Linnell, left, and Flansburgh (Photo: Shervin Lainez)

They Might be Giants turn 40 with a new album, an art book and a tour

Four decades in, the duo remains the undisputed masters of alt-rock weirdness. Just don’t try to read too deeply into them

“BOOK,” the 23rd album from They Might Be Giants, opens with, of all things, a kind of a press conference.

In the opening track, “Synopsis for Latecomers,” John Linnell invokes a PR flack trying to explain away a series of increasingly ridiculous mishaps—a cargo ship found abandoned in the desert, a haunted forest, a volcano emerging beneath the city—that start to feel uncomfortably close to our own news cycles. “You’ll get your answers,” he waves us off, “all in due time.”

Linnell and his musical better half, John Flansburgh, have never been about easy answers. As the venerable Brooklyn alt-rock band They Might Be Giants, they write songs that are by turns surreal, funny, challenging, impressionistic—and if you look too close, deeply melancholy. You have to laugh at They Might Be Giants songs, or else you’d cry.

Maybe it took the past WTF year-and-a-half of disasters to put their brand of reality-bending weirdness into perspective for listeners. But one gets the sense that, although the momentum of their current project may have been blunted by the Covid pandemic, Flansburgh and Linnell’s enthusiasm for the craft is as powerful as ever.

“If you ever really want to get in touch with mortality, be in a rock band for 35 years,” Flansburgh jokes. “Keeping things interesting is a big creative and physical challenge. It’s taken over our lives in every way imaginable, so it’s important to keep it exciting.”

Now older and wiser—both are now in their 60s—and perhaps getting a little restless, they’ve stopped worrying so much about how people see them and are focused on pushing musical boundaries while maintaining that inimitable alchemy of “pop” and “weird.” (Need a primer? Click here for a TMBG playlist for fans and newbies alike.)

Don’t let’s start

It’s been almost 40 years since their first gig, at a 1982 Sandinista rally in Central Park. Friends since high school in Lincoln, Massachusetts, Flansburgh and Linnell reconnected in Brooklyn, where they moved in 1981 after college. They started out playing small shows, just the two of them, an accordion and a drum machine, and became a key part of the eccentric DIY music scene in 1980s New York City. When a broken wrist for Linnell and a burgled apartment for Flansburgh left them unable to play live shows for a bit, they began recording demos that fans—or maybe curious potential fans, as their typical show attendance at the time was around 35 people—could call in and listen to as an outgoing message. Dial-A-Song quickly became legendary among New Yorkers of a certain age (and parents of out-of-area fans hit with unexpected long-distance phone bills).

In 1990, “Flood” took the band mainstream. Quirky, upbeat songs like “Birdhouse in Your Soul” and “Particle Man”—and the irresistible cover tune “Istanbul (Not Constantinople)”—are burned into the collective Gen X consciousness, and it’s easy to forget the band has put out a score of records since then. The duo picked up a backing band for 1995’s “John Henry,” gained further popular visibility with their themes for “Malcolm in The Middle” and “The Daily Show” and earned a Grammy for their children’s album, “Here Come The 123s.” With a shift to the band format, Flansburgh says their sound got a little safer, but live shows got really fun.

“We did a show in Boston where we did all of our songs A-M, then we did N-Z, on two different nights,” Flansburgh recalls. ”Just completely random, but we’ve been writing songs for 30 years, so we can do a set of songs that are A-M and it feels like a valid set.”

A 30th anniversary tour for “Flood,” interrupted by Covid last year and now moved to 2022, dovetails with the launch of “BOOK” and gives fans a chance to take in the full scope of their work. They’ve been playing songs from “Mink Car,” for example, their semi-obscure eighth album that was released on and quickly eclipsed by the events of 9/11, then taken out of circulation entirely when the label, Restless Records, went out of business.

“Doing ‘Mink Car’ is kind of for us,” Flansburgh says. “It was a record we spent a lot of time on and collaborated with the dearly departed Adam Schlesinger [of Fountains of Wayne]. I think it didn’t really get a public hearing because of events beyond anyone’s control. It’s something we’re proud of.”

