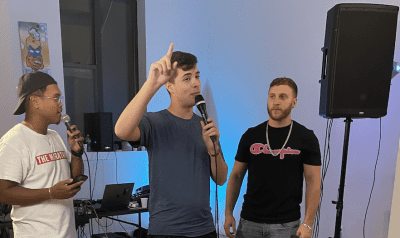

From left: Emily Sieu Liebowitz and Laura Flam (Photo illustration by Johansen Peralta)

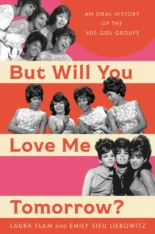

‘They were everywhere’: A new book examines the girl group phenomenon of the 1960s

'But Will You Love Me Tomorrow' is an oral history that tells the story from the view of the women who lived it

Like what you’re hearing? Subscribe to us at iTunes, check us out on Spotify and hear us on Google, Amazon, Stitcher and TuneIn. This is our RSS feed. Tell a friend!

“Will You Love Me Tomorrow,” “”Lollipop,” “Dedicated to the One I Love,” “Leader of the Pack,” “Tonight’s the Night.” You’ve heard the songs, but can you name the groups who sang them?

If history is told by the victors, then our early pop music history as it’s been handed down about the girl groups of the 1950s and ‘60s has been told by the record labels, managers and male rock critics — until now.

“But Will you Love Me Tomorrow” is a comprehensive new oral history of the era of girl groups — the first wave of music by and for teenagers — told by the women who forged the sounds. In a book that spans roughly from the mid-1950s through to the British Invasion, Brooklyn writers Laura Flam and Emily Sieu Liebowitz chart the rise, cultural domination and ultimate disintegration of the girl group sound. They’ve interviewed surviving members of groups like The Shirelles, the Bobettes, the Chantels, the Clickets, the Hearts that you may not have heard of — but you’ve definitely heard. And, yeah, we’re also talking about groups you’ve probably heard of too like the Ronnettes, the Supremes, the Vandellas. Here, we finally get their stories, in their words.

“But Will you Love Me Tomorrow” is a comprehensive new oral history of the era of girl groups — the first wave of music by and for teenagers — told by the women who forged the sounds. In a book that spans roughly from the mid-1950s through to the British Invasion, Brooklyn writers Laura Flam and Emily Sieu Liebowitz chart the rise, cultural domination and ultimate disintegration of the girl group sound. They’ve interviewed surviving members of groups like The Shirelles, the Bobettes, the Chantels, the Clickets, the Hearts that you may not have heard of — but you’ve definitely heard. And, yeah, we’re also talking about groups you’ve probably heard of too like the Ronnettes, the Supremes, the Vandellas. Here, we finally get their stories, in their words.

This week I’m speaking with Sieu Liebowitz and Flam join us on “Brooklyn Magazine: The Podcast” to talk about their book, which sheds an entirely new light on the singers, songwriters, producers, good guys and villains of the girl group era. Designed to be interchangeable and easily controlled by the industry that helped create them, these girl groups were obviously made up of individuals with their own stories, wins, losses, grudges, regrets and sometimes conflicting memories. And, spoiler alert, yes, it turns out we still do love them tomorrow.

The following is a transcript of our conversation, which airs as an episode of “Brooklyn Magazine: The Podcast,” edited for clarity. Listen in the player above or wherever you get your podcasts.

Let’s start by defining our terms. When you talk about girl groups, what are we talking about? And “girl” is actually the right word here. They were very young. Members of The Bobbettes were as young as 12 or 14 on tour. What is a girl group, what do we mean when we say “girl group”?

Emily Sieu Liebowitz: The way that we define girl group is a vocal harmony group of roughly three to five girls, ranging in ages, as you said, as young as 11 to their mid-20s, and they sing in vocal harmonies, mostly coming out of doo-wop and R&B traditions. And the way that we define this genre, though there are girl groups obviously, on either side of this history is roughly from 1955 to 1965, and we consider this the age of the girl group sound.

And it’s really at the dawn of rock and roll. We’re not talking about the Andrews Sisters here. We’re talking about mostly Black, specifically, singers — and we’ll get into the racial component. What’s interesting about the way you set it up, especially in the intro, is that these girl groups were designed from the outset to be interchangeable or indistinguishable from each other in some ways. Literally. The Clickettes would sometimes pass as The Shirelles, if it came down to it. Talk about this defining characteristic. I said in the intro that you’ve heard all of the songs, but you probably didn’t know which name went with which song, and that was in some respects by design?

Laura Flam: It was absolutely, in some respects, by design. Of course, there were things, like everyone wearing the same outfits, that also didn’t help. In terms of the actual girls who voiced the songs and just the material of the songs, every girl was representing every teenager in the entire country. It was such a personal experience with the artist. It was the beginning of rock and roll, and it was the first music that was created for the teen audience. Before that, in the 1950s, there was nothing that was really geared towards teens financially, but also things that teenagers could relate to.

It was, like, Perry Como, right?

Flam: Yeah, exactly, and grownups writing songs about what they imagined that teenagers would be interested in listening to. In terms of young people coming and writing about their own young experiences with crushes, et cetera, this was all new. So people really related to it because it was real and it wasn’t a fabrication. It was what people were really going through.

