Photo illustration by Johansen Peralta

Burger king George Motz talks new book and upcoming restaurant

Filmmaker, author, TV host and burger scholar George Motz opens up about his career, his favorite Brooklyn burgers and more

Like what you’re hearing? Subscribe to us at iTunes, check us out on Spotify and hear us on Google, Amazon, Stitcher and TuneIn. This is our RSS feed. Tell a friend!

I was sitting at home, minding my own business last Thursday night, when a friend texted me a photo at 9:45 p.m. It was of a man standing at a griddle in front of Farrell’s Bar in Windsor Terrace. Under it was the message: “George Motz Fried Onion Burgers!” And even though I had just eaten dinner, I knew what I had to do. I ran out the door and down the street to Farrell’s and ran up to the griddle and asked for an onion burger. Then I introduced myself to the man who had just flipped his last Oklahoma onion burger of the night.

George Motz is the current reigning burger king. He is the pre-eminent historian of the American hamburger and best known scholar of their different regional styles cultural significance. His 2004 documentary “Hamburger America” was made as a side project, and spawned books about burgers, a TV show about burgers, magazine spreads about burgers, a YouTube series about burgers and, coming, hopefully, in July, a burger restaurant in the Lower East Side. This week, a revised and expanded edition of his 2016 regional cookbook called “The Great American Burger Book” is also being released.

“Why am I not sick of burgers?” he asks me rhetorically. “I had one of my burgers last night and I made a fist pump like, ‘Woohoo!’ And some guy next to me was like, ‘It’s that good, huh?’ I’m like, ‘Yeah, it’s that good’.”

So Motz is this week’s guest on “Brooklyn Magazine: The Podcast,” where he joins me to discuss all things hamburger, with a couple deep dives into some very specific regional burgers. We talk about the history of the burger in America, beginning with its late 19th century state fair roots. And he (reluctantly) shares a few of his favorite Brooklyn burgers past and present.

This interview has been edited for concision and clarity. You can listen to it in its entirety in the player above or wherever you get your podcasts.

You and I don’t know each other. This came together incredibly last minute. We met last night. Literally 13 hours ago. You were out grilling burgers in front of Farrell’s. This sort of pop-up situation you do from time to time. Do you live in the neighborhood?

Yeah, I do. I live in Windsor Terrace. I love this neighborhood so much.

And Farrell’s, of course, an institution, iconic old school Brooklyn working class, hard drinking bar.

That’s what I love about it.

I had the onion burger and the Chester. The onion burger is sort of your specialty, even though it originated in Oklahoma. Now talk about that burger. You were grilling them up en masse. It was 10 o’clock when I got there, and you were… I think I got the very last one.

You actually did. You got the very last burger. We were actually already stopped at that point.

It was fantastic. Talk about that burger.

The onion burger that I’ve been making for years, the one that I make specifically, is very similar, almost exact to the one you can find in Oklahoma. You can find pretty much any part of Oklahoma, mostly west of Oklahoma City, and then south in the southern part of the state. If you ask for a burger at a restaurant, you’re probably going to get the question: “Onion burg?” Because it’s going to be an onion burger. And it’s simply a ball of beef with about the same amount of volume of thin sliced sweet onion, usually Spanish or Vidalia pressed into the patty and onto a flat top, so it all kind of sizzles and melds together. There’s some weird science going on there when you flip it over where the rendered onion juice and the beef fat commingle, and becomes this incredible flavor bomb. A little bit of salt, and that’s it. As you noticed from the burger, you didn’t have to put on any other condiments at all. You didn’t put any ketchup or mustard or anything on there. Though mustard is definitely a good choice.

I took it home. I asked you, “Do I eat this as is or what?” You’re like, “Well, sometimes I put pickles on it, and if you want, mustard.” I did both. It was amazing.

Good. If you’re in Oklahoma and you put pickles and mustard on it, that’s pretty authentic right there. Pretty legit. And the only differences between what I do, there’s actually a couple differences, but the one major difference is that in most cases, if you walk into a place in Oklahoma and ask for an onion burger, it’s not going to have cheese on it. It’s an onion burg, not an onion cheeseburg. I put cheese on mine because people like cheese, and cheese adds another slight level of complexity to a very basic American hamburger.