But as much as the tour might look like a victory lap, the Johns are still more interested in pushing their music forward. Case in point: a mysterious song showed up in the setlist early in the tour last year. A fan video of the performance played backwards revealed the band had learned to play and sing “Sapphire Bullets of Pure Love,” a deep cut from “Flood,” entirely in reverse. Google “Stilloob,” (“Bullets,” inverted phonetically) and prepare for some major David Lynch vibes.

When I asked if there was some deeper reasoning behind this remix, whether the song had taken on some new significance with age, the tension between entertaining and experimenting peeked through.

“It had nothing to do with the original song,” Linnell says. “We were just trying to come up with something interesting. It’s kind of fun to piece together in the laboratory how to perform a song live with a band. It’s one of my favorite experiences.”

Particle men

Laboratory is a good word.

The Johns are as much scientists as artists, and, whether live or in the studio, their music is a testing ground for theories about composition and experiments with obscure particles of the musical universe. While they haven’t abandoned the raw, crowd-pleasing energy of live shows, they’ve worked to recapture the eccentric feel of drum machines and synthesizer samples on their recent studio recordings. From 2011’s “Join Us” on, the band has taken a sharp turn away from music that sounds kind of like kid stuff into territory increasingly more singular and experimental.

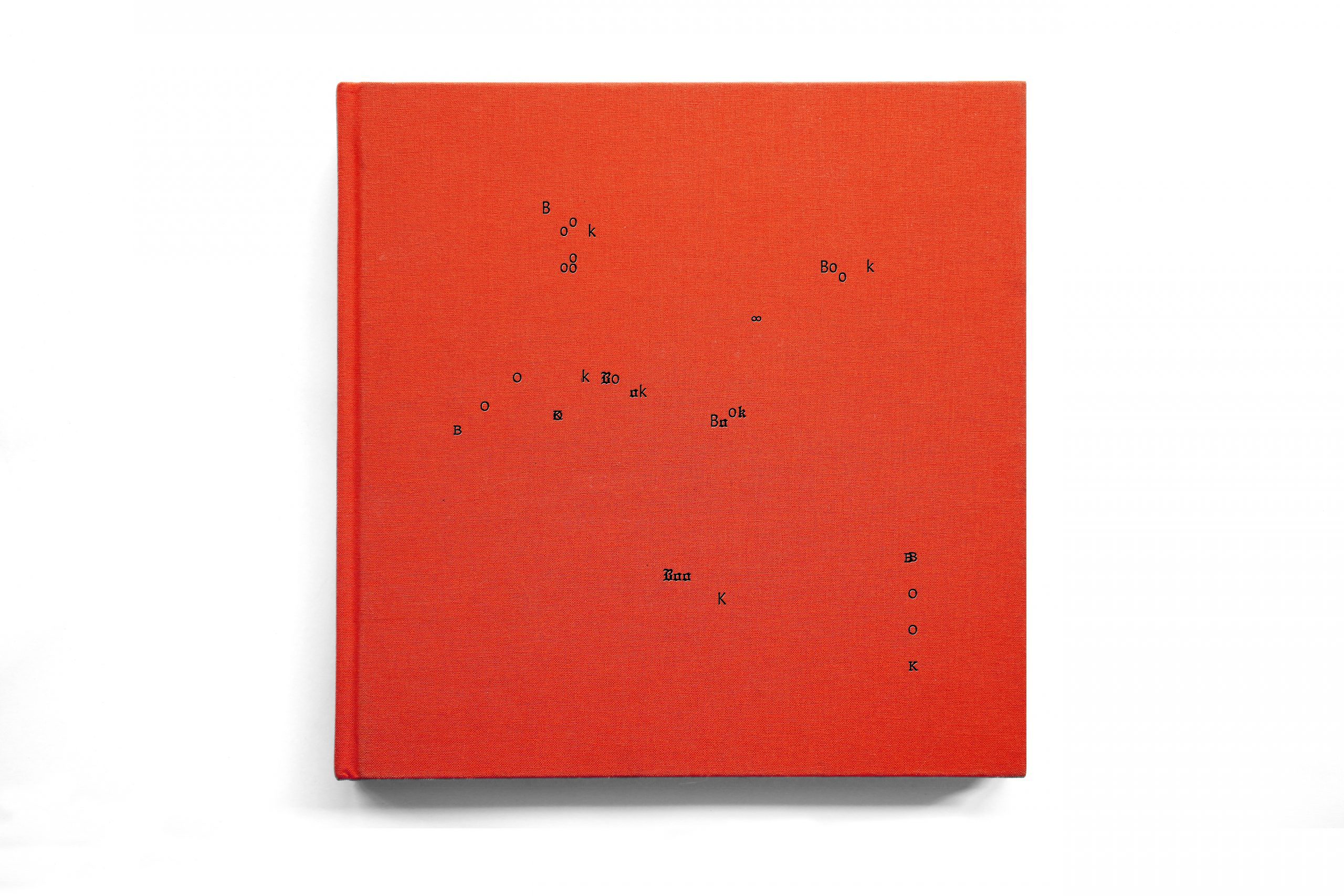

