Photos by Arturo Sanchez, courtesy of The Hole

The off-kilter seduction of painter Matthew Hansel

Fresh off a run of hit solo exhibitions and with new work in the Armory Show, the artist is having a moment — and so are his inner demons

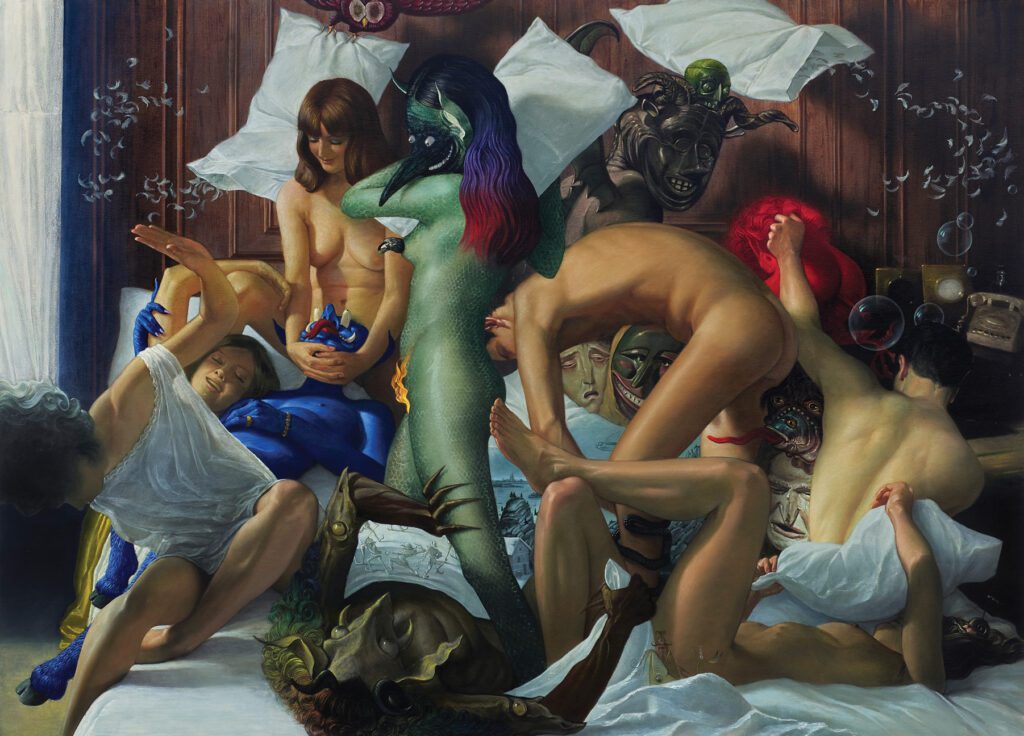

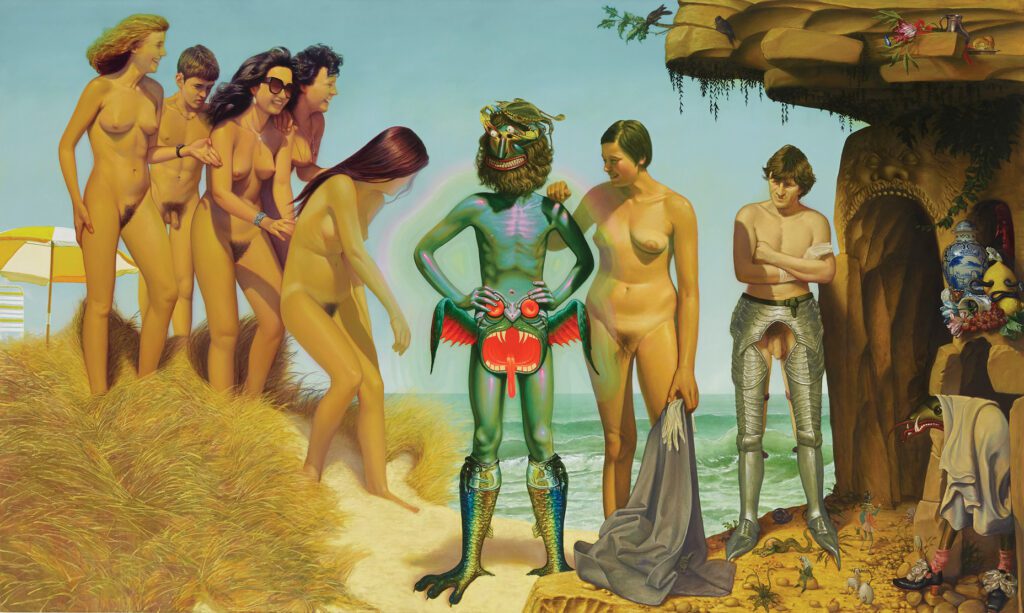

Memory Foam Never Forgets the Fleeting Moments a Lover Regrets, 2021. Oil on canvas. 62 x 86 in

The Greenpoint building that’s home to the studio of Matthew Hansel has a fun house feel to it. Visitors slip off a muggy, industrial street into a twisting, air-conditioned lobby sleekly lit and lined with big, abstract paintings of bright colors in soft aerosol. The uncanny thrives in Hansel’s narrow workspace, which is wallpapered in reference images, with dense thickets of paint tubes on every flat surface.