Before we get to you, which we will get to, let’s get to what I’m guessing our listeners want to know. This is the Brooklyn Magazine podcast after all. What is your go-to Brooklyn burger or burgers?

I know, that’s a tough one. I don’t if you know 282 on Atlantic Avenue. They make a really good green chili cheeseburger there also, which is important. Wow. It’s a tough call though. I don’t have a whole lot of favorites. One of my favorites is gone now. It was called Lot 2, which is sort of South Slope-ish?

Oh, yeah. I loved Lot 2. RIP. Yeah.

That was a great, great burger, but outside of that, it’s really hard to find a good burger. I mean, I don’t know.

Well, the one that’s got all the buzz now, and I love it — it’s a little on the pricier side, but it is simple in the number of ingredients — is the Red Hook Tavern Burger. I don’t know if you’ve had that.

People love that burger. I think it’s a great burger. Well, it’s just the price point. I like burgers that are a little more obtainable, to be polite. And there’s a lot of great burgers in Brooklyn. I never play favorites, just so you know. I don’t do the favorite thing. You just get yourself in so much trouble. My two favorites are closed now, Lot 2 and a place called Korzo, which is closed down.

Oh, I was going to ask about Korzo. RIP also. I took my kid there for the first time towards the end of the Korzo run, not knowing it was the end of the Korzo run, and they fell in love with it, and so we would go back, and then all of a sudden they shut down. But yeah, it was a deep-fried burger.

It’s a good place. They’re friends of mine. Well, it’s actually not a deep-fried burger, which is interesting. It’s a grilled burger, but they wrap it up in lngos dough, and then they’d drop it into the deep fryer. So the only thing that’s really deep-fried is the outside of the bread part. So it becomes sort of this weird deep-fried… The lángos dough is from Eastern Europe. It actually has the consistency, it almost tastes a little bit like a donut. So we used to call it the donut burger, but a donut without the sweetness. So it’s a very popular dish if you just deep-fry lángos bread and put sour cream on it, and that’s usually how they enjoy it and it’s fantastic.

Do you want to go New York wide, Manhattan, borough by borough?

I mean borough by borough. Duffy’s in Staten Island is fantastic. I don’t know if you’ve been there before. In Queens, Donovan’s Pub in Queens is fantastic. I love Donovan’s Pub. In Manhattan There’s JG Melon, obviously the classic PJ Clarke’s is fantastic also. I’m also a big fan of Joe Junior. Joe Junior is a small diner on Third Avenue. No one really thinks about it, because it’s nothing you really think about all the time. There’s no flash to Joe Junior, so it’s not trying to be anything but a diner.

And L.A., oddly enough, has sort of become a hot bed of burger-dom. It’s actually historically relevant in the burger game, but also it’s currently got some heat in the burger space. Of all places Los Angeles, it’s having a moment.

It’s definitely having a moment. I think there’s a reason for that. Specifically, they lifted some of the restrictions on cooking on the street a couple of years ago in LA and then that changed a lot. You don’t have to have permits or anything, you can just show up on the street and cook on the sidewalk. There’s definitely been a moment with the smash burger out there for sure. The competition is fierce. I go out there and I’m like, what the hell’s going on? People are angry. They’re angry about burger culture out there, which is not really my thing, but they really do go deep. And the burgers are all, a lot of them are fantastic. I do have favorites out there, like Mark Tripp, Tripp Burger makes a great burger. He’s got a little bit of bacon in his grind, so it’s perfect. Yellow Paper Burger is fantastic also, I love Yellow Paper Burger. Those are just popups.

I grew up in LA. Well, I get back maybe once or twice a year. Yeah, I always make a point of, you got to hit In-N-Out.

Yeah, of course.

But the Apple Pan. My parents were born in LA, which is an anomaly. They were born in LA in the ’40s, so I grew up with this sort of time capsule. Talk about the Apple Pan for people who don’t know it well.

