'Ti Maché' at MoCADA (Photo by Lul

The ‘counterintuitive’ freedom of Daveed Baptiste

With his current show, ‘Ti Maché,' the designer unpacks the exchanges between colonists and indigenous Haitians

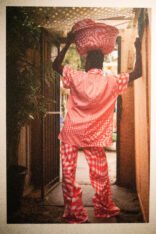

Baptiste’s twist on denim (Photo by Lilac Burrell)

The low ceilings at the Museum of Contemporary African Diasporan Arts (MoCADA) in Fort Greene housed high spirits for the opening night of Haitian-American designer and photographer Daveed Baptiste’s “Ti Maché” fashion show and art exhibit last Thursday. In the welcoming warm lights at MoCADA, guests experienced an abundantly bright energy founded on exploring ties among fashion, migration and colonial exploitation of Black people.

Baptiste chose the name “Ti Maché” for his eighth look collection and fashion editorial photography because it translates to “the marketplace” in Haitian Creole. The exhibit centers on the American cultural exchange and the exploitation of Haitian soil and natural resources. It also tells a very personal story.

“I grew up in [Lakou], and every year when I went back, a new shop or a new home had been destroyed,” Baptiste says. “When I went back to photograph, it was important for me to center the spaces in a way of preserving them in their glory of beauty.”

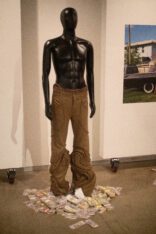

A mannequin stands on a pile of cash (Lilac Burrell)

Extending the marketplace theme, the show

features mannequins, wearing Baptiste’s designs, firmly standing on major Haitian crop exports — rice, corn, coffee beans, sugar, indigo and cotton — and at the gallery’s center, one mannequin stood on money. The designs themselves are a commentary on how wealth and resources are extorted from Haiti for colonial profits. By having his figures stand on the exports, Baptiste reclaims Haitian cultural agency from years of havoc wreaked by U.S. and French imperial colonizers.

Baptiste’s works in a variety of materials, yet none stands out as much as denim, significant for its cross-cultural history. From American iconography and the transatlantic slave trade, it’s easy to forget that denim did not originate in America but was actually made first in Nîmes, France, during the 17th century — hence its name. Denim, being originally French, popularized in America and used here by a Haitian-American artist creates a historical full circle that shows how commercial exchange connects cultures.

‘A duty to speak on it’

Baptiste started brainstorming concepts for what would become “Ti Maché” in 2019 when completing his thesis at Parsons School of Design. Between 2020 and 2022, Baptiste explored fashion by working under Kerby Jean-Raymond at Pyer Moss and at Converse. Through the Converse All Stars Program, Baptiste found the funding to complete “Ti Maché” at MoCADA. Brooklyn was a deliberate and explicit choice to help illustrate displacement of Afrodiasporic people across the world, he says: A third of Brooklyn’s population was Black in 2018, according city data at the NYU Furman Center. And yet, in the decade between 2010 and 2020, Bed-Stuy alone lost more than 22,000 Black residents while gaining 30,000 white residents, according to the most recent census.

(Photo by Lilac Burrell)

“[Baptiste] has a duty to speak on it and I’m proud of him for speaking up,” says Amy Andrieux MoCADA’s executive director. “We’re in this era where Black bodies, especially migrants are being disrespected, exploited — and to be someone who was born in the country, in Haiti specifically, who has had both the duality of experiences of being both Haitian and American.”

Each piece raises the expectations of modern fashion by calling attention to silhouettes, shape and form through texture and dimension. At first glance, his pieces don’t conform to a specific body type or form; therefore; the attention to detail peaks at an almost indifference to binary-gender expectations. Although Baptiste designed his pieces for masculine bodies, the collection is an example of fashion that expands the boundaries of gender presentation.

And of course, pieces like the French Terry hoodie and his puffed pink accordion shirt can be worn by anyone. The shapes of those specific pieces don’t conform to assumptions of man-or-woman clothes, and that complicates how people may define them in terms of gender.

“When I made the collection, I made it with men in mind, but here’s the big but,” Baptiste says. “Yes, I’m maybe thinking in those boxes and in those frameworks, but then when I look at the actual collection, I’m like, oh, OK, like, you had to work in those boxes to get to a point to get to somewhere that was free. Which is so weird because it’s counterintuitive.”

Daveed Baptiste, left, and MoCADA’s Amy Andrieux, center (Photo by Lilac Burrell)

“Ti Maché” will be on display at The Museum of Contemporary African Diasporan Arts through December 3. 80 Hanson Place. Tickets range from $4 to $15, children under 6 get in free.

You might also like