Swivel Gallery (Cary Whittier}

‘I’m casting a spell’: Artist Lamar Robillard wants his people to soar

Knowledge is power for this multidisciplinary artist whose “Dynamite in Da Ghetto” exhibit is on display now in Bed-Stuy

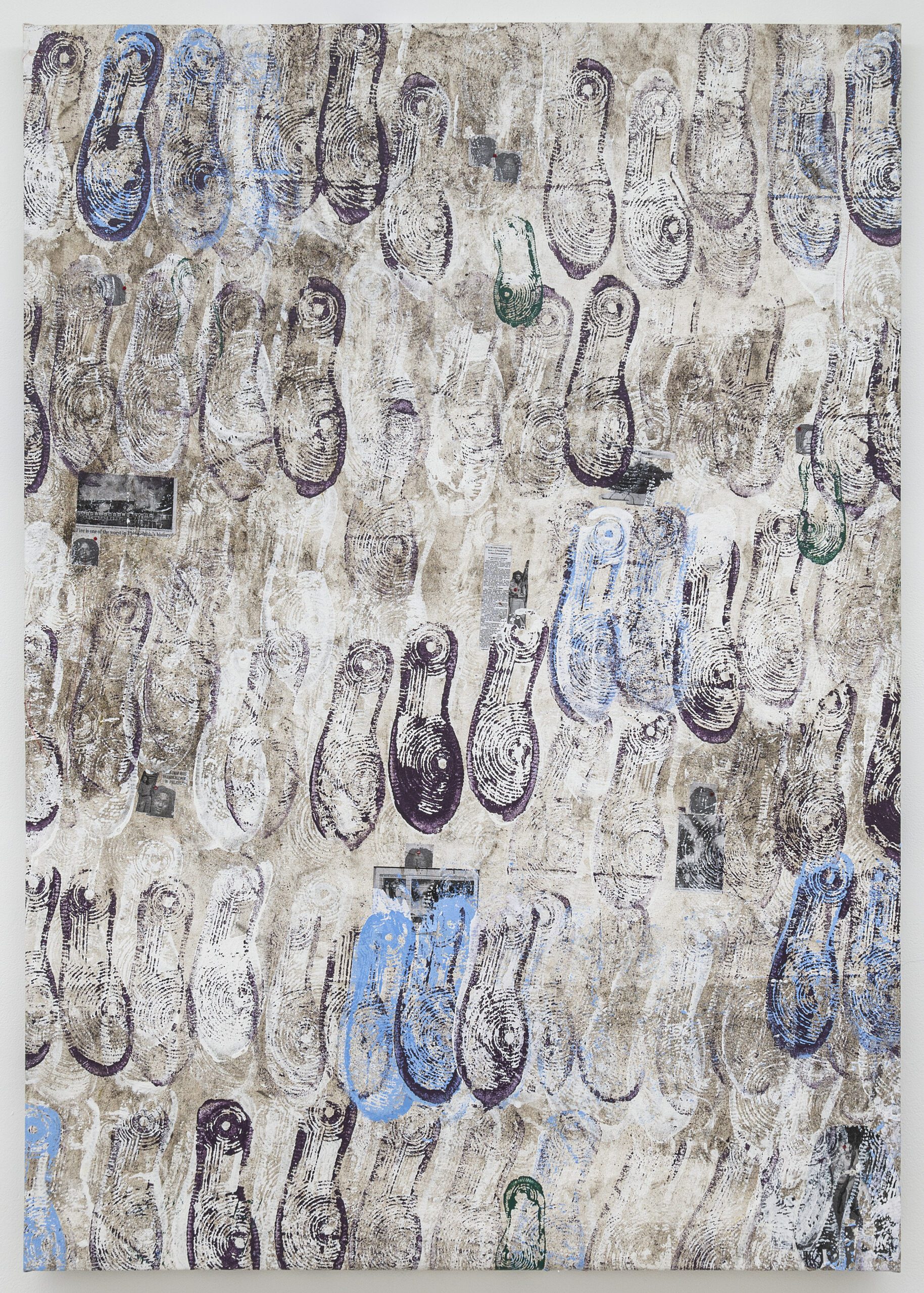

The soles of Lamar Robillard’s Nike Air Force 1s cover a six-foot-tall canvas, overlapping each other, agitated, rendered in different colors. There is undeniable movement here, filled with urgency. The work — done in dirt, paint, glass and thread — is titled “Placement Painting VI: Still Moving For Move, On the Move, What’s the Move?” and is one of 14 by Robillard currently on display at Swivel Gallery in Bed-Stuy in his exhibit “Dynamite in Da Ghetto.”