I mean the Apple pan is a very important place to me because it was the first place that I realized that there could be hamburger culture out there. To me, a hamburger was something you ate at McDonald’s, or Wendy’s, or Burger King when I was a kid. It’s something my dad made in the backyard. It was never more than that. And then I sat down at the Apple Pan for the first time. I was 21 or 22 years old. I was doing a job out there.

For years, I was a union director of photography, and I was out there shooting a job. So I arrived I think at 11 o’clock at night on a Friday, and I asked a friend of “Where should I go?” And it’s like, “Well, it’s only one place to go. You got to go to the Apple Pan.” So I went to the Apple Pan. I sat at the last seat by the pie case, by the pie window. I looked at the guys making the pies, and I looked at the what was going on with the paper caps, and one wall had a red tartan plaid wallpaper. And I thought to myself, “This place is lost in time. How did this happen?”

You walk in the doors and it’s like a time machine. You’re just warped right into the ’50s. And it’s not gimmicky. It’s like, this is probably exactly how it looked, and probably some of the same people still work there. Very little has changed. And then of course they’re famous for the hickory burger. That’s the big one.

Well, they’re famous for the hickory burger and the steak burger, which are two very different burgers that they make at the restaurant. One has a smokey flavor to it from the barbecue sauce, and then one, it’s a steak sauce, it’s like a ketchup, I think. I never get that one. I usually get the hickory.

Can I ask you a stupid question? I don’t want to alienate listeners by talking about LA too much here. What makes a hamburger a hamburger? What makes a hamburger a good hamburger? Those are two different questions, but you can address them however you want.

They are two different questions. What makes a hamburger hamburger specifically is it has to be, and this is defined as, chopped beef, nothing else. No tuna or shrimp or whatever else. It’s chopped beef or ground beef that is cooked somehow and served on bread, period. That’s a hamburger. Whatever you add to it, it becomes more, which that’s the next question. What makes a great hamburger is simplicity. Fresh ingredients. Obviously fresh ground beef, frozen beef is a big no-no. Because of the negative science that goes into freezing beef once you’ve ground it. You can freeze a steak without much degradation of the product, but when you grind beef, it releases a lot of liquid, and when that liquid freezes, it does slightly destroy the flavor of the beef for sure. So I always tell people fresh ground beef, number one. You have to have a really good vehicle. The bread has to be fantastic also. And it should be uncomplicated. And then if you’re going to add ingredients, you’re going to add toppings, do one or two. Don’t go beyond three, that’s for sure.

You don’t like ketchup, I’ve heard.

I do like ketchup. I think ketchup’s wonderful, just not on a hamburger. Ketchup is too sweet. Ketchup is a very, very sweet condiment, and if you put that on a hamburger, no matter how much you put on there, it will completely take away from the rest of the burger. You’re trying to get a beefy experience there. It’s ruined by ketchup, basically.

I tend to agree. This was a recent, in the past decade or so, revelation for me: When you order a burger, just eat it the way it’s prepared. But if you’re going to add something, stay away from ketchup. And growing up, it became habit. Just put ketchup on it. Once I stopped doing it, I was like, “Oh, burgers are a lot better than I realized.”

It’s true. I mean, ketchup is a funny one because I don’t mind ketchup if it’s mixed into a sauce. I know that there’s ketchup in the hickory burger sauce, but it’s more like a barbecue sauce. I mean, what is barbecue sauce, but just basically smokey, spicy ketchup?

There’s a debate that I’ve been having for years with my lady friend. Does the cheese on a cheeseburger have to be American cheese? Certainly it melts better, but does it have to be?

No, not at all. A cheeseburger can be any kind of cheese, but of course the goal is to get it melty. So the meltier cheeses work the best, obviously. It could be Munster, Munster is like butter cheese. I mean, it’s actually really good cheese, by the way, for a burger. Just Swiss, if you get nice thin Swiss, classic Swiss, it’ll melt really well. Meltability is very important. The thing about American cheese that people get confused by is that it’s becomes so associated with the hamburger because it melts fast. I mean, you could almost look at it funny and it would melt. American cheese is designed to melt.

There’s just something synthetic about it. It’s not my favorite. What’s the most common grilling mistake?

Grilling. Literally grilling. People think that grilling is the easiest way to make a hamburger, that they go out in the backyard on the weekend and they’re like a weekend warrior and they can make that burger …

Fire!

