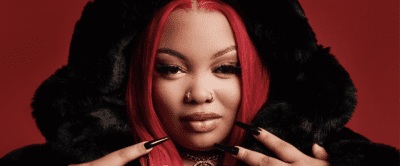

Photo illustration by Johansen Peralta

The empath: How Kareem Rahma took over your feed

The host of the viral new TikTok account "Keep the Meter Running" (among other things) talks about his very prolific 2022

Like what you’re hearing? Subscribe to us at iTunes, check us out on Spotify and hear us on Google, Amazon, Stitcher and TuneIn. This is our RSS feed. Tell a friend!

Podcaster, screenwriter, comedian, poet and entrepreneur Kareem Rahma had a banner 2022. He wrote and starred in a short film directed by Nicholas “New York Nico” Heller that debuted at the Tribeca Festival. He launched a super viral TikTok account called “Keep the Meter Running,” and he created a smart new podcast called “First.” (He also went viral early in the year when someone swiped a copy of his New York magazine.)

Today Rahma joins us on “Brooklyn Magazine: The Podcast” — the first episode of the year — to talk about who he is, where he came from, career pivots (Rahma had stints at Vice and The New York Times before going solo), and why he’s suddenly all over our feeds these days. He also lets us know what to expect in 2023.

This interview has been edited for concision and clarity. You can listen to it in its entirety in the player above or wherever you get your podcasts.

Your output has been incredibly prolific certainly last year, and I’m wondering if it’s prolific by design or if there’s just been a bunch of stuff that all happened to converge all one time. What do you think about when you think about prolificness?

There are two answers to that question. The first one is that I only started comedy four years ago, and at the time, I was about 32. Now, I’m 36 if you’re good at math. When I went into it, I was like, “I have to jam 10 years of work into five years or four years,” whatever it may be. And the reason is because I came to the game late. I’m competing with kids that have lived in New York for a number of years already, and/or already doing standup comedy or already have names, already are part of this community. And for me, I was coming into it as an outsider with no experience.

And there’s this cognitive dissonance that occurs when you do some sort of midlife career pivot or change where you want to be one thing but you’re something else. And it’s essentially like a rebrand. And I hate using corporate language like this, but it is this personal rebrand where I want people to know me as an entertainer or a comedian. And in order to do that, in order to call myself a comedian, I have to do the work. You can’t just put in your bio. And I actually remember having this dilemma where it was like a year in and I was like, “Okay, can I put comedian in my Instagram bio? What does it mean to be a comedian? Does it mean that I’ve performed? Does it mean that I am performing? Does it mean that I get paid to perform? When can I officially call myself that?”

Needless to say, it was really my identity. It was like trying to figure out my identity as quickly as possible and become that new identity. So part of the reason so much work came out in 2022 is because I think I hit my stride. I started finding my voice. I started finding my people. I started finding my community. The work that I started doing in 2021 started paying off in 2022. It’s just like the snowball effect started to pay off.

You are a comedian, as you say. You’re an “entre-median,” we were joking: entrepreneur-comedian, a writer, a poet. How do you describe yourself at parties? Is comedian the goal? Is that what you lead with?

That was always a goal. I said for a long time if I was getting interviewed or something, it was always comedian and entrepreneur or entrepreneur and comedian. And now, I think I’m shifting towards saying entertainer or just comedian. I’m not really sure. We’ll have to see. But entertainer because with the series that I’m sure we’ll talk about with “Keep the Meter Running,” it’s not pure comedy. It is a comedy series, but it’s also something else. And it’s not like a host and it’s also not like a presenter, but Anthony Bourdain was what? Like a chef and entertainer, I don’t know. That’s the vibe that is happening with that show. I’m back to square one, but at least I’m out of just entrepreneur. And now I have a new tag, which is either a comedian or entertainer or I don’t know. Dude, this is pretty much how I describe myself at parties.