‘Still Moving For Move’ detail (Cary Whittier}

“Still Moving for Move” pays homage to the Philadelphia-based activist group MOVE, founded in the 1970s by John Africa. Rooted in the inherent value of all living things, the organization took on issues of animal cruelty, police brutality and the importance of individuality in the face of encroaching tech.

Like MOVE before him, Robillard’s ultimate medium is information. And though there is pain in these works, the information here never comes in the form of sensationalized trauma porn.

“My work is intentionally removing the trauma by having us engage with the system or be aware of the system from an inquisitive lens,” says Robillard. “For me, there’s so much more of the story to tell that we’re missing out on when we focus on the trauma; there’s so much beauty, and so much nuance. I wanted to put things in the space that made us happy, question the things we consume, engage with, and ultimately push people towards nuanced perspectives on what we’ve been conditioned to believe.”

Knowledge, as we know, is power. With “Dynamite in Da Ghetto” (on view until April 3) he uses as a launching pad the 1967 civil rights book “Black Power: The Politics of Liberation” by Kwame Ture and political scientist Charles V. Hamilton.

“Herein lies the match that will continue to ignite the dynamite in the ghettos: the ineptness of decision-makers, the anachronistic institutions, the inability to think boldly, and above all the unwillingness to innovate,” the authors wrote 56 years ago.

