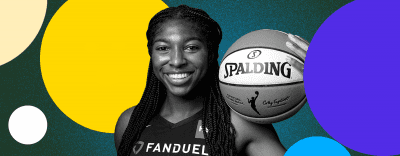

Photo by Bryan William Jones, photo illustration by Johansen Peralta

From Brooklyn to Astoria (Oregon): What it’s like to bike 4K miles across the country

Journalist Clive Thompson cycled 4,150 miles from coast to coast as reporting for his next book on 'micromobility'

Like what you’re hearing? Subscribe to us at iTunes, check us out on Spotify and hear us on Google, Amazon, Stitcher and TuneIn. This is our RSS feed. Tell a friend!

What’s the longest bike ride you’ve ever taken? Clive Thompson probably has you beat. In April, the journalist and author set out to bicycle across the entire country — coast-to-coast, 4,150 miles total — as part of the reporting for his next book.

He documented his trip in real time — 70 days, 10 weeks on the road, broken up by a brief return trip home — on Strava, the social app that tracks your bike rides, runs and hikes. Thompson is a lively and entertaining writer, a journalist who covers technology and science for the New York Times, Wired, the Smithsonian and on his own Medium page. He is the author of two books: “Smarter Than You Think: How Technology is Changing Our Minds for the Better” and “Coders: The Making of a New Tribe and the Remaking of the World.”

And this week Thompson, a Brooklynite born in Toronto, is our guest on “Brooklyn Magazine: The Podcast.”

Thompson is working on a new book about “micromobility,” a clunky term for moving things and people around in vehicles that are smaller than a car. Hence his epic cross-country ride: He wanted to see how micromobility plays out — or doesn’t — in various parts of the country, all while micro-mobilizing himself.

The book won’t be out for at least a year, but we wanted to hear from Thompson, while the ride was still fresh in his mind, to talk about what riding 4000 miles does to someone, physically, mentally, emotionally.

“I definitely finally got what all the hardcore athletes — the real athletes, not just the howling jocks — what they believe and understand about the power of pushing yourself physically,” he says. “There’s something really exciting about that.”

The following is a transcript of our conversation, which airs as an episode of “Brooklyn Magazine: The Podcast,” edited for clarity and, to a lesser extent, concision. Listen in the player above or wherever you get your podcasts.

You rode 4,150 miles in total across the country on a bicycle. This is part of a book you are researching on micromobility. What are we talking about when we’re talking about micromobility?

It’s a buzzword. I don’t really like it. I’m actually looking for a better one. So any suggestions you have or anyone listening to this, please contact me. But basically, the phrase emerged five or six years ago. Some thinker was trying to characterize all the forms of transportation that were merging that are basically kind of smaller than a car. So that could be a regular bicycle, could be an electric bicycle, could be someone on a regular scooter or an electric scooter.

A Revel.

A Revel, exactly. It could be someone using one of these teeny little cars. Something that I’ve been seeing more and more of, and I’ve encountered in my ride, golf carts. Man, they’re all over the country. So basically, it’s micromobility, I’m really interested in the rise of that and what role it might play in decarbonizing some of our transportation, clawing some of our everyday movement of people and things back from personally owned cars basically.

And that’s what this book is going to be about, the rise of this trend and its environmental impact, technological—

Absolutely. Energy impact, technological impact, cultural impact. It’s also about my ride, because I wanted to see the way the whole country moves around. I was really interested in getting a vivid sense of everything from downtown cores to middle-of-nowhere areas to sprawling suburbs, how do people get from point A to point B?

Well, of course, you could do that without actually bicycling across the entire country. So this book isn’t solely a chronicle of your bike ride. It feels like an enormous undertaking for something that’s maybe not the main purpose of your book. What was the thinking here?

I’m just in the beginning of researching it. It’ll change and evolve as it goes on, but the thinking was there’s also memoir aspects of this. I’m interested in writing about my relationship with becoming athletic in the middle of my life too. When you first met me, I was in my early 40s and I had spent decades not really being very athletic at all in any way. I was always a healthy person generally. And you live in New York City, you move around a lot. You have to walk a lot. You have to go up and down stairs. I was not a sporty person at all. I was quite alienated from sports.