Well now, you can show them your TikTok account or whatever. You mentioned the vibe and you’re the host, but you’re not necessarily the subject. What I like about certainly the TikTok series, but across the board and the stuff that I’ve seen you do is the tone. It’s funny, but it’s also, it’s human. It’s humane. It’s never cruel. It’s curious, inquisitive. What is the connective tissue between all of these projects from the TikTok to the movie to the podcast?

I think it’s for me, always been about being open and vulnerable. I put myself in the shoes of everyone else or I just have this empathic nature, and I think it’s really just this willingness to throw myself into the situations, fake it till you make it or whatever it is. Just be there and take it all in and react honestly to what’s happening around you. After I’m done with any of these things, I’m exhausted. Whether it be the TikTok or the podcast or just some viral, funny, silly gimmick, it’s always like I throw myself into it 100 percent and then I come out the other side exhausted because it does take a lot of energy to focus all emotion on one person or one thing.

It’s not just empathy, it’s bravery. In the movie, I won’t say what happens in the fountain scene, but that looks like it’s really happening. It doesn’t not take balls.

If you’re listening, you can watch the movie on Vice YouTube channel. It’s called “Out of Order.” Let’s just say that I had to do my own stunts and it was 4 p.m. on a Sunday. Let’s just say Washington Square Park is at its busiest pretty much.

Let’s take it back, find out more about who you are. You were born in Cairo, moved to the States, to Minnesota. When was that?

1989 or maybe 1990. I was ESL when I moved to the States. It’s funny. I’ve just been watching a bunch of home movies. I have them all digitized. And I’m always on this weird journey of self-discovery because I don’t really remember my past for some reason. I don’t know why. But I was watching these tapes where I’m speaking Arabic very fluently, and I always forget that I’m actually ESL.

There’s not a trace of accent [today].

Yeah. No, now I’m EFL, English as a first language. It’s wild that I came from Cairo to Minneapolis in 1989. And that’s the deal, man. Young childhood in Minneapolis, lived there my whole life.

How old were you in ’89 roughly?

I was 3 or 4. I was a young chap. I got kicked out of preschool for crying so much.

Oh, do you remember feeling any sort of, I don’t know, trauma or shock or cultural shock?

It’s just tough. You’re just thrown into a new world. And even if you’re young, I’m just like, “What are these people saying?” I have no idea what anyone’s saying. And I remember crying and just not understanding anything. My parents took me back home. I didn’t go to preschool. And I watched a lot of TV and they enforced a rule in the house, which is that I can’t speak any Arabic. And that backfired because now, I barely do speak Arabic. But I mean I can get by in an Arab country and I can survive and understand cab drivers or go to restaurants or whatever, but it’s certainly not something that I use on a daily basis anymore.

Why did your parents move?

My dad had already lived here. My dad moved to the States in 1969 directly to Minnesota, which is a very weird decision to make. But I also understand that Cairo is insane, and I think for him, he was like, “I want the American experience, the proper American experience, the cowboy experience.”

The freezing experience in this case.

It’s so cold, dude. I’m going on the 25th and I’m massively regretting it.

Would you go back to Cairo when you were growing up? Or did you have experience with family out there?

We would go pretty much every summer until about eighth grade.

Okay, so that’s a good few years. And what were those trips like for you? Were they help you understand your family, or were you just dragged along, or were you actively participating in them?

They were cool. I never really thought much of it. We would just go to Cairo every summer and vacation essentially. And it was normal for my family. And I remember I would miss my friends back home. My best friends were my neighbors. I grew up in a really idyllic neighborhood. “The Sand Lot” is how I describe it. We lived in a cul-de-sac and then it was a dead end street. So it was just open. We could do whatever we wanted at any time. There were two baseball fields. But for some reason, we spray painted bases in the cul-de-sac and we would play in the cul-de-sac, which I never really understood why aside from the fact that it was easier to get water from our parents or whatever. It was an awesome childhood.

And when I went to Cairo, I think after you get into high school, it becomes a little more complicated to get everyone away for the summer. And it becomes more expensive because everyone’s almost an adult, so we stopped going. I think I didn’t go from eighth grade to I want to say college, sophomore year, junior year. And it was a really unfortunate reason that we ended up going, and it’s because my father passed away.

