MC Lyte (Courtesy of Netflix)

‘The only girl here’: MC Lyte on 50 years of hip-hop

Pioneering rapper MC Lyte on her early influences, the globalization of hip hop and the new wave of female emcees

The word trailblazer gets tossed around a lot. But there aren’t many emcees in the 50 years of hip-hop that have had the track record, enduring legacy and influence of MC Lyte.

The Flatbush emcee broke down barriers in the late 1980s with conscious rap that drew attention to issues that affected the Black community, like addiction, racism and misogyny. With the release of her 1988 debut album “Lyte as a Rock,” MC Lyte made history as the first female solo rapper to release a studio album. In 1993, she was the first female solo rapper to be nominated for a Grammy, for Best Rap Single for “Ruffneck” — the first gold single by a female rapper.

Before she was even 45, she received the “I Am Hip Hop” lifetime achievement award from BET, in 2013. Among those who have cited her as an influence are Lil’ Kim, Da Brat, Missy Elliott, Lauryn Hill, Monie Love, Eve and others.

Now, MC Lyte will feature in “Ladies First: a Story of Women in Hip-Hop,” a Netflix documentary on which the Brooklyn rapper is also an executive producer. The four-part documentary explores the often overlooked role that women have played in hip-hop over its 50-year history and contextualizes the genre within the social, racial and political landscapes of the time through a female lens.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QMcnPdp54aE

Brooklyn Magazine sat down with MC Lyte (born Lana Michelle Moorer) to talk about the role of women in hip-hop, poetry and the ruthless nature of the music industry.

This interview has been lightly edited for concision and clarity.

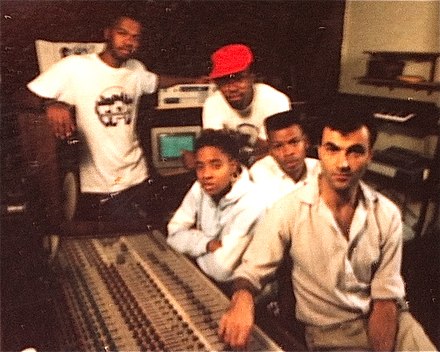

MC Lyte in 1988 at Firehouse Studios (CC BY-SA 3.0)

In the documentary, you talked about growing up in a “socially conscious” space in Brooklyn. How did that influence your music?

I attended a school that was really conscious in terms of history, and instead of gym we did jujitsu and martial arts, and instead of eating junk food we had the proper meals for lunch and we learned poetry and songs. It was a pretty cool space to grow up in and just get a taste of education from another aspect.

It made me aware of the drugs that existed in our neighborhoods. In Brooklyn it might have been crack, and in Harlem it was heroin — it was something everywhere in the ‘80s. It just made me want to reach out to my generation and try to tell them what bad news can come if you indulge in such activity.

I remember hearing a quote of yours that stuck with me, “If there’s a house burning down, don’t get mad at us for yelling fire.” Was it the storytelling aspect that drew you to hip-hop?

Yeah, absolutely. I remember hearing Melle Mel’s “The Message,” and that was far more impactful than anything during that time. I was very much into the disco movement as a kid, listening to what everyone else was playing, and then along comes this song that vividly paints the picture of what the Bronx looks like. Up until that point, I had never been to the Bronx, even though I lived so close in Brooklyn.

He painted this picture and I was able to see it in my head, and then there was the video and I was like, “Oh my God, there’s a place that looks like this that’s not too far away.” It was mind-blowing, and hearing the way he told the story made me want to tap into the creativity to paint a picture.

A common theme in the documentary was that a lot of the MCs started with poetry. Was this the same with you?

Absolutely! I think poetry is the truest form of rap and the art of hip-hop. Babyface once said that a great record reads as a story with one element of surprise. This stands true for Hip-Hop as some of the greater songs in the beginning were stories and even if you took away the music you’d still be interested to listen.

I remember doing a song called “Cold Rock a Party,” I wrote my rhymes and Puffy [Diddy] said, “Wait, you’re making too much sense?” One line doesn’t have to correlate with the next, and it can be a bunch of sporadic thoughts. Once I got the gist of it and I wrote it, it turned out to be one of the best sellers of my career. Poetry has so much emotion and feeling, and there’s no real expectation beyond it being interesting. It’s not judged in the same way that a song is.

When did you first realize that hip-hop had become a global phenomenon?

I think I realized it right on the precipice of “Lyte as a Rock” [1988] because I was sent to Denmark to perform with Audio Two and Da Youngstas as part of an initiative from Atlantic Records. Very early on I understood that hip-hop had no color lines, we were in the heart of Denmark with an all-European audience and they were loving the music, even if they couldn’t understand what we were saying. They loved the movement and they felt the emotion.

What was it like going from this young woman who barely left Brooklyn to traveling the world?

My mom says that she often prayed for me as a baby that I’d get to see the world. Now that I’ve seen the world it feels like a blessing, but it also seems unfair because so many people don’t get to do that. So I do understand I am holding a special space, and I’m extremely grateful.

What was it like to be the only woman on tour. Was it isolating?

Being the only one out there actually felt liberating. I was doing what I needed to do. I don’t know that I spent that much attention saying, “I’m the only girl here.” I just was. I had a manager and a crew who facilitated safety for me and I’d perform and go right back to the tour bus or perform and go right back to the hotel room. There wasn’t much room for me to get lost. I appreciate them to this day for taking care of me and babysitting a grown woman.

Another interesting aspect of the documentary was a focus on how artists are exploited in the music business. Talk about your experience with “Poor Georgie.”

With “Poor Georgie” we did what everyone was doing which was sampling before clearance. It just so happens “Poor Georgie” came out in 1991, and that was just about the time everyone realized and was like, “We’re gonna go after this hip-hop, they can’t just use our music!” Before, it was so under the radar and nobody even cared, but once they saw what it was capable of selling and the attention that it was garnering, it was time to garnish pay.

We used three samples in that song [“Georgy Porgy” by Toto, “I Wanna Be Where You Are” by Michael Jackson” and “My World is Empty Without You” by the Supremes]. And by the time we had finished, they took all the publishing. The song was already out so it wasn’t even like we had a choice whether to not do it and do something original so we could keep all of what’s made. Michael Jackson and Diana Ross both took half combined and then Toto took the rest, and that’s what you call getting eaten alive.

We have seen the SAG-AFTRA strikes in Hollywood. Do you think we will see something similar with music in the near future?

I hope so. All it takes is organizing and really saying it’s time, everybody else is getting paid. You have several artists that are probably getting what they think they deserve, but it’s not until you see the whole pie that you realize your slice is nothing. Maybe raising consciousness to the degree that we want to do it for ourselves or we get people to play fairly.

The doc ends with a focus on the new wave of female rappers like Latto, Saweetie and Coi Leray. Is this one of the most exciting periods for the genre with so much talent coming through?

I do think it is one of the most exciting times. We also had one of the most exciting times back in the early ‘90s with Ms. Melodie, Nefertiti, DJ Jazzy Joyce, MC Trouble and so many more. Every record label felt like they had to represent and have a woman on their label and especially Queen Latifah with Tommy Boy.

That was a great time and I believe this time is great because it took so long for us to get here. We are now in this space where there are so many that are continuing to do what it is that they love, whether they are on the front of the magazine or not, whether they are on the top of the chart or not. There are so many ways that you can be successful that are void of validation from the “big corporations” that make this thing work.

You might also like