'Sirens,' 2019-2021 (Courtesy Nan Goldin and Marian Goodman Gallery)

The ‘Siren’ Song of Nan Goldin

The trailblazing photographer is still exploring new ground: Next month she makes her filmmaking debut at the Venice Biennale

Nan Goldin, one of the most influential photographers of her generation, never actually set out to be a photographer. “I always wanted to be a filmmaker,” she says. This, from the the artist who in 1979 rocked the photo world with “The Ballad of Sexual Dependency,” her legendary 45-minute operatic show of 800 color slides.

Now, four decades after the debut of “Ballad,” she will finally realize her filmmaking dream: This April, Goldin will make her digital debut at the Venice Biennale with her film, “Sirens,” her first foray into video. And in October, the Moderna Museum in Stockholm will present the first comprehensive retrospective of Goldin as a filmmaker, focusing exclusively on slideshows and video installations.

A lot of time and space have passed since “Ballad” was first shown at New York’s Mudd Club at the dawn of the 1980s. In 1985, it became a full-fledged museum piece, finding its way into the Whitney Biennale. The following year, 127 of the photos were published as a book, and from there the rest is history. “She was making photographs of her life,” says Marvin Heiferman, curator and writer who has known and worked with Goldin since the late 1970s. “She has always photographed worlds from the inside.”

Cookie Mueller at Tin Pan Alley, 1983 (Courtesy Nan Goldin and Marian Goodman Gallery)

Highly confessional and deeply gritty, “Ballad” helped canonize the No Wave aesthetic. “I’m not modest about it,” she says today. “I created a sea change.”

To this day “Ballad” remains a standard of the confessional style of photography. “I would go as far as to say her work has come to represent an entire style,” says British curator and writer Susan Bright.

And in another sea change of sorts, Goldin is now taking her eye to film. Only instead of documenting worlds from within, she’ll be commenting from the outside: While “Ballad,” with its hundreds of snapshot-like portraits sequenced against a choppy pop music soundtrack, can be seen as its own form of moviemaking, “Sirens” says Goldin, “is my ode to movies.”