Yeah, “Let’s fire, let’s do this!” But actually cooking over a flame is one of the most difficult ways to cook anything. People forget that there’s no controlled environment. You don’t have a flame that you can turn up and down on your stove top. You’re not cooking in an oven where you have a set temperature inside of a box. You’re cooking over an open flame with all kinds of variables that you have no control over, like the wind, and the temperature of the actual air. Where are the coals hottest? If you have a coal in one spot of your grill, I guarantee it is way hotter than even two inches to one side left or right of that coal. It is a very difficult thing to control fire. I always tell people, if you can control fire, you can make a burger on a grill, you are so far ahead of everyone out there.

In all my days of grilling when I had outdoor space on a grill, everyone is like, “Oh, it’s so easy.” And it was like, “Well, no, it’s different every time.” It’s just completely inconsistent.

Every time. Unless you’re doing it all the time, it’s almost impossible to be a master on the grill, especially when it comes to burgers. I’m not 100 percent there. It’s something you have to really focus on. A long time ago, a magazine asked me, what’s your advice for grilling outside? And I said, “Number one, put the beer down.” And it’s absolutely true. If you don’t focus on the 10 minutes it takes to make magic for all your friends in the backyard, it’s all over. You’re going to under cook, overcook. It’s going to be so screwed up. So I tell people, put the drink down, focus on the magic, make it happen, and then celebrate with a drink.

So a question for everyone who’s listening who may not be familiar with your background, which we went through in the intro. Who died and made you burger king?

Actually, there was one, but we were kind of burger kings together. Joshua Ozerski actually did pass away. There used to be two of us, two burger experts. One was a historian that spoke very highly of the hamburger, of the hamburger history, and I was more of the man on the street who was actually going out there and eating these burgers. We were both big fans of each other. He unfortunately did pass away a couple, about five, six years ago at this point.

Okay. Sorry to hear that. I thought it was a lighthearted joke. I didn’t mean to touch any sensitive—

No, all due respect, I definitely would say that he and I were in a way equals, we did a show together years ago. We were back and forth and it was so funny. People were like, “Wow, there’s two of you.” We actually had, there were two hamburger experts in the room. The question is, you could be an expert at anything. You just have to be able to put yourself out there and know these things. I’ve always said that being an expert, it involves two things. It involves passion and knowledge. If you have passion and no knowledge, what are you? You’re a blowhard. If you have knowledge and no passion, it’s kind of useless. But if you have passion and knowledge, which means you can get out there and talk about stuff, you are an expert.

You’re also charismatic, you’re good on camera, but this professional focus on the hamburger started with a documentary. We can go back. You studied history in school, you went into film, you were a DP, as you said. You made this little home spun movie called “Hamburger America” in 2004, which kicked off this leg of your career. It’ll be 20 years next year. What was the impetus of that? What was that film?

That’s amazing. We are celebrating, next year will be the 20th anniversary of the premiere of “Hamburger America,” the film. It was a simple little film. It was designed to be nothing. I was on the road, I was traveling, a director of photography, and every time I would go to a different city, I would try to find the best burger. I had a Sony PD150, if you know what that is. Mini DV was the name of the actual format.

Yeah, I remember those. Yeah, they had a hand crank [Laughs].

It may as well have had a hand crank. I would carry this thing around with me, and I would shoot interviews and I would eat these great burgers, and think, “I’ve got to make something, make some kind of a film about this thing.” I spent two years gathering footage, and then turn it into a film I call Hamburger America, profiled eight different hamburger restaurants in America. And it was a funny little film.

You were just eating at different places and you realized, oh, each region had its own specialty? Or what was it that made you go from, “I’m enjoying eating these burgers,” to I need to document this?

The real reason was because when I would go to these places, I realized that the people who were making these burgers didn’t realize themselves their own importance. They didn’t know how important they were to the fabric of America, and I tried to point that out to them, and I would say, “You’re important,” and they would say, “You’re crazy, just eat the damn burger. What’s wrong with you?” I’d say, “No. I’m telling you right now, no one is keeping hamburger culture alive like this in New York City or L.A.” I mean, they are, but not to the degree you’d find in the Midwest for sure.