It’s interesting that you said they were the writers. Not in every respect, they didn’t write all the songs. But some of these girls very young, were actually writing the songs that they were singing, which I didn’t necessarily know was true in a lot of the cases. One of them wrote a song for a talent show and that spurred them into a recording career, unexpectedly or serendipitously, anyway. Can you talk about the fact that some of them were actually writing their own songs?

Sieu Liebowitz: I think the group you’re referring to is The Shirelles who perhaps is the biggest group of the girl groups sound. They have something like nine top 40 hits in a three-year span, but their first song they wrote, as you said, for a school talent show, and many of the urban —

Flam: “I Met Him on a Sunday.”

Sieu Liebowitz: And that goes on to be the first song they record, and the other groups, the earlier groups, we kind of [start] it at 1955. So the earlier groups we cover in the first section, they often came in with their own materials, songs that they were working on together, harmonizing and practicing. So the early groups really did come in with their own material and wrote their songs. The Bobbettes with “Mr. Lee,” which is one of the earliest groups. They received songwriting credit for their song. We really see those opportunities disappear for the girls as the idea of the quote-unquote “girl group” becomes more of a structured specific idea in the music industry’s mind.

Once people smell money, they come creeping around.

Sieu Liebowitz: Exactly.

Flam: That’s when the professional songwriters show up.

And they do show up in this book. So many of these young hit makers never saw a dime. The Shirelles had money coming to them in a trust, but when they came of age it was just not there, which I imagine would’ve been devastating at the time and probably resentment-fueling for years to come. What happened there? Where did this money go?

Sieu Liebowitz: Every group is actually an individual story, and I don’t think that every group has the exact same place it went, but what is true is that many of these groups were actually recording on independent labels and rock and roll was coming out on independent labels. Pop was coming out on independent labels. So in the case of The Shirelles, Florence Greenberg, the founder of Scepter Records, probably used the huge amount of money coming in from The Shirelles to build Scepter records which is actually known now mostly famously for Dionne Warwick’s career. So she used the money to pour into another musician and build her own business. Which is stealing and embezzling. It’s couched in this idea of, “for a greater good” or contribution. So that’s in that specific case, but it is a case by case basis, depending on if they wrote the songs, if they had copyrights and their situation is based on managers and labels and …

Right, if they own the rights and the publishing … But of course, a lot of them were probably too naive to understand the notion of owning your songs or publishing rights. Can you give another example of a girl group who may have, or should have, had more coming to them?

Flam: The Chantels are another group that went through a lot of the experiences that many of the groups went through. Arlene Smith, their singer, was one of the co-writers of the song, “Maybe.” And together as a group, they wrote a bunch of their early stuff, but when the records came out, the writing credit was given to their manager and to the owner of their record label. At the time, these were the first “rock stars,” so people didn’t really understand what the value of these songs was going to be and how much money was in the publishing in the first place. Nobody knew that this was going to be something that 65 years later would be playing in the grocery store every time that you’d go in.

Also, these were teenage girls, so a lot of times, even if they did say, “What’s going on with the business?” It was like, “Don’t worry about it, you’re kids, it’s fun.” The Chantels actually had this incredible record label owner, George Goldner, who was responsible for the presence of Latin music coming into popular music in America, but he was also a habitual gambling addict and he was described in our book and other places as this character who always had a bunch of different games on at the same time, gambling on everything. And he took the Chantels’ money to the track and lost it, and he ended up owing the mob a lot of money and as payment, they took the record label that the Chantels were on, among his other labels, and that was it.

That was the end of their careers. They were teenagers, but when you’re a teenager, you’re not savvy. You don’t know about the entertainment industry. In 2023, teenagers probably know a lot more about the entertainment industry than in the ‘50s. The idea that these teenagers, girls, are going to go and be represented to be able to navigate contracts and publishing rights, they were absolutely walking into the lion’s den, in terms of going into the record industry, which was designed as it was the Wild West back then. It still is, but back then it really was.

Wild West was a good way to put it. The system was archaic compared to now; it’s still a mess. We wouldn’t be having this conversation about money if the songs weren’t pulling in money It was like an atom bomb went off. One thing that keeps coming up in your book is the power of representation, both in terms of feminism and race. We’ll start with feminism. These were real feminist trailblazers, whether it was intentional or not. LaLa Brooks of the Crystals was 15 when she sang “And Then He Kissed Me,” but she had herself never been kissed. Even your book’s title is about sex when you get down to it. Talk about what they did for representation in terms of women and girls and at the dawn of the sexual revolution,

Flam: I don’t think that even the women who were in the girl groups look at their lives and see the amount of contributions that they made to history as clearly as someone will reading the book even necessarily because they were really unintentionally put into all of these situations where they were really pushing a lot of needles forward. I mean, the idea of these girls deciding that they have voices, what they have to say is important, especially about something like sex. I mean, when “Will You Love Me Tomorrow” came out, it was totally groundbreaking. It was banned by the Catholic Church. The idea that a woman would be having sex before marriage and talking about it and feeling like she has rights somewhere in there. Even if it’s just her own feelings was —

Yeah, “Will you respect me in the morning?”

Flam: Yeah, totally revolutionary. So besides the representation of all the other groups who saw the Shirelles on stage and said, “Oh my goodness, that’s going to be me. I want to do that.” And then, went on for decades and decades and did that, there are people who were given a lot of credit in the civil rights movement for showing up and doing things, and these women as girls should be given the same attention in my opinion because they were traveling around the south in the 1950s and early ’60s, the Jim Crow South, putting their lives in danger, and they were introducing Black culture to white audiences and changing people’s minds, and that was important work.

