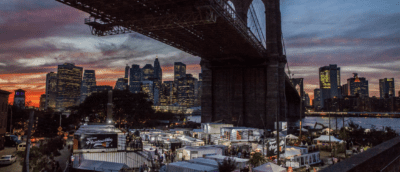

Photo illustration by Johansen Peralta

‘Wire’ actor Gbenga Akinnagbe’s new role: Saving a landmarked magnolia tree

The actor discusses his dynamic career on screen and stage, writing, racism and his prolific activist efforts in Bed-Stuy and beyond

Like what you’re hearing? Subscribe to us at iTunes, check us out on Spotify and hear us on Google, Amazon, Stitcher and TuneIn. This is our RSS feed. Tell a friend!

Gbenga Akinnagbe is a writer, activist, Brooklynite and — if you already know who he is, you know we’re burying the lede. Akinnagbe is a powerful actor, perhaps best known for his role as Chris Parlow, the terrifying assassin on the HBO’s “The Wire.” But to leave his resume there would be doing him (and all of us) a tremendous disservice. He has starred alongside Philip Seymour Hoffman and Laura Linney as an orderly in “The Savages” and returned to HBO as Larry Brown in “The Deuce.” He can currently be seen in FX’s “The Old Man” as a hit man sent to kill a former CIA operative played by Jeff Bridges. Oh and he also played the doomed Tom Robinson in Aaron Sorkin’s smash adaptation of “To Kill a Mockingbird” alongside Jeff Daniels’ Atticus Finch.

But Akinnagbe thrives in another role as well. A longtime Bed-Stuy resident, he is deeply rooted and active in the community. Right now he is engaged in a campaign to save a 140-year-old magnolia tree on Bed Stuy’s Lafayette Avenue, an extremely rare thing to find thriving this far north. It is Brooklyn’s only living landmark. Behind the tree are three historic row houses — home to the environmentalist Magnolia Tree Earth Center. The buildings and the tree were all saved from demolition in 1977. Today, however, all of them are at risk again as the community center can’t afford overdue fines from the city and urgently needed repairs. Akinnagbe has joined the efforts to save that tree and preserve a precious and endangered corner of his community.

Akinnabe is this week’s guest on “Brooklyn Magazine: The Podcast.” Don’t worry, we’ll talk about the Wire. But we’re going to start with the tree, what it means to the neighborhood and what its threat represents at an existential level. We’ll also talk about how he came to Brooklyn in the first place. Akinnabe is a child of Nigerian parents, the first in his family to be born in the States. We talk about his career as an actor from “The Wire” through “Mockingbird” and we will talk about his other philanthropic efforts on behalf of the Trayvon Martin Foundation, Planned Parenthood and more. For someone who can play scary very, very well, Akinnabe is compassionate, empathic, light and funny.

This interview has been edited for concision and clarity. You can listen to it in its entirety in the player above or wherever you get your podcasts.

It occurs to me that you are the second actor from “The Wire” that I’ve had on this podcast, and neither conversation really was about “The Wire.” We did a live podcast with a couple of the cast members of “Flatbush Misdemeanors” and Hassan Johnson was on that panel. He is hilarious.

He is. He’s amazing. I produced this movie called “Newlyweeds,” and he was in it and he was one of the best parts of it. He was hilarious.

Let’s start with the Magnolia Tree Earth Center. Tell us a little bit about this amazing tree. It’s this 140-something-year-old magnolia tree, which is itself weird that it’s in Brooklyn, that’s in Bed-Stuy. It’s at risk today. And there’s this amazing woman, Hattie Carthan, who saved it in the ’70s. I’ll let you take it from there. What do you want people to know about this tree and this space that’s in your neighborhood?

This center is our cultural heritage. It’s these three buildings that were going to be torn down 50 years ago, including, as mentioned, the magnolia tree. And it’s a particular type of magnolia tree. It is has no business surviving this far north. It has these beautiful big white flowers. And Hattie Carthan saw that it was going to be torn down and she galvanized the neighborhood, galvanized Brooklyn and got the tree and the three buildings behind it saved and landmarked, and then created what probably was the first environmental nonprofit in Brooklyn or Bed-Stuy. And they started to teach people in the neighborhood about green spaces back in the day, about the land. And there was a farm that was created nearby, named after her as well here in Bed-Stuy. She left this legacy that still persists today. There’s all types of great programming that happens there. There’s OSHA training that happens there. There’s all types of cultural classes that happen there.

