'Black Power Conference' by Vincent Smith, 1968 (Courtesy Alexandre Gallery)

A passionate painter and oracle of Black culture gets his due

In 'For My People,' a Vincent Smith retrospective, an influential and challenging voice rings out from the civil rights and Vietnam era

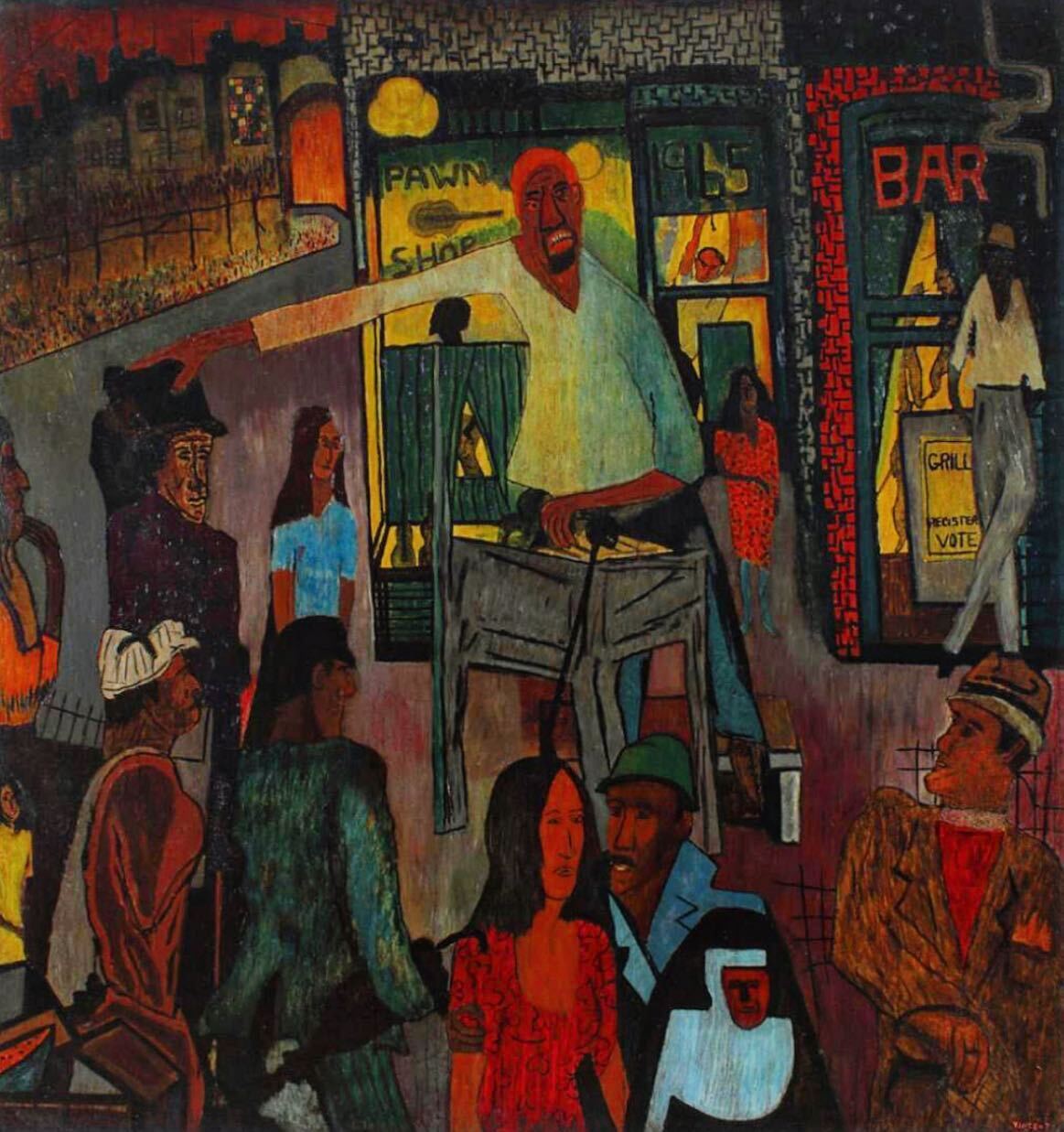

In “For My People,” a 1965 painting by Brooklyn-born artist Vincent Smith, a street preacher stands on a corner, his right arm outstretched as a crowd circles, half-engaged. Behind him is a pawn shop, next to a bar—“the twin symbols of spiritual poverty in Black America,” in Smith’s own words. A white face can be seen peering from the pawn shop window, nervously observing the word being delivered.