Same. You’re a poet.

I’m a poet, but, no, I studied English and political science, super nerd stuff. I was like a computer programmer nerd in the ’80s, like OG monitor tan stuff. One of my father’s friends lent me a VIC-20 for a summer, and I basically spent from 8:00 a.m. to midnight programming for four months. Didn’t go outside the entire summer.

What is a VIC-20?

The VIC-20 was a cheaper version of the Commodore 64. My mother would not let me buy — she would literally not let me, with my own money — buy a computer, because she worried that I would, almost a direct quote from her, “only play video games all day long and drop out of school.” And so the only time I got to have a computer was when my father’s friend bought one, realized it didn’t do anything unless he programmed it, brought it over and gave it to me for the summer. And I just programmed in a haze basically for the summer. That was the profile, the extremely unathletic profile, of my youth that maintained pretty much through my entire life.

You’ve written recently about your interest in the past couple of years in an idea called “rewilding” your attention. I would imagine there was some connection to that in riding a bike 4,000s of miles. What is rewilding?

So rewilding your attention is a very cool phrase that I stumbled upon two years ago. I was just dorking around on some personal blogs, and I saw someone wrote a post relinked to the tweetstorm of a digital consultant and blogger named Tom Critchlow. And he was talking about how when people are sort of trying to amass an audience online, they very often sort of pay attention to all the viral things that are blowing up on social media. They try and pounce on those and write about those so that they can hopefully garner some of the eyeballs that are swirling around this, whatever the viral subject of the day is.

That’s a classic journalism ploy of the past decade-plus: something’s trending, jump on it, get those eyeballs.

Jump on it, get those eyeballs, exactly. And so he was saying, the problem is you wind up thinking about the same stuff everyone else is thinking about all the time, and it’s deadening. Then he said, in this wonderful turn of phrase he goes, “You actually can rewild your attention and you can actively spend more time looking at weird idiosyncratic stuff that’s being written for smaller niche audiences.” And, A, that was something that I’d been trying low-key to do myself. I had spent the early days of social media staring at all the viral trends that were being pushed by the algorithms and refreshing over and over again, and I had felt that same sort of deadening sense of my brain’s becoming very undiverse. And I love the rewilding metaphor because I’m a science journalist. It’s become a big thing in people thinking about the health of the natural world, right? It’s actually really bad whenever you get an environment that is dominated by one species, one plant, one animal.

One meme.

One meme, one information source, one thing. And so much as it’s healthier for the landscape to have a diversity of stuff going on, it’s healthier for our brains to have a diversity of stuff going on. So I’ve been, sort of over the last two years, writing a lot of posts and thinking about how you do that, how you sort of decouple your brain from the stuff. Not a permanent decoupling. I do want to know what the big debates of the day are. I just maybe want to put a cap on how often I swirl around that drain.

I was familiar with your work before I knew you. You were always good at finding the nooks and crannies of either culture or tech or science. So I would imagine a ride of this magnitude goes some distance toward rewilding your attention just by virtue of being offline for so many hours a day.

It’s actually kind of funny. So one of the things people would ask me when they heard I was cycling across the country was, “OK, so what podcasts are you listening to?” And I told them, “Well, actually I’m not listening to anything.”

Amazing.

For a couple of reasons. One is that this is just a safety issue. Some cyclists do like to listen to stuff, and they maybe wear headphones that ambiently mix in some of the road with the podcast or the music so you can hear an approaching truck. I feel very much like if I’m on a road and there’s 16-wheelers flying by me six inches away, I want to be totally alert and totally paying attention, so I don’t wear headphones. And what that means is, like you said, that’s 10 weeks of cycling six to eight [hours] a day. You’re not engaging with any media at all, nothing going in your eyes, nothing going in your ears.

So there was something, and actually I’m sort of working on an essay now that is about that, I’m going to put up on Medium called “10 Weeks of Silence,” where it’s sort of meditating on what happened to the way I think, or the things I think about, or the tide pools and currents of my mind. When I say offline, I mean offline from the internet, but offline from a paper book too. You can’t look at that either while you’re cycling. It’s just you and your thoughts. It was really interesting, really mentally interesting, and I think you’re exactly right, it dovetails neatly with my thinking about rewilding your brain, because it did some fun things to my attention.

