Waterfront Museum at sunset by PhotoJeff is licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0

Miller’s crossing: ‘The Hook’ makes its American debut

New Yorkers can finally see a long lost Arthur Miller work in the very place it was set: on the Red Hook Waterfront

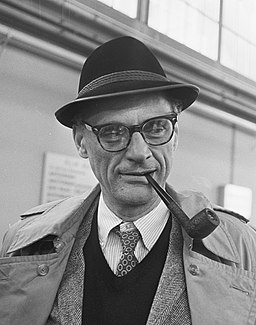

In the late 1940s, Arthur Miller lived on Grace Court in Brooklyn Heights, where he would write “Death of a Salesman.” One day in 1947, during a walk along the waterfront near the Brooklyn Bridge, he saw graffiti that read: “Dove Pete Panto,” or “Where is Pete Panto” in Italian.

Driven to solve the mystery, Miller began venturing further south, to Red Hook, which he would describe in his 1987 autobiography as a “sinister waterfront world of gangster-ridden unions, assassinations, beatings, bodies thrown into the lovely bay at night.” He hung out at bars frequented by longshoremen — including the landmark Sunny’s on Conover Street — and learned that Panto was a young dockworker who had spoken out against union corruption, only to pay a price. Eighteen months after disappearing, his body turned up in New Jersey.

Based on what he gleaned, Miller wrote “The Hook,” a screenplay set in Red Hook inspired by Panto’s story. But in the era of Joseph McCarthy and the House Un-American Activities Commission, the script was labeled overly communist and never made into a movie.

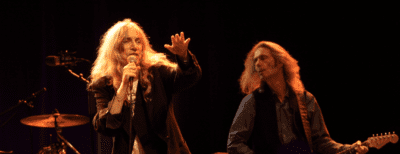

Over six decades later, in 2015, “The Hook” was adapted into a play and staged in Northampton, England. On Friday, the play makes its U.S. debut in a most appropriate setting: inside The Waterfront Museum, a preserved wooden barge that sits on the Hudson River in Red Hook. The show is presented by the Brave New World Repertory, known for its site-specific productions, and runs on weekends through June 25.

A goal will be to make the audience feel part of the sweaty, gritty world that the dock workers toiled in daily. Director Claire Beckman also hopes to “evoke a nightmarish, claustrophobic sense of entrapment and paranoia.”

“The [barge] is vast, I mean it’s got hatches, it’s got doors, it’s got skylights — and we’re using every inch of the space,” says Ron Hutchinson, a veteran Hollywood screenwriter who adapted the script in 2015 and has tweaked it for the barge production. “It’s moored on the water and every so often it gives a lurch and turns sideways, up and down, back to front.”

From a 2019 staged reading of the play on the Waterfront Museum barge (Jody Christopherson)

Pitching ‘The Hook’

In 1951, Miller and Elia Kazan drove to Los Angeles to pitch “The Hook” to an executive named Harry Cohn. (They were accompanied by a young Marilyn Monroe, who at the time was having an affair with Kazan but would later marry Miller.) When Cohn demanded big changes to the plot — notably that the union villains be clearly “communists,” Miller wrote in his autobiography “Timebends” — Miller shelved the script. A few years later he would publish the play “A View From the Bridge,” set in the same milieu but more focused on a love affair, and “The Hook” disappeared into obscurity.

Patrick Connellan, a British stage designer, years after working with Miller in the 1990s, retrieved a copy of the script from a research center at the University of Texas, inspired by what he read in “Timebends.” Connellan took it to another colleague, the stage director James Dacre, who in turn commissioned Hutchinson to work on the adaptation, with the blessing of the Miller estate. The final product ran for a few weeks in June 2015 at the Royal & Derngate theater complex in Northampton, about 70 miles north of London, and earned mixed reviews.

Not long after, Connellan was visiting his son who lived in Brooklyn when he decided to walk through Red Hook. He happened upon The Waterfront Museum and, stunned, introduced himself to its director, David Sharps.

“[Connellan] was gobsmacked when he went inside, because he realized, this is it, you know? Pete Panto would have worked on a boat like this,” Hutchinson says.

When Connellan pitched Sharps the idea of staging “The Hook” on the barge, Sharps thought he was talking about “A View From the Bridge,” which Beckman had wanted to stage in the museum nearly a decade earlier. Sharps called Beckman, a friend, asking if she had heard of “The Hook,” and she was immediately interested, having also read about it in Miller’s autobiography.

In 2018, Beckman organized a reading of the British play version on the barge with a group of actor friends, having lured them with free pizza and beer. Some read two or three parts.

“It was quite emotional for everyone, that it was the first time it was being read on American water — not even soil,” Beckman said.

Hutchinson insists the adaptation includes “all of Miller’s language” fit into “the shoebox of a state stage play with a very controlled number of actors.” He says it includes all of the sprawling action from a movie script, even a violent death — which in this production involves the dropping of a very heavy weight down a hatch, and a subsequent scream.

Beckman noted that they are even staging, with only a few actors, a “shape up,” the process that involved dozens of dock workers lining up each morning to get chosen one by one by employers (not unlike scenes in Kazan’s “On the Waterfront”). Historical black and white images will be projected as additional setting, too.

The museum was formerly a Lehigh Valley Railroad barge, believed to have been built in 1914 and also likely the last remaining all-wooden Hudson River barge left in New York. Sharps, a former juggler on cruise ships, found it in New Jersey and restored it in the 1980s, and it has been a museum open to the public docked in Red Hook since 1994.

Beckman says that Miller’s story is surprisingly relevant today, as New Jersey Gov. Phil Murphy has fought successfully for the right to pull out of the Waterfront Commission of New York Harbor — a body created in the 1950s to combat the mob corruption on the docks that Pete Panto fought against. Recent reports have shown that mob families continue to wield influence in the harbor.

Beckman called the move, if Murphy decides to withdraw, a “terrible idea.”

“And our governor is none too pleased,” she says, referencing Kathy Hochul.

But the play is also “about more than corruption on the docks,” Beckman says. “Miller wrote about human beings, and as the director, it’s the human story I’m interested in telling.”

“The Hook” runs June 9-25 at The Waterfront Museum at 290 Conover St., with performances only on weekend nights at 8 p.m.

You might also like