‘Magnolia Tree Earth Center’ by Hobo Matt is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

It’s 50 years this year, right, that the center was established? And this is right at the dawn of environmentalism creeping into the cultural consciousness. The tree was designated a living landmark. Help me understand what that means. What’s the window? What is the crisis right now?

The tree’s landmarked, the buildings are landmarked, and the buildings are in disrepair and fines with the city are building up. Brooklyn is full of predatory investors just looking for an opportunity like this where these cultural institutions slip into their hands and there’s no reason why we need to lose these buildings. So, we’re raising money with the campaign. The campaign was launched maybe two weeks ago now.

Early February. Yeah.

We need to raise $350,000. The last time I checked it was on course, but we need everyone, everyone who cares about the environment, everyone who cares about Brooklyn, and everyone cares about legacy. And even if you don’t care, just donate. Once the fines are cleared, the nonprofit will have access to other funding that will help stabilize the nonprofit and will continue to give to the community. These are direct services to the community. Programs like this are vital.

This center is vital in itself, but it is part of a bigger story that’s happening in Bed-Stuy right now. We had that historic mansion on Willoughby Avenue that was torn down last year, even as they were waiting for landmark status to pass.

It was torn down? Can’t even go on that avenue now. I can’t even go on that avenue.

This is a broader issue in Brooklyn across the board, but Bed-Stuy specifically. How long have you been in Bed-Stuy now? What is your relationship to the neighborhood?

I’ve been in Bed-Stuy since, I think it was ’07 or ’08. I love it. This is home. I used to be one of those people who prided themselves for never living under 116th Street. I was like, “I’m not going to do that. Everybody’s going out to Brooklyn.” Like, “Nah, son, Washington Heights, Harlem, Spanish, Harlem, today I die,” and then I had to move, which is common. Almost every conversation in New York has to do with moving or everyone trying to find a new spot or a better spot, because living is such a topic of conversation here. Because it’s difficult and I had to move. I looked at places all through Washington Heights, but then I looked at one place in Brooklyn. I said, “Let me just check this out, this one place.” And I’ve been here ever since. I love it here. This is home.

You’ve been pretty active in the community since you’ve been here, and I’ve been hearing about your efforts at least since peak Covid, but you’ve done work with the Weeksville Heritage Center, you’ve got your own company, Liberated People that sells hoodies to raise money for the Trayvon Martin Foundation. You have a partnership with Planned Parenthood. When did you become socially active in this way? When did you start engaging in either the world or the immediate community around you?

Giving back has always been a priority fOne of the things I love about Brooklyn is that you can give back. The barriers of entry are not insurmountable. If you want to go and help your community, you have just to go out to the corner and do something with your community. Our politicians are super accessible, our council people, this is a priority to us. There was a great spot back in the day called Bread Stuy.

I remember that.

Lloyd Porter. He was a pillar of our neighborhood.

Was he a Covid casualty? I remember when they closed.

Lloyd was awesome. He was one of the first people that we lost to Covid, and so back in the day, him and his wife Hillary, they had Bread Stuy and they would have all these community events there and when I saw this, how it got the community together, the kids, everyone, and then when Bread Stuy was having issues and everyone galvanized to save it, he just spoke to me. It’s like, “This is what community is, this is all we have is each other, so let’s do the best we can.”

Back to the Magnolia Tree Earth Center, what’s the status there? If someone’s listening today and we’re like, “Wait, there’s 140-year-old tree that you’re going to chop down, how can I help?” I know there’s a GoFundMe. You’ve raised something like $34,000 towards. You have a goal of $350,000. People can contribute there. What else can people do?

They can give $350,000 start there! It’s a great organization. You can help out with money. You can help out with volunteering your time. You can help out with volunteering your ideas and efforts to spread the knowledge of this organization and its efforts. You can spread the GoFundMe, you can come and take classes there and maybe teach classes there if you have a skillset that you think the community will appreciate. So, just a range of classes that are being done there. So, just show up. And if you have access to foundations or organizations that may want to give money to a grassroots organization that’s been in the community for a long time, help facilitate those connections.