I would go out there and find these stories and say, “I need to record them because I know that they don’t appreciate themselves to that degree that I do.” I knew people would appreciate this if I were to get it on camera. Originally, we were talking about doing something with the Food Network, way in the beginning of the Food Network, back in the beginning, and it ended up being bigger than it was, and I ended up making a full-size film out of it, which ended up airing on the Sundance channel and on PBS.

Yeah, and these were early days too. This was before everyone had a food show, and was eating all over the world, and people were aware of regional cuisines versus national cuisines and all that, so the timing couldn’t have been better for this. You were right on that cusp.

There were no internet, there was no GPS. You wanted to go somewhere, you had to pull out a map. You had to call someone on the phone to say, “Hey, I’m coming to visit your restaurant. Can we film?” You couldn’t text them or find their website. I mean, just none of that stuff existed in the beginning. Bit of a pioneer in that respect, to this day I don’t know how we pulled it off in the beginning, because there was really no… I mean, now you just get on your phone and call somebody, look up their information 10 seconds before you get on the phone with them. Oh, there we go. I got you.

Yeah, and everyone’s got Yelp reviews and the foodie boom changed everything too. But of course, around the time you’re filming this, it came out in 2004, but you were filming it obviously before that, and “Fast Food Nation” comes out in 2001. Was that on your radar? It changed my behavior for a couple years.

“Fast Food Nation” was a great book, and honestly that’s what probably provoked me to make [“Hamburger America”], because I was afraid that people were thinking of all hamburger places are like the places they’re talking about in “Fast Food Nation,” which really brings down McDonald’s and all the fast food model at the time.

Accurate, correct. Yeah.

But now, within a couple years later, look what happened? “Supersize Me” came out, and that really screwed us up big time, because that came out the same year as “Hamburger America.” We were trying to get play at festivals. People would say, “Oh, we don’t need another ‘Supersize Me’.” I said, “No, no, no, no. It’s a love letter to the American hamburger.” They said, “We don’t care. A hamburger is a hamburger.” They didn’t know, and we were actually turned down at a lot of festivals because of that.

You were a film guy, not a burger guy, but you were on the road eating, and then this movie happened. Now the movie begets a book, also called “Hamburger America,” which begets a TV show, “Burger Land” on the Travel Channel. Talk about that time in your life where go from a director of photography to, “Oh, now I’m the burger guy.”

It started to take off with the introduction of the film. The film got picked up at the Sundance channel. It got picked up by PBS. People started to call me and ask me my opinion of the hamburger, and I said, well, I’m a filmmaker. I’m not really a hamburger expert. They said, “Well, you’ve been to these places, you’ve been out there in the middle of the country. That makes you an expert.” I said, “Okay.” And then someone asked me to make a book based on my research from the film, and I said, “Well, it’s only eight places in the film.” They said, “Well, can you make a book of 100 great places?” I’m like, “Oh God, okay.” “Hamburger America,” the book, was basically a guide to 100 different places in America.

And then I really started to be asked my opinion about hamburgers and it made sense at that point. I never called myself a hamburger expert. It was the media that called me that. And perfect example, I was watching CNN one day way back in the dark ages, and they had the actual copy on the bottom of the screen, the lower third, was “Lost Luggage Expert.” It was a guy who’s some lost luggage expert. Wow. You can be an expert in anything. So that was it.

Well, I mean, you’ve put in your 10,000 hours.

This guy did too, apparently.

But at a certain point, you must go from feeling like a charlatan, or, “I’m just an enthusiast,” to, “Oh, I guess I know more than most people.”

Yeah. They started to ask my opinion a lot. I began to study more, especially about the history. The one thing that I was not up on was the history. I just knew the histories of these very specific old school restaurants, and I knew about the hamburgers, great hamburgers in America. I didn’t know the actual history. I have developed a hamburger history that is basically an amalgamation of all the other historians that I know, that most of them I’m friends with, and I’ve taken all their histories and put them together, and I’ve done my own research, and I’ve got primary source stuff. I was a history major at school, so to me, pulling together primary sources was the only way to actually create a history of the hamburger.

