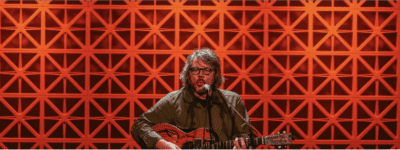

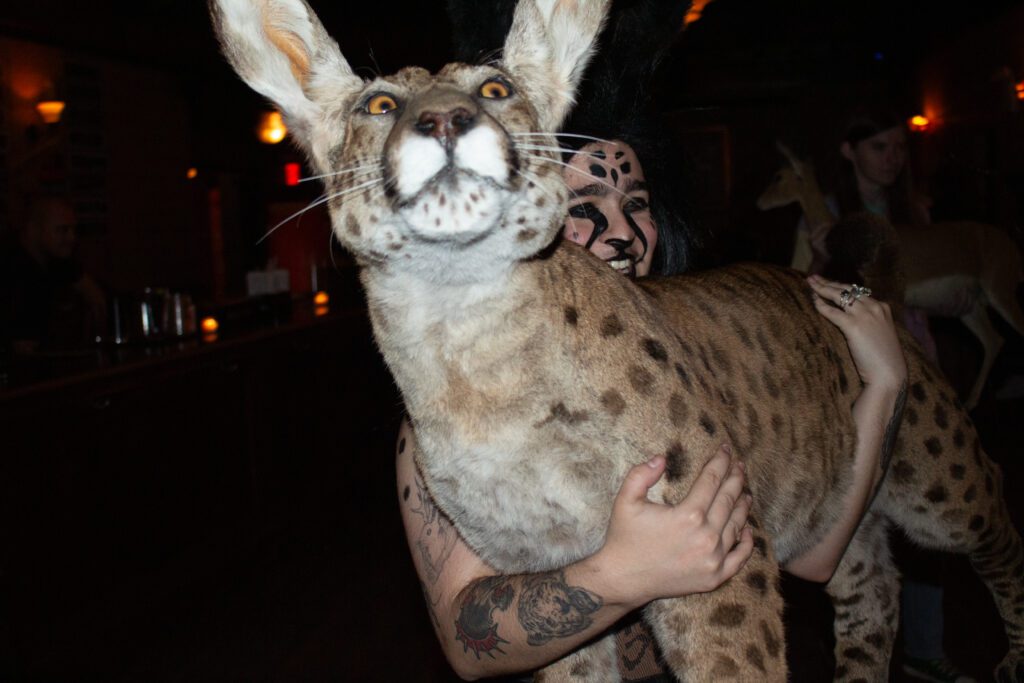

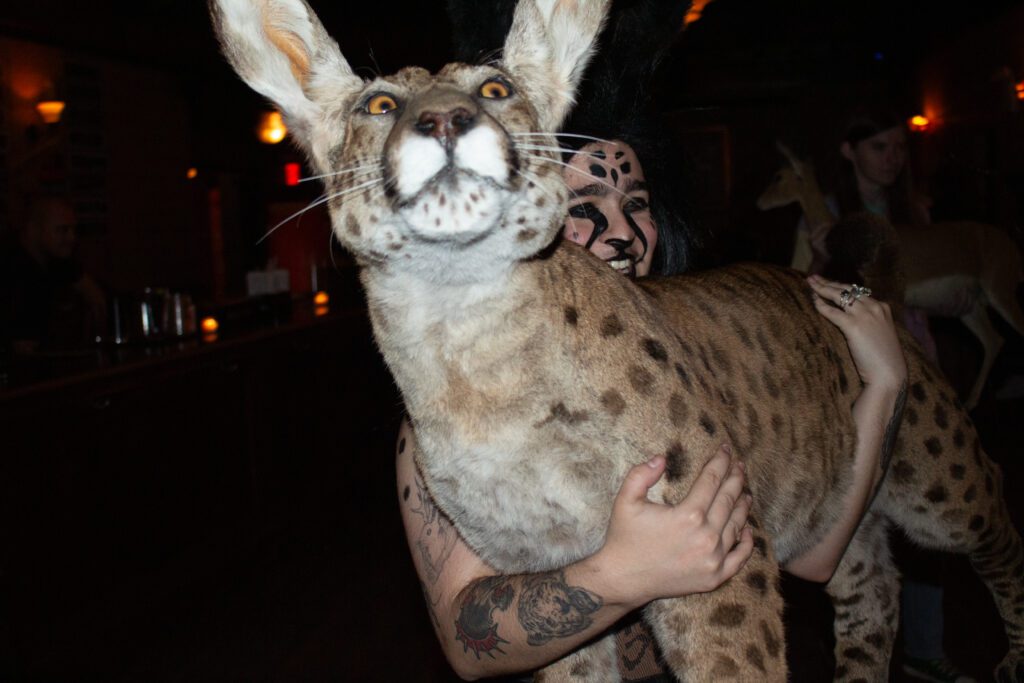

Nick DelCastillo presents his entry: a ‘ranbi' named Ophelia (Arielle Domb)

Taxidermy and drag culture collide at Wunderkammer

Scenes from an evening of ‘telling stories with skin and bodies' at an annual competition at the Bell House

Kat Cunning raises a shiny stiletto heel above Violenza, who is on their hands and knees, blindfolded, cheek pressed against a smattering of silver glass. The performers fall to the ground, kissing each other, their tattoos glowing pink and red under the stage light.

This splash of burlesque by the No Ring Circus would have felt right at home in a Bushwick strip club. But as soon as one notices that the performers are sharing the stage as it does with stuffed peacocks, glitzy raccoons and a gaudy zebra head, it’s clear something else is going on. The performance is in fact the opening act to Wunderkammer, a taxidermy competition at the Bell House in Gowanus.

Cunning and Violenza at Wunderkammer (Arielle Domb)

Founded by Divya Anantharaman in 2018, in part to diversify a hobbyist scene that has been historically dominated by straight white men, Wunderkammer is produced and managed by a team that is predominantly queer and people of color, and is designed to highlight voices that are often overlooked.

“So much of the queer experience is being seen as taboo; being seen as not correct or unnatural,” they add. “I can’t think of anything queerer than turning a dead animal into a piece of art.”

Over the next two hours, more than 20 taxidermists from across the country present their work to a panel of judges — a spectacle which falls somewhere between “Fantasia” and “The Great British Baking Show.” Entries include a crown made of lantern flies, a crucified baboon, midnight black-and-blue butterflies spinning to twinkling tunes like an antique music box.