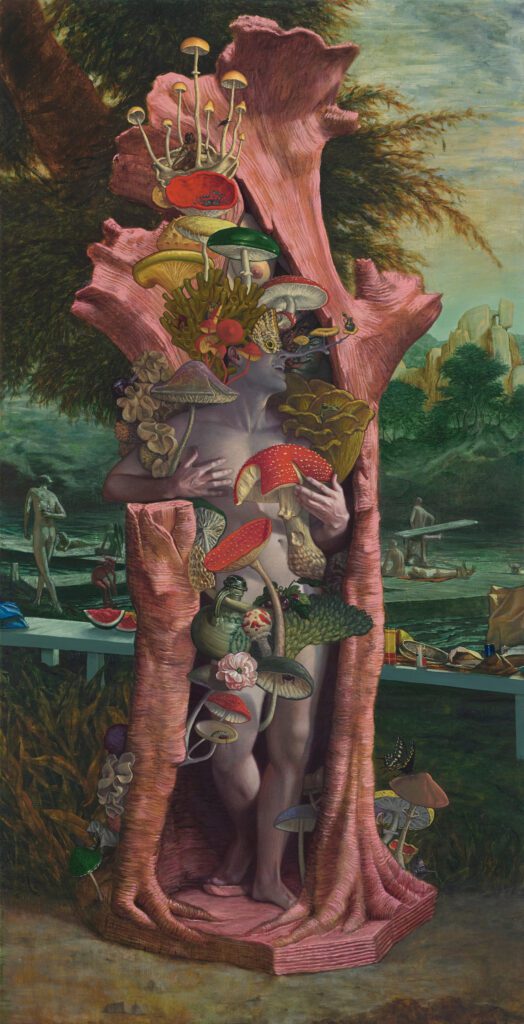

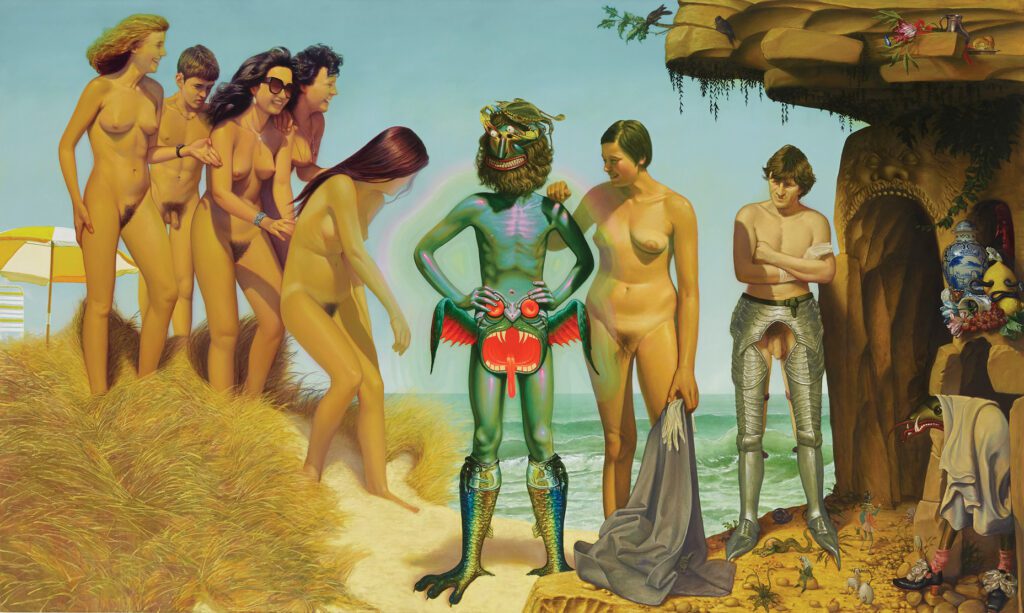

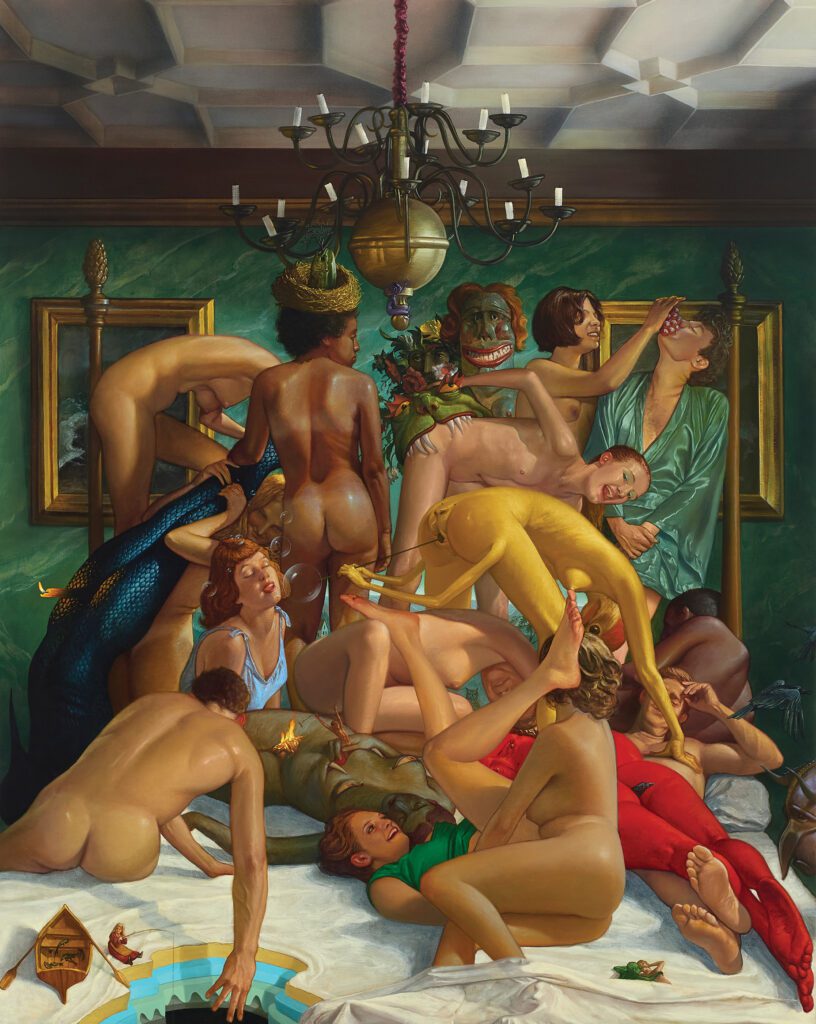

Only a few paintings in progress are on the walls at any time — a large work, a few small ones. Naked beauties, inspired by brochures from the 1960s and ’70s advertising West Coast nudist colonies, cavort on beaches and at house parties alongside various demons. Vibrant still lifes burst with slimy snails and pregnant pears. Painted in oil with vintage-tinged realism and vivid hues, Hansel’s maximalist scenes allure and unsettle.

“I want to seduce the viewer,” Hansel says, “but I like having these things that keep you off-kilter.”

After honing his craft for decades while in academia and during a long detour through the entertainment industry, Hansel has hit a career stride, smashing solo shows at The Hole’s New York and Los Angeles galleries. An objet d’art in its own right, the artist’s first-ever monograph, “Inner Demon Delectatio,” dropped at Printed Matter’s LA Art Book Fair in August.

Recent art press has his back, too. Art Verge has dubbed him “the torch carrier of contemporary surrealism.” Art Now LA gushed that his work is “properly debaucherous.” The Brooklyn Rail considers his aesthetic “equal parts playground and high-stakes morality play.”

This month, he’s got work in the glitzy Armory Show. His latest series, which he started three years ago, clearly resonates, blending technical prowess with a new concept: a paradise where people party with their inner demons.

Society has always been at odds with itself. But our current always-on culture has accelerated and accentuated our fissures. Invisible demons abound. Hansel makes them real. He makes them beautiful and fun, not scary. And his work seems to have finally tapped a nerve.

“It’s difficult and perhaps disheartening to try and gauge success in the art world,” Hansel says. “It’s so fickle and intertwined with the art market — a market that is poor at identifying and rewarding artists who aren’t ‘on theme.’ However, I get immense satisfaction from being in the studio.”

During his 15 years working in film, TV and theater, no one saw the fine art he made. But he kept making it.

