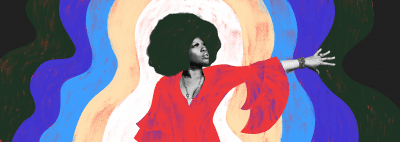

From left: Dana and Alden McWayne (Photo by Robb Klassen)

Dana and Alden are bringing jazz to Gen-Z

With serious musical chops and a sense of humor, the McWayne brothers are striking a chord on TikTok and in the clubs

It’s tempting to categorize Dana and Alden McWayne’s records, “Quiet Music for Young People” and the recent follow-up “Coyote, You’re My Star,” as introductory gems for first-time jazz listeners. The Oregon-bred brothers’ original music is approachable. It’s heartfelt, groovy, and most of the time, straight-up fun, especially their more vocal-forward tracks, like the viral grocery-store jam, “Let’s Go to Trader Joe’s,” and fun-loving bop “Ice Cream Song,” both of which feature the hazed-out perfect pitch of singer-songwriter Cinya Khan.

But the Dana and Alden project, which includes Salim Charvet on keys and sax, Eli Torgersen on guitar, and Andrew Mitchell on bass, contains multitudes. The band builds on a deep knowledge of jazz history and formal training, plus years of consistent gigging, to invert expectations by embracing improvisation in the hopes of capturing something that’s emotional, communal, imperfect, political and timeless.

The group’s new album, named after and inspired by a wild coyote that started howling outside the studio on their first day of recording, features a diverse array of styles — hip-hop, funk, reggae — that elegantly coalesce into an overall acid-jazz sound, surprising listeners at every turn. The instrumentals – soaring saxophone, heaving strings, dynamic drums and bass, transfixing synth — set the stage for sturdy thematic undertones, like family and nature (“Family Garden” features the transcendent voice of Brooklyn native Melanie Charles, as well as dialogue from the McWaynes’ mother), and anti-imperialism (“Popular Front” and “Paper Tiger” showcase the band’s devotion to the Palestinian liberation movement).

With the virality of myriad TikTok videos featuring the McWaynes — Dana on sax, Alden on drums — and friends covering favored hip-hop tunes (and Alden’s comedic @gucci_pineapple persona), the brothers, now based in Brooklyn, are using their burgeoning fame to expand their sound and give people their own take on “the jazz tradition” — something Dana and Alden believe younger listeners not only deserve, but also crave.

In contrast to the over-produced typical pop music output today, Alden McWayne says that “when you make something that’s more abstract, it’s quite refreshing to the ears.”

Dana and Alden McWayne sat down with Brooklyn Magazine to discuss their new record, the current state of jazz, how they’re using their platform to promote political change, and more.

This interview has been edited for concision and clarity.

I almost saw you guys open for Benny Sings last October at Webster Hall. How was that touring experience for you?

Dana: That was really the start of everything for us. We learned so much from watching Benny’s set every night, seeing how dialed-in they were. It was our first time ever truly touring. It was a fever dream sleeping on friends’ floors and couches around the U.S. to make it work. Our whole band packed into Eli’s Toyota Highlander. The fact that we made it through and still all loved each other after those 12-hour drives was a testament that we have something good going.

Fast forward to the start of this summer, opening for The Yussef Dayes Experience in Central Park.

Alden: That was a dream come true. They inspired us to really hit the shed and take our sound to a new level.

How’d you guys get connected with Dayes?

Alden: We kind of just became internet buddies and then he called me on WhatsApp and was like, “Open for me.” At first I was starstruck, but now it just feels like a blossoming friendship.

So do you guys remember your first legitimate jazz gig?

Dana: It all started in Oregon. Our dad took us to this Sunday jazz jam that he saw in the local newspaper, run by a guy named Kenny Reed, who was a bona fide local legend. He was from Crown Heights, but his car broke down in our hometown, Eugene, at some point and he just never left. But we started going to Kenny’s jam and we could barely play. He took us under his wing, mentored us, and before we knew it we were playing in his band Stone Cold Jazz around town two to three nights a week. Everything we do now is informed by how he brought us up in the jazz tradition.