In your book, The Crystals are doing shows in the South where their songs may be a hit, but the audience has no idea what they look like. They’re showing up at shows where people didn’t know they were Black even, and this puts these children, minors — very talented and influential and wonderful minors, but kids — into some very dangerous situations. Can you talk a little bit about any anecdotes that came up through your conversations with these women or any standout moments? I think The Crystals one is pretty remarkable, but I’ll let you go.

Sieu Liebowitz: I just wanted to follow up on the question before that Laura spoke to just really quickly, is one thing that is striking to me, not only were they’re pushing the needle forward, but sometimes I forget how quickly, even though, we have all these rights being taken away from us in the current moment, that how much progress for women was made so quickly in the last half of the 20th century, considering the thousands of years before. And one thing I think of with the women of the girl groups is they were also some of the first women that lived publicly that were considered respectable women in whatever terms that means at the time, the entertainment industry. Women or girls being involved in that was not considered respectable or presentable to society. Whereas these girls went out and really lived life publicly, and that seems like such a small thing now as women and girls who can just go out and be ourselves in public. That was not something that was allowed. You’d have to have companions. You’d have to have chaperones.

Can you give an example of one of these groups living out loud in a way that maybe was revolutionary? You were talking about chaperones. What does that mean really?

Sieu Liebowitz: So when the girls would go on tour, often they were accompanied by an adult either hired or one of the mothers of the other women in the group. Not only at this time was it dangerous for them to travel in the South, but just being women in public was considered somewhat dangerous. The rules that they are given by their predecessors that they meet on the road is a good example. When the girls start going out on tour, the other women on tour that they meet are Lena Horne. Etta James. These huge figures of entertainment, and these women give them really quick lessons on how to stay safe. And one of them is: you don’t go to the bathroom alone. You don’t go on dates alone. You don’t go anywhere alone, and if someone asks you on a date, you say, “We’d love to come,” and you always speak as a “we.” That helped me reflect on all these ways that I internalized ways to stay safe that I just inherited as a woman going to the bathroom with friends. I never thought of that.

I’m having an epiphany over here, like the cliche about women going to the bathroom in groups, but it’s for safety and I feel like a heel for not ever having realized that before, but that’s amazing.

Sieu Liebowitz: They literally had older women on these tours saying, “Don’t do this, don’t do this. Keep your head down here, keep this here.” And these often women were people who even though they were huge figures, maybe not thought of as extremely respectable as these young girls, who were very well-dressed, very presentable, relatively conservative young women.

Flam: Just to continue on in some of what you were asking about some of the situations that they faced, some of the women had started their early years living in the South, and so they were a little less surprised. But for most of the women, they were coming from Detroit, or at least the women we spoke to or the tri-state area, New York, New Jersey, Connecticut. They really didn’t have any idea what to expect and was very confusing for them the idea [that] it wasn’t an accident that a lot of people didn’t know that they were Black artists when their tour rolled into town and their pictures were not featured on their album covers. Because they wanted to be marketable to as big of an audience as possible. A lot of the artists had a really hard time understanding how, “You’ll come to our show, you’ll listen to our music, you’ll smile, you’ll have the best night of your life, but then, I can’t sit next to you and eat lunch” and felt very much like we want to change things. But also, “We’re leaving here in a couple of days and people have to live here.” I think a lot of the girls, especially since they were so young, what their initial idea was, was to stand up for themselves, but [they] immediately realized this is something that people live with every day here and they can’t just leave.

It is shocking to me. Who thought it was a good idea to put them on a bus and send them to the Jim Crow South?

Flam: We’ve spent a lot of time internally talking about a lot of things while working on this book, but one of the things that we talked about is why did people keep on bringing all of these young teenage girls on these tours? It’s one thing in 1956 when the Bobbettes go out and face terrible experiences. The Klan boarded the tour bus. Everyone was hiding them in the back because they were children. I believe they were on tour with Frankie Lymon who was also a young teenager. So for them, there were kids on that bus — and people are so careful about traumatizing kids now — but nobody was really thinking about what something like having the Klan come onto your bus in the middle of the night while driving through the South, [what the] impact of something like that could have.

No one in the book came to any real harm through this. Obviously, I’m not trying to downplay the trauma of experiences like that, but people emerged more or less intact.

Flam: Everyone emerged physically unscathed that we had spoken to. But LaLa Brooks of the Crystals, for example, told this story. She was on tour with Dionne Warwick and Sam Cooke at the time, traveling in the South, and she went to order something and was surprised because they said you have to go around back and basically order through the back alley — you can’t order in the restaurant. So they went around back and she said something to the waitress. Her hand flew and the menu hit the waitress in the face, and then the next thing she remembered, they were running. Dionne Warwick was pulling her. Obviously, Dionne Warwick had more life experience than her. LaLa Brooks was probably 13 or 14 years old when this happened. They were running, they hid her. She heard the sheriff come and were looking for her echoing through the hallway of the venue. Where’s that girl that hit the waitress? And it was really scary. People were still being hung at that time in the South.

