A devilish director gets his due: John Waters on 50 years of cinematic chaos

'John Waters: Pope of Trash' opens at the Academy Museum in Los Angeles on September 17

John Waters frequently pauses mid-thought when he’s being interviewed. The bedlamite filmmaker behind “Hairspray,” “Pink Flamingos” and “Serial Mom” gives serious thought to every question, even if he disagrees with its premise. When I suggested Gary Busey’s recent spat of alleged hit-and-runs while sporting a Joker-like smile reminds me of a Waters character, the director politely responds, “I help people get out of jail, not put them in it.”

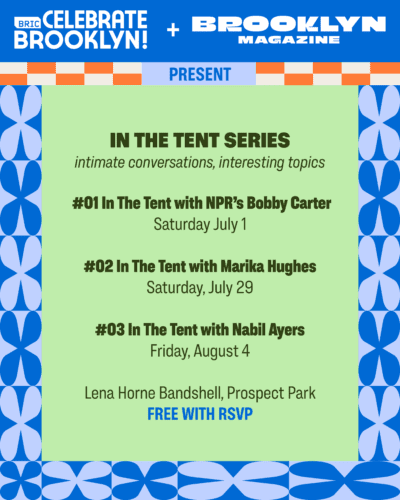

On September 17, cinema’s friend to the degenerates is the focus of a new exhibit at the Academy Museum in Los Angeles, fittingly titled “John Waters: Pope of Trash.” The program runs through August 4, 2024.

It’s an honor Waters couldn’t have expected 50 years ago when he was putzing around New York City, but it’s right up his alley. When he appeared on a cheeky segment of “Lifestyles of the Rich and Famous” in 1993, Waters said of Tinseltown, “Hollywood’s a great place that’s built on insincerity, fake glamour and everything I believe in.” You can expect fake glamour on full display when Waters receives the 2,763rd star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame next week.

Brooklyn Magazine spoke with Waters on the occasion of his new Academy exhibit. He tells us what he did instead of going to classes in New York and how his humor stems from making fun of himself. Waters explains how the 1950s were “horrible” and why he withholds judgment of society’s undesirables.

John Waters (by Greg Gorman)

When you were skipping classes at NYU in 1966 did you ever spend time in Brooklyn?

No, even then I was too old for Brooklyn. I spent most of my time on 42nd Street seeing all the exploitation movies, but then I also went to The Film-Makers’ Cooperative and the whole underground scene.

That was until you were expelled for smoking pot, right? Can you imagine someone being expelled from NYU in 2023 for that?

It wasn’t NYU’s fault, really. I never went to school! I stole books every day and resold them for money to buy pot and make a movie. Because at that time, I don’t think they would have let me make the kind of movies I make. No, I can’t say that because I didn’t go to class, but today they certainly would. So I have nothing against NYU. Technically I was not expelled. The university threw five of us out for pot. I tried to get in touch with some of them to have like a “Big Chill” reunion, but some of them were a little nervous because maybe their current life didn’t know about that thing in their past.

Pat Moran, who’s been my best friend for years and cast all of my movies, I just wrote a letter of recommendation to NYU for her granddaughter, saying at the end, “I promise you she will be a better student than I was.” And she did get in.

What’s the most outrageous item found by the curators of your new exhibit at the Academy Museum?

To me, what’s astounding is the curators Jenny He and Dara Jaffe found things I didn’t even know were in my film archive. I started building it at Wesleyan University in the mid-’80s. I’ve only gone back to look through it when I wrote one of my books, but I didn’t really look at every single thing they have. It was like going into your grandmother’s attic or some crazy hoarder’s place, and they used some really good ones!

I like the little weird items that are so obscure, but you never know what’s obscure in my movies. People come dressed in costume at my summer camp. One year, someone came as the lamp from “Pink Flamingo.” So there’s no detail that’s too obscure. I can’t believe some of this stuff is in the Academy Awards Museum. It’s been wonderfully astounding. I’m just so amazed to see billboards of my face.

‘Pink Flamingos,’ 1972 (Photo by Lawrence Irvine, courtesy of Warner Bros.)

Has preparing the exhibit allowed you to reflect on your career in a meaningful way?

It’s amazing to look back and see all the people in my life. Unfortunately, a lot of the people are no longer with us, so the exhibit is celebrating them and their memory. I couldn’t have done it without the team, the Dreamlanders [Waters’ cast and crew of regulars].

What was it like working with the Dreamlanders?

It was like a political act. We didn’t think of it like that, but looking back, we were like a cell of crazed yippies that hung around with all different kinds of people. We were gay, straight, rich, poor, Black, white because we didn’t get along with people like us! That was where the humor came from, making fun of the rules that we lived by.

I made fun of hippie rules. Believe me, Divine was made to scare hippies and to frighten Earth-shoe types. Divine was the opposite of an Earth shoe. We made it for that audience, but the hippies came and liked to see us making fun of their rules and it’s still like that, in a way. I make fun of gay culture, I make fun of every bit of culture, but I make fun of myself first, and the Academy understands that.

What do you think of being called the “Pope of Trash”?

William S. Burroughs actually said that about me. Hardly am I infallible, but William Burroughs was infallible. No, he did a couple of wrongs, like shooting his wife. He did some really wrong things, but I believe the shooting was an accident.

Do you think the mainstream has come to you?

I don’t think I’ve changed that much, My last movie was “A Dirty Shame,” which got an NC-17 rating. Even the greatest reviews of my last book “Liarmouth” said how filthy it was. So, did I change? No. I think the American sense of humor came a little toward me, but not just because of me.

Some things are so bad that all you can do is laugh and use humor to change people’s opinions. I think that is probably why I’ve had a career that’s lasted this long because I wasn’t mean. I embraced all kinds of people. I wasn’t a separatist. I always said I’d be a good shrink or a good defense lawyer. So that’s maybe what I did in my movies. If I had not been able to have that outlet for all the lunacy that’s in my movies, god knows if I’d try to do any of it in real life.

How has American taste changed since you were a kid in the 1950s?

In the 1950s, you had to be like everybody else. The ’50s were horrible. I mean, that’s why rock ‘n’ roll exploded, that’s why juvenile delinquency happened, because people don’t ever want to be like everybody else. The ones who did usually end up depressed later in life.

I think if you learn to deal with your demons, you’re probably a little more interesting and a little more open to not judging people because you never know their full story. You don’t even know all of yourself — if you’re lucky — and that lets you learn more. Even before you die, you don’t completely understand yourself. That’s why you keep getting up every morning and try to figure it out.

‘Hairspray,’ 1988 (Photo by Henny Garfunkel, Courtesy of Warner Bros.)

Would you say that your love of oddballs, outcasts, and murderers …

I don’t love all murderers! I never said that. I said that I’m interested in what you do if you’ve done something that terrible. How can you ever make it better? And the only way is to make yourself a better person than you would have been if that crime hadn’t happened. That is the only thing. It doesn’t make it better, but that’s all you can do.

Do you extend grace to people that society doesn’t?

I don’t see it as grace. My message about everything is don’t judge other people when you don’t know the whole story, because nobody does. I do believe the opposite of Catholicism, that you’re not born guilty, that everybody’s born completely innocent. And then something happens, and it can be incredibly complicated.

You might also like