Sorry to hear that.

So we didn’t go back until my dad died, and then I started going by myself. Then that became the journey of discovering my Egyptian roots, because I spent so much time in America and in the States that once I started going back to Egypt after my dad’s death, that was all about, “Let me see what this thing’s about.” I made my own friends. I would go for a month. I would hang out, and it was really fun. It was really cool.

Was there a moment at which you felt like you had a duality to you where you were both an Egyptian but also an American, a Midwesterner and eventually a New Yorker? Did that consciously occur to you at any point?

That occurred very late. That occurred after I moved to New York. Because when I lived in Minneapolis, my identity, I really felt white because it was either you were white or Black or Asian or Latino. There’s not that many Arabs. So I just felt like I was more white than anything and felt Midwestern. And I found a tape of me when I was right out of college. I had a Minnesotan accent.

Oh, that flat [Midwest accent].

Yeah. I was like, [in a Midwest twang] Oh, I don’t know, just like to hang out and get coffee at the shop.” It was really weird to think about. I moved to New York 11 years ago and I was like, “Did I have that accent when I moved here?” I must have. I must have had that accent and then over time, it just went away. And I think that’s again part of my nature of being a chameleon, is that I sink into whatever situation I’m put in.

And when I came to New York is when I started experiencing the duality. No one was ever like, “You’re so Minnesotan.” Everyone was like, “Oh, have you lived here all your life?” And I’m like, “No.” And then I started really identifying more as Arab because I saw myself be more Arab. And I was in some relationships where it felt like I was different in that way culturally, and I had to explain some of these subtle cultural differences.

You said that duality occurred to you late. Does that inform your work as an entertainer?

It’s not so front and center in my work. It’s definitely a little more subtle with little notes here and there. When I do stand up, I rarely have jokes about being Muslim or Arab, and it’s not by design. It’s just not super duper important to me. But I think that’s obviously subconsciously informs almost every decision I make, but it’s not intentional. It just is the way it is. And so for me, identity is not at the center of my work, but it’s always in the background. That’s how a person lives. And maybe for some people, it is stronger. For some people, I would say if I was Vietnamese and I owned a Vietnamese restaurant, I would probably have more to say about being Vietnamese. But I’m like, “I’m just a guy.”

You were saying earlier that you didn’t go right into comedy when you talk about your early career. But when did you know you were funny or when did you want to be funny?

I’ve always been a silly guy. I’ve always been the class clown. I was voted most likely to be in on The Real World in high school. Which I think is an honor. And I’ve always had the funny bone, but I never ever, ever thought it could possibly be a career until recently. And when I came to New York, I did improv for fun. I did classes. It was for fun. It was just something to do to keep me out of the bars, and I was really good at it. But my desire to get some money in my pocket superseded everything. And for the longest time, I only did things for money. It had nothing to do with creative output. It had nothing to do with how I was feeling. It had nothing to do about the long-term goal in my career. The only thing that mattered was to not be completely broke.

Instead of doing sports or doing a hobby, I had a job. And I worked at McDonald’s from 14 to 16. And then I worked as a busboy from 16 to 18. And then I worked as a telemarketer for a while. I just had so many jobs and I worked all the way through from 14 to now. I just haven’t stopped. The nature of the work has changed, but work has always been at the center of my life even since I was a kid.

There was this moment, somebody actually told me — because I was like, “I can’t stop. I have to keep going with this stuff. I don’t think I can take the risk.” And this person was just like, “You’re probably going to be fine. You know enough people now. You’ve done enough stuff. You can probably take your foot off the gas when it comes to generating as much income as possible at all times.” And it’s not a lot of money.

You’re talking about just making enough money to survive in the city?

And to get what I want. On one hand, you can do the starving artist route and be living in a house with seven people. And people do it and that’s great. It’s just not for me. So when I had a 450 square foot apartment with a roommate, I was like, “I’m the most successful person in the world. This is amazing. I live in the fucking East Village.” And I had to overdraft my account to get that fucking apartment, but it was the best apartment in the world to me.