And it’s within living memory, which is something that is so striking about this book because you did choose to do it as an oral history. I love your explanation as to why in the intro you did this as an oral history, but a lot of these women, they were so young at the time, they’re still with us. You have some interesting observations about the nature of memory. Some of these women have been interviewed over the years and have their own comments or memories already recorded. Why did you do this as an oral history and what does it tell you about the nature of memory?

Flam: We wanted to do the book as an oral history because we really wanted to create a space for people to tell their own stories. These are stories that happened a long time ago. We aren’t even sure that at the time people were told the same things at the time. So people remember things different way — something that happened two days ago. But something that happened 60 years ago and something that was a big deal? When you are famous in a group, a lot of times there are things that show up and divide people. So we wanted to make sure that we weren’t making decisions about who seemed right, what was the truth, and just giving people the opportunities to speak for themselves in their own voices, telling their own stories.

There are moments in the book where it’s like, “Well, that’s not exactly how I remember it,” or “Here’s my version.”

Flam: People remember things differently that were in the same room, who knows what 60 years of them continuing to think about an event and having it just solidify, further leads people, but the women themselves are great storytellers and there is such an idea of girl groups as just this interchangeable group of people in beautiful dresses and who sang which song, we don’t know, whatever. There are a lot of voices in our book, but we also wanted to make sure that we could differentiate between the different personalities of the different groups, the people in the different groups, and that even though they are seen as interchangeable people, that they are individual people with their own life stories that are unique. Emily and I are two women writing the book and most music writers are men, and I think that it provided a little bit of just different material in terms of what women talk about when talking about a whole life versus what a man would want to talk about. So that gave us, I think, a little bit more of a personal in, in some ways, which was exciting.

You’re part of the same tribe in some ways. You have shared experiences.

Flam: Absolutely, and a lot of what has been written down is in shadows of people like Phil Spector and Barry Gordy who have done so much and are completely incredible. We don’t want to diminish their contributions in any way, but there is a lot of music history that’s written down about who was in the studio, what day, what song discographies when it comes to this music, but when it came time to just talk about life, it was really something that not many people had spoken to the women about.

To your point, history is written by the winners and the winners are often the people with the money or the record label or the influence in the industry. So this is a brilliant way to sort of get around that history written by the people on top situation.

Sieu Liebowitz: Working with oral history was a very fun opportunity for both of us, and I think it was something that definitely started at the outset because as Laura said, we didn’t want to speak for these people. We weren’t alive at this time. Additionally, we wanted to use the skills we had as not being from that time to put some of the stuff in perspective and next to each other in a way that other people’s memories can’t always exist side by side when the people are physically actually in the room next to each other because it would cause a disagreement. In reality, our memories are also history and that is what makes our history is what we remember things to be. And that became a really important part of the oral history format, speaking to these people and making sure that the immediacy and need of them telling their own stories was being met and then, also letting memory live as it exists as much as possible.

I think an example of that, that’s really benign that Laura and I always chuckle about a little bit, is there’s this moment where they’re recording “Iko Iko,” which is by the Dixie Cups and also written by the Dixie Cups and they get songwriting credit for that. They’re in the studio with Redbird Records and that includes Jeff Barry, who’s a Brooklynite, Erasmus High School. And one of the instruments they used came from the Caribbean and several different people claimed it was from their own honeymoon. So, everybody … when they told us this story, everybody involved would say, “Oh, from my honeymoon, I grabbed this instrument,” and we thought it was so silly because it’s such a small thing, but it also shows how people think of their own memories. I had a thing, I brought something to the table, and that should be how we think of memory in many ways. So it was really a privilege to have all of these central figures talking to you and then getting to see all of it side by side. Then, of course there are less benign cases where it’s about why a band broke up or even abuses both monetary, emotional, and all these kinds of different, more complicated human interactions. I always think that the Jamaican honeymoon instrument is a fun example of how memory really does work and function on an everyday basis.

It’s good to have a fun example.

Flam: To continue in that example, actually, I will add that everyone did have a great contribution in that song, but one thing that’s overlooked in the whole conversation [was that] “Iko Iko” was a little offshoot of the session from “Chapel of Love.”

“Chapel of Love” had been written by Phil Spector, Jeff Barry and Ellie Greenwich. And Phil Spector had recorded it a couple of times with his girl groups. The Ronettes had recorded it, Darlene Love had recorded it, I think The Crystals, a bunch of people had recorded “Chapel of Love” and it had never been released because Phil Spector didn’t like it. Jeff Barry and Ellie Greenwich decided to put it out themselves when they met The Dixie Cups who were coming up from New Orleans and the Dixie Cups heard the song and they said, “Okay, do we have to sing it like that?” And they said, “No, do you hear it another way?” And they said, “well,” and they went and they conferred in the corner and then they sang back “Chapel of Love” as a three-part harmony, which is how they sang and which is how we know that song now, and that’s a huge contribution to that song.

That’s a big musical contribution. It’s actually fascinating to go and listen to the other versions of “Chapel of Love” and then to listen to the Dixie Cups version because that three-part harmony, it totally transforms the song and their contribution is important. We say in the intro to our book, “What would the song, Will You Love Me Tomorrow be if it had been voiced by someone else other than Shirley Alston Reeves, the singer from The Shirelles and everything she personally brought to it?” “Chapel of Love” is a great example of just hearing what they brought to it with their own vocal harmony, style and also, a bunch of musicians that they brought down from New Orleans with them, horn players who also really transform the song. Now I hear it and I can’t hear anything other than the New Orleans influence, but it is really fascinating to listen to.