You grew up in D.C., right? You were the first in your family to actually be born in the States.

My sister was born in Nigeria. My parents are all from Ondo Town, Ondo State. It’s like four hours I believe, outside of Lagos. Yeah, I was the first one born here.

Have you been back, or do you go back?

I didn’t grow up going there, but as an adult I’ve been back. I love going there. My time to go is usually during December, like the holidays, but I’ve been working consistently through the holidays for the past few years, so I’m long overdue. I love going back and recharging and there’s nothing, absolutely nothing like being in a Black nation. I just love going back, but also reconnecting with my roots. There was a lot. I’m still discovering who my family is and about my Nigerian self, and so I love going back because of that.

You were working on a movie that took you away from that trip this year? What are you working on?

I don’t know how much I can say about it. I was about to say “dope.” It’s tragic, but it’s also dope. It’s based on a true story on a book called “The Short and Tragic Life of Robert Peace” written and directed by Chiwetel Ejiofor who’s also in it. It’s a really important story and Chiwetel, it’s a passion piece of his, and I know they were supposed to start when Covid started.

Talk about growing up. You’re in Silver Spring [Maryland], right? You wrote a piece a few years ago about how wrestling saved your life as a younger man and that was before acting. You got to acting kind of late.

Yeah. I got into wrestling late. I didn’t start wrestling till my junior year in high school. I was in and out of different schools, and so I wasn’t allowed to do after-school activities, and then finally I had mainstreamed into my homeschool for a couple periods. So I was allowed to do an afterschool activity that went in for the wrestling team. I was very fortunate and then I got recruited D1 the next year, and so that definitely changed the vector of my life.

And then, acting came even later. You were working at AmeriCorps? You were working with the government in some capacity.

The Corporation for National Service, it’s the headquarters of AmeriCorps, Teach For America, NCCC. It was created by Clinton years ago. It’s a federal agency. It’s the headquarters of the National Volunteer Service programs, so it’s like programs like the Peace Corps, but domestically, and I worked in their congressional affairs department. I really love knowing how systems work and how people in governments work, and so I was very excited and then I found out how systems work and people in governments work. I was like, “Oh, this is it.” Okay.

What was the most dispiriting thing that you saw, or is it systemic?

We blame politicians, and rightly so, for being hypocritical and the system for being flawed and full of bureaucracy. But the truth is, as citizens, we maintain a system where we don’t allow politicians to be honest. If a politician stood up and told us the truth, we wouldn’t vote for them or award them with power. They’re flawed people because we are flawed people. They’re humans, but they go up and they pretend that they’re not human and they pretend that they’re above all types of immoralities and so on, and then we’re flabbergasted when George Santos comes around. We encourage and reward the best liars.

That’s almost empathic towards the politicians, but also introspective at the same time. I wish more people thought that way. Did you ever do AmeriCorps? Did you do Teach For America or anything like that?

No, no. I considered it when I was thinking about leaving the job, I was a legislative assistant. I was just helping out making copies of stuff and sometimes I’d go to the Hill, but I considered it, going in to do AmeriCorps. That was more exciting to me, just being on the ground and helping teachers or helping to rebuild libraries after floods and stuff like that, but no, I never did.

So you’re disillusioned. You decided to go into acting, you’re in your early 20s at this point?

Yeah, I’m 21, and so I got curious about it and I started buying books, started researching it. I don’t think I was actually trying to become an actor. I just got fascinated by this world I knew nothing about. The more I found out about it, the more I wanted to find more, and so I bought books. I found out that there are auditions in the area and then I was like, “Oh, let me submit myself.” I found out you needed a headshot and monologues. I remember going out for this audition and I saw that it was for a movie that Spielberg was doing, and I saw the title. I’m like, “Oh, wow, this is so cool. Spielberg is making something like for Black people and involving a lot of Black people.” I went to the audition and it was low level. I think if I did get it, I would’ve been an extra.

I had no idea of any of that. I was just excited, and they had dummy sides, if I remember correctly, which were not the actual sides from the movie. Just mixed sides made up for the audition specifically, and so I did it and the paper was shaking in my hand. It was so wild. It was exhilarating and then sometime after that, maybe a year or so after that, I saw the movie, but it was coming out and I went to go see the movie and I sat there in the theater, and I was totally blown away when I realized that “Minority Report” had nothing to do with Black people.