What’s your biggest scoop or revelation on the history of the hamburger?

I can’t say it’s my scoop, but it’s definitely one I’ve been living on for the last couple of months is that somebody figured out, because every old newspaper magazine, everything is all scanned. A few months ago, somebody discovered that in the Shiner Gazette, April 1894, there was a mention of the hamburger in an ad. Now it makes sense. Back then, nobody was talking about the hamburger. It wasn’t newsworthy. It wasn’t like a new hamburger restaurant opened up. It was a guy who was just advertising in this one section of the Shiner Gazette in Molten Texas, that he was serving hamburgers, I think on Tuesdays or Thursdays, whatever it was. That was it. At Barney’s Saloon.

In 1894. And why is that significant?

Because there really are no written claims to the hamburger, until we started scanning newspapers, and looking at old papers and saying, “Oh wait, here it is. Look at that.” Because before that, there’s so many claims to the invention of the hamburger. It’s kind of annoying, actually, none of them are correct. I mean, because we don’t know. There’s no written evidence. In the beginning, the hamburger was found at state fairs. There were no hamburger restaurants back in the early days. In the 1890s, for sure. There were transient stands at state fairs for the most part.

The original food trucks.

Well, the idea is you go to a state fair and you had to eat something. You were there to buy farm equipment, or to look at cattle, or whatever, or to talk to your friends about your farm practices and animal husbandry. I’m hungry. And you go over to literally the food court of 125 years ago, and they’d be selling everything. They’d have hotdogs. Hotdogs actually predate the hamburger, by the way, in America. I don’t know if you knew that. It makes sense.

My understanding, I could be wrong, was that hot dogs originated in New York, in Brooklyn.

I mean everything came through New York, and eventually as people were looking for more property, more land, they would move west in the migration out to the Midwest. The food went with them.

In the case of hamburgers, then, it comes from Hamburg in Germany. So it’s immigrants who are bringing this. They go to farming communities and the food spreads that way? How does it happen?

It’s as simple as the hamburger came out of the port of Hamburg, Germany, but when it came to the US it was served on a plate. It was actually called a frikadeller or frikadellen, which is chopped meat with spice sometimes put inside, but not really, cooked in a pan, and then served with gravy and potatoes and onions usually. And so you imagine if you’re at a state fair and you’re trying to eat this thing with a knife and a fork, and you watch a hotdog go by on a bun, you’re like, “Whoa, that’s a good idea.”

I can hold it. I don’t need a plate. Yeah.

That’s right. So yeah, the idea, the portability of the hamburg, the actual hamburg plate, I believe that happened at a state fair when literally somebody probably saw someone else walk by with a portable food like a hotdog and said, “We got to do that.” It makes sense.

So how and when did burgers become so ubiquitous? I guess it’s these itinerate vendors with their food carts, and then they just go from state fair to state fair, and then people are like, “I’m going to make that at home.” Or how does it spread?

The hamburger had a rough start. Originally in the beginning it was, like I just said, it was state fairs. Transient. State fair would only be around during the summer.

It was also immigrant food, which is probably looked down upon on some level.

Yeah, it’s ethnic food. It is “dirty,” no one knew where it was coming from. There were mostly Germans who were making these things. First generation German Americans who were making these things were seen as, “I don’t want to eat that. It’s German food.” I’m sure in the beginning if there was some kind of stigma attached to ethnic food and specifically the hamburger. And then something horrible happened. Upton Sinclair wrote a book called “The Jungle,” and it was all about ground beef practices, specifically in Chicago, at the turn of the century.

The original “Fast Food Nation.”

Exactly. No, that’s true. The original “Fast Food Nation.” He was spot on, and it created things like the FDA. It was called it something else before, it became the FDA. That book changed everything. He knew what he was doing. I mean, it was a really, really smart move. So at that point, hamburgers were off the menu, off of people’s radar, because they were seen as really, really dirty food. But people who were wage earners, and the blue collar, the backbone, these people would set up small stands outside of factories and factory workers would come out and eat lunch. They didn’t care. It just tasted great. So it really became known as the food for the working class all the way through up until 1919, 1920 is a very important year, because White Castle was born.

