The alchemist: Meet BRIC President Wes Jackson

Three months into his gig, Jackson discusses his mandate at the arts organization, his upbringing, how hip hop saved his life and more

Like what you’re hearing? Subscribe to us at iTunes, check us out on Spotify and hear us on Google, Amazon, Stitcher and TuneIn. This is our RSS feed. Tell a friend!

Ask most Brooklynites if they know much about the arts organization BRIC, they might be able to tell you that it’s the group behind the immensely popular Celebrate Brooklyn! concerts in Prospect Park, about to enter its 45th year in 2023.

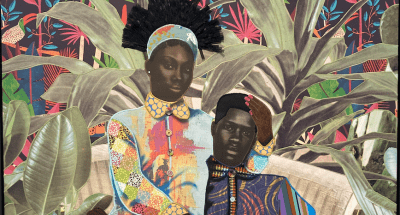

But BRIC Arts Media is of course much more than that. It is, as its name suggests, an arts and media institution anchored in Downtown Brooklyn, whose work spans contemporary visual and performing arts, media, and civic action. It’s a public media center, a contemporary art exhibition space, multiple performance spaces, a TV studio, artist work spaces and classroom.

And heading it all up is Wes Jackson, who took over as BRIC’s president in July from his predecessor Kristina Newman Scott. Jackson, who has had a career that is just as multifaceted as the organization he’s running, joins us on “Brooklyn Magazine: The Podcast” this week. He was the founder and executive director of the hugely influential Brooklyn Hip-Hop Festival from 2005 to 2020. He has run a business program designed for executives at Emmerson College. And he began his career producing concerts at his alma mater, the University of Virgina, for groups like the Nas, The Fugees, Dave Matthews Band the Roots and Tribe Called Quest before starting his promotions company, Seven Heads Entertainment.

We discussed his first three months on the job, his career, his upbringing and how hip hop — and lacrosse — saved his life. Jackson explains exactly why creative people are so important. “We are wizards,” he says. “We are alchemists.”

The following transcript of this podcast episode has been edited for clarity and flow. For the full conversation, listen wherever you get your podcasts.

You began this role on July 18, or at least it was announced on July 18. This will probably post on October 17. So that’s three months almost exactly. You’re probably still learning where the bathrooms are, but how’s it been?

It’s been great to put it succinctly. BRIC does a lot more than your typical arts institutions in terms of being interdisciplinary. I feel like a kid in the playground because you kind of get here and you go from the swings to the sprinklers to the jungle gym and you’re like, “I just want to stay here all day.” It’s … like a culmination of the weird career trajectory I’ve taken. It feels like a playground. What do you want to do today? What we are going to build today? So I love it.

Most Brooklynites associate BRIC with Celebrate Brooklyn. But you’ve got BRIC House, which is a public media center, you’ve got public TV, you’ve got contemporary art, like you mentioned, performance spaces, artist workspaces. So in all of this, what is your mandate?

You kind of hit it on the head. For years people didn’t understand that BRIC produced [Celerbate Brooklyn]. So we needed to solve that conundrum, which I think we’ve done pretty well. And then you’ll go to other people — particularly more cutting edge, cool visual artists — and they’ll be like, “Yeah, I know there’s a concert, but I’m not concerned with that. I want to be in your gallery.” You have these two constituents who don’t know about each other, but they love what we do. So I’m just trying to get them all together and then we can, as a unified voice, go out and say, “We got programming, we got educational programming in NYCHA. We’re in 30 public schools doing media and art education. We’re here as a resource for the community. And that beautiful concert that you go to is a part of it and we love that too.” And I want to continue to grow that brand.

This role is not actually your first time working with BRIC. You’ve worked with them over the years in what capacity?

At the Brooklyn Hip-Hop Festival, which was mainly in Brooklyn Bridge Park. To be honest, when I was struggling trying to figure out how to do this and find space, they were sort of giving me counsel about how to do this and how to navigate these waters, which I had no clue. So I was a bit of a student. And then through that BRIC TV, which is our curated channel, became a media partner for our festival. They were documenting our stuff and doing news pieces, helping us get the word out. And then I was brought in almost as talent because there used to be a show called B-Side, which would showcase new artists. So I was like a host there. It’s been sort of a windy road, but I love it.

Any hint as to what this year’s run of shows might or next year?

No. I’m not trying to be coy. They are busy brainstorming and having those foundational conversations with folks. But the big deal is it’s our 45th anniversary. Not many people last 45 years. So we got some tricks up our sleeve. We’re going to really come back and also invest in the infrastructure. We want to … do some more interactive installations, make that experience a little bit better, not better, but just enhance it. That’s what the team is wrestling with right now.

Let’s talk about your background a little bit. You mentioned the Brooklyn Hip-Hop Festival. Prior to that you were producing shows by people like Nas and the Roots and Fugees, Dave Matthews Band, Tribe. Where did this all start? You went to college at UVA, was that it, you were producing shows there?