[Laughing] I was going to ask what the movie was, but I had a feeling it was in the punchline. That’s amazing.

I was like, “Oh, no, I totally misunderstood this.”

But when you did get work, you got a lot of work. I guess being in the D.C. area was very beneficial to you because “The Wire” was set in Baltimore, which is basically a suburb of D.C. You got cast on one of the best TV shows of all time right out the gate. What was that experience like? Did you know it was going to be a thing or was it just a thing that you auditioned for?

No, I had no idea. Starting in the D.C. area was beneficial and great, partly because of “The Wire,” but largely because the theater community was very warm and welcoming and I knew nothing, so I would ask people questions all the time. They would give me answers and leads and give me suggestions of things to do, places I could submit myself for auditions, places I can go, take classes. All those things were super encouraging and that’s actually why I ended up continuing to pursue this.

I was an extra on “The Wire” actually. I was a background extra in the pilot episode and then I was an extra in a courtroom sitting next to Dominic West. I was wearing a police uniform. I did that a couple times as an extra and then later on they brought me in to audition for Marlo and I didn’t get that. Then they offered me Slim Charles and I said, “Yes.” I was super excited. At that point, I had already moved up to this area and in New York, New Jersey and I was taking classes. I realized that the day that I was going to shoot my first day of Slim Charles, I had a clown final, and so I called them.

A clown final.

I was very ignorant, and I had no guidance, and so I called them and told them I couldn’t do it. They said, “Why?” I said, “Because I have a clown final,” and they said, “You have a clown final?” I was like, “Yeah,” and so I didn’t know that’s not what you do. So I turned it down and then a couple weeks after that they called me back and said, “The creators have another role. They want to know if you’ll take this,” and it was Chris.

Oh God, you got so lucky, Jesus. For people who are reading — I know a lot of people who went to drama school — “clowning” is actually a class that you take. It’s like miming and improv, right? It’s body work.

It’s great for freeing up the body and the performances. Even if you don’t do a role that is clownish, it’s great for what it does for the artist.

So, you’re on “The Wire.” It completely blows up. Were you at any point concerned about being typecast or put into a box because the role is so powerful, you are terrifying. Your character was terrifying. Were you ever worried about that becoming a burden for getting work?

Initially after it blows up and I started getting offered these roles, either straight offers or asked to audition for these roles that were basically lesser versions of Chris as far as not written as well, just playing a thug and I didn’t want to do that, especially after having such amazing writing from “The Wire.” I remember during the fourth season, I believe, I shot my first movie, which was “The Savages.”

Philip Seymour Hoffman and Laura Linney. Incredible cast.

Yeah, Laura and Phil looked out for me on set, just really educating me as far as how things are supposed to go on a movie set. That told me that, “Okay, I can do roles that aren’t in this dark street space.” That’s what appealed to me, so I did get offered a lot of those initially, but then I was lucky to be able to book roles that showed other sides of me.

In the list of actors that you’ve worked with over time from like Jeff Daniels to Jeff Bridges, John Lithgow, Michael K. Williams, Idris Elba, Laura Linney, Philip Seymour Hoffman, it’s just a murderer’s row. How much more of a nuanced understanding of your craft do you have today compared to when you were on day three or four of playing Chris?

Oh my gosh, it’s night and day. I remember being on the show and I had no idea what I was doing. I would ask Ed Burns, “Am I doing it right?” He’s like, “You got hired to be what you’re already doing.” I’m like, “Okay.” But I would then go into the honeywagon after the scenes and just collapse from exhaustion. I was full of so much anxiety about what I was doing out there on set and I knew that it was only a matter of time before they realized they made a mistake and let me go. And Chris is a dark character. I was just starting, so I didn’t really realize or [had] no ways to leave that behind, so I would take Chris with me and that’s not a good thing.

You don’t want to do that.

No. No. No. I won’t do that. Then eventually, I learned ways to separate church and state, which helped me as an actor and it’s night and day.

Do you have a favorite? A collaborator or a favorite actor from when you were growing up? “That’s my person,” man, woman, whatever.