But who is the orator? With a shock of red hair, the evocation of Malcolm X is unmistakable. Less obvious is that the central figure is also an allusion to Ras the Exhorter, the “nowhere man-thief” of Ralph Ellison’s “Invisible Man.” And even less obvious still is that Ras the Exhorter was inspired by the real-life Ethiopian king Ras Makon, who defeated the Italians in 1885. In Smith’s world, art imitates art imitates life.

Today, “For My People” beckons to Lower East Side passersby through the vast front window of Alexandre Gallery’s new location at 219 Grand Street, where “For My People “ is also the name of a Vincent Smith retrospective on view through next month. The brooding composition by Smith provides a brilliant and jarring snapshot of just one moment from a dynamic career of one of the most experimental, influential, and underexposed painters of the Black Arts Movement. Comprising 16 of Smith’s works, spanning from 1954 to 1972, the exhibit charts the artist’s gradual evolution from cubism to collage.

‘For My People’ by Vincent Smith, 1965 (Courtesy Alexandre Gallery)

Smith was born in 1929 in Bed-Stuy, but his parents—both immigrants from Barbados—moved to Brownsville shortly after. He was raised in the African Orthodox Church and showed an early interest in art, starting piano lessons at age 9. As a teenager, Smith stalked Harlem’s jazz clubs, where he counted legends like Charlie Parker as close friends.

“For My People” kicks off with three artworks from the 1950s, Smith’s first years as a painter. The story goes that in 1951, a 22-year-old Smith was back in Brooklyn working at the Post Office after spending time outside the city—first working on the Lackawanna Railroad, then serving in the Army down south. “My nine months spent in the south was a realization and a revelation,” Smith recounts in Dr. David Driskell’s 1988 essay “Vincent Smith: An Overview.” “When the convoys moved out I saw the other side, the big white mansions, Greek columns, magnolia trees, lush vegetation.”

Smith decided to become a painter after seeing a Cezanne show at the Museum of Modern Art with artist and friend Tom Boutis. “I came away with the feeling that I had been in touch with something sacred,” Smith is quoted in Sharon F. Patton’s 1989 essay, “Riding on a Blue Note.” By 1953, Smith had received a scholarship from the Brooklyn Museum Art School and taken a basement studio next to his parents’ home, synthesizing his fascinations with Mexican painters, German expressionism, and African art into smoky cubist genre paintings like “Pool Room,” “Street Scene,” and “Saturday Night in Harlem”—all of which appear in this retrospective.