Madammegrim and Grimvapor present ‘Divination of the restored’ (Arielle Domb)

The taxidermy competition is broken up by a number of drag performances throughout the evening. Shanita Bump uses her stage time to heave a chain of red sausages out of her Victorian garb. Sextia Neight serves a doe-eyed Bambi, with high-heeled boots and fake eyelashes that get ripped off on stage. The commentary on gender — and its mutability — is hard to miss.

Resplendent in red sparkling lipstick, red gloves, a tangle of plastic foliage — orange lilies, purple thistles, tufts of blue forget-me-nots — and three golden green birds perched around their head, Anantharaman jokes, “I went for a more minimalist approach tonight.”

Drag and taxidermy might seem like an unusual combination, but according to Anantharaman, the two artforms are closely intertwined. “Drag is literally a form of taxidermy: Both are all about telling stories with skin and bodies,” they say.

“The performers, just like our taxidermists, are presenting people with questions about the rigid ways we are socialized,” adds Anantharaman. They are both “dismantling binaries, and facing themes like mortality, humanity and connection to the non-human beings in our world.”

Shanita Bump performs (Arielle Domb)

Rogue taxidermy gone rogue

Taxidermy, deriving from the Greek words taxis (“arrangement”) and derma (“skin”) has a long, checkered past: In the Victorian era, taxidermied animals were used as colonial propaganda in natural history museums, evidence of dominion over “exotic” creatures and lands.

But in 2004, the Rogue Taxidermy movement emerged, with a new pop-surrealist philosophy about animal conservation. Members were required to source their animals from deaths not related to taxidermy – a “no kill, no waste” mentality, and artists embraced mixed-mix-media sculpture, as opposed to just traditional taxidermy mounts.