But then it’s like, “I want to go upstate. I want to go skiing. I don’t want to say no to fun.” So I had to keep working as hard as possible. And then there came a point where I did feel really established. I did feel like I knew enough people in the media world. I had worked at Vice. I had worked at the New York Times. I had started my own company, and I was like, “I’m in a position where I can take a risk and I can start doing some stuff and seeing if that stuff takes me somewhere else. And I can always get a job at Spotify.” That’s always in the back of my head. There’s always Spotify or Facebook. I can always get my way into one of those things. And if not that, I can always get myself into the fucking VP of marketing at who knows? Like, fucking Delta.

You mentioned Vice, you mentioned the Times. You actually started your adult career in the ad industry. You were doing SEO and then social. It’s both were shaping the way media was made and consumed.

I got really lucky because I had an internship in college at an ad agency. And let me shout out someone who gave me my first ever opportunity, John Risdall. He recently passed away. He gave me my first internship and my first job. When I graduated, I had a job. And I walked into his office. I was really into “Mad Men” at the time and I was like, “I want to be an account executive.” And he was like, “You’re not going to be a good account executive.” He was like, “You’re in the SEO department.” I was like, “I don’t know what that is.” And he was like, “Go under this guy’s wing.” There was this guy, Jared Roy, who’s probably the same age that I am now exactly. And this guy really taught me how to work and also taught me the real minutiae of the internet, which is SEO. And it was more important than social media back then, and it’s changed drastically. But it really laid the groundwork for me to understand the back end of the internet.

And as a kid, I was super into the internet. My dad bought my first computer. We made a computer room in the garage. We were broke, but my dad spent $2,000 on a fucking Compaq or a HP because he somehow knew that this was going to be really important. I was on the internet a lot. I was an internet kid. I was learning HTML by myself. I never got good at any of these things. I was very curious about the internet. So this SEO thing was a blessing because I would’ve been a horrible account executive and I wouldn’t have learned any real tactical hard skills. A lot of that stuff has still stuck with me. I just understand the fundamentals of the internet and how things work.

Well, you’re very good at getting whatever you make seen by a lot of people, which is what SEO was designed to do. And then ultimately social.It seems like those fundamentals that you learned have been very applicable to your entertainment wing of your career. You went from the agency world, you moved to New York. And then you said 11 years ago, you went from the agency side to Vice, also at the beginning of that second chapter of Vice’s history in a way from this indie print and media company into more of a digital media company. What was your role? What was your experience at Vice?

Dude, I got so lucky. I went there. I didn’t even know what it was. I just applied for a job and somebody was like, “You have to work there. It’s so cool.” I was like, “I don’t understand what they do,” because I was used to working at ad agency where you sell products and not sell content essentially. And I was just like, “I don’t understand what this is.” But again, very lucky they were looking for someone with ad. They were just firing up the brand of content divisions, and they were looking for someone that understood social media and SEO and also advertising. And it was fucking fun, dude. I was 25, and I couldn’t ask for a better place to land in New York City, because I knew one person and that one person had just moved to New York a month before me and we lived together. So we knew no one.

Why did you move?

Just a thing that I always wanted to do. And I was like, “I’m either going to go to San Francisco, New York, or LA.” And the one guy that I lived with, Blake, he was like, “I’m moving to New York.” And he moved. And then my other friend John was like, “I’m moving to New York too.” And then I was like, “Well, at least I know someone,” so I just moved. I just picked that one. I never had the “I want to live in New York City” motivation. It wasn’t like, “I’m going to go make a name for myself.” It was just the place where I knew two people.

But I wanted to work in startups. I wanted to be at the next Instagram. I wanted to sell a company and make millions of dollars. And I remember I had an offer from some weird app that I think you take pictures. It was Instagram except just for food, and you unlock discount codes. And it was an interesting idea. And then I had the Vice offer and I brought it to the two guys that just moved here and they were like, “Yo, you have to take the Vice one.” And for the right reason: You either work at the startup that has four people or you work at this thing that’s really growing quickly that has a hundred 25-year-olds working there.