There’s so many and it’s hard to choose, but for the longest time I’ve just had such a huge artist crush on Daniel Day-Lewis.

He’s an alien. He’s unreal good. Good call. And that’s funny because, and I was going to get to this later, you wrote a piece for The Times and the title is “My Left Foot.” You’ve written a couple pieces for The Times. First of all, you’re a good writer. This has always been a thing that you’ve done?

I was double major in PoliSci-English and so we had to write a lot for those. I realized I’d much rather write a paper than take a test. But after college I didn’t really write. I wasn’t really required to work and so when I started acting and then opportunities came up, but the first article I wrote for The Times, it was just by chance I was going trekking the Himalayas with my agent at The time. [I had] a friend at The Times and I just let him know I was going to be gone for a while and then he hit me up before I left. He pitched the idea to the travel editor and it’s like, “Yeah, the travel editor said If you want to put something together from your trip when you go, they’d be happy to take a look at it.” I was like, “Okay.” That’s how it started.

It’s about a trek in Nepal that’s evocative and puts you in the place where you feel your pain literally and then your exaltation, but you conclude the piece in a way that I thought was interesting. You’re talking about how competition has always been the driving force for you, but you found something just as powerful in stillness and peace. When you think about competition, it’s always been a driving force for you? Who are you competing with? Are you competing with yourself? What is competition to you? Are you competing with other actors?

Earlier in my life, because wrestling had done so much for me, you’re competing against opponents and so on, and I could achieve a lot by setting a goal of like, “I want to beat this person or get with this person or surpass this person,” and it helped me achieve a lot. Even if I fell short, I still was highly productive. But as I mentioned in that piece, competition, although it can help you achieve a lot, it’s a really loud engine and it’s disturbing and it draws away from other resources and it doesn’t really let you rest or recuperate or grow. I realize I have to find a different engine, so now I don’t compete against anyone. If I compete, it’s against myself and even that is with the goal of understanding myself and where the growth opportunities are.

Has acting helped you understand yourself better or, I guess, other people? That’s one question. Another question is how do you define success as an actor? Has it helped you understand yourself?

It has. I always joke with folks that acting is cheaper than therapy ‘cause you get to work out all types of angst and mythologies and so on. But I also highly recommend therapy. You get to put yourself in the headspace of different characters, but then if you have really good writing, also, you get to live out this layered life. So, in all those things it’s an exercise of the spirit and the mind, so what’s left after you’ve been reduced, your mind has been reduced. You spare your body and you’ve done the show eight shows a week or you’re on set for 14 hours and you have to still deliver and then deal with the politics of being on set and still give to this character who you are. When it’s all said and done after all that, it’s really interesting to me to see, to look at that pile of whatever I’m left, what I am. It has helped.

One of your more recent “prestige” roles, or whatever you want to call it, was Tom Robinson in “To Kill a Mockingbird” on Broadway. You wrote about how deeply the role affected you. You wrote that “to play a part that makes me the daily object of racist invective and racial violence for a majority-white audience” was literally your day job for a while. Your character dies by violence every night. The N-word is used constantly. Did that role take a toll on you or were you able to separate church and state as you say?

I didn’t realize it was going to take a toll till the first day we did it in front of an audience. We had workshopped it for a year in the basement of Lincoln Center and that was an amazing experience to just be around a table with all these smart actors. Even [producer] Scott Rudin. Scott was there a lot. He contributed a lot as far as notes and so on. And so we just massaged it and worked and massage worked. Watching how Aaron [Sorkin] digested and then came up with new drafts. I love that process and so I forgot that this was ever going to be a play people saw, let alone be on Broadway. It was disconnected from me. And then previews start and it was a different thing like, “Oh, it’s right. This was always intended to be in front of an audience.” I realized that this was going to be tough. One thing that definitely helped was as a New Yorker, I spent most of my time in New York avoiding Times Square.

Yeah. Same.

Doing this play, I basically live there and then I’d ride my bike back to Brooklyn. That was my release. I got to work my body and my mind, listen to music, and then come back and eat my brownies and ice cream and it’s like, “Okay, that was my release. And I would just do it over and over.”