What was the secret sauce that kept you coming back to play these gigs?

Dana: I was an anxious, insecure kid.

Alden: He was a little troublemaker

Dana: Yeah, going to Kenny’s jams made me feel like I belonged somewhere. I slowly figured out how to express myself through my instrument and deal with my emotions by playing music. I would have been an absolute trainwreck if I hadn’t had music and sax to hold me down.

Do you think your dad knew what he was getting you into?

Dana: Yeah, I think so. Music was really important in our family.

Alden: Our dad showed us Pharoah Sanders and John Coltrane — he put us on some crazy music as kids.

Dana: He would just take us to the public library downtown and let us loose. Alden and I slowly made our way through the entire CD collection. Whatever had a cover that we liked, we would listen. The music curator was a huge jazz head so it explains why we got turned onto what we did. We found Menahan Street Band in the library and never stopped listening to them. Now, driving through Brooklyn, on Menahan Street, is crazy for me.

You both now live in Brooklyn. Does the fact that your mentor is from here deepen your connection to the borough?

Dana: Yeah, and I didn’t really realize it until you say it now, but a lot of the music we grew up listening to is rooted here. We were obsessed with Daptone Records, Charles Bradley and Sharon Jones, and especially Leon Michels – he’s a huge inspiration to me. It makes sense that we’d eventually end up here.

Photo by Robb Klassen

I’m curious about your views on jazz culture today. As you’ve been coming up in the genre, have you been surprised about what’s being released, or how people are listening to jazz?

Alden: I feel like jazz is going in a really cool direction. We just saw it at the Montreal Jazz Festival — there’s a thirst among young people for jazz. It’s honestly surprising. We grew up playing for older people in Oregon. So it’s refreshing to see young people stoked, going out and paying to listen to jazz. In Brooklyn, I love Ornithology and the DIY club scene here.

How do you think jazz is changing with the younger generations?

Dana: It’s cool to see young people who have been educated on Lester Young, Charlie Parker, Coltrane — that whole way of playing music — and then applying it to everything they’re interested in. We’re all children of the internet now, so it’s rare to find someone who’s not into all kinds of music and culture.

Do you think this approach to music embodies the way we now experience culture in the age of the internet? Or does it go against the premise of how we now navigate the world?

Alden: I think jazz provides a counterculture to the brain rotting, short attention span, Top 40 playlist-approach to music. So many people right now are trying to make the most appeasing, digestible, smooth, short music. When you make something that’s more abstract, it’s quite refreshing to the ears.

So modern-day jazz is providing young people with a more satisfying alternative to what they’re being spoon-fed on social feeds and pop music lists?

Alden: Yeah, almost like a relief from 20-second TikTok attention spans.

Dana: I think there’s a core difference in the way we’re trying to make music, and in the way that most music is being made right now with the development technology that auto-tunes voices and perfects every detail. Recording songs has shifted from capturing a performance to creating a performance artificially. All the music we grew up loving was just about capturing a moment in time of someone’s performance. That’s what we’re trying to do: Go in the studio, do a couple takes, don’t overthink it, capture a feeling we got as a band and that’s the record.

Millions of people are drawn to your living room recordings on TikTok, which are raw and seem impromptu.

Alden: That’s how we discovered our sound as a group. Making hip-hop covers and filming them in my bedroom, we uncovered this acid-jazzy warped guitar washy-symbol bedroom sound.

@gucci_pineapple dropped Bound cover on all platforms!! #fyp #ponderosatwins #bound #cover #berklee #soul #drums #sax #vibe #mullet #parati ♬ original sound – gucci_pineapple

How did the success of those videos influence your band?

