Muniz, left, and Finger

At The Mutt Museum, upcycled fashion shares center stage with the art

Collaborators Antonio Muniz and Sam Finger have created something that’s “not just a clothing brand and not just fine art”

Upon entering 7 Dunham Place, visitors are met with a conceptual gallery space that houses both visual art pieces and upcycled clothing. Between walls covered in gestural paintings and colorfully embroidered denim for sale, lies a purpose.

The Mutt Museum, which opened in May, is the brainchild of collaborators Antonio Muniz, an architect originally from Mexico, and New York-based designer Sam Finger. Both wanted to create an artistic community within their new home of Williamsburg and foster a sense of responsibility among their visitors. Acting as both a fine art gallery and retail space, with price points to match the bespoke nature of the work, The Mutt Museum explores the intersection of art, fashion, and consumerism. The name itself is not only a play on The Met Museum (in September they threw a “Mutt Gala”), but a direct reference to their melding of different media

Muniz and Finger create large paintings with smoke on canvas — a technique called fumage — and display a range of expensive upcycled luxury pieces, such as Prada totes, to more affordable ready-to-wear pieces, all with the underlying theme of breathing new life into the old.

Brooklyn Magazine sat down with Muniz and Finger, who teamed up in 2020, to discuss this type of circular fashion, shifting the industry from the inside out, and bringing it all together in Brooklyn.

In what ways do both of your different backgrounds, upbringings, and experiences inform your designs?

Muniz: I’ve always had a passion for art as an architect and as a painter. Collaborating with Sam has taught me to read the body differently when also applying art to it. There are different structures and guidelines for how to make something wearable. I learned a lot about how to create compositions within a body of work. Instead of treating the art on a flat canvas, I had to look at a three-dimensional body. That was challenging for me.

Finger: Antonio’s art is so gestural and it has these really large, dramatic movements. What I’ve learned from a design perspective is how to take those dramatic gestural movements and infuse them into every piece. So I really learned how to push things to extremes, as a painter would, but on a piece of clothing. Which has been really exciting for me from a design point of view to see, “Oh wow, you can push that so much further than maybe what you see in the trends at the time.”

Sam, where did you get your passion for vintage — and what do you think about when you think about circular fashion?

Finger: I grew up in New York City, and the genesis moment of vintage coming into my life was being sent to boarding school for being a little bit of a rebel. I needed to get suiting, ties, and stuff like that but I really didn’t like the idea of wearing these preppy outfits. I had never really worn clothes like that. So I went to Tokio7 in the East Village, which is crazy because it’s still there but that feels so long ago now. I bought vintage designer belts and clothing and mixed them all together with my uniform. That was when I really started getting into the identity of bringing vintage into my style and aesthetic and who I felt like I was. Then when I got into designing, I saw how much was wasted and there was always this idea of new, new, new. And I actually found myself still wearing vintage clothes all the time. So that’s when I started seeing the possibility to mix the two together.

Antonio, what does fashion design allow you that painting or architecture do not?

Muniz: Architecture, in a way, is a very rigid form of expression. The arts allowed me to break away from it. Now, planning a garment, it’s very calculated — it’s kind of a mixture of both.

By merging those two things, as you said, you create something new that hadn’t existed before. You started experimenting with fumage and now use it to create extraordinary pieces that are completely individualistic. As fire is thought to be regenerative, in what ways does smoke reinvent or elevate your pieces?

Muniz: Smoke — I always say it’s a universal language. I feel like it gives the viewer or the observer the freedom to interpret however they want, regardless of what emotional state they’re in. And that creates a unique relationship between the object and the observer and they are able to make their own story with that. I always say that smoke is multidimensional, so regardless of if you’re seeing the same pattern as someone else, maybe a month later, it’s going to show you something new — an image that you haven’t seen.

Aside from implementing fumage, another large tenet of The Mutt Museum is sustainability. Many of your pieces are upcycled or reworked — what is the key to creating a wearable, yet unique, reworked piece?

Finger: In both womenswear and menswear there is a box that you are trying to defy. You want to try to get a little bit outside of that box that you’re stuck inside with the help of upcycling. But you want to keep the framework of the garment the same. That’s what I find exciting and that’s kind of my approach to upcycling.

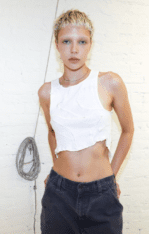

The Kitsugi tank, $150 (Courtesy of The Mutt Museum)

It’s really amazing to see an upcycled piece where the function is kept intact. That’s the beauty of a lot of your pieces. They’re so wearable and then you look at those fine-tuned details and you notice the artistic elements as well, especially with your reworked tank tops.

Finger: For those, it was really about taking this thing that had a meaning and a history and redefining its meaning with the technique we used. We were inspired by Japan’s broken pottery, the Kintsugi technique. They take broken pottery and put it back together with gold leaf to emphasize the broken parts. It’s the idea that the broken parts are beautiful and they have history. That history is the meaning. So for us, it was about taking this broken thing, the “wife beater,” and giving it a new meaning of more fluid, feminine energy.

How do think about fostering a more considerate, resourceful environment in the realm of fashion? How can designs like yours begin to shift the narrative?

Finger: A big one is getting people to shop differently to begin with. The more meaning is put into apparel for people, the more they’ll shop in a meaningful way. Right now, it’s about the quickness of trends, and that influences people to throw things away and create more waste. I feel like when there’s a story, a history with a garment, people will tend to appreciate and hold onto it longer and maybe even recycle it as well.

Telling those stories seems to be the heart of what you guys are doing when you are combining art and pieces that have these really deep intentions.

Finger: I also love the relationship that it creates with the customer. We have such intimate experiences with our customers and we really get to know them. It creates more meaning for us as well.

Why did you choose Williamsburg as the location for this space and what does being a part of Brooklyn’s creative scene mean to you?

Muniz: Well, it was destined. We had other places to be, but all of them fell through. So, in a way, it was a gift. That’s how I see it. I’m just getting to experience the area since I’m pretty new to New York. Sam did know the area, once I showed him the space, and he was like, “Oh my God, that’s an amazing area.” I wanted to create that community, and once we were provided with the space we wanted to welcome everybody around it.

What impact do you hope The Mutt Museum has on the local community as well as the wider fashion and art communities?

Finger: For me, the biggest goal of The Mutt Museum is to grow the community larger and to create an environment that fosters the creativity of others pursuing similar goals in the industry. I want to be a space that fosters ethical practices and promotes an interesting artistic vision.

Muniz: The way we approach our garments, it’s all about embracing change and trying to do it with the least resistance possible. We all want change but at the same time, we fear it and push it away. Presenting those pieces welcomes people into experiencing and embracing change.

You might also like