They deserve arrangement credit of some sort.

Flam: They do. They did the vocal arrangements, minimally.

The one name that you’ve mentioned a couple of times is Phil Spector, and I took a certain amount of glee from the fact that it was very gratifying to hear how disliked he was by a lot of the “girls,” now women.

Flam: That’s what we mean by that, girl talk. Nobody calls Phil Spector as sissy. They’re guys who ask them for interviews.

Well, let’s talk about that. I’ve read the Phil Spector biography. Obviously tremendously influential, incredibly talented. I’m not a huge fan of the Wall of Sound myself, but to hear him just torn to shreds by these women was very exciting, especially given where he ended up and what happened at the end.

Flam: He loved surrounding himself with talented people and he loved surrounding himself with strong women and then resented them greatly, I think. I’m talking about Darlene Love and The Blossoms who were basically his house backup group that sang on every song. Not just Phil Spector songs, but everything that was being recorded in LA in the ’60s basically had the Blossoms. So in a lot of ways, they didn’t need Phil Spector. They were going in and doing the “Monster Mash” and so many songs every day. So when they met Phil Spector, he’s this kind of little nebbishy dude from New York, he really surprised them, and they do call him a “sissy” in our book. He was in a lot of ways. He hid behind guns, he hid behind powerful people. He hid behind weak people. It is refreshing just hearing people talk about him on a personal level too.

Just for them to say, “No, I did not like that, man.” There’s a lot of that, which does not discount the fact that he recorded arguably the biggest Christmas album. We’re coming up on the Christmas season now. So your book, obviously a great gift potential, but pair it with the “A Christmas Gift For You From Phil Spector,” which is an all time classic, but can you talk about that album specifically?

Sieu Liebowitz: Yeah, I also wanted to say something a little bit about Phil Spector. Though he surrounds himself with incredibly talented people. He also did hear something and understood the technologies at the time in a musical way that I think did shift things, and I think one thing that he got out of the girl group though that I really enjoy is that the women of the girl groups are self-taught masters of harmony. These are incredibly talented women. So even though he had a lot of bravado, and I think in the music business, people are very intimidated by actually having the goods, sometimes. I think people, especially the women, had such strong singing chops from such ingrained in them that he just wasn’t an intimidating figure and he didn’t have power over them, though he did have an incredible amount of power over their careers. So that creates both very humorous moments and very difficult moments throughout the book. That goes to the Christmas album, which is a really exciting story within itself, but Darlene Love who sings “Baby Please Come Home,” her resurgence is really based in a career as a solo career round of song. And at the time, it wasn’t actually that huge of a success.

The record tanked when it was released because it came out the day after JFK was assassinated.

Flam: Yeah, November 22nd, 1963 was its original release date. So the country was not in the mood. And of course, it was just part of the tradition of Christmas music being written and recorded by Jewish people. Just some of the best Christmas music out there.

Irving Berlin. Yeah, sure.

Flam: Yeah. He put together this Christmas album with all of the artists on his roster, Darlene Love and her group, The Blossoms was also a group called Bob B. Soxx and the Blue Jeans, but he had everybody under all these different names and contracts, et cetera.

Interchangeable.

Flam: Exactly. The girl groups were the Ronettes, The Crystals, and Darlene Love and The Blossoms, and the one original song on that was “Baby Please Come Home” by Jeff Barry and Ellie Greenwich, but it’s true. When that album came out, it tanked, and it wasn’t until it was re-released in the early ‘70s on Apple Records that it just grew its own legs and took off as its own thing. Actually, on November 22nd, 1963, the Ronettes were in Dallas, on the Dick Clark Caravan of Stars Tour, touring all around, and they were there to see the caravan with the president up in their hotel room waiting with everybody else. They never saw him because obviously, he didn’t make it. But also, on the radio at that exact second in Dallas was the Chiffons’ “I Have a Boyfriend,” and that song was interrupted live in Dallas.

But it does show just, at that moment in 1963, which Emily and I always call just the crest of the wave of the girl group sound — 1963, it was when “Be My Baby,” “My Boyfriend’s Back” — was just representing so many teenagers and every group of girls wanted to be in a girl group and join a girl group, and everyone was writing songs for them and producing songs for them. And it was just a huge craze at that time. It shows how relevant at the moment they were. They were everywhere in 1963 at that moment.

Regarding The Ronettes, who you were talking about: Ronnie would ultimately marry Phil Spector. Their story is incredible. I love the origin story of them sneaking into the Peppermint Lounge in Times Square. They call it a “hooker and sailor” bar, which sounds cool to me. And the Twist is all the rage and they sneak in, and that’s sort of their big break. Can you walk us through how The Ronettes made their debut?

Sieu Liebowitz: The Ronettes consists of two sisters, Ronnie Spector, Estelle Bennett later Nedra Talley-Ross. That’s the cousin.

Flam: Two sisters and a cousin.

Sieu Liebowitz: And they come from a family with the last name, the matriarch and the family was the Mobley family, and they all lived in this one area of Harlem, and they had 14 aunts and uncles, and they were all amazing entertainers. So they grew up performing for their family, and it was known from a very young age that these three girls were beautiful. They were talented, and that Ronnie especially wanted to be a star. So they had appeared on the Apollo stage at amateur night and won, when they were children. So they were always hustling, and eventually, they go down to this, as you said, hooker and sailor joint in Times Square dressed alike as they always were.