In 1920? I had no idea it goes that far back.

1920. They have the original fast food hamburger. Nothing else predates them because they were the ones who standardized everything. They standardized the bun, the size of the patty. They standardized all the QC, all the quality control that was going into their burgers. It was very upfront. They were very open about how they were grinding meat. At some point in the very beginning, they were actually grinding right in front of everyone. So you could see it was right here. Forget what Upton Sinclair said 20 years ago, we’re doing it in sight.

Amazing. So why is it so bad today?

[Laughs] It’s a good question. I mean, I love those guys. They lost their way. They know it, and it’s really no fault of their own, but they were just going with the flow. They were actually one of the very first restaurants to freeze their meat, and they were stockpiling during the war. That’s why they were freezing.

And that’s probably why they blew up or got so big, I would imagine.

They were the only ones that actually survived the war. Very few restaurants survived World War II, but when they came out, they had stockpiled all this beef and frozen it, so they were able to skate through. Keep in mind it wasn’t just the food, also. During World War II, there were no men, back in the day, to work in the restaurants, because they were all fighting and dying. A lot of restaurants had to close, they had no one to work there, and no beef, and it’s a bad time.

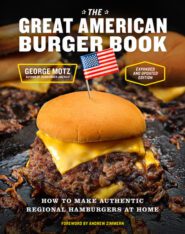

That’s fascinating. Coming out this week, there’s an update to your cookbook, an expanded edition of “The Great American Burger Book.” The original came out in 2016. It’s a regional recipe guide. What’s the update here? I know you’ve been looking at international effects on burger recipes, but what’s the book that’s landing this week, and how is it different from the one that’s already out there?

That’s fascinating. Coming out this week, there’s an update to your cookbook, an expanded edition of “The Great American Burger Book.” The original came out in 2016. It’s a regional recipe guide. What’s the update here? I know you’ve been looking at international effects on burger recipes, but what’s the book that’s landing this week, and how is it different from the one that’s already out there?

The only difference between this one and the one that came out 2016 was that we’ve added 25 recipes. We’ve added over 100 pages. There’s a ton of photos, and it’s the same book, but it’s just expanded, which is great. Because I realized, we went back and looked at the recipes, and they’re all timeless. I mean, they’re not going to change. They haven’t changed, and it works. They all work. So we didn’t change anything. We made a few tweaks here to stuff I said, I don’t believe it anymore.

Like what? What have you walked back?

One I definitely walked back, we talked about smoking. There’s a smoked burger in the book, and back in the day I’d say, “Oh, you soak your wood chips.” And then I wrote the thing and then someone says, “You don’t soak your wood chips.” And they explained the science of soaking wood chips and why you don’t, and I went, “Oh my God, what was I thinking?” Never soak your wood chips people. Don’t do it.

Did you put a caveat on in the new book? Did you say, “I may have said this before, but disregard.”?

I think I did, actually. That was a dumb mistake. I realized that after the book was out for about a week that I probably shouldn’t have said that.

That’s the worst.

But very few though, very few mistakes that we made. There was just typos and stuff like that, but ended up, the book didn’t change much. Here’s the thing, the book is not a hamburger cookbook in the sense that you’re going to go on this exploration of new ideas for hamburgers. I get kind of annoyed by other cookbooks, burger cookbooks specifically, that purport to be “The Burger Cookbook,” and they have things like, oh, let’s make a Hawaiian burger. And the Hawaiian burger has on it pineapples and ham. There is an actual regional Hawaiian hamburger, and it does not have pineapples on it.

Oh, I’m not mad at pineapple.

Well, no, it’s true, but I’m just saying, you got to get it right though. If you’re going to be talking about hamburger history, you don’t put a pineapple on the burger and call it a Hawaiian burger. The original Hawaiian burger is something called a Loco Moco. It’s been around since the 1940s. The Loco Moco is a pile of rice. On top of the rice is a hamburger patty, and then beef gravy, and then a fried egg. It’s awesome.

Is it still made? Obviously it’s still made.