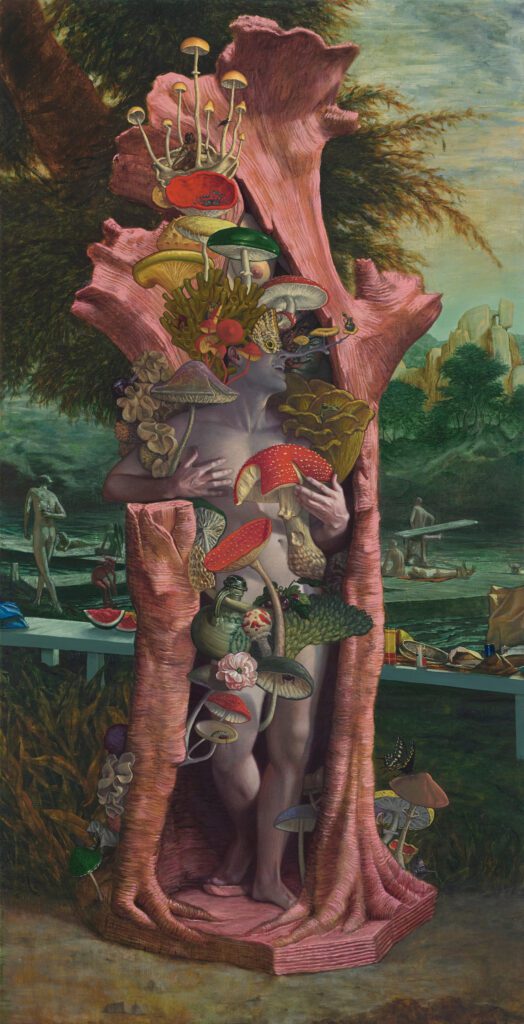

The Mycrophile, 2022. Oil and Flashe paint on canvas. 70 x 36 in

Rockwell meets Bosch

Hansel learned to use color first, and early. Raised in Martinsburg, West Virginia, the 46-year-old knew he wanted to be a painter at the age of 6. He asked his mom to help him learn. She recruited the preeminent local painter, who obliged. Every Saturday morning, Hansel’s mom would take him to the artist’s house. She’d descend in her robe, coffee mug in hand and exuding a whiff of stale cigarettes, to teach him techniques like gradients. She suggested Hansel choose an artwork to recreate. Paging through a Norman Rockwell book from his family’s coffee table, he chose “The Young Lady with the Shiner” (1953). In it, an impish girl with a black eye sits outside the principal’s office.

A friend visiting Hansel’s studio recently remarked that even now his new work echoes Rockwell — with no small nod to Netherlandish Renaissance surrealist Hieronymus Bosch.

In the 1990s, Hansel attended the Cooper Union, when it was still free. He first lived in a dorm at Saint Marks Place and Third Avenue, then jumped around apartments on the Lower East Side. As groups of his friends were moving across the East River to Williamsburg (where Hansel lives now), renting entire houses for just $900, he resisted. “Now if I had the opportunity to live in Manhattan, I would definitely stay in Brooklyn,” he laughs.

Immediately after Cooper, Hansel attended Yale for his MFA in painting — a hot commodity in contemporary art. “The advice I would give anyone, looking back,” Hansel says, “is take a few years between your undergrad and graduate school.” It allows artists to approach the experience as an equal.

He took one theater class at Yale: scene painting. The professor told him about artist unions across the film industry, which could offer Hansel job security within his skill set. With that in mind, Hansel moved back to New York in 2001 to find that the city had changed. He landed in Bushwick more than a decade before Netflix did and lived with his Yale roommate (who was robbed at gunpoint while entering his car one afternoon). Hansel took the union entry exam for United Scenic Artists, Local USA 829, where he’s still a card-carrying member. He passed after a five-round gauntlet that finished with a reality-TV-worthy trial.

“You walk into an airplane hangar that has all these 8-foot canvases stapled to the ground,” Hansel says. Candidates had eight hours to recreate the image they were given, paint mixing and all.

Hansel would go on to paint sets for “Spider-Man 3,” indie films and plays. There was always a slim window of time between when clients got clearance on the image he was to recreate, like, say, a replica Rembrandt for a museum set, and when it was needed. After getting permission from the owner of a work, or contacting an estate to evoke an artist’s style, he’d have just days to paint.