One of their mothers, Bebe, Estelle and Ronnie’s mom told them to stuff their bra, how to look older with cigarettes and —

Classic parenting advice.

Sieu Liebowitz: Someone comes out the door and says, “Girls, you’re up,” and they take the opportunity to enter the club.

They were mistaken as the group.

Sieu Liebowitz: Yes. Mistaken for a different girl group.

Flam: Joey Dee was performing as the head of the house band at the Peppermint Lounge at the time, and hot with the “Peppermint Twist.” At the time, every group had a Twist record. It was like The Crystals had “Frankenstein Twist.” Everyone had a Twist record. After “Please, Mr. Postman,” “Twistin’ Postman” comes: The postman shows up and they do the Twist. The Twist was the huge craze. Joey Dee invited them up on stage. They played Ray Charles, “What’d I Say?” And tore down the house, and he hired them on the spot to come back and play every night. They were still in school. Their mom was worried about whether their homework was going to get done. The Ronettes definitely encapsulate that New York hustle in a way that not many groups at all ever did. They’re beautiful. They’re street smart. They have a really unique style.

They talk about being mixed race as well, which is a unique experience then.

Flam: Joey Dee did a movie, “Hey, Let’s Twist,” at the time and the Ronettes were supposed to be in it, and they weren’t allowed to because the director didn’t know what to do with them because they weren’t Black and they weren’t white. So in some ways, the Ronettes, nobody really knew what they were and what their race and their origin was, but for them, they came from this huge family, all of these people, all of these performers, and they were already growing up in this huge melting pot of the family. That’s another reason that they really sort of capture the spirit of New York. As Nedra Talley says to us also in the book, and is quoted in the book, a lot of people have dreams in New York that don’t make it. And when you make it, you make it for your whole neighborhood Those dreams are important and valuable to people, and you have to be careful with them. The Ronettes really saw themselves as this neighborhood creation and came out very proudly from alum out of their neighborhood and just won everyone’s hearts.

Again, representation matters.

Flam:Absolutely.

Was it the Ronettes that said, “People always assumed we learned to sing by singing in the church,” which is the assumption a lot of people make. And they’re like, “No, we sang in the streets. We sang at home.”

Flam: “We sang making money exactly,” because their parents would give them five cents and they’d go out and spend it on candy, but that was them being savvy and making money, and they came up with their whole look. It was totally original at the time. Estelle Bennett went to FIT and she loved fashion. She was very inspired by Brigitte Bardot, their hair, their eyeliner.

They were also stunning.

Flam: And also just having a presence. They were so beautiful too, but just having a presence of the big hair, the fringe so that someone in the back of the audience could see you too. Even on stage with that hair,

You’re both clearly tremendous fans of the music. Was there a group or an individual that you were almost too excited to meet? Did you have any fan-girl moments?

Flam: The whole book was a fan girl moment for both of us, and there are those surreal moments like getting a text message from Martha Reeves that are just wild. We worked on this book during Covid. So a lot of the people that we interviewed we haven’t met and we’ll never meet. A lot of them have passed on even since we’ve started working on the book, but in terms of being fan girls, absolutely. I mean, Emily and I, the reason that we even started on this project is that we love the music. The spirit of the Brooklyn Fox, which is described in the book, these concerts.

The Brooklyn Fox was this major theater in downtown Brooklyn that is not there anymore, but played a big role. I’m glad you brought it up because we’re bringing it to Brooklyn, but go ahead. Talk about the Brooklyn Fox.

Flam: There was the Brooklyn Fox, and there were two DJs, Alan Freed and Murray the K, that came along and had these huge rock and roll extravaganzas. It would be like 25 cents because again, it’s geared towards teenagers and the amount of money they have from their allowance. They’d have like eight groups, but it was like Little Anthony in the Imperials, Shirelles, Ray Charles, incredible, incredible performers. There would be newsreels, a movie and then, the same show a few times a day. So the artists that showed up to perform, would be there all day together. They’d just go on and do two or three songs, and you’d go in for a small amount of money. You’d see the eight biggest pop stars of the moment. And these huge, exciting moments. Those are still how those shows are performed. They’re usually held in high schools around Brooklyn on a weekend, places like the St. George Theater in Staten Island, and there’s always a holiday doo-wop extravaganza for example, at the St. George where they’ll have six, seven, eight, doo-wop groups. Sometimes a girl group. Emily and I have seen The Chiffons there. We’ve seen Ronnie Spector there, coming out and doing their songs, and it is like seeing them in the ’60s. Everyone is older, but everyone comes out. They do their songs and they leave and someone else comes out immediately and does theirs.

So we’ve been going to these shows for years, and that’s how we really developed this extra interest in the music, and the artists that we were seeing.

We did a podcast a few months back. Does the name Kenny Vance ring a bell at all to you?

Flam: Yeah. We did not talk to Kenny Vance. We talked to a couple of the guy doo-wopers as they call them, but we really, where we could, try to focus on the women and their stories as much as possible. There were so many things we wanted to make it into the book and then, a lot of the times the test would be, is this a story about the women or is this just a fun story about something else? Absolutely Kenny Vance, I believe that he went to … there are three high schools, in terms of talking about Brooklyn.