If you go to just about any good authentic diner in Hawaii, you’re going to find it. I believe it was invented on Kauai. Kauai? I think I’m not making that up, but it was definitely somewhere in Hawaii, but back in the ’40s. It was invented by, no surprise, a high school football team.

They need to get those calories in.

You want to know where the pineapple on a burger came from? Canada. It came from Ottawa.

Finally, we can blame them for something. Was that the same with the pizza? The pineapple and pizza. Where’d that come from? Same deal?

That actually came first, and then someone decided to put the pineapple and the ham on a burger.

For the record, I think the debate over pineapple on pizza is silly. I don’t mind it, but…

I don’t mind it either. I just like to get the history correct.

You got to get your facts straight, and then you can improvise. Learn the script before you can riff.

Just to be clear, the book is about hamburger method, and historically accurate hamburger method. Not so much about what’s cute to put on a burger. It’s not about toppings.

It’s the culture, the history, and it’s really interesting to see where food and culture intersects. As people travel, they bring their food with them and then the food gets introduced into new cultures, and then it picks up maybe local flares and flavors. So that’s essentially what you’re doing with this breakdown of the regional burger, is that fair?

Well, and no one had ever done it before either. They’d done it for barbecue, obviously, and there are hotdog information out there about different hotdogs in America. There’s a lot of great hotdogs out there in America. But no one had ever done anything about the hamburger, so I feel like I was a pioneer in that respect, but I also wanted to make sure I got it right. That people were telling their stories about the butter burger or the Michigan olive burger or the green chili cheeseburger in New Mexico, and then I was actually making sure it was accurate.

Yeah, because I guess people assume, oh, a burger’s a burger. What is there to say? But obviously you found out what there is to say. Do you ever get sick of burgers? Have you been like, “I don’t want a burger today?”

No, I think about that often. Why am I not sick of burgers? I had one of my burgers last night and I was like, “Wow.” And I made a fist pump like, “Woohoo!” And some guy next to me was like, “It’s that good, huh?” I’m like, “Yeah, it’s that good.”

Do you travel with a defibrillator or what?

No!

Like, is your health all right?

I exercise. My doctor asked me recently, “What do you do for exercise?” And I said, “I walk a lot.” And he said, “That’s good. That’s good.” So I think it’s very important to get out there and do stuff. People look at me and they think, “You should be a fat guy. You eat so many burgers.” I say “No, but I eat good burgers for starters.” I don’t eat crazy dumb burgers. I don’t eat a lot of processed crap. I do work out when I can. Summertime, I ride my bike a lot, but I also do walk a lot.

What’s a trend you’re sick of.

Well, it’s I think thankfully going away, but I would say unquestionably, the mac and cheese on a burger should go away and never come back. It’s just stupid. The problem is, when you put that thing in your mouth, a hot pasta mixed with your ground beef is not something you really want to get involved with.

Impossible Burger, Beyond Burger, thoughts on that?

I don’t think. I’ve tried it. I mean —

You made a big grimace.

I tell you why. People now finally are agreeing with me that the reason you shouldn’t eat that is because there’s too many damned ingredients in it, and there’s only one ingredient in beef, and it’s called beef. And if you just keep it to a minimum, you’re actually better off having one burger than you are having one impossible burger, and they know it. They’re fully aware of it. I talked to them a long time ago. I talked to Impossible a long time ago. I said, “Obviously you’re gunning for the vegetarians of America.” And they said, “No, we don’t care about them.” At the time, there was only 4 percent of the U.S. that was interested in a vegetarian diet. They said, “We care about the other 96 percent.” They cared about trying to convert carnivores.

You can’t create new habits in people. That’s very, very hard to do.

Yeah, it was tough. I mean, they were just telling me that many years ago. I thought their business model was still out of whack. But I hate to say it, people eat those faux meats just out of guilt. They don’t really taste good. I would much rather, much rather, have a plateful of vegetables than eat that.

Sure. You’re opening a restaurant in July?

Yes, that’s the plan. But you know how that goes. The restaurant, we’re trying to get open as fast as possible. We actually break ground on Monday, we just found out, which is great.

Check out this episode of “Brooklyn Magazine: The Podcast” for more. Subscribe and listen wherever you get your podcasts.

You might also like