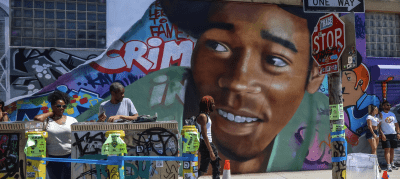

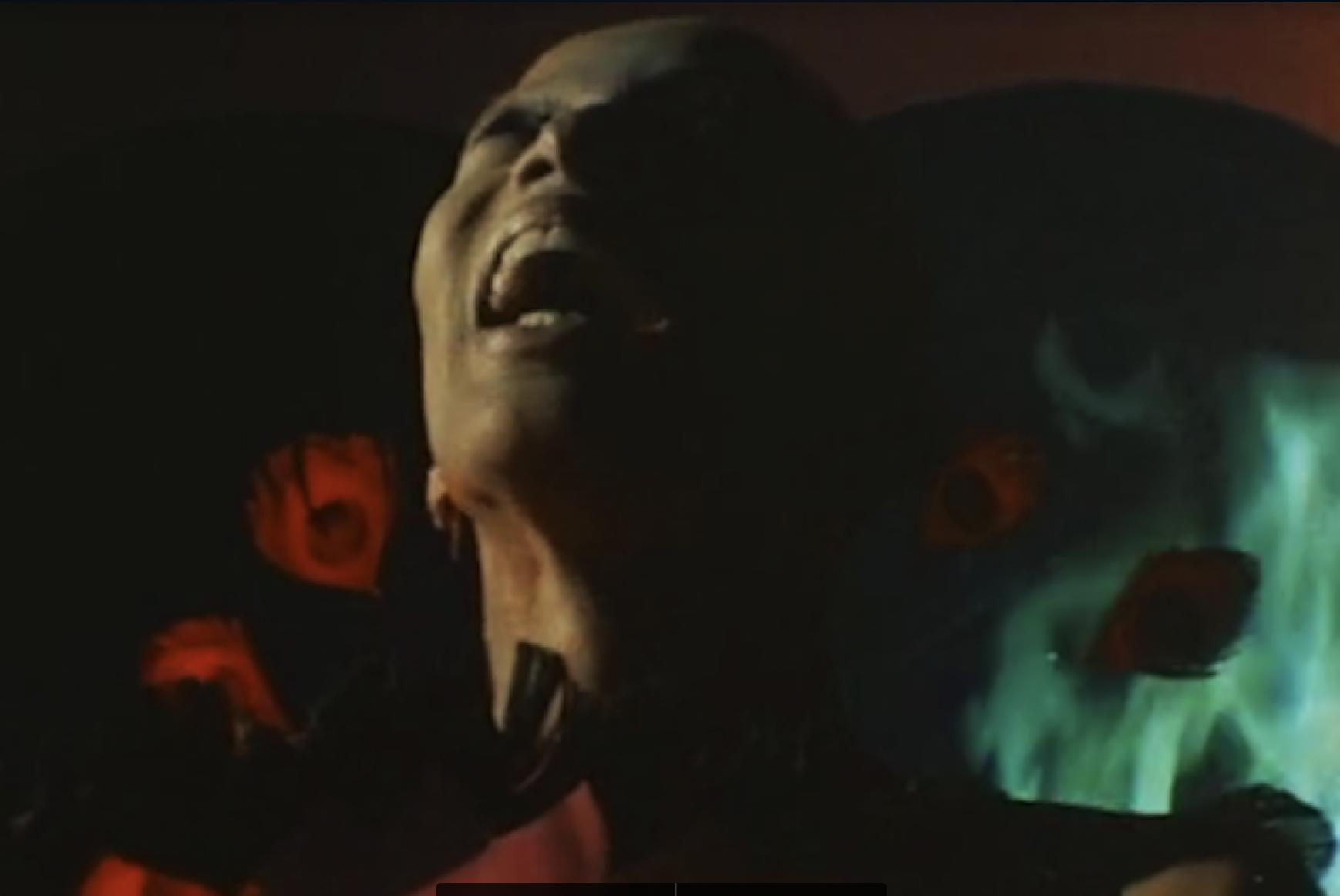

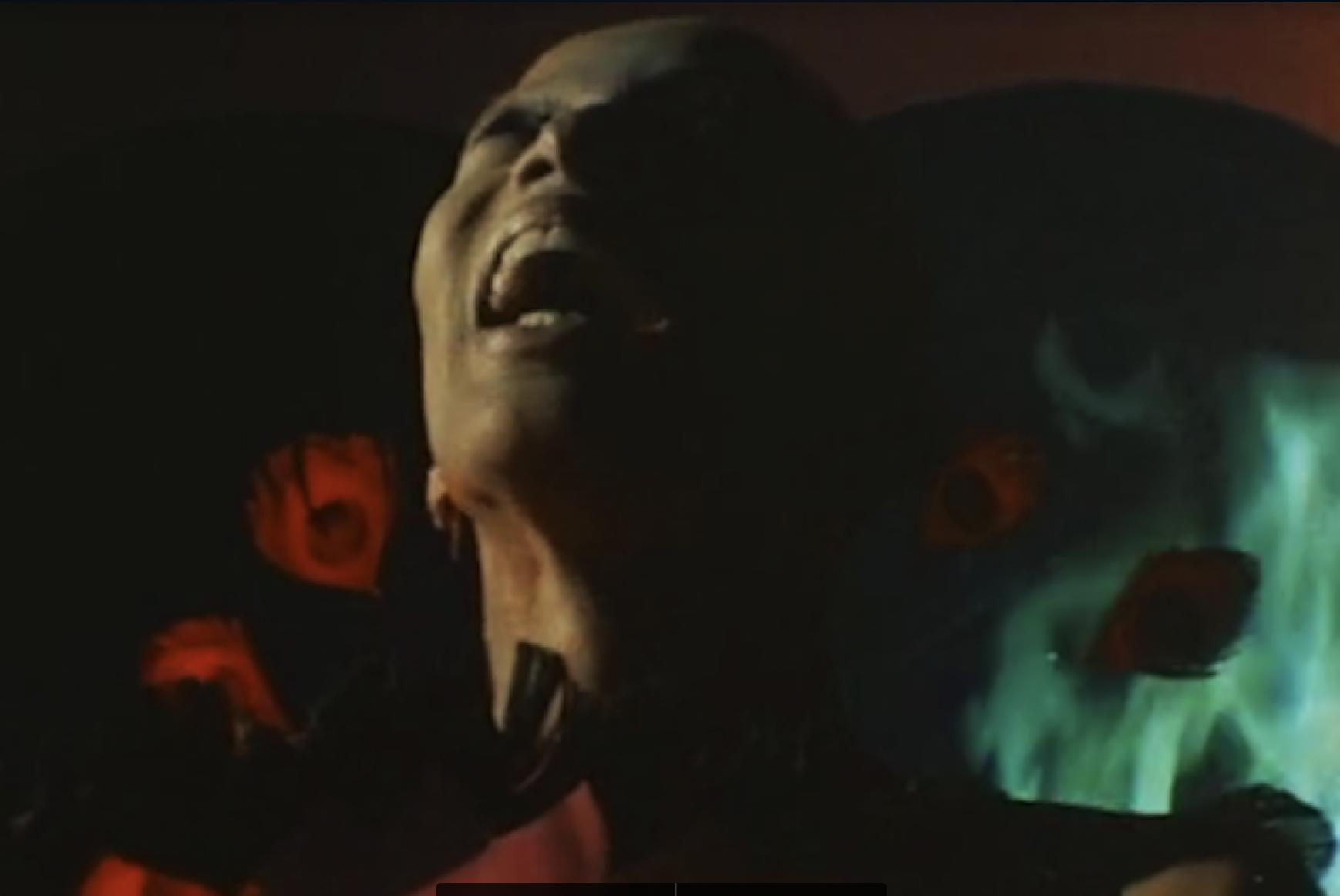

Set to a score by composers Mica Levi, Soundwalk Collective and Franz Schubert, “Sirens” is a 16-minute, impressionistic film that comments on the experience of addiction. It is made up of mash-up scenes from 30 of Goldin’s favorite films, including clips from Kenneth Anger, Michelangelo Antonioni, Henri-George Clouzot, Jack Smith, among others.

The work takes its name from the enchanting Sirens of Greek mythology, who lured sailors to their untimely deaths on rocky shores. Goldin’s “Sirens” entrances the viewer into the sensuality and ecstasy of being high. The work is dedicated to Donyale Luna, the world’s first Black supermodel, who died of a heroin overdose in 1979. After seeing Luna’s performance in the 1972 Italian film, “Salome,” Goldin says, “I could tell Donyale was really high, so I decided to make something about that euphoria.”

‘Sirens,’ 2019-2021 (Courtesy Nan Goldin and Marian Goodman Gallery)

‘When are you going to kill yourself?’

Goldin, 68, was born in 1953 in Washington, D.C., and now lives in Clinton Hill. Raised in an ambitious, middle-class, Jewish family, she was just 11 when her 18-year-old sister, Barbara, whom she worshipped, committed suicide by lying down in the path of an oncoming train. Goldin has often said she was very close with her sister and darkly aware aware of some of the forces that led her to choose suicide. “What killed her was that she was born at the wrong time,” she says.

Almost as traumatic as the loss of her sister was what happened next. In 1965, teenage suicide was a taboo subject and people didn’t talk about issues of mental health. The reaction from family and friends, as Goldin recalls it, was shocking: “Kids threw stones at me and shouted, ‘When are you going to kill yourself, like your sister did?'” She says her sister’s psychiatrist told her that she, too, would kill herself. Instead of dying, she began to take photos.

At 14 Goldin left home, moved into a group flat in Boston, and began smoking weed and dating older men. She eventually enrolled in the School of the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, where she studied photography.

In 1978, still reeling from the loss of her sister, she moved to New York where, seeking a substitute family, she became part of a group of restless, transgressive young men and women involved with sex, drugs, and violence in an almost lawless post-Stonewall subculture. She lived with them, understood them, photographed them.

It was also here that she became addicted to heroin.

“I wanted to get high from a really early age,” Goldin said in a 2014 interview with The Guardian. “I wanted to be a junkie. That’s what intrigues me. Part was the Velvet Underground and the Beats and all that stuff. But, really, I wanted to be as different from my mother as I could and define myself as far as possible from the suburban life I was brought up in. Drugs set me free, and then they became my prison.”