There’s like Erasmus and Lincoln or —

Sieu Liebowitz: And Madison are the three main.

Flam: I believe Kenny Vance went to Erasmus with Neil Diamond, Jeff Barry.

Barbara Streisand.

Flam: Barbara Streisand, Clive Davis, Mae West, Artie Butler, who’s another musician that’s been interviewed in our book. There are these three high schools in Brooklyn, Erasmus, Lincoln and Madison, where seemingly so many young Jewish people who went on to become incredibly influential. Judge Judy, Bernie Sanders,

RBG. Yeah.

Flam: Yeah. Absolutely. Harvey Keitel, Carole King, Andrew Dice Clay.

Liebowitz: Carol King and Bernie Sanders were in high school together at the same time, which I like to imagine when I’m walking around.

Crazy to think about it. Well, I’m glad you said Carole King because there are a lot of fun cameos in the book. More fun than Phil Spector anyway. Carole King and Gerry Goffin, Leiber and Stoller. I’m just like, until I die, a huge Leiber and Stoller fan.

Liebowitz: My gosh. Amazing.

I’m relieved that they’re not assholes, apparently only nice things have been said. Neil Sedaka is in the book. You’ve got Ahmet Ertegun and Jerry Wexler of Atlantic making sure that the Bobettes’ songs were copyrighted in the girls’ names that created a publishing company for them. So there’s some good guys here in this book too. It’s not all doom and gloom.

Liebowitz: I think it’s important when we’re looking at exploitation and abuse to also understand these are systems in place. Something we kept hearing over and again is it was business, and a lot of these songwriters, it’s important to note, if they’ve gone on to have success, they were selling away their songwriter rights as well at the time. So they actually didn’t make money directly off of the bulk of their songs in the ‘60s. It’s important to see that even though things can be business as usual, and people were so generous to talk to us from all sides of these perspectives, we tried to be very generous to all of them.

Also, in that, they’re all coming from themselves as the center of seeing how this played out. I think it’s important to realize that a lot of people don’t see business or hold themselves accountable to the way they might treat people interpersonally while money or business is involved, and that that was really important for us to learn on this project too, that it was really a clear division of how they could treat people and what was also acceptable. So I think it was important to measure and give that generosity to everybody we spoke to, because I don’t think people necessarily have the intentions and then don’t even see how their actions can end up doing certain things or oppressing certain people or shifting people’s whole life trajectories. So I think by trying to reach them in their vulnerable moments, in moments of care, we can see where us ourselves maybe do that in our everyday life as well.

That’s a big way of thinking about it, and I think it sort of ties into something that I had wanted to ask about. A lot of these women were so young at the time that they aged out, tastes changed. They’re not in the music industry anymore. They had careers as school teachers or bus drivers and living among us as these former superstars. Was there a sense of, “it was so long ago, it feels like someone else” or having lived a life well or feeling bitter or was there a little bit of everything?

Flam: You asked earlier actually about whether people’s perspectives had changed through the years, which I thought was an interesting question because one of the things that we did was read — whatever, autobiographies, et cetera, were available to us, obviously. And there was a time in the ‘80s and early ‘90s when a lot of the most famous women were given opportunities to write books. Martha Reeves, Mary Wilson from The Supremes, Ronnie Spector, obviously, Darlene Love. And it was interesting seeing how their perspectives had changed from now speaking to all of these people again versus what they had written at the time. For example, Mary Wilson, when her book about The Supremes came out. The review said things like, “You’ll never look at Diana Ross in the same way again.”

Well, yeah, there are great stories about Diana Ross and going into the wardrobe, but maybe you can tell one of those later. Go ahead.

Flam: All kinds of things like that, but also, her perspective on Motown at the time in the early ‘80s was very different than it’s now. Motown closed their doors very abruptly without telling a lot of their artists and Martha Reeves, for example, was kicked to the curb. Mary Wilson continued on with The Supremes for years and years and years, but her feeling was that both of them had not received nearly the money that they deserved. The contracts. There were a lot of conflicts of interest, especially with Motown early on. So when we got around to talking to a lot of these artists, those were a lot of the questions that we asked because we’d read all these firsthand perspectives of, “This is how we got treated at Motown.” “This is how I got screwed by Berry Gordy.”

So we asked Mary Wilson and Martha Reeves about it, and their perspectives actually had totally changed and were very different. Motown is such a storied entity, and things have changed legally since the ‘80s too, and people may be a lot happier with things that they have now that they didn’t have then, who knows as well. Also, in their 70s and 80s, which is the ages of pretty much everyone we spoke to, their life perspectives had changed about a lot of that. A lot of the women felt like they ended up making this impact in the world that was completely unfathomable to them at the time, and is still now a trip to walk into a store and hear your music playing or have someone come up and say, “I fell in love to your music.”

Jackie Hicks of The Andantes says, “There’s not a day goes by that I don’t hear my voice on the radio.”