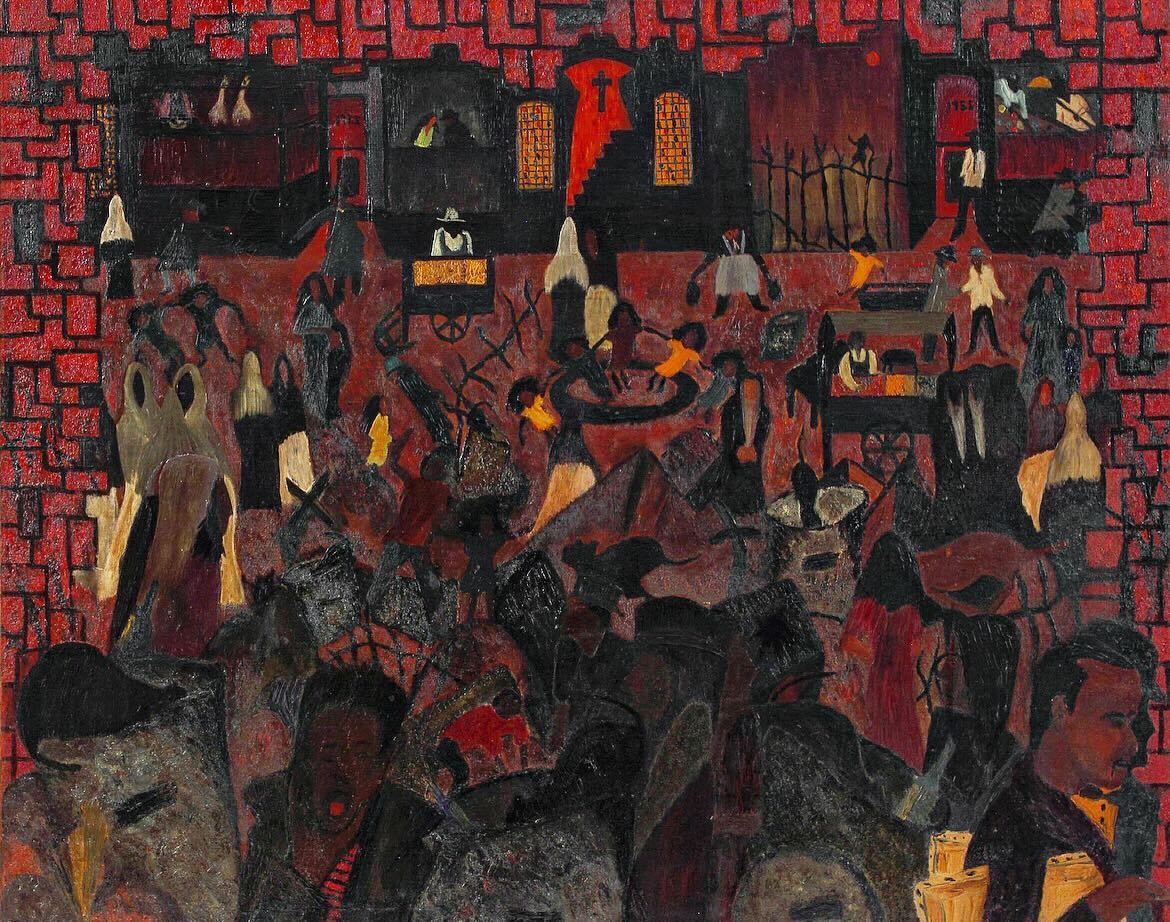

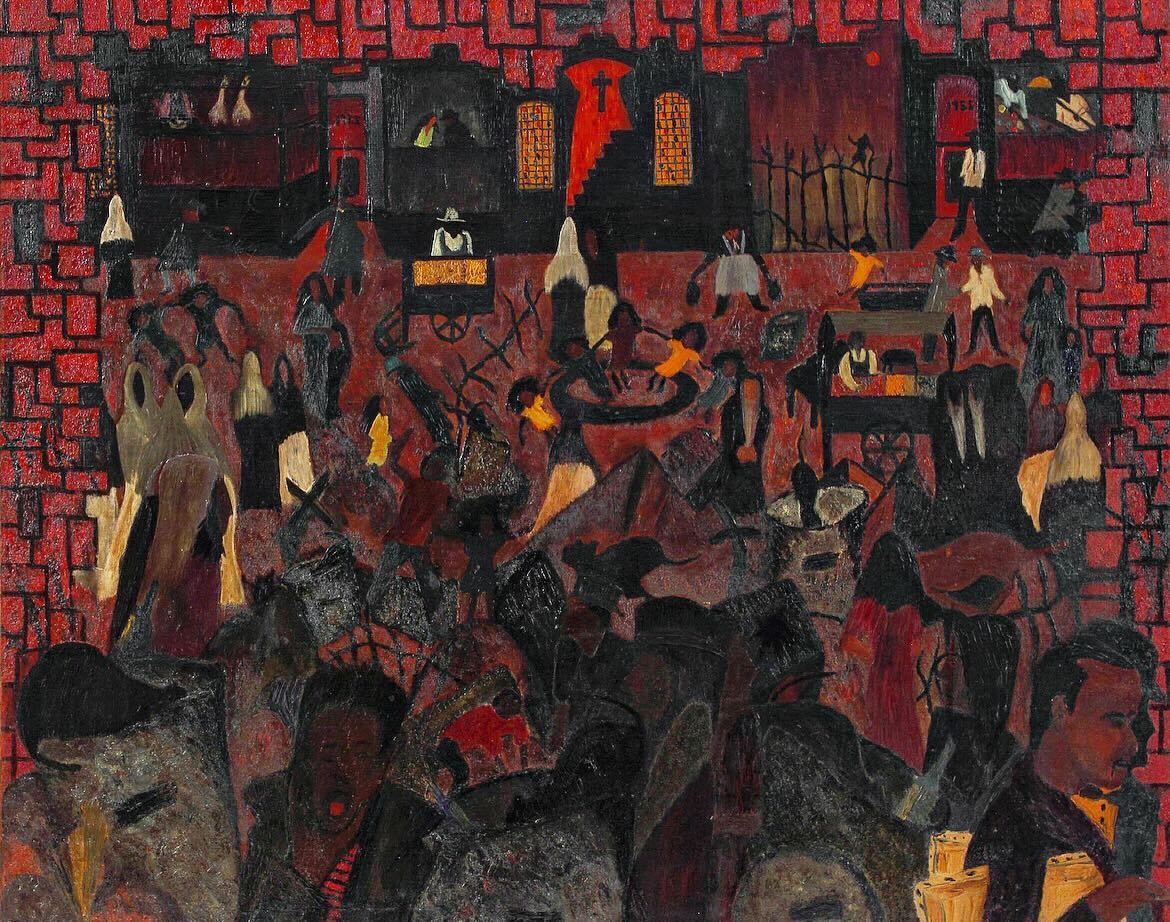

‘Saturday Night in Harlem’ by Vincent Smith (Courtesy Alexandre Gallery)

People prove the central focus of all Smith’s paintings, and also his career off the canvas: He participated heavily in the city’s avant-garde scene, building community with a diverse roster of Black creatives like Ted Joans, Sam Middleton, Virginia Cox, and Richard Mayhew.

“We were a strange group because people didn’t know what to make of us,” Patton quotes him in her 1989 essay. “They were used to black musicians and performers, but the visual arts were sacred territory. Most people I came in contact with never knew a Black painter nor had they hardly ever heard of one.”

‘Street Scene’ by Vincent Smith (Courtesy Alexandre Gallery)

By the 1960s, Smith began mixing sand with his paint and adding collaged elements like news clippings. If Smith’s artworks from the 1950s are appetizers in this exhibition, then these textured canvases make the main course. Works like “Martin Luther King” from 1969 and “Black Power Conference” (1968, top of page) pull from Smith’s involvement in the civil rights movement, evoking a vast spectrum of emotions while crafting a valuable historical record. The former is a eulogy pairing a found photo of King’s funeral procession alongside a cracked handprint, and the latter an abstract echo of “The Last Supper” filled with modern personalities and a dash of mirth.

‘Martin Luther King’ by Vincent Smith, 1967 (Courtesy Alexandre Gallery)

The same year man landed on the moon, Smith secured an exhibition at the prestigious Studio Museum in Harlem and moved into a three-story studio that allowed him to work on a larger scale, exemplified by his works from the early 1970s. At the same time, Smith was considering the role of storytelling in his work. Windows became his narrative vehicle of choice, standing out against rich brick red walls well-suited to his continued use of oil and sediment.