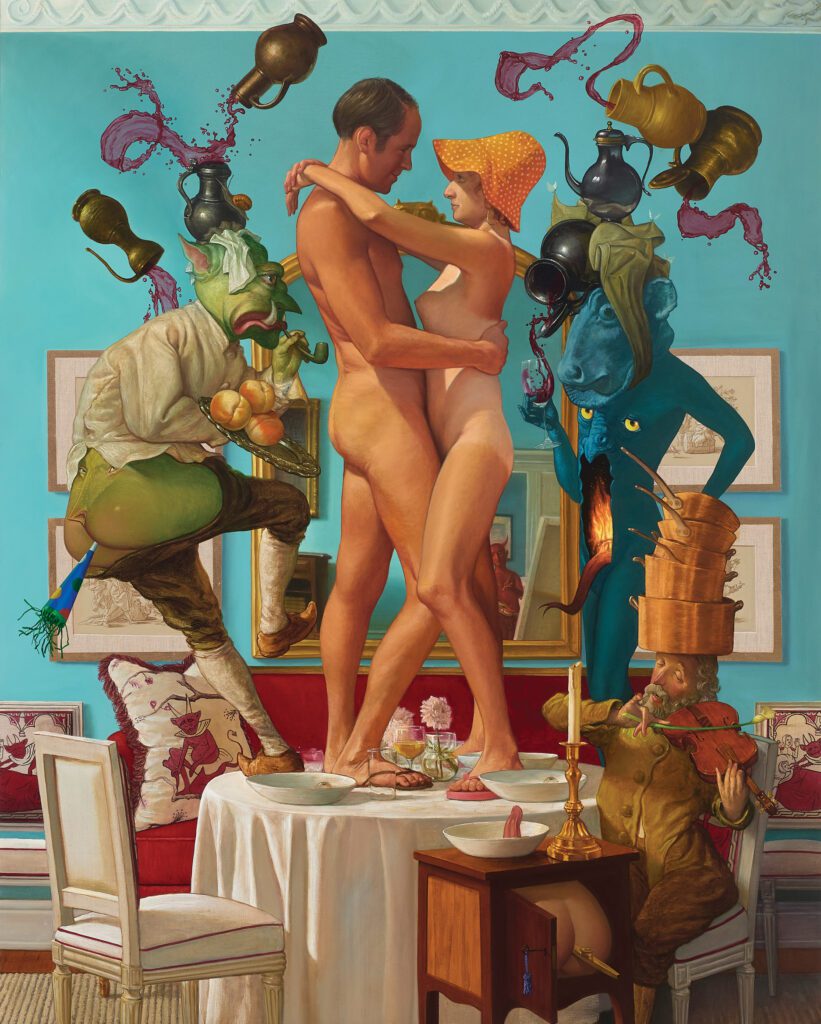

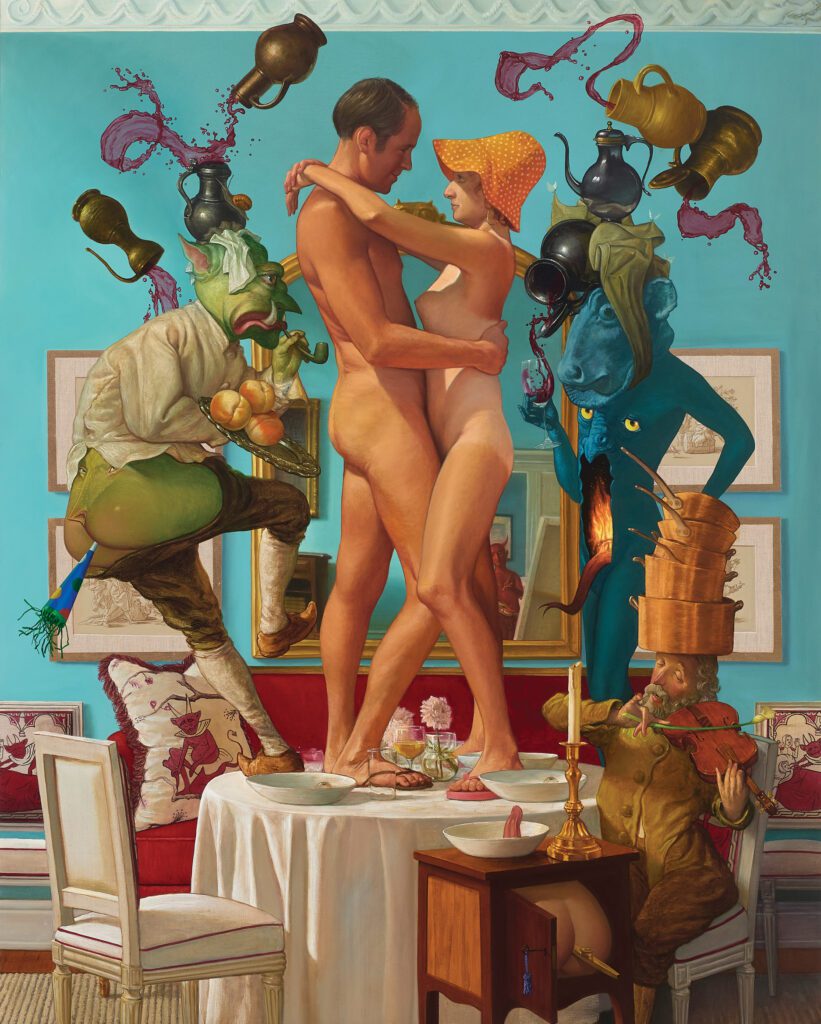

Dancing On The Toes Of Our Shadows, 2023. Oil and Flashe paint on canvas. 70 x 56 in

Working in the entertainment industry was a kind of “baptism by fire” training for the fine art world, despite their maybe shocking lack of overlap. Hansel learned speed but also the sleight of hand film is so known for. He mastered trompe l’oeil, where painted objects look real. He can fake wood grain, marble, a single light source across a whole stage. He learned to mimic oil paint’s effects in acrylic, which is better suited to the stage since it’s fast drying and won’t melt under hot lights.

The switch from film to digital, which captures excruciating detail, only made technical skill more urgent. “If you were painting something that had a bit of impasto to it, you’d have to under-build that,” he says. “Where it would naturally be a big slash of wet oil paint, you couldn’t do that.” Oil paint’s magic is really just chemistry. Color particles, or pigments, suspend differently in oil binders than in acrylic. When oil paint settles, its pigments disperse organically. Light from the canvas carries the colors beneath it. Acrylic paint pigments, meanwhile, settle uniformly. They appear flat without an expert hand.