I have so many questions about this ride. It’s just fascinating. What is a typical day like? You’re literally riding anywhere from 50 to 60 miles a day, up to 100 miles a day in some cases. I tracked you on Strava. What’s the mix of riding, working, resting, reporting? You’re somewhere in Idaho …

The way it worked is, my goal was not to destroy my body. I’ve gone on rides where I do like 100+ miles a day. And after four or five days, for someone who’s in his 50s as I am, your body’s starting to break down. So I was like, “No, this is a marathon, not a sprint, so my goal is going to be on the average 65 to maybe 70 miles a day.”

That’s a huge number though. I went on a ride a week ago, it was 30 miles through the borough and Queens, and I don’t know if I had another 40 miles in me.

It is a little nuts to say, “I only did 65 miles a day,” but I’d done enough long-distance cycling to know that I could probably do that OK. But you also have to, and I did, build in break days. In the parlance of cycling, everyone calls them “zero days,” zero miles. And so about once on average I guess, once every seven to eight days, I had a zero day. But on the days that I’m riding, I guess on average you go maybe anywhere between, if it’s hilly, when you’re going up and down a lot of hills, like maybe nine miles an hour to, if it’s really flat, 14 miles an hour on average over the whole day. The riding could be anywhere from five to eight or nine hours. I would try and start early, because I was doing this in the spring and summer. It gets pretty hot, particularly by the time I got out West. We got one of those heat domes. It was like 100 degrees by 4 in the afternoon.

I would try and start really early so I could be basically done by just after lunchtime, 12 or 1. That meant I could chill out in wherever I was and do some of that reporting, where I’d be like, “All right, let me go see who’s around this area, who’s in this town, let me go talk to them.” Or it would leave me time, if in the middle of the ride I ran into someone interesting, I would chat with them and take some notes and whatnot. But things change depending on what the road throws at you. This is my plan, but I was thrown for all sorts of loops at different points and times.

We make plans and God laughs, which does get into one of my questions. How do you plan for something like this? It’s both about the right gear, the right amount of gear, but you’re also meeting up with people to interview, you’re scheduling things in advance, lodging. There’ve got to be so many variables once you hit the road from weather to gear malfunctions.

If anyone ever wanted to do this — and I would encourage people, it’s fun, maybe don’t cross the country, but I don’t know, do like a four- or five-day trip. That’s totally doable. The first part was trying to figure out my route. How do you get from Brooklyn to the Pacific Coast? Now, fortunately I didn’t have to invent this from scratch because there’s an organization called the Adventure Cycling Association. It was founded by a couple of young ardent cyclists back in the early ’70s, who I actually met. They’re now in their 70s.

They put out all these maps of different routes you can take. I sort of looked at it and stitched together a ride across the country. The most common route, if you wanted to like, “OK, I want to cross the country,” they have something called the Trends America Trail, and it goes from Norfolk, Virginia, all the way up to Astoria, Oregon. It’s the most popular route. If you wanted to cycle and know that you’re going to run into a lot of other cyclists doing this, that’s the one you’d take.

I didn’t want to do that because, for the purpose of my research, I wanted to hit not just sparse rural areas, I wanted to hit a couple of major cities so I could see what mobility looks like in big cities. The route that they planned intentionally avoids big cities, because they think it’s more pleasant, and they’re probably right, to go through fewer big cities. So I stitched together a ride that kind of went from Brooklyn down to Philadelphia, and then across the south rim of Pennsylvania until I got to Pittsburgh, which was my next big city, then out into Ohio, down and across to Columbus, which was the next major city, out to Indiana and to Indianapolis, which was great, then cross Illinois, and then into Missouri, where I hit St. Louis, then up a little north to the northeast corner of Kansas, Kansas City, and then I bombed across the Great Plains, across Kansas and Nebraska. There were no major cities for 700 miles, man.

That’s a long time.

And then I got to Fort Collins.

And then you hit the Rockies.