“Smith didn’t shy away from showing the quiet suffering that can result from urban poverty,” Alexandre Gallery archivist Emma Crumbley explains. Darker pieces like “Ritual Man” (1972) and “Home From Vietnam” (1972) voyeuristically depict melancholy figures seen through solitary window panes. However, Crumbley adds, “I think it’s important to note there was a lot of celebration in his work, too.”

‘Ritual Man’ by Vincent Smith, 1972 (Courtesy Alexandre Gallery)

Brighter artworks like “Soul on Top of A Peach Tree” (1972) play with themes of community care and the radical joy that springs from social revolution and isolation at play on Smith’s canvases.

‘Soul on Top of a Peach Tree’ by Vincent Smith, 1972 (Courtesy Alexandre Gallery)

The artist traveled extensively throughout the 1980s until his death in 2003, long after “For My People” leaves off. Smith spent the rest of his life exhibiting art and earning accolades, but also facilitating connections between his peers by mentoring younger artists and hosting a program called “Vincent Smith Dialogues with Contemporary Artists” on WBAI-FM Radio. Brooklyn spirit shines across the artist’s entire career. “He carried throughout his life this connection to the community that he came from,” Crumbley says.

Still, Smith remains vastly underexposed to the general public. Maybe because Smith’s style is less immediately accessible than that of confidantes like Romare Bearden and Walter Williams, or maybe because you can’t frame social impact on a wall like you can a painting. Crumbley hopes this exhibition will spur further awareness of Smith’s work, and in turn, more scholarship. Mysteries remain.

As she stands before the painting “For My People,” Crumbley wonders what kind of pulpit the central character’s standing at. The best she can do is hazard a guess.

You can try the same yourself: The retrospective will be on view at Alexandre Gallery through Feb. 26.

You might also like