I was also on the radio WTJU, that’s really where it started. I did a hip-hop show from 1 to 3, Sunday mornings.

I had a show in college radio from 1 to, it was 3 or 4. We got the worst callers. It was Friday night.

I used to do Saturday night. So people would go out to the parties, I’d leave early or not go. And then the after party was basically my show every night. I loved it. Sidebar, it’s kind of amazing how many really powerful people and successful people started on college radio. It’s such a great factory for when you don’t know what you’re doing, you’re like 18, 19 years old. So from doing the radio, I got involved with producing concerts at Virginia, which was quite great because I did Nas there, I did the Roots, I did the Fugees, I did Dave Matthews Band. And it’s all on the college’s dime. So I was able to make mistakes and build relationships. And then I come back home to New York afterwards and sort of started my life in the music business.

So then that’s when you started Seven Heads Entertainment. That was basically the gig before the hip hop festival. What is it? Management, production? A little bit of everything?

We started doing college radio promotions and my big client was Raucous Records. So, like, Talib Kweli, Mos Def, now Yasin, El-P and Company Flow, which is now Run the Jewels. I came in right with them to help get the word out to those sort of backpackers at college radio. And then I had Seven as a record label, which was basically my older brother Rob and one of my good friends from Virginia where the Unspoken Heard was a group. So then we were like, “Let’s just do this thing ourselves.” And then it was this sort of weird entertainment company that had his hand in three different pots. It was great.

I like that you used the word backpack because in hip hop circles, it was almost like a pejorative, but you’re a proud proponent of backpack.

Yeah, backpackers unite! It did fall out of favor, but now I have kids, like you do, and they listen to trap stuff and drill. I’m like, “Listen, everybody’s got to have their own thing.” I am A Tribe Called Quest, De la Soul, Black Star Artifacts. That stuff still bangs. It was a great era for it then. Yeah, yeah. It was a pejorative, but yeah, enough of that.

I saw another interview with you and you seemed to want to emphasize for the younger generation the history of hip hop. You were lamenting that no one knew really who Rakim was and his significance. There’s almost a disdain for learning about the history of the culture. I wonder what you make of that.

I very much am evangelical about hip hop culture. Hip hop saved my life when I was a little homesick kid from the Bronx away at boarding school. I listened to Rakim and De La Soul every single morning. I was like, “What would Rakim do? Rakim wouldn’t quit so I won’t quit.” I love hip hop. After my family it has been the most important thing in my life. So I like to go out there and tell a holistic story from politics and Black nationalism and anti-racism and feminism and this is what we were born in. But I do get sometimes … this lone cowboy vibe in hip hop that if you give respects to someone else, it somehow lessens you.

There were also people, Brian, maybe our age, who are doing a little, “Get off my lawn, it was better in my days.” But now having kids, it’s like you got to let everyone have a chance to breathe. Once elders like us go to the kids being like, “Your music is valid. Period. New thought: here’s my music,” I feel the conversations open up very, very quickly and we’re in a much better space.

You were a professor at Emerson. Education is a big component of what you’re into and what BRIC does. What areas do you lean into in your professorial career?

When I was doing the festival, maybe a couple years into it, I began to realize I don’t really like the music business part of it. Chasing agents and dealing with prima donnas and all this sort of stuff. So we started doing this educational thing. We used to call the Hip Hop Institute and I quickly began to realize, “Ooh, this is what gets me excited now.” Because I love seeing Nas in the performances, but this is a little bit more of a legacy. What we need to do, instead of teaching the artists how to do these business things, you need to teach a business person these skills that artists have. Collaboration, articulation, public speaking, problem solving.

I consider myself an artist. Am I a practitioner? No. Am I an artist? Yes. Because I love hip hop just as much as somebody writing rhymes. And I’m able to express that love through writing emails and writing proposals and building budgets, which is also an artistic venture. So we would really empower people to not get this elitist creative line, but bring your art to business.

A few years ago you did an interview with Sway Calloway, journalist, radio host, et cetera, et cetera. He called the Brooklyn Hip-Hop Festival, one of the most “credible” in hip hop. What did that mean to you?

Oh man, that meant everything. A shout out to Sway, who is a legend walking around us. He spread the gospel out there and he opened the door for almost every New York artist to say, “Now you good here, come talk about this.” You look at a Kendrick Lamar now, he built that infrastructure that allowed the L.A. scene to produce Kendrick because he was this ambassador. So when he said that, it was quite humbling. He is the model of this interdisciplinary excellence.

Now you can take that credibility and apply it to the gig at BRIC. What’s your take on the current state of Brooklyn culture right now?

It’s very simple. People are thirsty. They’ve been starved of this for a better part of two years. So to be honest, as much as I think our team is awesome and the actual content like the exhibition downstairs or what Diane [Eber, Celebrate Brooklyn’s executive producer] and them did in the park is super dope, people just want us to do something. People understood that arts and culture were a necessity right after food, clothing, and shelter because life is terrible with no art. I don’t think we had those conversations before. We were barred from going to see the art.