Alden: They opened some massive doors for us. We were able to meet some of our idols because of who those videos were sent around to.

Dana: But I don’t think the popularity around them informed how we played. We’re just huge music nerds and especially love covering a wide array of music we were obsessed with, like Earl Sweatshirt, Tyler, The Creator, but also “Na boca do sol” by Arthur Verocai from Brazil. Being passionate about something is contagious, and people can tell.

As fans of Madlib, MF Doom and other master-samplers, you said recently that you had a goal of making music that would someday be sampled. Does your music being used in TikTok user videos scratch the same itch?

Alden: I think it’s been cool to see a sample of the “Dragonfly” outro go viral in Latin America with inspirational soccer quotes running on top of it. I’ve also seen different rappers rhyming over the outro as well. It’s the first stepping stone to seeing the potential that a little moment from our music can have.

Dana: It’s possible to make a sound beyond genre that resonates with so many people. If you capture a strong enough emotion on a track, it can be used in so many different ways. I think that’s similar to sampling, like a Turkish psychedelic rock song being used by Madlib 60 years later while he’s rapping about his neighborhood.

@markim.jr_ 12:05 || marca ela || #neymarjr #viral #faypage #amor #marcaela ♬ Dragonfly – Dana and Alden

Your music definitely contains a range of emotions, but there’s also a joyfulness and a willingness to be silly throughout. I’m curious if this is a response to the bleakness of quarantine, when you were recording a lot of TikTok videos.

Alden: Up until 2020 I was trying to be a serious technical musician. When quarantine hit I let go of all the pressure I put on myself and just let myself have fun. So most days we would just jam for hours. We’d have friends over, get drunk and play Santana covers. It felt like connecting with the original joy we had when we were middle schoolers playing jazz for the first time.

Dana: The pandemic was a huge reset. I think when limits are imposed, that’s when humans are their most creative.

I’m curious about how you’ve been using your online presence to impact politics as well. You recently interviewed [political scientist and activist] Norman Finkelstein about the war on Gaza and it gained a lot of attention. How did that come to be?

Alden: Dana emailed him 25 times because we’re massive fans of his work for Gaza and what he embodies as a person. He lives in Brooklyn and agreed to meet up with us. I don’t think he really knew who we were, he was just down to chat. It was a real moment, going to his apartment, seeing all his books, going in his kitchen, watching him drink tea. It felt historic for us.

Dana: I remember as far back as middle school being aware of what was happening in Palestine. It’s always something that has really made me angry, knowing that this injustice is directly caused by the country that I live in. Growing up in the jazz tradition, we were taught by our mentor that any artist at any time is supposed to reflect on what is going on in the world. Especially jazz, which was born out of the oppression of Black people in the United States by capitalism and imperialism. To make jazz is to make political music.

Have you received any backlash since speaking out?

Dana: It has cost us a few opportunities, but there’s way more people that support the cause than are against it, so it’s brought us away from the wrong people and toward the right people.

Alden: We’ve met so many cool people online and in person by speaking out for Gaza. The solidarity and the community, especially in the last year, has been incredible.

How has this experience fused with your music making?

Dana: Even going back to “Quiet Music for Young People” — that album didn’t have as many direct political messages and our new album does, but the central message is still there that young people right now are aware that the state of the world under capitalism and under imperialism is not a good state. All young people have tried to find ways to numb that kind of anxiety and pain that we’re all feeling about the world. But it’s better to tune into what’s going on, take up political struggle and realize we don’t need to accept the reality that we’ve been given.

The decision you’ve made as artists to focus on capturing real moments with your music could also be seen as a political one.

Dana: I think humans are inherently political beings and if musicians and artists stop talking about what’s going on in the world we’d stop being artists.

So what’s next for Dana and Alden?

Alden: We’re preparing for our first headline tour. We’re playing in New York at the Bowery Ballroom on September 12th. And Melanie Charles will be playing with us. Come through!

You might also like