With “BOOK,” they wanted to immerse the listener completely in They Might Be Giants’ world. In addition to a CD, vinyl, cassette and digital release (don’t bother trying to snag the very limited edition 8-track; it’s long sold out), They Might Be Giants have paired the album “BOOK” with … yeah, a book.

“On my personal bucket list was making a book that was beautiful and cohesive and different from the kinds of books I’ve seen before,” Flansburgh says. “It wasn’t our goal to just make something fancy, but to make something fancy that’s elevated, an interesting object to have.” It was important to both Flansburgh and Linnell to craft an experience as much as simply release a record. Flansburgh cites as a lofty inspiration George Harrison’s sprawling post-Beatles masterpiece “All Things Must Pass.”

“With the book, you can control a little more,” Linnell says. “You’re issuing an object with a set sequence of songs; it was meant to be listened to in this way. Online, people kind of download willy-nilly; this was a return to that idea of curating something.”

The Johns worked with Brooklyn photographer Brian Karlsson and New York graphic designer Paul Sahre to craft something more than your typical coffee table book of art photography.

Sahre is a longtime collaborator with the band, creating the visual language for the last 10 years’ worth of their albums, events and music videos. Flansburgh describes him as “the Jay-Z of graphic design;” Sahre has been a fan since he discovered Dial-A-Song as a student in design school. The mutual admiration makes for an easy, organic partnership that helps realize whatever over-the-top ideas the Johns can come up with. In this case, they had been discussing doing a book for some time, and they decided to go “ridiculously analog,” as Sahre puts it.