No one said the words “build out your network”, but that was essentially what happened. I got to Vice. There was a hundred 25-year-olds. For the first three months, I did not speak. I was hazed. I was the new Minnesota guy. I was definitely like, “Holy fuck, people are mean in New York.” And it wasn’t like they were bitchy. They were just cool and insular. And I remember this moment where I tried to jump in a cab with this guy from Vice to go to another party, and he had two girls with him and he was like, “Nah, dude.” And he literally didn’t let me get in the cab. And I was like, “Wow, people are very, very direct here.”

And then you end up at the Times doing growth for them, which is a tremendous job. How did you get that?

They called me one day and they were launching their video department, Times Video. And the woman that ran that department, Rebecca Howard was like, “I need to poach someone from Vice,” essentially. And they gave me a call and the money conversation came up, and my salary was literally tripled. So I was like, “I’m in. Sure.” And I remember there was some apprehension because I still didn’t understand the weight of the New York Times. And I was like, “Well, the Vice email address, at least I can get into parties. The New York Times email address, probably not so much.” But the money was worth it and it felt more adult. And it was definitely a culture shock having spent my first years at Vice and then going to work at the Old Gray Lady.

But again, it’s all about juxtaposition and high and low and experiencing all of the things that I can experience. So I really threw myself into that. It was a blast and a great learning experience, and it was an exciting time at the Times when this report had just come out, an internal report.

I remember that report. It was a massive mission statement basically to go all in on digital to double their subscribers. And they’ve pulled it off.

They did. They really, really did. I’m very proud of them because I got there literally the week or two weeks after the report was published and I was like, “Oh, this is tight.” I’m one of the new guys, and I was one of the first employees ever to have a desk in the newsroom as well as a desk in the fucking stupid marketing department. No offense to the marketing department, but it is pretty stupid. And a lot of people were not happy with that.

And I came in and did a lot of shit that was pretty insane. I published the first vertical video at the Times. I helped launch the Snapchat channel, but I also got a vertical video embedded onto the New York Times website. One day I did something really bad that I almost got fired for, which is I legitimately went to one of the coders and I was like, “Hey, can you put up a WhatsApp button on this page for me?” It was a video that I had just launched. And it was an international video, and it was so weird that we don’t have a WhatsApp button. I was like, “Can you just throw one on here?” And that person did it.

I got called in to some big room and they were like, “What is this?” And I was like, “What? It makes sense.” And they were like, “Yeah, but you can’t just literally make a change to the website.” And I was like, “Well, how do we add a WhatsApp button?” They’re like, “Well, you have to talk to the product people and the designers and the coders and the fucking editorial mast head and the blah blah blah.” And I was like, “Okay, my bad. Didn’t realize it was such a big deal, guys.” It felt like “Game of Thrones.”

So then you go out on your own. Were you ultimately fired or did you leave of your own free will?

I left to start a company because that was what I came to do, and originally it was called NYC TV. And I had been involved in something called Minneapolis TV or MPLS.TV. My friend Chris Cloud started it when I was living in Minneapolis at the time. I was like, “Ooh, this is cool art project. This is very interesting to do this public media on the internet thing.” And I was like, “Okay, that didn’t work out because maybe Minneapolis was too small of an audience. Maybe it’ll work in New York.” So I tried to do something like that here and it didn’t work here either. But the idea was to build a global network of local video channels. So like NYC TV, SF TV, blah, blah, blah.

Was this Nameless Network?

It became Nameless Network. We did a pivot. I became a CEO. I raised money. I listened to this podcast called Startup, which is about starting a podcast company, which eventually became Gimlet Media which eventually sold Spotify. That was their first podcast was called Startup. And it was about Alex who’s the founder starting Gimlet. And that’s where I learned everything about how to raise money, what a term sheet is, what investors are, how to get to them. It was sick and I just did what he did.

Is this when you do The Museum of Pizza? With what becomes Nameless Network? That was when all of these things, there was the Rose Museum, there was a Museum of Ice Cream, all these things, having the experiential moment. Were you tongue-in-cheek at all about it? Or was this like, “No, this is a Museum of Pizza.”