Then I hit the Rockies, yeah, and there’s not a lot of big cities. There’s a couple. There was Missoula, Montana, there was Baker City, and then there was Eugene, Oregon, and then there was the water and I was across the country. So those are all routes that have been created by the ACA. And they have great maps. I would say to anyone, if you’re thinking of doing any type of little ride, just go to the ACA, find a route that you want to do, maybe it’s near you. The information they offer is fantastic. So that was the first step of the planning.

What’s your bike? What are you riding?

I was riding a Kona Sutra. So the company is called Kona, a Californian firm, and it’s a model called the Sutra. And it’s kind of interesting, some fun local knowledge here. So I’ve been going for years to 718 Cyclery.

Wonderful shop. I’m going to shout out Joe at 718. He does these micro tours upstate. You go camping three days. I’m terrified to do it, much less ride across the country, which suggests to me I should do it, but shout out to 718.

Absolutely. And if you do, let me know, I’ll do it with you, because that would be so much fun.

Let’s do it.

I went to Joe and I said, “I’m going to cross the country for a book and I need some advice on what the perfect bike for me would be.” And so we talked about it for a while, and he basically said, “The truth is you could build a bike from scratch, but everything you’ve told me suggests that I think you should just ride a Kona Sutra.” And he was like the third person who had told me that, but his opinion carried the greatest weight because he really knows his apples.

And so the thing about a Kona Sutra is that it’s a little bit of a turducken of a bike. It has thick tires, but not as thick as a off-road bike, but thicker than a hybrid. It’s got a steel frame, which is important because I’ve had real problems. We can talk about this more in a little bit. I’ve had real problems with vibrations causing numbness in my hands, and I did not want that to be a showstopper for this ride.

Same, yep.

I didn’t want to develop such numbness that I had to call my publisher and go, “Sorry, can’t ride across the country.” So steel is very good at absorbing vibrations. It’s like a Meccano set. It’s got lots of little points where you can attach stuff. It’s very adaptable. It’s rugged and sturdy as hell. It’s got drop bars, so you can ride in a aerodynamic mode or you can sit up more upright, and it comes with a leather Brooks saddle, which takes — and we can have some fun talking about this — takes some time to break in, as I discovered.

All in all, it’s really a phenomenal bike. I had a blast riding it. I would recommend anyone, if you’re thinking of doing some big, long rides, take a look at it. It is pricey, but it’s not as bonkers pricey.

I was going to ask.

Yeah, it was like about $2,300.

That’s pricey.

That’s pricey, but I met people who were riding like $5,000 bikes and up. You can blow a lot of money. So that’s what I rode.

I’m assuming you were an experienced camper before. Aren’t you a Boy Scout? Camping and I do not get along. You knew what you were doing already.

Yes and no. When I was a kid, we camped in the Boy Scouts, yeah, for 10 years, and we did winter camping too…

Ugh, no thanks.

… With hilariously inadequate equipment, like thin little tents in the middle of the winter. It was practically child abuse. But I hadn’t camped a whole lot in my 20s, 30s and 40s. I wasn’t worried about doing it, because I’ve done a lot of it, but I had to get new gear. I had to get gear that’s really, really light. Because when you’re putting together a long bike trip, it’s kind of like being in the military.

You have to think long and hard about everything that’s going to go on there, because you are going to carry that up the Rockies and up the Appalachian Mountains. So again, with Joe’s advice, he hooked me up with a really fantastic tent, the Big Agnes Copper Spur and, very light, but roomy, it fits like 1.5 people. I didn’t feel cramped in it, and it folded up into something just like the tiny little package. The camping was actually honestly really a fun part of the trip. I did more of it out West than I did out East because, when I started, it was in late April, early May, and a lot of campgrounds weren’t even open yet.

You talk about, at least in your Strava update, something that was interesting, because you aren’t camping every night. There’s this network of sort of Airbnbs for cyclists called Warmshowers, which is kind of a gross name.

It’s a terrible name. They really need to rebrand that thing, yeah.

Talk about Warmshowers. You’re staying at hosts’ houses who are like, “Yeah, cyclists along the route, come crash here.” You didn’t meet any serial killers, I’m assuming.