That’s the consumer side. On the creator side, you had people cooped up without an audience for two years and probably going crazy in their own way, but also they had nothing else to do but create, if they had the resources. So there’s an outpouring of new content hopefully.

I think you’re right. They’re like, “I’m going to tell you what, as soon as these restrictions up, you going to get these albums, you’re going to get the sculpture.” What was good is, being cooped up, you kind of were able to sort of consume more things. “Let me sit down and listen to this Khruangbin album because I’m not running around so much. Let me read this Michelle Alexander book.”

You were born in the Bronx. you went to private school. You went to private school in Manhattan and then boarding school [in New Jersey]. Culture shock?

Listen, you better make sure this don’t turn into a therapy session, you ask me that question. But it was, yeah, culture shock to say the least. Identity challenging, cruel also, but also empowering, enlightening, all sort of the sort of complex emotions. Challenging to say the least. We grew up in Soundview section of the Bronx. It was a good place. And we were kind of in this weird lower middle class working class enclave surrounded by NYCHA houses.

But me and my brother Rob, we were the typical smart kids who through that patriarchal, honestly, white savior thinking was like, “We’re going to save you and you. Not the rest of y’all though, the rest of y’all can go to public schools and if y’all get arrested and so be it.”

You were recruited essentially?

My brother Rob was. And then I just kind of followed his footsteps. But there was really this “Special Negro” thinking I’m going to fight: Back in the days in Antebellum times, if all Africans are subhuman, how do you explain Frederick Douglass, Booker T. Washington? And then there was this thinking like, “Oh, those are special Negroes. Every now and then a broken clock is right.” So there really is the sense of, we want the best and the brightest. I went to Buckley School in the Upper East SideT o give you a sense of who this Black kid from the South Bronx was going to school with: My brother went to school with a Rockefeller, with Nelson Rockefeller’s son, who had secret service in classes. I was in ninth grade and fourth grade with Donald Trump Jr.

Oh, no. You still in touch?

Yeah, yeah. We went out for lattes the other day. But you could imagine, what is that curriculum? What is that support system for me? If Don Junior is there, it is nothing. It was just like, “You should be happy to be here.” Which is tough to a young kid, but at the same time you were going to playdates at triplexes on Park Avenue and seeing people who, just, the world was their oyster. And then I would go home and see people kind of trapped in the system and I would be like, “Okay, so that doesn’t have to be a thing. This system that they’re putting us in is not the system. It’s the system they’ve given us. And I’m going to spend a lot of time to break out of it.”

What I’m proud of, what I’ve been committed to, what my wife is committed to, what all of our parents are committed to is now you got to bring that knowledge back to the community. That’s why I’m still here. I got that pull to come back because after that summer of reckoning, I said, I got to be closer to the people, my son’s friends from football team might get shot out on these streets. It’s real out here. So we got to stay in the community and give all of this knowledge and this experience that we’ve had from all of our experiences and we got to help break that cycle of poverty. Another important thing about me is my love of the sport of lacrosse

Really?

After hip hop, that’s my thing. That’s my bag.

Do you still play?

I coach. Me and five other folks. We founded about 15 years ago, the Brooklyn Crescents Lacrosse Club. Which was designed to grow the game and add some diverse voices to the game. I absolutely love it. That is my dream job, run around those kids coaching. As much as I love BRIC, in 20 years I hope I’m walking around with a pot belly blowing whistles because it is the most rewarding thing that I’ve done outside of my career.

But there was also, you’re going to prep school, playing lacrosse. There are wicked, wicked people there who said and did things that still bother me today. Even as I’m thinking about it now, I almost get pissed. I realized it wasn’t until I was a senior in high school that I finally had a syllabus that had a Black person on it. It took me till 12th grade and it was my civil rights class. And it was also that senior year before I had a teacher say, “Hey Wes. You’re a good writer.” Bill Treadway, Rest in peace, Mr. Treadway, Treads.

I did hear you in another interview talk about the idea of alchemy in your career in life.

Ooh. You really did your research. I love it. It’s like a Combat Jack level interview. I love it.

Can you elaborate on the idea of alchemy?

Hip hop, as a student of hip hop, is alchemy. Alchemy is turning nothing into something. So we had funding taken away from us for arts programs. So we created graffiti. We had no creative writing classes, so we became MCs. We had no technical engineering classes, so we became DJs. Most people quit. I didn’t quit, my brother didn’t quit, my father and my family hasn’t quit. Hip hop never quit. So when you have the ability to see through the challenges while you’re on your personal journey, you do get imbued in a very cinematic sense with this magical ability to turn lead into gold. But it’s really something out of nothing. I really encourage people to look at what we do and say, I think we are wizards. We are alchemists.

Check out this episode of “Brooklyn Magazine: The Podcast” for more. Subscribe and listen wherever you get your podcasts.

You might also like