Nameless Network was essentially a version of Now This News where we had a bunch of Facebook pages, a bunch of video content being made. I had 20 employees at one point, which is crazy to think about.

This is all during that pivot to video era that Facebook mandated? “We want to lean in video.” And then everyone sunk all that money in the video and then everyone got laid off when Facebook changes its mind.

That’s exactly what that was. And I was like, “Oh well. Well, let’s just start a company that does that so we don’t even have to pivot. We’ll just be that right away.” And after doing it for three or four years, I just had this desire to do something physical, and I saw the success of Museum of Ice Cream. I was like, “Well, what’s the second favorite food?” Actually, the first favorite food, pizza. And I was just like, “Let’s just see what happens.” I threw up a landing page on Squarespace with $35. I remember building the website. I had nothing planned. I was just like, “What sounds cool? Pizza beach. That sounds cool. Put it on the website. What else sounds cool? A pizza cave. Cool. Put it on the website. You know what we should do? We should offer people a free slice of pizza when they come through. Put it on the website.”

All of a sudden, we put it out and I sell like $75,000 worth of tickets in the first 24 hours. And then by day three, it was $250,000 worth of tickets. And I’m like, “Oh, fuck me. This actually worked. I have to do this now.” I have five or six months, maybe four. And I just went, “Bang, let’s do it,” and went completely sicko mode on it. Essentially called friends that were artists. And I was like, “Hey, if I give you 20 grand, can you make an exhibit for this thing and share your thoughts?” And it was a fucking disaster, I’ll tell you that much. Maybe from the public standpoint it wasn’t. But behind the scenes man, it was the next Fyre Fest.

I barely scraped by, and it was at the same time the Fyre Fest was happening. And the only thing I could think about was I have a good reputation. I have to pull this off no matter what. It almost killed me. I was like, “I have to make this museum or it’s going to be real bad news for the rest of my career.” And so I did it by the skin of my teeth. There were so many things that I didn’t think about. How am I going to give every person a slice of pizza?

Didn’t you get a sponsor?

No, I paid. But I got discounts. But even logistically, how do you get pizza? Do you make it? Do you get ovens and have a pizzeria? No. You know what I did? I fucking hired drivers from Craigslist to go to Williamsburg Pizza, pick up pizzas, bring them to the Museum of Pizza, put them in an oven, reheat them, and then hand them out as if they were made at the Museum of Pizza. Really bad idea. Did we deliver on a free slice of pizza to everyone? Yes, we did. It was an indie museum. It was sick. I’m proud of it, but it gives me PTSD.

Did it achieve whatever you had hoped it would achieve?

I wanted to do two things. One, I wanted to go down in New York history as a legend. I would say it did not achieve that goal because everyone forgot about it. But I thought it was cool. I was like, “Oh, hire artists instead of fabricators. That will be a real museum dedicated to pizza.” Museum of Ice Cream is more of a Instagram pop-up. This is more of a real museum with pizza art. And a lot of the people that came were like, “I wanted an Instagram museum, not a real museum.” So it didn’t achieve the goal of going down to New York history. And then the second goal was to make money, which I lost, actually. So I would say it didn’t achieve either goal.

That was a turning point. That was 2018. Around the same time that I was like, “I’m cosplaying as a CEO. I’m cosplaying as a businessman. I’m not even good at this. I can barely do it. I can get it done, but I’m not doing it great.” And that’s when I started publishing poetry on my Instagram page and pivoting from entrepreneur to artist. And I got a lot of people that were super supportive of me. I pitched a book to Pioneer Works. They said yes. We made this book called “We Were Promised Flying Cars.” That came out. I started doing readings and I noticed that people would laugh at some of the poems because they were funny, or I would start doing bits in between the readings and I was like, “Oh, that is the feeling that I desire.” I like the laughter. I was like, “All right, I’m not a poet anymore. I’m a comedian,” and bada bing, bada boom.