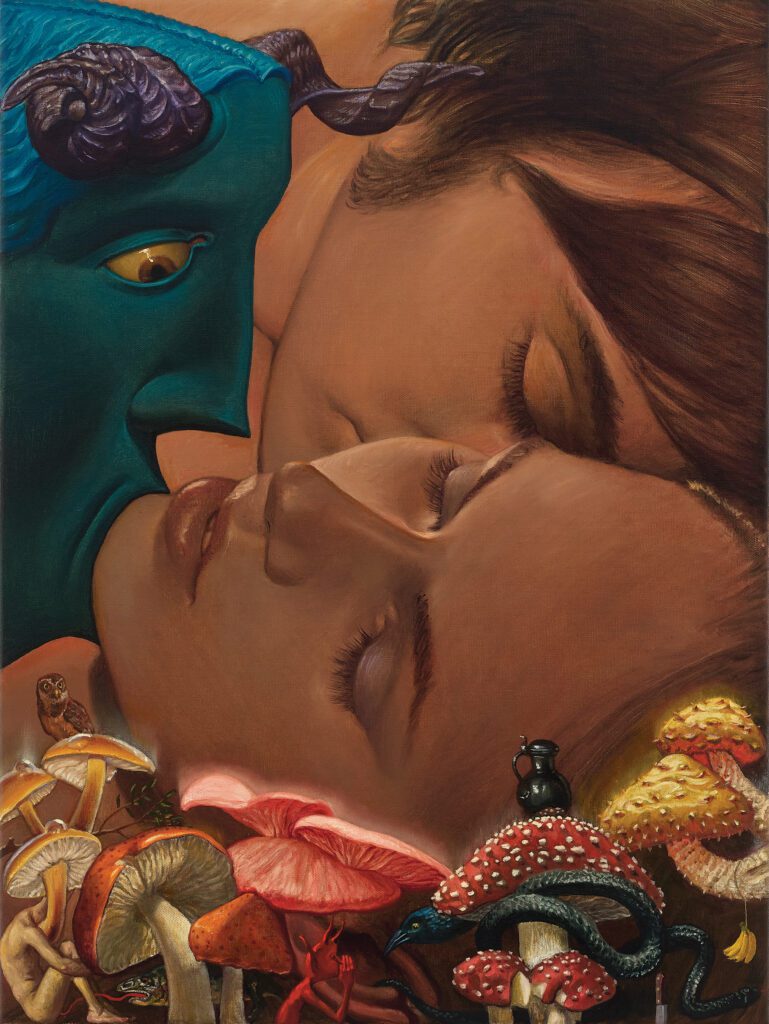

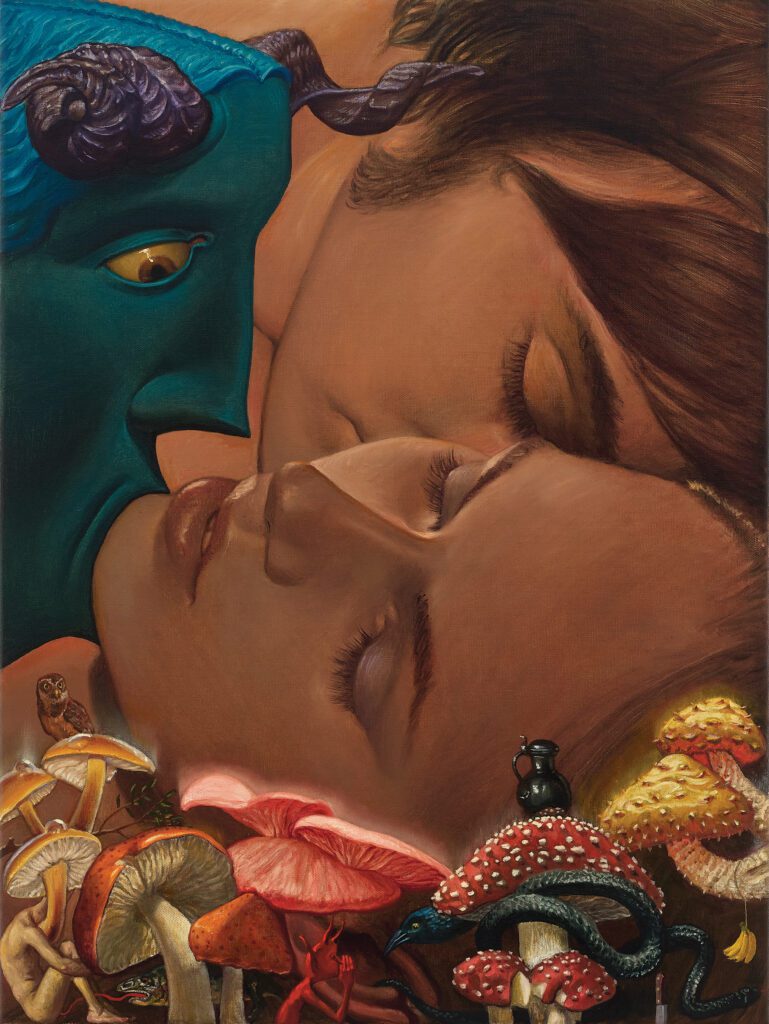

Interlocking Interlocutors, 2023. Oil and Flashe paint on canvas. 24 x 18 in

The Ceremony, 2022. Oil on canvas. 32 x 40 in

Careless Whispers, 2022. Oil on canvas. 40 x 30 in

Ultimately, Hansel spent 10 years in film. It was good money, but he wasn’t getting shows or studio visits. A gallery artist has to play the game.