No, and nor did they. When you think about it, it’s kind of a risk on both fronts. What Warmshowers is, it was founded many years ago, and it’s basically a social network where, if you’re a cyclist, you say, “Okay, here’s where I live. If anyone’s coming through town, you can crash with me.” Vice versa, if you’re on the road, you can look at a map and you can figure out, “OK, I’m going through this town.” There’s five or six hosts. You ping them, and if they’re free, they take you.

I, over the whole trip, found this incredibly useful. I think if you were to do a pie chart of all the data that’s on the road, I used Warmshowers probably a little under a third of the time, somewhere around 25 percent maybe. I camped about maybe 30 percent to 40 percent of the time. And the rest, like the other 30 percent, was like Motel 8s, mostly when I was crossing the Great Plains and stuff, because there were just no camping, and it was tornado season, so I wanted to be indoors.

So Warmshowers, really cool. Man, I met such wonderful people. I met a lot of retirees who did a lot of stuff, but a lot of young people, people who worked in government in their towns, a former firefighter out West who used to go around putting out fires in the Southwest and Northwest, just really interesting folks.

You set out on April 26th of this year, and I love this, two miles from your house, your bike breaks down, two miles in.

Two miles in. It was brutal.

Did you ever just completely lose it? I mean, you’re dealing with mudslides. I’ve known you for a while. You’re very upbeat, you’re very engaged, you have a lot of energy. I think I’ve seen you lose it once. But you’re dealing with mudslides at the Cumberland tunnel. You had to climb. Your left crank broke outside of Columbus. Did you ever just throw your bike on the ground, like McEnroe style, and just say, “I’m out. Fuck this, I can’t do it”?

The mudslide was not fun. The crank breaking, all those things are unpleasant. The heat dome was unpleasant. The trucks were unpleasant. The only moment that really gave me pause was my really terrifying day of multiple dog attacks in Illinois.

Yeah, I was going to ask about those.

That was a moment when I was texting my wife and going, “I did not sign up for this.” I signed up for all manner of physical misery. I knew that. But I did not sign up for naked terror of unchained dogs attacking me. I wrote this little essay, “Dogs Vs. Highways,” for Medium, where I was basically saying, “People think highways are scary.” And I did think highways are scary. I’ve always been a little nervous riding on them. You got these big trucks, all you need is one guy on an SUV to be looking at TikTok when he gets near you and you’re pancaked. And so I loved the idea of, whenever I could, riding on these nice, little country roads, because it’s beautiful and everything smells wonderful and there’s these cute little farmhouses and whatnot.

But in Illinois, for whatever reasons, there’s two problems. A friend of mine who lives in Illinois explained to me, “Most farmers just don’t chain their dogs up because they’re using them for security,” understandably. But the farmhouses in a lot of these areas are right up against the road. In Kansas and Nebraska, they’re like half a mile setback from the road, but they’re all right up against the road. So what that means is you’re riding along, and the dog’s chilling on the front porch, and it sees you, and it just comes right at you. It happened three times in, honestly, like an hour and a half, two hours in one day.

Jesus.

That was the moment when I was like, “I got to figure out how to deal with this.” I don’t know if I’d call this a showstopper, but it legitimately shook me a way that nothing else, no hill, no lightning storm had shook me before.

Wow. I’m guessing no dog ever caught up with you.

None that bit me, although I hung out with people who did get bit. One guy I rode with, Logan, I rode with him in the Rockies for about maybe 10 days. Logan went ahead, but I would keep up with him and text him and, “How’s it going?” And when he hit Baker City, he was like, “Things were great until I left Baker City and a dog chased me and got its jaw around my ankle.” Fortunately, a car came along, headed towards the dog on that side of the road, and scared the dog and it let go, and he managed to get away.

Oh, my God.

But to give you a sense of how bad this can be, when I was in Columbus, I hung out with a bicycle collective, one of these nonprofit collectives, where they fix up bikes and they teach people how to fix bikes and they sell bikes or give them away to low-income folks as mobility. It’s really cool. I discovered these all over the country, incredibly cool things. One of them had a woman, who was an early founder, and she was like a tournament-winning rock climber and a long-distance cyclist, and she was attacked by a group of pit bulls and lost a leg.

Oh, my God!