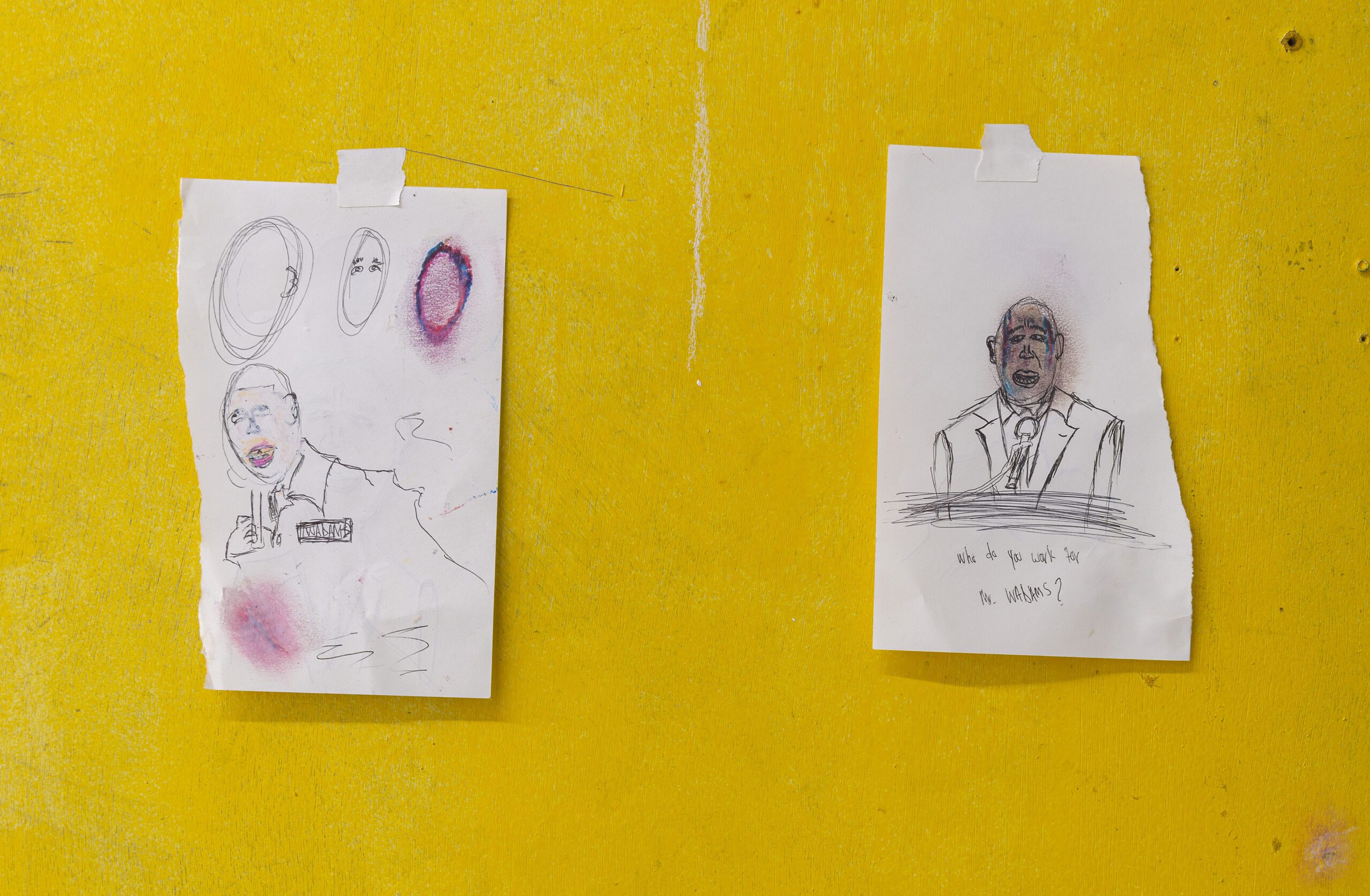

Banking off that today, Robillard explores five pillars of oppression that Black people experience under capitalism, specifically: miseducation, mass incarceration, gentrification, access to wealth, and police genocide. The piece “WADAMS,” for example, is a painted yellow door with drawings of a suited man tacked on, each depicting one of the pillars — and is a specific critique of Mayor Eric Adams.

‘WADAMS’ detail (Cary Whittier}

Untraditional

As a child, Robillard says his childhood friends and classmates told him that he had an artist living inside him. He always had a camera in hand and had many creative jobs, from styling gigs to curating shows. The moment it dawned on him that he was, in fact, an artist came with a book: 2017’s “Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power,” a survey of 20 years of Black American art and struggle.

“The book,” says Robillard, “just showed this vast body of Black artists especially works during the Black Power movement and Black Arts Movement, where there was a lot of found object and untraditional and unconventional art making, and I thought, ‘This is what I’ve been doing the whole time.’”

When you walk into Swivel Gallery’s squiggle-walled space, the first thing the visitor is confronted with is a new work called “Last Leg (of Cap) / Soul Food (Detail)” that unpacks the effects of white supremacy and capitalism’s downward stream of environmental racism. What is depicted as “soul food” here — a photograph of fried chicken and candied yams sticks out of a pile of sugar and salt on a wooden high chair — is a stark contrast, in presentation, to what the Black community is used to seeing on their tables. On our tables, “soul food” is about comfort and community; on Robillard’s table, it’s nutritionless and infantilized.

‘Last Leg (of Cap) / Soul Food (Detail)’ (Cary Whittier}

Robillard deftly uses surrealism here to conjure the effects of oppression while hinting at how close tantalizingly we are to freedom.

“Beyond being an artist, Robillard is a resistance worker with a deft understanding of the reparative power of art,” says Usen Esiet, curator of HAUSEN. “His work — rooted in community — is a reminder, as bell hooks states, that ‘we come from a long line of ancestors who knew how to heal the wounded Black psyche.’ Although Robillard is known for defying convention and his work thus rarely fits into any standard labels, there is no denying that he is part of a longstanding tradition of revolutionary Black artists.”

Robillard (courtesy Sidra Greene)

Ultimately Robillard, like his art, is hopeful. The multimedia film piece “Ghetto Bird In Us … Let The Sky Touch My Soul” and “Conversations on Flight” show everyday Black folks that can only be watched through a green construction board window in the wall. The takeaway: “I’m just wondering what it could look like if we [Black people] could fly away from the system and sometimes not even fly away from the system, fly with the absence of the system. More than fly away, soaring with the absence of restraint.”

These days, when he goes outside, he often looks up and admires the weightless freedom of birds, planes and helicopters. When there is nothing to weigh down your wings, you can go anywhere. Throughout “Dynamite” there are little Easter eggs on the wall, snippets of text that reference the Sam Greelee novel “The Spook Who Sat By The Door” and MoMA’s member: Pope. L, 1978-2001. One of the texts with the intention of “influencing good thoughts” reads, “Mothers Gliding” — replacing the term “Mothers Crying” — with hopes of reversing the pain felt from the constant fear of losing a child.

“As you exit above the doorway, it says ‘Fly Us All,’” Robillard points out. “I’m casting a spell on all of the people that are leaving the space to be free and to fly.”

You might also like