “The Last Supper” based on Leonardo da Vinci’s masterpiece, two of which you can see when you visit the Brooklyn Museum’s “Andy Warhol: Revelation.”

“The idea is not to live forever,” Warhol once said. “It is to create something that will.”

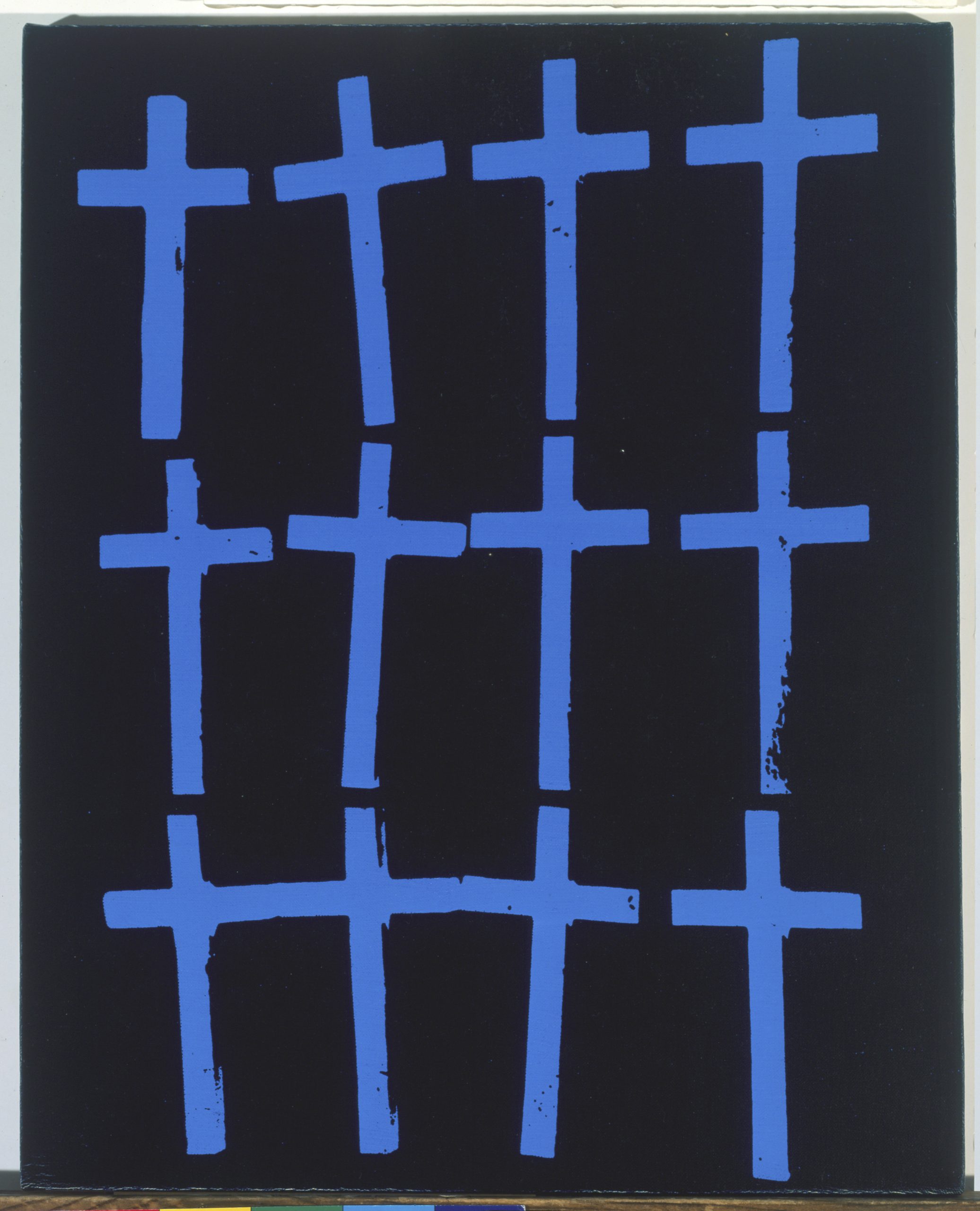

‘Crosses,’ 1981-82 (The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc.)

Andy Warhol: Revelation is organized by the Andy Warhol Museum and curated by José Carlos Diaz, chief curator.

The Brooklyn presentation is organized by Carmen Hermo, associate curator, Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art, Brooklyn Museum.

Exhibit information

Andy Warhol: Revelation

November 19, 1921 – June 19, 2022

Brooklyn Museum Morris A. and Meyer Schapiro Wing and Iris and B. Gerald Cantor Gallery, 5th Floor

Tickets are now on sale. Because of capacity restrictions due to covid, all visitors must have a timed ticket.

Films shown in the exhibit:

A 15-minute excerpt of “Sunset,” Warhol’s unfinished film, will be looping all day, every day, inside the galleries. The film was originally commissioned by the de Menil family and funded by the Roman Catholic Church. It includes a soundtrack by Warhol superstar Nico.

“The Chelsea Girls,” Warhol’s 1966 three and a half-hour, shocking, art house classic will screen twice daily. This experimental underground film stars Nico and a cast of Factory characters. When the film was shown in 1967 in Chicago, critic Roger Ebert wrote: “we have here a split-screen improvisation … employing perversion.”

This article first appeared in the Fall 2021 issue of Brooklyn Magazine. Click here to subscribe today.

You might also like