Then, Sean Landers, another artist and a professor of Hansel’s from Yale, said he needed help at his studio. Hansel took him up on it — and got back into the art world. Landers recalls Hansel’s immense technical talent, which he evinced even in graduate school.

“Many people can acquire skill in painting, but it’s how you use it that matters,” Landers tells Brooklyn Magazine. “Skill can overwhelm meaning if not handled properly. For an artwork to be good, there has to be a marriage of the two, where the combination is more than the sum of their parts. I have seen Matt’s work develop over the past 20 or so years, and he has reached that ground where this is happening.”

‘My Inner Demon Never Sleeps Alone’

The Hole’s founder, Kathy Grayson, first encountered Hansel’s work on the Lower East Side in 2016. At the time, he had been painting collaged abstractions juxtaposing visuals from different eras, from pop art to vanitas.

“You can’t help but be seduced by his old master techniques and, really, what you could call oil paint magic tricks,” Grayson recalls. They did a studio visit, but she wasn’t sure about the work. They stayed in touch, and in 2019, The Hole presented “Giving Up the Ghost,” a suite of Hansel’s historical scenes, some deliberately obscured to disorient the viewer by interrupting their expectation. “It was a qualified hit,” Grayson says, “though it did puzzle a lot of collectors.”

You Don’t Have To Go Home (But You Can’t Stay Here), 2021. Oil on canvas. 70 x 58 in

Then, in 2020, Hansel found himself with an excess of downtime, like the rest of us. During the pandemic lockdown, he ruminated on how everyone was facing their deepest interiors. As a result, he painted two people at the beach, a red demon between them, all laughing. Characters materialized, and the fourth wall fell away as their gazes breached the canvas to meet viewers’. When friends looked at the new work, it elicited the emotional reaction he’d been seeking. In 2021, Hansel debuted 14 more oil paintings from that series in “Inner Demon Delectatio,” his second solo show with The Hole, at their TriBeCa gallery, and the title of his monograph. “If we’d had 100 paintings, we would have sold out,” Grayson says. “The type of collectors that love Hansel are all of them.” Since then, Hansel has had work in art fairs from Cologne to Ibiza. As time has gone on, those pandemic demons have only continued to fuel Hansel, who made headlines in a celebrated beach-themed group show at Nino Mier in TriBeCa this summer. In June, Hansel wrapped “My Inner Demon Never Sleeps Alone,” a solo show at The Hole in Los Angeles that continued his latest work.

A Sudden Reassessment of Man’s Gifts, 2022. Oil and Flashe paint on canvas. 78 x 130 in

It has a meaning to me, but the two people dancing could be anyone. I make most of the painting for the viewer, but there are always parts that I know I’m making just for myself.” — Matthew Hansel

While Hansel says his everyday life impacts his paintings, he avoids representing his experiences literally, employing metaphors at most. He’s never told anyone, for example, that one work in LA (“Dancing On The Toes Of Our Shadows,” from 2023) portrays him and his wife, Elizabeth, in the not-so-distant future, dancing on a table, aged. “It has a meaning to me, but the two people dancing could be anyone,” Hansel says. “I make most of the painting for the viewer, but there are always parts that I know I’m making just for myself.”

Hansel and his then-girlfriend, now wife, moved in 2006 from Bushwick to Williamsburg, where they’ve lived ever since, watching the neighborhood evolve around them. What was once the land of DIY venues and jelly pool parties now has renowned parks and soccer leagues for families, like the one Hansel has with his wife and their daughter, Harper. When the couple moved in, he would’ve figured that having a child would hamper his practice. However, he says, “Having my daughter is the single-best decision I’ve ever made, and my work has only improved since.”

Now Hansel’s fans can bring his work even more intimately into their own homes with the release of his monograph through Canadian publisher Anteism — the same team behind Solange Knowles’ latest book, “In Past Pupils and Smiles.”

Morning’s Light We Can’t Forget, It Warms Us Like An Ember, Illuminating With Regret, The Nights We Can’t Remember, 2023. Oil and Flashe paint on canvas. 70 x 56 in

A Patterned Promised Land (Red), 2023. Oil and Flashe paint on canvas. 70 x 56 in

If You Can’t Be With The One You Love Then Love The One You’re With, 2021. Oil on canvas. 92 x 54 in

Hansel leaned into the historic and fantastical techniques he’s mastered to create the tangerine-hued volume, which boasts drop-cap letters painstakingly designed by the artist. Evocative of illuminated manuscripts of yore, the pages are all foil-stamped and quarter-bound with Cialux Linen. The monograph’s release is capped at 150 copies since it’s so labor-intensive to make.

