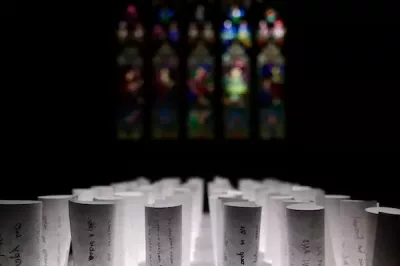

Amara Granderson and the company of '(pray).' (Photo by Ben Arons)

‘Black femmes need to be free’: Playwright nicHi douglas opens up about ‘(pray)’

The National Black Theatre production invites audiences into a church space designed to liberate the Black femme

On a recent chilly October evening, nicHi douglas took us to church. The Brooklyn-based playwright’s new production, “(pray),” presented by National Black Theatre at Ars Nova, is a love letter to douglas’ ancestors — and more specifically to their own younger selves: Many of the questions douglas often worried over as an adolescent are raised and dissected right on stage.

“So much of ‘(pray)’ is me allowing myself to ask the questions that have been on my mind since I was little,” says douglas. But don’t expect to get many answers.

“(pray)” is in many ways an examination of religious inheritance — and the equal amounts of hope and uncertainty that coming to terms with one’s faith can bring. The narrative follows a young congregation member struggling to understand her own beliefs as she simultaneously tackles the transition to womanhood. Through an Afrofuturist lens, douglas presents a hopeful vision of liberation facilitated by community.

Brought to life by a femme-led cast — including Ariel Kayla Blackwood, S T A R R Busby, Ashley De La Rosa, Tina Fabrique, Amara Granderson, Taylor Symone Jackson, Ziiomi Louise Law, Aigner Mizzelle, Satori Folkes-Stone, Gayle Turner, Darnell White and D. Woods — and polished Sunday best looks, “(pray)” coaxes the audience to look within and find what it is that makes them sing.

Brooklyn Magazine sat down with douglas to discuss her experiences with her own faith and the throughline behind most of her work: freedom for the Black divine feminine.

How has Brooklyn influenced your craft and the stories you choose to tell?

I have been living in Brooklyn for about 13 years. I live in Crown Heights and I love it because I’m Jamaican and the community is so Caribbean. When I first moved here, my mom felt really happy that I found this piece of home. I was raised by my mom and was raised to be quite religious. She was raised going to church with her grandmother and that lineage is at the heart of the play. This idea of spiritual inheritance. Why do I and so many other Black women and femmes feel like there should be something we’re doing where spirituality and religion are concerned? Even now in Brooklyn, Sundays are such a quiet and faith-driven day. The small storefront churches that are around the corner from me really come alive on Sunday. I see so many Black women, especially, all dressed up, getting ready to go off to church. Seeing that brings me closer to home too.

Was religion a part of your life growing up?

Because faith and religion were such a big part of my mother’s childhood and her upbringing, she had that calling and she is now an Episcopal priest. She absorbed so much of the religion that she was exposed to growing up — the Episcopal faith. So when she was raising me and my sister, we grew up going to my grandmother’s church. My sister and I went to small elite private schools that were predominantly white. So it was really helpful for us to see a Black church in the neighborhood. It was really foundational in how I ended up understanding my identity as a young Black person.

Is that why you chose this multi-generational approach to telling this story?

In the conversation around spirituality and faith, especially as it pertains to Black women and femmes, you do want to hear the story in a generational way because the experience of how we approach faith, religion, and spirit is so distinctly different between these generations. But it’s from the same soil. It’s like if all of the flowers are different, it’s still the same patch of land. And there’s something really beautiful about that too.

There are a lot of nuances and conflicting emotions that are explored in the play. Why did you choose to examine all of those feelings through an Afrofuturist lens?

It felt important to me to be able to raise a ton of questions but not be too preoccupied with answering any of them. The whole Afrofuturism space can create containers for questioning, imagining and reinterpreting, and so much of “(pray)” is me allowing myself to ask the questions that have been on my mind since I was little. It’s my inner child questions, and it’s even me thinking a little bit about what questions might I have a decade from now. Questions about spirituality, what any of it means, and how much of it we can really even understand in one lifetime. Being able to raise those questions in the mini-community that was formed in the performing company was so important. I feel supported and I feel safe in the community to be able to expose my thoughts and my deep questions about beliefs. And I think that, or I hope, that I have been able to make space for the company members to ask personal questions about the themes of the show too.

What advice would you give to those who may be struggling with their faith, or even in a more general sense, people who may be struggling with creating community?

I may not be equipped to fully answer this, but it’s a beautiful question and I want to step into the challenge. I want to highlight the fact that I relate so much to struggling through questions of faith in religion. I know how hard that is. Journaling has been a massive tool and resource for me in terms of organizing my thoughts. I can look at the writing and try to make sense of the things inside of my head. One of the company members, Ariel Blackwood, started a prayer group. We have a lot of things in common in terms of our upbringing even though we are a full generation apart. Reaching out to people and organizing is important. I think the word that keeps coming up is “organization.” How can you organize your ideas or how can you organize your thoughts in a way that feels productive?