It’s horrifying. It’s a horrifying story. So nothing remotely as bad as that happened to anyone I met on this trip, but definitely, yeah, the dog attacks are significant. If you get a bunch of cyclists together, long-distance cyclists, like I was in Kansas City on. I went to a guy’s house and he had a fire pit and there were several long-distance cyclists all hanging out, and for an hour we just traded dog stories. It’s one of the things you talk about.

I did want to ask you, you ran into a lot of cyclists doing insanely long rides.

Oh my goodness, yeah.

How common is this phenomenon? Were you surprised to keep running into people, seeing the same people on the trail?

Well, one thing that I was trying to find out, and I’m still trying to ascertain this, I’ve come to realize I don’t think I’m going to get a strong number on this. The question is, how many people cross the U.S. on a bicycle every year? When I went to the offices of the ACA, the Adventure Cycling Association, I asked them. And they said, “Well, we get about 500 to 800 visitors a year.” Because their office is in Missoula and Missoula is on the TransAmerica Trail, it’s well known that if you’re crossing the country, you stop at the ACA. So they probably get the majority of people who are crossing the country on the TransAmerica Trail. They probably get a good sample of them. So let’s say, OK, 800 to 1,000 people do the TransAmerica Trail a year. How many people cross the country using some other route? I mean, at that point in time, no one really knows. Maybe another 1,000? My best estimate is between 1,000 and 2,000 people a year.

That’s a lot of people.

It’s a lot of people. It’s way more than I would’ve thought. I met a lot of folks. I met people who were doing really slow, casual rides, like 50 miles a day. I met one woman from the U.K. who was doing like 130, 140 miles a day average. She was just a monster. She would just vanish into the distance like the Millennium Falcon when you tried riding next to her.

Your stats are no slouch either. Day 20 is 95 miles, day 21 is 106, then you have a zero day, then 92 miles. It’s crazy.

That’s me approaching the Great Plains. The thing about the Great Plains is people do this at different times of the year, mostly in the summer. I, for various reasons, had to plan it such that I was crossing the Great Plains during the peak of tornado season, which is the worst idea ever. What that meant was that I wanted to get across as fast as possible so long as the weather was good. And it’s not just tornadoes, it’s actually massive global warming-inspired flash floods. I showed up in one town thinking, “Oh, there’s a city park. I can camp in it for free.” I get there, and it’s under three inches of water, which someone told me arrived at 1 in the morning in 15 minutes.

So I was like, “OK, between flash floods and tornadoes, I’m doing these 700 or 800 miles as fast as I can,” and I caught great luck. I had very pretty sunny or cloudy, but not tornado cloudy, days. And so I was like, “It’s flat. I can ride 15 miles an hour.” And so I just did 100 miles, 100+ miles a day for seven or eight days in a row.

That’s nuts.

It was pretty nuts. I did take a full two days off at the end of that.

What did you learn about … a lot of things? What did you learn about the country?

We could go on forever about that, and I’m going to have to unpack a lot of that in the book. I guess one thing is that, along the lines of what I’m investigating, which is how people move around, there are large parts of the country where people absolutely are going to need to drive trucks until the sun explodes. When you talk about decarbonizing mobility, there’s parts of the country where people’s work — whether they’re ranchers, whether they’re farmers — they just need really big ass trucks. And so if we’re going to decarbonize that, we’re going to have to figure out a way to electrify them or to have some sort of alternative fuel.

And that’s really interesting because, when you live in New York City, as we do, we have public transit, we have a lot of walking, you can bike. In fact, having a truck is actually kind of like a pain in the ass because it’s impossible to park. And you see these statistics where small trucks have just metastasized the entire category of personal vehicles. They don’t sell small cars anymore. And there’s certain areas where you’re like, “OK, I really get it. They need those trucks.” There are other parts of the country where you’re like, “People are just buying these trucks because they want to feel like a trucker.” When you see a working truck, it looks like it’s been to war.

It’s been put through the wringer, yeah.

Yeah, it’s covered in shit, it’s dinged. And then you see these ones where it’s like you could eat a meal off a side panel, it’s untouched. You’re just burning carbon for no reason, because you want to feel good basically. So it was sort of interesting. That was often suburban stuff. Suburbs, people are just driving these ridiculously over-spec’d vehicles for no good reason at all. The stuff never goes off ground. So on the mobility side, it was interesting seeing that stuff.