‘Every artist is a tributary’

The nudity of the figures animating Hansel’s artwork references original sin, vulnerability. Their unclothed glory also draws on traditional Renaissance ideals of beauty, further pairing art history with the contemporary. But Hansel’s got another angle, too — by avoiding clothes, the artist dodges fashion trends, which tend to date a painting. The figures’ tan lines look contemporary, and the hairstyles offer their own clues. He’s seeking time travel. “I think of art history as being a huge river — every artist is a tributary,” Hansel says. “Not only are artists changing the river downstream, they’re changing art from the past. When you see a new artist, you’ll think of an old artist in a different way.”

So maybe it’s appropriate to ask whether this is actually a pivotal moment for Hansel, or if he’s carrying another existing tradition into a new season. Perhaps both.

Where Hansel’s from in Appalachia, he says, people might not think they know much about art. Anyone who thinks that, though, likely knows Rockwell. Maybe even Bosch. Artists don’t normally like having their work compared with others’, but understanding Hansel’s practice through seemingly unconnected greats illustrates how deeply these painters’ styles continue to have an impact on current culture. There’s always a new way to get to know our demons.

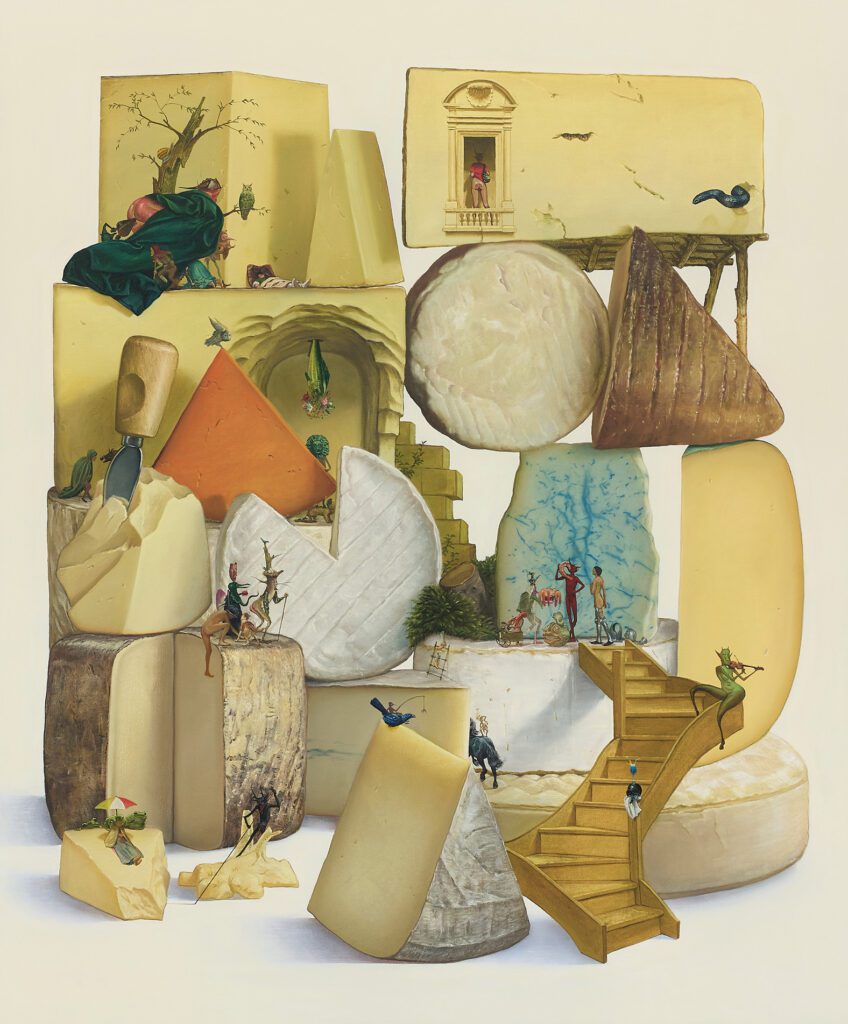

And Hansel is still exploring. His 2021 show in TriBeCa included a backroom of paintings where miniature demons frolicked among stacks of queasily fleshy cheese. Next, he’ll apply illusory painting to medium-sized sculptures of that cheese to explore new dimensions. He debuted his first series of drawings at his recent show in LA, alongside intricate narrative scenes where little demons scurry over thickly woven and ornate rugs, in his further experimentation with micro- and macrocosms.

In the end, these decadent portals offer escape. An artist’s glamour comes at a real-world price, after all. “An artist’s life is one of constant questioning,” Hansel says. “I think the glamour, if that’s the word, comes from being able to do what you love day in and day out. If you can find people who appreciate what you do and value your output, you’re swimming in rarefied waters.”

That kind of satisfaction is timeless and priceless, like feeling totally free while naked among your demons. Says Hansel: “I feel more grateful rather than glamorous.”

We Exclaim Our Desires, Brief Whispers In The Wind, Our Ecstasies Our Instrument, Our Demons Our Delight, 2023. Oil and Flashe paint on canvas. 32 x40 incanvas. 92 x 54 in

This article originally appeared in the fall/winter 2023 issue of Brooklyn Magazine. Want it delivered to your door for a nominal fee (plus a free hat)? Click here to subscribe.

You might also like