Well, you’re still an entrepreneur. You’re still cosplaying as a some kind of CEO. You launched a podcast company, you teamed up with Andrew Kuo and you are doing stories about people of color. You are “amplifying stories and voices that accurately reflect the diverse makeup of our country.” I think that was from the press release. First of all, I really enjoy the podcast that you host, “First.” It’s about people who have been the first at their thing. I love the Omar Sharif episode with Ramy Youssef. Did you guys know each other beforehand?

Yeah, we’ve been friendly. I caught him right before he did the TV show and I was like, “Oh cool, another Egyptian comic.” He was in the scene, but I remember I DM-ed him a long time ago and I was like, “Hey man, I’m thinking about making the pivot to entertainment.” And he was really nice to me and was supportive. And then when I had the movie at Tribeca, he sent me a really kind message and I was like, “Oh, he’s been paying attention. That’s cool.” I don’t want to say that there’s no era of Egyptian comics. There are. But it’s hard to find someone who has had the impact that he’s had in recent years. And he’s really opened the doors for a lot of people. He was awesome.

His show is tremendous. I love it. The production value of your podcast is great. You’re doing something right.

Shout out SALT Audio. They do all the post-production for that. They’re a great company. I’ve really enjoyed working with them. Doing a podcast like that is a lot of work. We decided to make it saucy and throw sound on there and music and sound effects. And the point of the show was to make the subject that is interesting but as difficult to either talk about or have fun with, to try to make it a little more entertaining. I think we did a pretty good job with that.

And then there’s “Keep the Meter Running” which started in October. And racked up millions of views out the gate on TikTok. I think the idea is so brilliant. I’m jealous that you had the idea because it’s so crystal clear and it’s great. You walk up to a cab driver and say, “Take me anywhere you want to go,” And then you follow them around. And in my experience, I grew up on the West Coast. When I first moved to the East Coast, I lived in D.C. and I remember talking with cab drivers. And they were always the most fascinating conversations. They’re like, “Oh, in my country, I was a pediatrician. And now I have to go to med school all over again.” And those stories were endless. Where did that spark? Where did you have that idea?

I have always been very attuned to what cab drivers are saying, regardless of where I go and travel. I’m like, “You know the secret. Let me know the secrets.” And not just the secret of the city, but the secret of life. Because it’s such a hard job, and they meet so many people and it’s just like they’re Zenned out, they’re cool. I’ve always had a fairly intimate relationship with my cab drivers. I guess it really depends on my mood, to be honest with you. I’m not a pleasure in every cab. Sometimes I just don’t want to talk at all.

And some of them are crazy too. I’ve definitely had some not-wise-old-soul cab drivers. I’ve had guys give me insane advice about women or whatever.

I took a cab from Manhattan to Brooklyn once, and I was having a really, really rough day and he just gave me some fucking terrific advice and made me feel really calm. And it wasn’t the end of the world. Talked to me off the ledge. And at the end of the ride I was like, “Hey man, do you want to keep hanging out?” And he was like, “Yeah, but I got to keep the meter running.” And I was like, “Oh. Well, sorry I don’t have any money.” I remember I got another cab and I wrote the words “Keep the Meter Running” down in my notes app and I was like, “This is a good idea, but it’s obviously expensive so I can’t do it yet.” But it was always something I really wanted to do. And I revisited it a lot. And then the right moment came where I found an amazing producer, Adam Faze, who was like, “I want to do this with you.” And so we did it.

You pay all the cabbies. Some of the bills are over three, four, $500. Where is that funding coming from?

This company called Mad Reality has co-produced and funded the first season.

Over that first season, you’ve had Abdur. I think that was the first one. He takes you to lunch at a Pakistani deli in Jackson Heights. You played soccer with a Tibetan cabby named J.J. You went to the U.K. You went on a helicopter ride with one cabby. Do you have a most memorable? Because all of them are pretty memorable in their own right.

They’re all amazing. They’re all so fun and there’s not a most memorable. The most unexpected fun I would say was with Vinny who took me to Buffalo Wild Wings. And I remember my initial reaction was like, “Oh, this sucks.” And then it was literally half a second where I was like, “Actually, this is going to be fucking hilarious and amazing.”

