Beth B, Scott B, 'Letters to Dad,' 1979, video (detail) Collection Beth B & Scott B / Kino Lorber

No wave’s new wave

The very brief, very downtown New York, cultural movement gets its due in a Paris retrospective

How does one create an exhibit about a quintessentially New York movement that, at its core, defied categorization? If you’re in Paris of all places, you’ll get your answer.

Through May 15, the Pompidou Center in Paris is hosting a radically original exhibition devoted to one of the more obscure — if not noisiest, shortest-lived yet highly influential — music and visual art movements in New York’s cultural history: no wave.

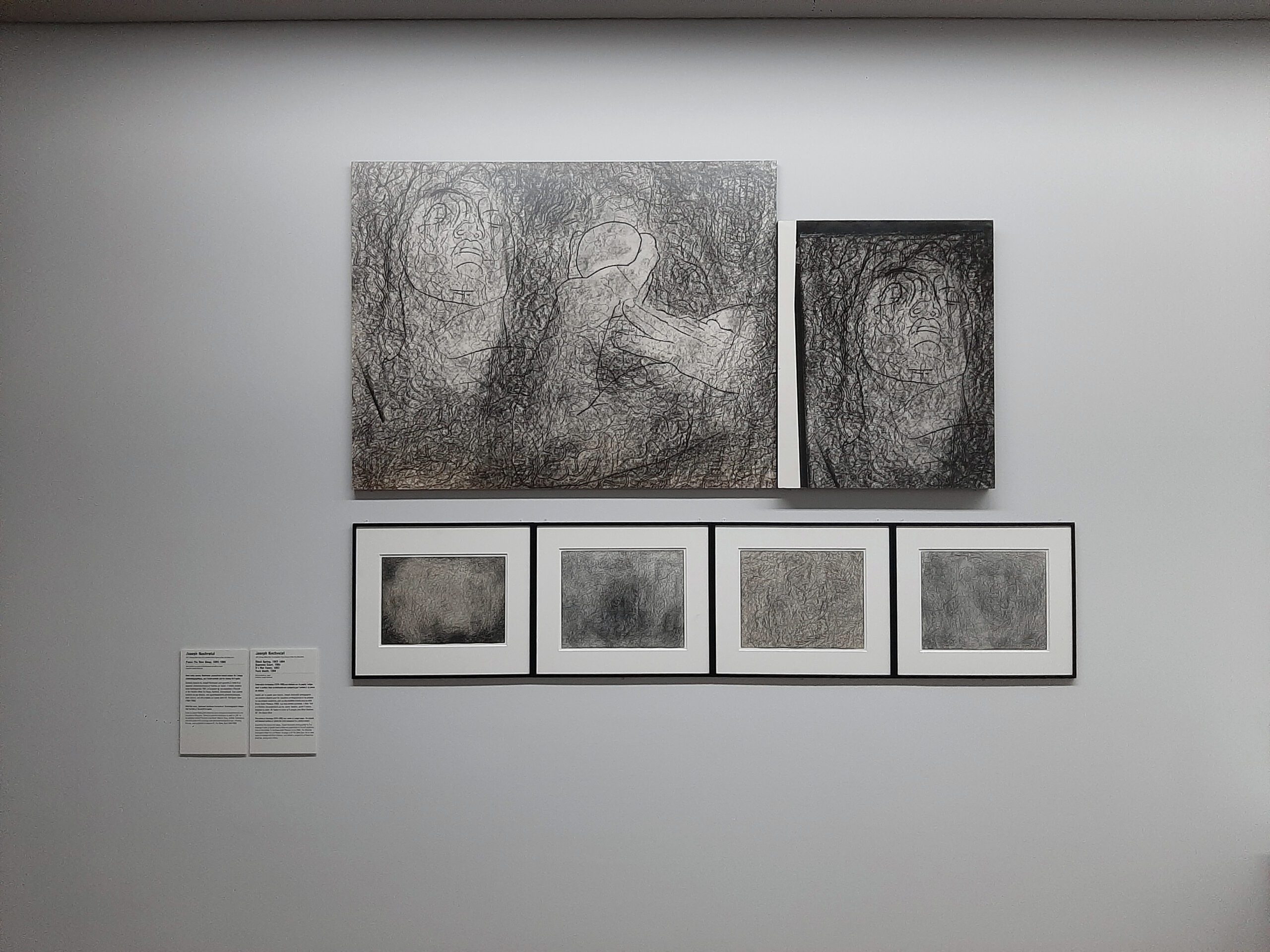

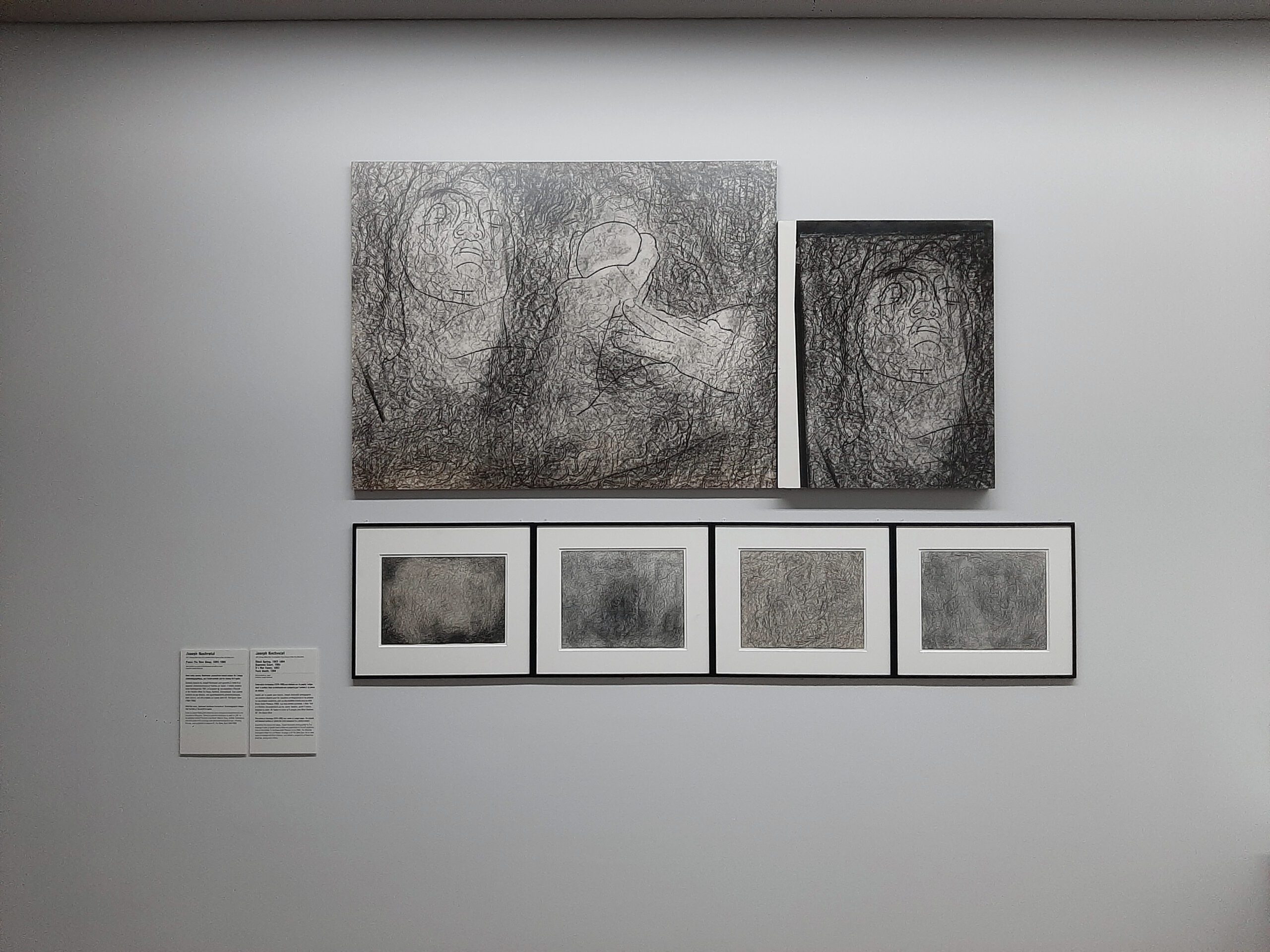

“The exhibition,” explains post-conceptual artist Joseph Nechvatal, “articulates for the first time some of the connections between no wave music, cinema and the visual art community in New York City in the late-1970s to the mid-1980s.”

With its harsh, rhythm-based sounds and nihilistic lyrics, no wave was a fresh and innovative scene among avant-garde artists and noise musicians. Visceral, raw, liberating, no wave is considered New York’s last cohesive, experimental, avant-rock movement.

Born in the low-rent district of Manhattan’s lower East Side in 1978, no wave lasted only until 1981. But its influence has proven more long-lasting than the movement itself. Coming from a variety of artistic fields, no wave was an avant-garde art movement rebelling against the status quo and shaking up the art world with their boundary-pushing antics.

The Pompidou Centre’s presentation borrows its title, “Who You Staring At?” from an album by John Giorno and Glenn Branca. The question refers to no wave artists’ defiant attitude and determination to deconstruct the conventional gaze.