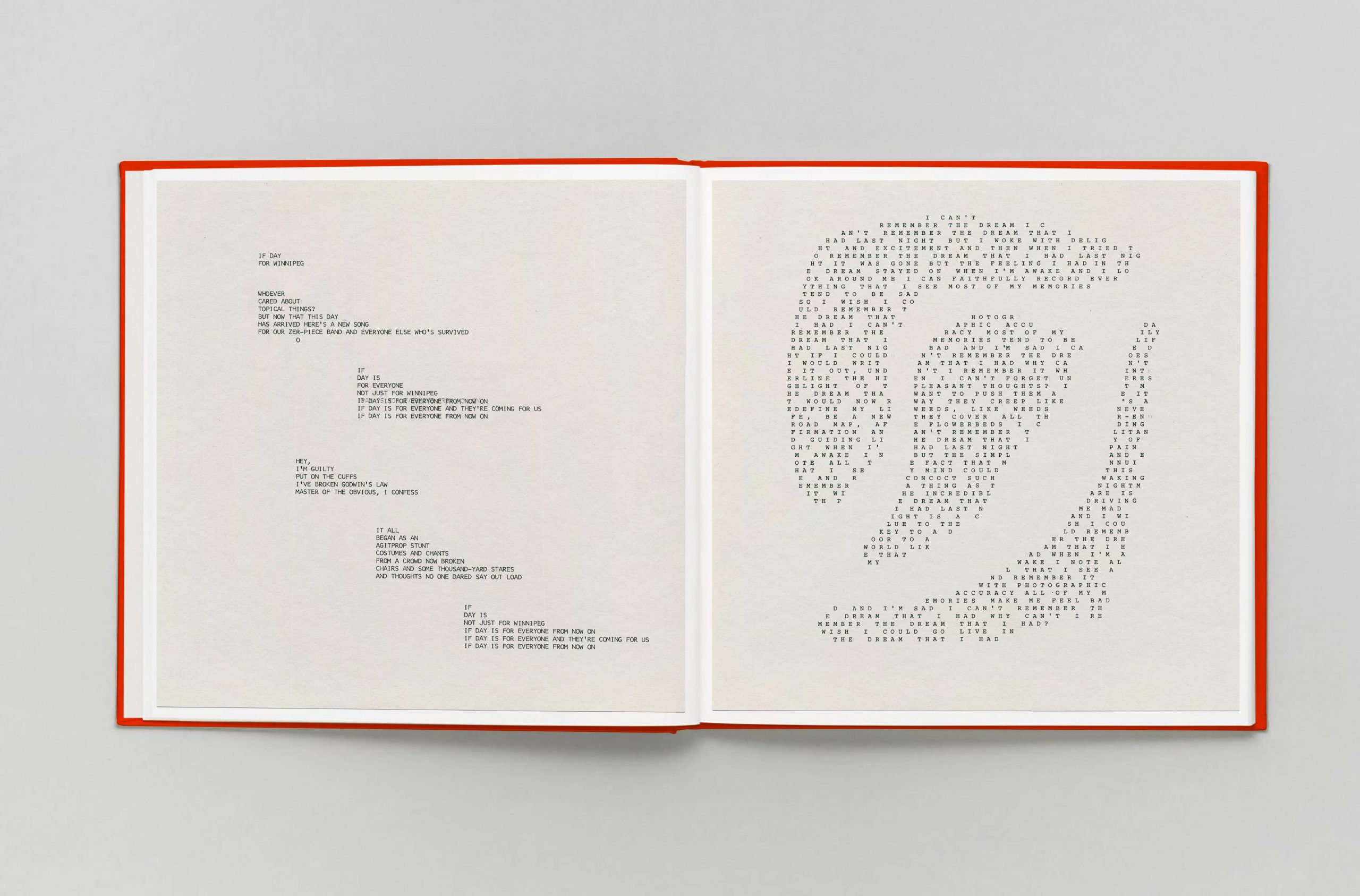

For the book, Sahre manually typed out each of the album’s songs on an IBM Selectric III typewriter, creating abstract images from the words. Some lyrics are laid out fairly straightforward; others rotate around the page, stack in layers and coalesce in dense, playful, sculptural forms.

“There’s one place where the type runs over itself and spins in this trippy way,” Sahre says. “I typed it out straight, then took the sheet out of the typewriter and put it back in at a slightly different angle, lined up one letter, then typed out the exact same thing up and down. Over and over.”

A spread from ‘BOOK,” courtesy TMBG

If it sounds crazy, or at least tedious, nothing good comes without work.

“Any time you’re doing something like this, the engagement is nine-tenths of it. I’ll get these cryptic emails from [Flansburgh], ‘you are genius’ typed backwards, and that’s the approval. It’s a privilege to work with them,” Sahre says. Still, he adds, “If there are any graphic designers out there planning something like this, do not do it, email me first.”

Illustrating the songs on “BOOK” with Karlsson’s candid, intimate street photography was a natural fit. He was recruited to the project by Sahre, and Flansburgh immediately connected with what he called Karlsson’s “egoless, outward-looking style.” For his part, Karlsson finds They Might Be Giants’ songs to be a perfect match for his approach to making photographs.

“A lot of time you’re responding to impulse, whether it’s music or photography, and only after, when you’re nailing things down and shifting things around until they fit just the right way, does it become something special,” he says.