Wunderkammer — a word that literally means “cabinet of curiosities” — picks things up from there and continues to push the boundaries of the artform. Anantharaman and several of the Wunderkammer judges are involved with animal conservation and biodiversity education, and the competition has no clear definition for what is and isn’t considered taxidermy.

Entries at the Bell House last Thursday included prints by Molly Tenzer created with the dead bodies of rats and pigeons found on the streets of New York, and Robin Porter Van Sise’s deer skull, stuffed with Swarovski crystals.

The only requirement is that the work be properly preserved — that it is not rotting, odorous or has an active insect infestation. And that the specimens are legally obtained. There is a zero tolerance policy for illegal wildlife trade.

For many contestants, it’s the inclusive atmosphere that keeps them coming back. “I can count on my fingers the amount of times I really felt like I belonged in a space,” says Nick DelCastillo, who won the competition last year. “One of them was at Wunderkammer.”

Growing up in Florida, DelCastillo says he never felt like he belonged in the world. He came out as trans when he was 15, around the same time he started doing taxidermy, and says there’s a “weird connection” between these two forms of bodily transformation.

“When I started doing taxidermy, I became so much more accepting of myself, started wearing clothes that I actually liked to wear. I stopped dressing hyper-masculine to try and please society,” he says.

“It’s easier for queer people to pick up on aspects of the macabre,” says Wayne Halliburton, who received the runner-up prize last year with “Pussy Whipped,” a cat dressed in a leather harness and an array of cat-themed sex toys.

This year, he’s brought with him “The Great Hop-dini,” a shape-shifting, waist-coated rabbit, whose head he slices off as part of a “magic trick” on stage. “A lot of queer people come face to face with violence or death as part of their daily lives.”

Wayne Halliburton presents his shapeshifting rabbit, ‘The Great Hop-dini’ (Arielle Domb)

Part mountain lion, part bear, part mule

For many audience members, Wunderkammer is their first time seeing drag that isn’t “a glam queen lip syncing Ariana Grande at brunch,” says Anantharaman, “which I also dearly love and enjoy.” The fact that these people return is a “beautiful thing” — “Especially during a time when queerness is struggling between being sanitized for voyeurism and consumption, or being horrifically legislated out of existence.”

Dressing up is celebrated at Wunderkammer — the campier the better. Around the room, the quirks of the subculture appear in flashes. A painted snout. A jeweled cat skull necklace. A lavish fur scarf revealing tiny paws and faces.

Nick DelCastillo has dressed himself up to match his competition entry — as a “ranbi,” a mythical creature that he’s been developing since childhood. “It’s the animal I use to represent myself,” he explains. “I would dress like that every day if I could.”

Part mountain lion, part bear, part mule — the animal defies categorization — a liminality that DelCastillo relates to. “Even in queer spaces, I don’t really always feel like I belong,” he says. “Mostly I’m just telling people that if you don’t fit in the world, if you don’t have a place, if you can’t find comfort in the people around you or in your environment, you’ve got to carve it out yourself.”

DelCastillo and his ranbi (Arielle Domb)

Top honors of the evening goes to a pair of lovestruck white mice, frozen in a “Dirty Dancing”-inspired pose, one held aloft by its partner. It was created by Oh Stuffinell, whose taxidermy adventures include Rock’n’Roll mice racking up lines of white powder and lustful mice going down on each other, and who isn’t present to accept the award.

By 11.30 p.m., most of the guests have begun to pour out onto the street. Among them is Em Maier, a first-time contestant. “We’re all into this weird, crazy, spooky shit,” they say. “We all hang out together, we all have fun, and then we disappear again.”

As midnight approaches, Gowanus’ green-lit backstreets teem with wild animals — a zebra head, a fawn, cat-eared humans. And then they are gone, pulled onto the subway, tugged into Ubers — a mirage from a queer, furry fever dream.

A taxidermy zebra waits to go home (Arielle Domb)

You might also like