I certainly learned the politics are maybe what you’d expect. Cities, you’d see a lot of Black Lives Matter signs and stuff like that, and then you’d get out to the Great Plains and a lot more “Let’s Go Brandon” signs. Although, it was kind of funny, I’d be in these small towns of Nebraska where it’s all, “Let’s Go Brandon,” except for one person who has solar panels and a pride flag. Sometimes I’d knock on the door and be like, “I need to talk to this person. I really want to find what’s going on there.”

That’s brave.

I also discovered, I had never really been out West before, and I got to say, it’s freaking gorgeous out there. I think I really saved the best for last by going out westward. Don’t get me wrong, I love New York City. It’s beautiful and I’m a city person, but I could really understand why people get addicted to living out in the West, because it is just spectacularly gorgeous. So those are some of the things I observed. There’s a lot more.

I’m sure, yeah, we’ll have to wait for the book. And then what did you learn about yourself? You’re dealing with boredom, exhaustion, pain, loneliness, but also moments of zen, euphoria, triumph. What did this do to your body and mind?

It basically helped my body a lot, as you can imagine, because if you do rigorous exercise for five to seven hours a day for 10 weeks, wow. My resting heart rate is in the mid-50s right now. It’s crazy. I’m edging into Marine sniper territory. I think what I learned about myself, there’s a couple things. One is that that because I had spent my whole life being not just unathletic, but sort of faintly opposed to athletics, I’ve regarded them with suspicion. I thought all this sort of personal best stuff was BS, because so much of sports just seemed like an absolute dominance game.

With this ride, I definitely finally got what all the hardcore athletes — the real athletes, not just the howling jocks — what they believe and understand about the power of pushing yourself physically and feeling something really interesting about what it means to be able to handle that. There’s something really exciting about that.

The most intense moment for that was the first big mountain I did, when I went over the Cameron Pass outside of Fort Collins. It was the first time going up to like 10,500 feet, and I had no idea how my body would respond. Because I knew I could probably climb it, I’ve done thousands and thousands of feet of climbing, but I was unsure how I would deal with the elevation, because the air gets very low pressure up there. So I was worried about it frankly. There’s no phone signal. So if you start getting dizzy and weird, I’m riding alone, there’s no one with me, no one to help out.

Discovering that I could do that, and it was wonderful and amazing, in a very perhaps hackneyed way, it was this unbelievable sense of physical confidence and self-reliance. Similarly, traveling like a snail with everything on your bike that you need to survive — here’s my domicile, here’s my tent, I’ve got a bunch of food, I’ve got a thing to cook with — again gave me this wild sense of self-reliance that was really pleasant. These were things that I had not really explored at all before in my life.

Tell me about reaching the coast in Oregon. It read a little anticlimactic in Strava. You had to schlep your bike over to the shore. But what was that moment like?

It felt really amazing, deeply emotional. Because I had spent this whole ride focused on kind of the next day and the next day, I wasn’t spending a lot of time thinking about the far future. Because you alluded earlier to the fact that, how do you plan for this? How do you know where you’re going to stay? Well, what you discover very quickly is you don’t think much more than 24 to 48 hours ahead. You sort of look at the map and you go, “Well, I think I can make it to these three destinations, this campsite, this hotel, this town, this Warmshowers, but we’ll see what the weather’s like, we’ll see what the train is like.” And you don’t spend time thinking two months from now what it’s going to be like when I hit the coast. So in one sense, it’s sort of crept up on me pretty quickly.

What I started noticing was that, in the last couple days, I was having these sharp pangs of emotionality over the lasts. So the last time I was packing up my tent, because that was going to be it, that felt really intense. The last time I said goodbye to people I’d been riding with, because they were going off in a different direction, I was doing the last segments entirely alone, that felt really intense.