Tell me about the costuming and set design for the play. I really appreciated the immersive setting that welcomed even the spectators into the story, and each outfit was beautifully designed. How did these elements strengthen your message?

I feel so lucky. I’m so fortunate to have been able to work with DeShon Elem, who is our costume designer. She has such a clear and singular design vision when it comes to costumes and her background as a burlesque performer in the past. Also, she’s very into cosplay so she understands the process of telling a story through costume. She brought such flair to these Sunday-best church looks. And the immersive setting just felt necessary to me. To invoke church is to invoke community, in my understanding of church and my belief of what the church is most able to do. We thought, “If we’re gonna talk about church at all, I think everyone needs to feel invited.” And not just invited, but welcome.

Your choreography alongside the music really bolstered that message of liberation. Tell me about why you made choices in the direction and choreography.

Movement and dance are so wrapped up in my creative process in general. I think it would be really hard for me to write something that doesn’t also have a movement or dance component attached to it. I tend to build a movement around words that I want to stand out. In this case, some of those words were, “belief,” “wailing” and “air” — there are six keywords and they built the entire movement vocabulary of the show. In the show, language as technology is a big idea that’s flowing throughout the piece. That is also my way of incorporating Afrofuturism — the movement and the dance are all a manifestation of trying to crack the language. When religious cosmologies and spiritual cosmologies are at play, language becomes even more important. So literally the words and literally the movements that were attached to them took on a life of their own. And I hope that speech through movement was just as legible as the actual writing.

D. Woods and the company of ‘(pray).’ (Photo by Ben Arons)

One of the most powerful tools in the show was the music. It’s an essential tool within the church and is a universal connector in general. Why do you think that music is such an essential tool when it comes to bringing people together, especially in the context of religion?

Music, in a very similar way that dance can hold memories in your body, can transport us immediately. Whether it’s transporting through time or you’re transported geographically to a place or to a memory. That is how S T A R R Busby and JJJJJerome Ellis, who are the co-composers of the piece, conjure feelings. They’re like witches in that way. And I’m so grateful to them for bringing their witchcraft to the show.

You use they/them pronouns as well as she/her. How do questions of sexuality and gender come into play in the work and in your own understanding of spirituality?

I grew up hyper-aware of my gender, and then later my sexuality, and its value in the church. Which is to say, I knew that I was a girl. I knew that if I had questions about queerness/sexuality — and, boy, did I have questions! — that I should keep it to myself! At my beloved childhood Black Baptist church, homosexuality was not ever discussed. The church was also teeming with men in leadership roles. The few women who were leaders oversaw ministries with lower profiles and I was always so disappointed by that. I was desperate for my favorite lady reverends to take the pulpit on Sunday morning. At the Catholic school I attended, we were taught a lot about service and leadership. We were taught to be leaders in our communities. So with “(pray),” I’m allowing myself to speculate as a means to include myself and other queer folk — because we’ve been here. Leading. Raising. Protecting. Pioneering. I aim to model a style of church that could include a gender-fluid femme person like me. I’m gently suggesting that it was both women and femmes that played such a powerful role in how we collectively understand our spiritual inheritance as Black folks. And I’m strongly suggesting that being in a close community with Black women and femmes (and all other Black queer folks) is a necessary component of everyone’s liberation.

What does the true liberation of the Black, feminine divine look, sound, or maybe feel like to you?

One of the ways I try to ignite a conversation around liberation in the work is by replacing the word “father,” in a traditional religious context. And I replaced that with the word “freedom.” And that is because I believe to my core that Black women and femmes need to be free. We need to be allowed to be free in order to have access to spirit. So, to me, the show is trying to demonstrate what that could look like. It invites audiences into a church space that has been designed to liberate the Black femme, to liberate the Black woman. Not just because we say so. But because we are trying. It is us trying to sing together. It is us trying to pray together. It is also us trying to invite our ancestors in.

Creating the space for people to process those things is so important. In your works, you bring about important conversations regarding empowerment through community. Talk about your mutual aid fund, nicHi’s SuSu. So far you have raised over $18,000 for Black artists. What’s next?

NicHi’s SuSu is a wild idea that I had during the pandemic when theaters were shut down and the artist community, especially the Black artists, were really struggling. I attended a Zoom panel that was discussing how to take care of communities in crisis, and one of the tools was mutual aid funding. I had no experience with that but I knew that my community was open enough and generous enough to entertain the idea and that I was organized enough to make this work. So to your question of how will I continue to do so, it’s really a matter of what is needed at the time. And how I can creatively solve that problem. And if I think of a creative solution, I will go to my community and I will ask them. It feels like the least I can do, having been raised to believe that service is as important as going to church every Sunday.

“(pray)” will run through October 28 at Ars Nova @ Greenwich House, 27 Barrow Street. Tickets start at $35.

You might also like