Goldin went into rehab in 1988—just three years after “Ballad” made her a star—and emerged raw: “I came out of rehab and I didn’t even know how to catch a bus,” she says today. “I honestly didn’t know who I was or what I was when I first got clean. When I say the camera has kept me alive, I mean it literally. My work is who I am. For such a long time I was fueled by rage. Only the junk stopped that anger, but it came back … big time!”

And so did the junk. Only this time, in the form of OxyContin

Pursuing Purdue

In 2014 Goldin was prescribed the pain-killing narcotic for the tendonitis she was suffering from in her left wrist. In spite of taking the pills exactly as the doctor prescribed, she quickly became hooked. “The first time I got a ‘script it was 40 milligrams and it was too strong for me; they made me nauseated and dulled. By the end, I was on 450 milligrams a day. Eventually I was crushing and snorting them.” When doctors refused to supply her any more, she turned to the black market, and to cheaper hard street drugs whenever she ran out of money.

Emerging from rehab again in 2018, she began reading up on OxyContin and its active ingredient oxycodone, a chemical cousin of heroin, and twice as powerful as morphine. What she learned was that OxyContin was manufactured by Purdue Pharma, a company owned by one of the world’s leading cultural and academic philanthropists—the Sacklers.

Purdue played a “special role” in the country’s opioid crisis, according to a New Yorker deep dive on the Sackler family, which notes the company “was the first to set out, in the 1990s, to persuade the American medical establishment that strong opioids should be much more widely prescribed—and that physicians’ longstanding fears about the addictive nature of such drugs were overblown.”

According to The U.S. Department of Justice in a 2020 hearing before the Committee of Oversight and Reform at the House of Representatives, Purdue Pharma and the Sackler family spent decades “misleading the DEA, defrauding the United States, paying kickbacks to companies that would steer patients on to OxyContin, and exacerbating the opioid epidemic. All the while, the Sackler family profited immensely from the deaths of millions of Americans.”

Making the link between her own addiction to OxyContin and the ongoing opioid crisis, Goldin founded Prescription Addiction Intervention Now, or PAIN, with the initial goal of highlighting the full extent of art institutions’ financial collusion with the Sackler family—and thus their complicity in a public health crisis that has led to hundreds of thousands of deaths nationwide since 1999.

“I picked this fight because I was an opioid addict myself,” she says.

Modeling PAIN on ACT UP, a group of grassroots activists that, in 1987, united in anger and committed dramatic acts of civil disobedience to address the AIDS crisis, media-savvy Goldin organized actions against art institutions with protests dramatic enough to capture public attention. The goal was to put an end to ‘toxic’ philanthropy.

On March 10, 2018 Goldin and a group of about 100 demonstrators marched into the Sackler Wing’s Temple of Dendur at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, scattering pill bottles into the moat with mock labels such as “Side Effect: Death,” and “Prescribed to you by the Sackler family.” “It was about a thousand bottles bobbing in the water,” as Goldin describes it.

Next came the ‘die-ins.’

Storming New York’s Guggenheim Museum, Goldin and her group lay down on their backs amidst a sea of fake opioid prescriptions, chanting slogans like: “Sacklers lie; people die! People, not profit!”

The activism was effective: A month after the ‘die-in’ the Guggenheim announced it would no longer accept Sackler contributions. And, in 2019 the Metropolitan Museum of Art went one step further, they removed the Sackler name from seven exhibition spaces, including the wing that houses the iconic Temple of Dendur.

Soon after, the Louvre in Paris removed the Sackler name, as did the Serpentine North Gallery (once called the Serpentine Sackler Gallery) in London.

At London’s National Portrait Gallery, Goldin threatened to boycott a potential retrospective if they accepted the $1.3 million dollar donation that the family had been offering. Of course, the gallery turned down the funds, marking another victory in PAIN’s fight over the ethics of art funding.

It seems natural to draw a straight line between Golden’s activism and her art. “I was actively involved with the AIDS crisis and my work was alway credited with being political on a personal level,” says Goldin. “Artists, in this day and age, can’t stay silent. They have to find a cause, they have to find their fight.”

They have to find their own Siren song to sing.

For further information on the Moderna Museum’s Goldin exhibition, go here. The Venice Biennale exhibition opens April 23 and runs through November 27, 2022. Tickets are available available here.

You might also like