ZigZag Records, Avenue U at East 23rd Street, Sheepshead Bay, 2005. ©James and Karla Murray

James and Karla Murray’s evocative, nostalgic signs of the times

A new book of photos pays tribute to NYC storefronts of old — and celebrates the quirky, vibrant places that remain

Vesuvio Bakery, Prince Street near Thompson Street, SoHo, 2004. © James and Karla Murray

New York is a city of villages, each with a distinct temperament, a singular vibe. And everywhere, emblems of this inexhaustible variety hide in plain sight, in bars and bodegas, corner stores and bakeries — small, welcoming worlds of their own.

For husband-and-wife photographers James and Karla Murray, the funky, idiosyncratic styles of those bars and bodegas, corner stores and bakeries, have long served as creative fodder.

The Murrays’ new book, “Store Front NYC: Photographs of the City’s Independent Shops, Past and Present” (Prestel), captures not just the outward aspect but the communal spirit of these places. Two previous volumes of similar work, “Store Front” and “Store Front II,” are out of print — although copies can still be found online for hundreds of dollars. “Store Front NYC,” which comes out September 19 and features a number of recent and older photos not found in the earlier books, is both a summation and an update on three decades of heartfelt work.

Straightaway, the Murrays make clear that this is not another woe-is-us-look-what-we’ve-lost eulogy for a vanished Gotham.

Randy’s Hide-A-Way, Bergen Avenue near Schenectady Avenue, Crown Heights, 2006. © James and Karla Murray

Wallowing in reheated nostalgia is not their thing. Instead, “Store Front NYC” is a chronicle of their countless walks through countless neighborhoods over the years: a natural history of a vibrant, ever-evolving city.

“This project has always been about photographing places that, in the best-case scenario, are still in business,” Karla says. “But what’s important is that every picture represents a small business — some that have gone away and others that have been around for generations.”

The book includes clear-eyed descriptions of the neighborhoods in which the Murrays have worked, along with thumbnail histories of how the neighborhoods have seen their fortunes wax and wane over time — arguably New York’s defining dynamic.

They note of Sunset Park, for example, that “from the 1800s through the early 1900s, its population grew rapidly due to large numbers of Irish, Polish, and Norwegian immigrants who settled there. After World War II, it went into a decline with the closing of the Army Terminal and the rise of truck-based shipping and ports in New Jersey. By 1990, Latinos comprised 50 percent of Sunset Park’s population and helped rebuild the community.”

ZigZag Records, Avenue U at East 23rd Street, Sheepshead Bay, 2005. ©James and Karla Murray