Superbly organized by art historian Nicolas Ballet, The Pompidou Center’s “Who You Staring At? Visual Culture of the No Wave Scene in the 1970s and 1980s” consists of a sweeping variety of media, from dance, opera and music to the visual arts. This ensemble of multidisciplinary practices includes New York-based choreographer Karole Armitage and composer-musician Rhys Chatham’s wonderful no wave ballet, “Drastic-Classicism”; a series of videos and films by renown, pioneering filmmaker Beth B, including her award-winning video, “Belladonna,” and “Letters to Dad,” produced in collaboration with filmmaker Scott B.

There are pinhole photographs by musician-photographer Barbara Ess, drawings by Raymond Pettibon, a slideshow of assembled drawings by post-conceptual artist Joseph Nechvatal set to the music of Chatham’s “Die Donnergötter,” plus Nechvatal and Chatham’s “XS: the Opera Opus,” and so much more.

Adding to the exhibition is a series of displays including an X Magazine poster, one of the rare publications to promote the different aspects of the no wave scene.

Ballet has also invited other Parisian venues to partake in this exciting exhibition including the Cinema L’Archipel, an alternative film movie house, and The Film Gallery, where one will see a collection of no wave flyers and Beth B’s seminal documentary, “Lydia Lunch: The War is Never Over.”

Rhys Chathan at the Pompidou (Herve Veronese)

‘You can’t imagine the freedom’

The term “no wave” was first used as a tongue-in-cheek pun on the then-popular “New Wave” movement, but it quickly came to symbolize a form of resistance against being pigeonholed or categorized, allowing musicians and artists and filmmakers to have a greater freedom of expression.

“You can’t imagine the freedom that we had,” says filmmaker Scott B. “We’d take over buildings to have art shows. We dumped a car in the East River as a part of a film, and published photographs of it in The Soho Weekly News.”

But no wave was not just about creating something new, it was also a survival guide to the chaos of New York City in the 1970s nicknamed, “Fear City,”

It was a tough place. The city was bankrupt, the tenements were crumbling, the streets were dangerous and poorly lit, the Bronx was burning and the rats far outnumbered the people (some things don’t change). In this context, no wave was a commentary on the city’s dire situation, but also a beacon of hope, a movement that refused to be beaten down by the darkness.

By taking something that was broken and making it whole again, taking something that was dark and making it light, no wave created a new reality.

But how did this brief movement create such a lasting impression? Perhaps the answer lies in the single word: “no.” A word that could hardly be smaller, yet, like the no wave movement itself, it is a symbol of all the possibilities in rejection of the tropes of punk, from which it sprang.

“I remember seeing people like Patti Smith and the Ramones, who could barely play their instrument, getting up on stage and performing,” recalls Rhys Chatham. “It freed us to perform an instrument without needing 10 years of studying the instrument before you could play in a technical way.”

In other words, no wave showed that art could be raw, unpredictable, and even a bit dangerous. So dangerous, in fact, that, as Chatham tells it, when he and his group performed in such clubs as CBGB, the audience would throw beer cans. “And that was if they liked the music.”

While it’s true that no wave was largely unknown outside of the New York art and music scenes, it will forever be remembered as a pivotal moment in musical history. “Without no wave,” says Chatham, “we wouldn’t have indie rock and bands like Nirvana.”

But it wasn’t just about the sound, no wave also had a significant influence on independent film, fashion and the visual arts, from the work of designers like Vivienne Westwood and Comme des Garcons — who incorporated unconventional materials, bold patterns and unconventional silhouettes into their designs — to the independent films of Beth B.

“Films by Eric Mitchell and Vivienne Dick testified to the existence of a no wave cinema, which emerged in New York clubs and screening rooms such as the Millennium Film Workshop, The Collective For Living Cinema and the Bleecker Street Cinema, showing works by Amos Poe, James Nares, Beth B. and Scott B.,” says Ballet.

Vivienne Dick (Herve Veronese)

It was a movement that rejected the idea that art had to be beautiful or polished. Through its bold, often abrasive, experimentation, and fearless subversion of norms, no wave shattered the boundaries of what was deemed acceptable in popular culture and art, thus forging a path of its own and defining a new standard of artistic expression.

Or, as The New York Times put it: “Despite its brief, blippy existence, no wave has had a broad and continued influence on noisy New York bands, from Sonic Youth and Pussy Galore in the 1980s to current groups like the Yeah Yeah Yeahs and the Liars.”

The Pompidou Center’s killer exhibition offers visitors a chance to get up close and personal with the artists, musicians, and filmmakers who defined the movement. The Center’s dynamic and engaging setting is the perfect venue for soaking up the brilliance of an artistic movement that just won’t die.

Joseph Nechvatal, ‘Peace the New Sleep’ (Nicolas Ballet)

You might also like