The play of course was on stage and running during the previous administration. There’s something about the timing of that that made the play all the more resonant. I wonder if you can talk at all about the climate outside the theater or what was going on politically versus what was going on on stage every night. It just feels like it had to have been, “Everywhere I turn …”

Absolutely. That that’s part of the reason I wrote it. The country was in so many ways toxic and that toxicity was fed from the White House. So, after doing this show where there are elements of it where this is how beautiful we can be, even though really ugly things happen in it, then I left the theater and there’s like, “Oh wow, I’m still a Black man in America,” and all kinds of things can happen and it’s increasing. Because it’s now okay to not only think these things, but to act on them.

I believe that people have the right to think whatever and believe whatever. People have the right to be racist. People have the right to be misogynistic. But obviously you cross into violating other people’s rights when you start to treat people that way and you start to act on those things. So what Trump did was encourage people to act on these beliefs. That was obviously highly dangerous, and so I felt that every time I left the theater, it was one of the things that went into why I needed to write this piece.

He said the quiet part out loud and then everyone felt empowered. How do you put the toothpaste back in the tube after that?

I don’t know if we should. It’s better to have it out there and let’s deal with the ugliness of ourselves. Let’s deal with it. How do we make better citizens if this is what some of our citizens, a lot of our citizens, are fostering? Okay, well, we can just be mad at them and draw our lines and not really try to understand them, or we can try to figure out, okay, how do we make better, more empathetic people?

How do you do that? Some of these people are so far gone or so entrenched in their beliefs. That’s a very compassionate stance that you have. How do you act on that?

This might be somewhat controversial. It’s acknowledging that they have the right to believe what they believe. If they have racist views and misogynistic views. It’s acknowledging: You can believe that, you have the right in this country to believe that, and I acknowledge that you have that right. “Okay, this person is still a human being.”

The other thing is, what’s our goal in communication? Is our goal in communication, especially as liberals, to convince and convert? Although it’s altruistic, and it’s a beautiful goal, it’s not necessarily without his own issues. I have to acknowledge a racist is a human being too and that they have the right to be racist and that I still have to afford them the cordiality of being a human being in the same space.

That’s tough because I don’t think necessarily people on the quote-unquote “other side” are going to adopt a similar stance. The trickier part for me is the biases that we all have ourselves that we can’t even see, which everyone’s got for something. What are the biases that I don’t see? What are the assumptions I make that I don’t realize are assumptions? And how do you unpack all of that and how do you communicate to other people when they have those types of biases?

You’re absolutely right and, hopefully, changing the environment will be more effective than trying to change the people. Like you said, “What are some of the biases I have that I don’t realize I have in addressing those things,” and if that’s the environment where more and more people are doing that, particularly in a healthy way, I think then we naturally get to a more communal way of acting, living with one another. Race and gender, those things truly disappear as opposed to what’s on social media as far as this virtue signaling.

So you’re in Bed-Stuy. Talk about a typical day in Brooklyn. Can you shout out some spots that you like?

I will shout out what I’ve been doing, and this has also been part of my routine and therapy, is like I go to a Blink gym nearby and just work out in the morning. It helps center me for the day and then I come back, and I just try to catch up with a whole bunch of things that I’m behind. I’m behind on all forms of communication. Depending on if I have to leave town soon or if I’m going to be around for a while, I’ll go shopping for food. Then, I’ll have some meetings in the neighborhood about, for example, Magnolia Earth Center or Restoration Plaza, just different things going on. I’m on the board of a MoCADA museum in Fort Greene. I’ve missed a lot of those meetings. I try to see while I’m here in Brooklyn, physically in Bed-Stuy, what I can do, what responsibilities and passions I can take care of while I’m physically here.

Is there anything you’re in now that you want to plug or anything that you want people to tune into?

I’m working with some really dope people to help a gentleman named Billie Allen who was arrested and convicted. He’s now spent decades in prison on conviction for a crime he did not commit and all his appeals are up and the last thing he can do now is petition for clemency, which is happening this month, so please pay attention to this. There’s a change.org petition out there. We are trying to get as much attention and eyes on this. This man has been away from his community and his family long enough, and so his name is Billie Allen in Missouri, and that’s a tough state to be sent away on, especially for a crime he did not commit.

Check out this episode of “Brooklyn Magazine: The Podcast” for more. Subscribe and listen wherever you get your podcasts.

You might also like