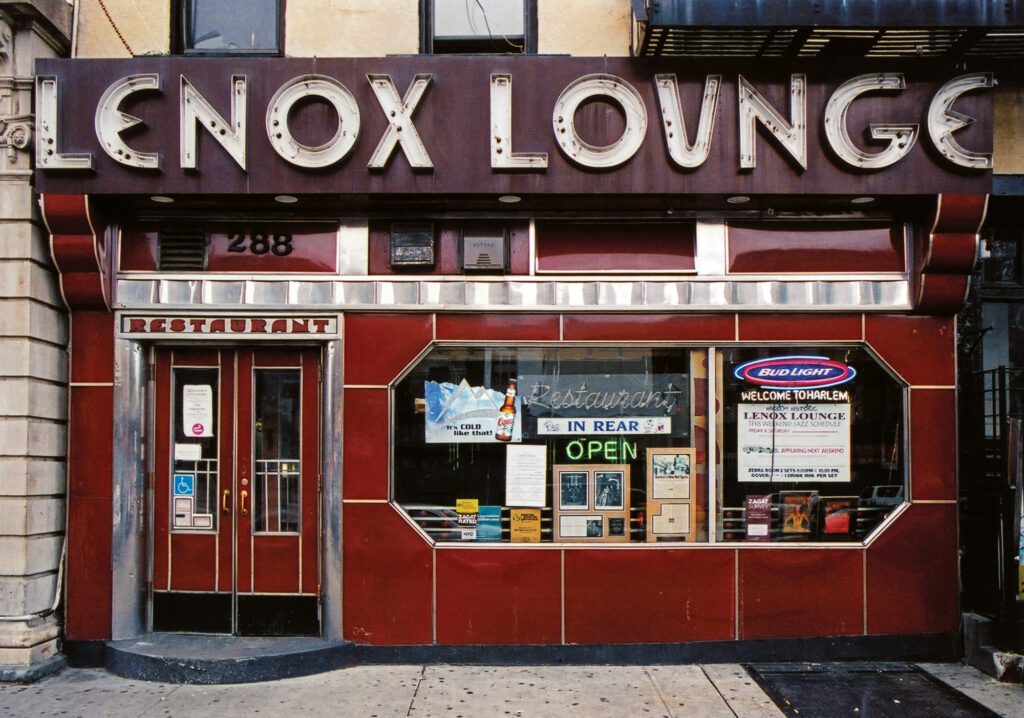

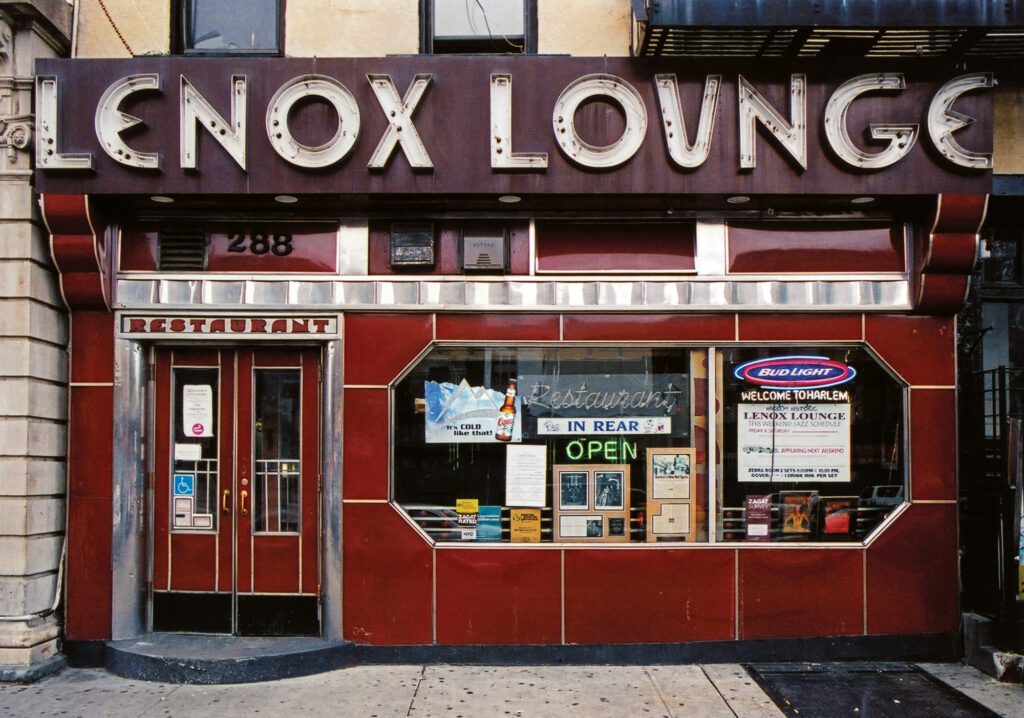

Lenox Lounge, Malcolm X Boulevard near West 124th Street, Harlem, 2004. ©James and Karla Murray

Vincente Reyes Grocery Store, Marcy Avenue at Lynch Street, Williamsburg, 2011. © James and Karla Murray

In a punchy foreword, Blondie co-founder Chris Stein ponders the tectonic changes he’s witnessed, in the city’s landscape and in himself, in the years since he was just another curious kid growing up in Brooklyn. “I find it fascinating,” he writes, “that some old location that I might have ignored for its normalcy I now see as vital. … The flat, undecorated lines of 1960s and ’70s architecture really has the same appeal for me now as an old iron-front loft building in SoHo.”

While the words provide context, “Store Front NYC” is, above all, about seeing what’s in front of us. The pictures are eloquent in their own right and resonate well beyond the five boroughs.

“People contact us all the time, mainly through Instagram, telling us that they love this photograph, or that one,” says Karla. “Some of these folks have never even been to New York, but the city in our pictures is the one they dream about. It’s the New York they’ve always known.”

The source of the photographs’ far-reaching appeal is no mystery: There is a timelessness to them that has nothing cloying or sentimental about it. Beyond that, New York landmarks and street scenes — the Empire State Building, the Brooklyn Bridge, Times Square, the Statue of Liberty, the skyline itself — have long been core elements in our collective visual vernacular, a kind of shorthand for a city where ambition, imagination, creativity and chaos hold sway.

Beautifully framed, lovingly shot, the Murrays’ storefronts are part of that visual vernacular.

Take their photo of the Vincente Reyes Grocery in Williamsburg. The moment they saw the place, James and Karla knew they had to photograph it.

The sense of welcome, and the pride those guys have in the store and in their neighborhood — it sums up a lot about why we started this project in the first place, and why we’ve kept going.— Karla Murray

Tony’s Park Barber Shop, 5th Avenue near 44th Street, Sunset Park, 2006. ©James and Karla Murray

“That picture could have been taken in 1950, or 2010, or yesterday,” Karla says. “The sense of welcome, and the pride those guys have in the store and in their neighborhood — it sums up a lot about why we started this project in the first place, and why we’ve kept going.”

More Brooklyn beauties — Ferdinando’s Focacceria in Carroll Gardens (the city’s oldest Sicilian restaurant, since 1904); Randy’s Hide-A-Way in Crown Heights; Peter Pan Donuts & Pastry Shop in Greenpoint — share these pages with scenes from other boroughs: SoHo’s Vesuvio Bakery, ready for its close-up in a Scorsese film; Schmidt’s Candy in Woodhaven; the late, lamented, Art Deco–inflected Lenox Lounge in Harlem, supplanted a few years ago by an aggressively bland Wells Fargo.

In the end, though, whether or not an individual barber shop, meat market or record store has survived is largely beside the point.

“We didn’t want the book to be an exercise in mourning but more like a celebration, like an Irish wake,” says James. “It’s not a book set in a minor key, with moody shots of neon signs reflected in puddles. The attitude of, ‘Oh, the city I knew is gone, that great dive bar disappeared, St. Mark’s is dead’ — it’s understandable, but it’s not helpful. We want people to know that they can still visit a lot of these places.”

Schmidt’s Candy, Jamaica Avenue near 94th Street, Woodhaven 2010. © James and Karla Murray

This article originally appeared in the fall/winter 2023 issue of Brooklyn Magazine. Want it delivered to your door for a nominal fee (plus a free hat)? Click here to subscribe.

You might also like