And when I saw the ocean… I mean, it’s kind of funny because I arrived in the town where this is the end of it, this is Florence, Oregon, but you can’t actually see the ocean. There kind of was a low comedy of, “How do I get to a beach that will let me actually do my triumphant dip?” But the moment I finally actually saw the water, that was really, really intense, followed by, as you point out, the equally low comedy of realizing it’s very difficult to get a heavy bicycle across soft sand that goes on for a mile. I mean, I literally was carrying the thing.

When I finally got out there and got in the water, that was just quite ecstatic. And I realized I was going to need a picture of this, so I tried taking a selfie and it wasn’t working. So finally I’m like, “OK, I’ve got to get someone to take a picture of me.” And the beach wasn’t really that busy, but there was this group of young women not far away. So I walk over and I’m like this haggard, grizzled, middle-aged dude. I’m like, “Hi, I’m actually not here to rob you… I just want you to take a picture of me.” And they’re like, “What are you doing with a bike out here?” I’m like, “Well, I rode this across the country.” And she was like, “Huh,” not actually particularly struck by it. It was a really, really funny moment actually. She got some great pictures. It was up there along with crossing the Rockies as the key senses of emotional satisfaction and like, “I can’t believe I did this.” People will tell me, “I can’t believe you did it,” and there’s a part of me that can’t believe that I did it either.

I can’t believe you did it. Is there a segment of the ride you’d fly out to do again?

Yes, 100 percent. I would say everything from Wyoming onward was flat-out gorgeous. I would definitely go through Wyoming again. Oregon and Idaho were spectacular. They were this combination of crazy mountains with winding hills. There’s one point in time when I was riding with a bunch of these retired guys that I ran into north of West Yellowstone, and we got to Idaho. You’d climb a mountain for two hours and then you’d be like 4,000 or 5,000 feet up, and then you’d descend 2,000 feet in like 15 minutes. So you’re just coasting downhill at like 35 miles an hour for 15 minutes solid. And it would be these roads that were not just going through big, tall, amazing forests that were on the side of mountains, so it’s rising up, and a valley on either side of you, but you’re winding through it like it’s some sort of video game, and it was so spectacularly beautiful that I just started laughing, because I was like, “This is ridiculous. This is almost too picturesque and this is almost too fantastic an experience.”

If you had to put a figure on it, how much would you say this ride cost you all-in?

The equipment was probably about $3,500, stuff that I had to buy specifically for this trip. The tent. I already had a sleeping bag, but the tent, the bike, a bunch of biking gear, and some cycling-specific clothes, and pannier bags.

And then I guess it’s food and lodging from there, right?

Then it was food and lodging, yeah. The food was not too expensive, because I was honestly just eating pretty cheaply the whole way through, either cooking stuff when I’m camping or eating at inexpensive restaurants. In fact, you get into the middle of the country and stuff is really cheap. It’s not New York. Everything’s half the price of New York City. So you could say it’s whatever your food budget normally is. And then lodging. I stayed for about a third of the time, so for the equivalent to like three weeks, I was staying in hotels, but those hotels often were like $70. They’re not that expensive outside of other things, so you could add another couple thousand dollars on there. I guess totally, like $5,000, $5,500, maybe $6,000.

Now you have to write the book. When’s it due? How’s it going?

It’s going well, because I took a ton of notes while I was riding. So that part, documenting the ride, I feel pretty confident about. But I have another, essentially, year and a half of research to do. It’s due the end of next year. I want to fill in a lot of… There’s reporting, because it’s going to be my story, but then it’s going to teleport out to like, “Here I am at a battery factory for e-bikes, looking at the mines and trying to figure out, can this be made remotely sustainable? Here’s me hanging out at Denver, which is having an epic brawl over bike lanes and people are just fighting.” So just stuff like that. So yeah, end of next year.

Do you see New York ever becoming a more bikeable city?

One hundred percent. It’s gotten so much better in the 25 years I’ve been here. When I arrived in ’98, I had a bike with me from Toronto. And I took one look at the city streets, and I said, “There’s no way I’m biking here,” and I gave my bike away to a friend with a much more cavalier attitude toward spinal injuries. And I did not cycle again for like 12 years. 2010 is when I finally got a bike. So I think things are getting better all the time.

Check out this episode of “Brooklyn Magazine: The Podcast” for more. Subscribe and listen wherever you get your podcasts.

You might also like