Do you keep in touch with any of those guys?

All of them. I had J.J. over at my house for tea. I just put George who’s the Ghanaian that took me to my favorite food that I’ve had so far, Papaye in the Bronx. I just hit him up literally on Sunday to be in a movie that I was making, a feature film.

You’re making a film?

Well, it’s already done. It was a crazy month. We did a feature film in six days.

Do you do this with Nicolas Heller again?

No, no, no. This one’s more of a drama. I co-wrote it and co-produced it and co-star in it with this wonderful actress, Mary Neely. And it’s like a very classic New York walk-and-talk style film that is reminiscent of Before Sunrise. That’s the vibe of it. I think it’ll be hopefully this year.

You’re going to shop it around the festival circuit? Is that the goal Find a distributor maybe?

Exactly. It’s a movie that should have cost a lot more than what we did it for, which is why we did it in six days. But I would say that it should have been 12 days. But the budget that we got was six days, so we were like, “Let’s fucking do it.” And we had an amazing team, 30 crew, an amazing DP, Jeffrey Lee Cohen, amazing director Jeffrey Schroeder, amazing producers Sophia Lauren, Pearl Wa, and Daniel Sowell, and just a radical time.

How did you and New York Nico team up in the first place? How did “Out of Order” come about?

He hit me up, and we’d always been following each other. We were followers of each other when he had 10,000 followers. And he would actually hit me up when he was doing docs on Vimeo and YouTube, and he would ask me to share them on Nameless Network when I had all those pages with millions of people. And I was like, “Sure, no problem. I don’t care.” Usually we charge for that but I was like, “He’s an independent creator. We’ll put them up no matter what.” And when the pandemic was leveling out a bit, I was in L.A. and he hit me in a text that was just like, “Hey man, I think you’re so funny. Have you ever wanted to make a movie?” And I was like, “Of course. That’s always the goal.” And he was like, “I have a premise and an idea, but I don’t know how to write films. Would you consider doing it?” I was like, “Of course.”

And I took it very seriously. The minute he said it, I got off the phone. I was like, “Holy fuck, this is about to be a huge opportunity.” And I literally started writing that day, and I had a draft to him within 72 hours and he was like, “I love it.” We obviously continued the back and forth for a few months. But once we locked the draft, we found the money right away. We found a very generous funder, executive producer, and then we just made it.

And it’s great and just about every character in it is someone in the in the Nicoverse, yeah. So you’re in Brooklyn. Where are you?

North Bed-Stuy. If I cross the street, there’s Bushwick.

What’s a typical day for you? Or if you were to recommend to people who are visiting your hood, where do you tell them to go?

On special occasion mornings, like a lazy Sunday, I’ll go to this coffee shop called Marcy & Myrtle where they have wonderful coffee as well as terrific breakfast sandwiches. The egg croissant is my favorite. And then for lunch, I like to go to either Natural Blend for a smoothie or Brooklyn Blend for a smoothie. I usually always have a smoothie for lunch and I usually go to one of those two places, Brooklyn Blend more than Natural Blend. And then for dinner, I love Trad Room. It’s just like this Japanese restaurant and more Southern and Stuyvesant Heights. That’s definitely my favorite meal, I think, for dinner in Bed-Stuy. I’ll go to, what’s that bar called? It’s a great bar. It’s my favorite bar. I don’t remember the name. That’s weird, right? Ooh, also Winona’s has one of the best breakfast sandwiches. Winona’s great … What is that fucking bar? Coyote Club.

I kick around, take walks, hang out at Herbert Von King. Otherwise, I just chill. I love Bed-Stuy. There’s so many people in the neighborhood that I say hi to and that have become my friends. Like I said, I love Brooklyn because it feels like a small town. I feel like that Bed-Stuy even more so than any other place I’ve lived in New York feels really like a small town.

Check out this episode of “Brooklyn Magazine: The Podcast” for more. Subscribe and listen wherever you get your podcasts.

You might also like