His images can be as oblique as They Might Be Giants’ lyrics: a piano half-sunk in sand; an overturned box spilling plastic forks across a sidewalk; a man passing by the camera and his serpentine shadow seemingly seeking escape from his body. And like their songs, they can leave an itch you want to scratch. “I’ve always found in all forms of art that things that aren’t necessarily completely spelled out are the most interesting, the most evocative,” says Karlsson. “If you don’t give all the information to the viewer, there can be all these different realities.”

Wait actually yeah no

There’s a favorite parlor game among hardcore They Might Be Giants fans, trying to suss out hidden meaning from the band’s enigmatic references and tangles of polysyllabic lyrics. A fan-created wiki page, “This Might Be A Wiki,” catalogs the breadth of their work, offering sometimes dozens of interpretations for every song. Chasing “Particle Man” down that rabbit hole, though, can be a distraction.

“We’re not trying to be unknowable, the masters of mystery,” Flansburgh laughs. “Even a song like ‘Particle Man,’ it’s a story about the characters in the song, it’s almost like a children’s rhyme. You’d think the song is like ‘Animal Farm’: ‘Triangle Man is clearly Brezhnev,’ and you’re like, ‘What?’”

OK. But on “BOOK,” like many of their albums, there’s that tantalizing sense of some undercurrent, a wink and nod just below the surface.

Flansburgh concedes on making an album, “when we pull all the songs together, we sometimes realize the shape of the world we’re living in.” He compares “BOOK” to their 2007 album, “The Else.” “[It] was made at the height of the Bush administration, and it’s a very acid record, it’s kind of gloomy in a way. Looking at this record, I see a little of the worry of the Trump administration maybe infected us inadvertently.”

A person could be forgiven for reading political commentary, or at least a sense of profound discontent with the state of the world, into the lyrics of “BOOK.” One song observes the unrelenting outrage of “tiny voices trapped in a hothouse without windows, devoid of air / index fingers raised in objection making circles that lead nowhere.” On another, “Drown the Clown,” Linnell sings over the sound of a discordant calliope, “can’t resist this rabbit hole / can’t deny this troll,” almost daring usto guess which clown he’s talking about. He hesitates to indulge the suspicion, though: “I think if you can pull off a song that expresses a political view, that seems kind of lucky.” But he cautions, “We’re not here to just vent our frustrations. A song with a blunt political view is often kind of a vibe killer.”

Flansburgh and Linnell each pointed to “If Day for Winnipeg” as one of the album’s more satisfying successes. Lyrically, the song is about a grim historical footnote: Canadian government officials attempting to encourage the purchase of war bonds in 1939 apparently staged a mock takeover of the city of Winnipeg; think “War of the Worlds” meets “The Man in the High Castle.” The subject matter is specific, weird and surprising, but it was an afterthought to the music itself.

“The melody suggests the lyric,” Linnell says, “rather than the other way around.”

The song “If Day” began as a snippet of oddly tuned microtonal bell sounds Linnell was tinkering with. He sent them to Flansburgh, who recombined it with a drum loop and distorted tuba sounds to create a broken-mirror jingle simultaneously cheery and cringey. Flansburgh added the haunting lyric last, almost as if it had written itself for the song. The track is typical of their improvisational, back-and-forth songwriting.

“For me it’s interesting to participate in the process. If I’m not the acrobat, I get to be the trampoline builder,” says Flansburgh.

On another track, “wait actually yeah no,” Linnell sings about a maddening process of sifting through false starts to find a coherent thought: “pair of white magician gloves, camels in a caravan / wait um yeah no / thing you haven’t tried before, misremembered anecdote / yes but not that.” I tell Linnell I can relate to that sense of mounting desperation and wonder aloud if it was a little peek into their process. “No, I didn’t really think, ‘oh, this one is about songwriting,’” he demurs, I’m sure with an impish grin. “I like the sense that a song exists in an uninterpreted form.”

Before I can press further, the guys behind “Synopsis for Latecomers” remind me, “That’s all the questions that time will permit.”

‘BOOK’ cover, courtesy TMBG

This article first appeared in the Fall 2021 issue of Brooklyn Magazine. Click here to subscribe today.

You might also like