Flam: Absolutely, and all of this thing, the great times, the hard times that music has gotten people through and what it conjures up in people and how it brings people together and is really the ultimate equalizer in so many ways, and these women were chosen for whatever reason, to be the voices of these songs that mean so much to so many people, and it’s such a powerful experience that it is humbling. So in terms of “are people bitter?” the women, I’d say across the board, they felt like they deserve more recognition for their contributions, at least artistically and across the board. Nobody was paid well enough. In general, the people that we spoke to, there was not a feeling of bitterness. Life is so long, and that was one of the perspectives that we really got from working on this project with so many people who are in their 70s and 80s and 90s. Mike Stoller is far into his 90s. I believe he was 95 when we spoke to him, I think.

I can’t believe he’s still around.

Flam: This was a blip in a long lifetime of love and heartache and children and houses and jobs and so many things, and it was a couple of years early on in teenage life. So while we see The Marvelettes and the members of The Marvelettes, we think, “Oh, ‘Please, Mr. Postman,’ this song, it’s so important to us.” That’s one part of a long life of so much. So that was a humbling experience, I felt working on it was just the feeling that in the end, all of these people that we’re speaking to us who are so far along in life, in the end, you kind of just have to play it as it lays and it’s all good, which it sounds cheesy, but in the end, you can choose to focus on being angry about things or you can’t. I would say that this is a group of women who chose not to focus on that, but instead to focus on the impact that they’ve had on people’s lives and how much joy they’ve brought to people.

You can’t take it with you. You can’t take money with you but you can leave that influence and impact.

Flam: Everybody would’ve been happy and it would be nice. Absolutely, but yes, in the end, what would be carved on people’s gravestones would not be about being screwed over by the music industry, any of these women, for sure.

How does the girl group era come to an end? I think that this may sound like an obvious question. Rock and roll happened and tastes change, and people grew up but certainly, some of them, Diana Ross, Patti LaBelle, Martha Reeves, they had gigantic solo careers. So it wasn’t a death knell for all of them. It was the girl group specifically that faded away. Why?

Sieu Liebowitz: Yes, there are a few reasons, and some are very obvious. The British invasion. What that did to the girl groups isn’t just kicking American artists off the charts. It’s not just displacing specifically Black music that had created rock and roll and R&B with white musicians who now mimicked that sound. As much as I love those musicians as well, that’s what happened and that’s not just that, but because of that, it really displaced women as a whole in the American structure. It really displaces the music structure. So the girl groups at that point, were not writing their own songs, so they cannot continue as songwriters.

And they are not launching solo careers or meant to launch solo careers. They’re based in vocal harmony. That just begins to dismantle as the music industry starts specifically, looking for the British invasion, towards the British invasion for the pop records and then, the people who are able to stand up to that are going to be the solo stars that mostly come out of Motown. Though the Motown groups were girl groups, they were also being groomed to continue as women. And that is done in a very specific way with etiquette school and charm school and also performance school, vocal coaches.

Flam: And even the clothes they wore, the Supremes were wearing gowns, not Bram dresses.

Sieu Liebowitz: You have those aspects and then, another aspect that I think is really important is the group that does seem to make it the most, right? The Supremes, the music subject changes but simultaneously, they also get an enormous amount of television time because the technology had changed and even though TV existed for the girl groups, America wasn’t open to seeing Black women on TV the same way. The Shirelles were not allowed on Ed Sullivan, even though they were as big, if not bigger, than the early Supremes when they were on Ed Sullivan, which is really what introduces them to a huge national audience. So I think that we also have to look at the way that technology and pop culture is changing around them. And then, America is changing. It’s not a time of innocence, it’s a time, rejecting that innocence of the naivete. We see that, buy ’68 we’ve seen three national assassinations in this country. Four.

It was RFK, MLK, JFK …

Sieu Liebowitz: And Malcolm X. And these are huge blows to what the girl groups really did culturally, which is this really strange amalgamation of … introducing, like Laura said, Black musicians to white audiences that wouldn’t traditionally have been open to it. It’s not necessarily those adjacent communities. It’s very disparate, different communities that kind of fine camaraderie in the girl group, pop sound. So, all of culture shifts around that. For a lot of the people in the girl groups, because they were young. At the time, it was a really difficult transition to make. So then the groups that do transition are either groomed for it by managers, frankly or you see something like Patti LaBelle and the Blue Belles who just truly reinvent themselves and seem to find themselves almost in this new moment.

Yeah, they become a LaBelle.

Flam: I mean, ultimately, it is a cyclical thing too. This generation that we are focusing on the book come up as teenagers. They have their own problems. They have their own issues, and they find music that they relate to of people with the same problem, singing about the same stuff. The ‘60s was such a time of all of the decades of change in our country, that 1962 and 1968, they definitely don’t look like they’re happening in the same decade.

Or the same planet.

Flam: Yeah, it’s hard to imagine something becoming so obsolete so fast. As I would say, the idea of innocence and your sweetheart and all of this stuff became to the generation that went to Vietnam and all of the movements, feminism, Black power, the same way that teenagers, the teenagers that we write about in our book, came about and had someone speak to them. When people continued on with their voices speaking for their next generation, they were singing about totally different stuff. They were worried about dying in the war. They were worried about completely different things than the teenager in 1958 or 1959 was. And they saw The Beatles on Ed Sullivan and they went out and they learned how to play guitar and drums.

And a generation of young, mostly men went out after seeing the Beatles on Ed Sullivan and did that and started expressing themselves through forming bands and writing their own material and obviously, this is very simplistic, but it is a huge thing that did happen. When the same way that all these professional songwriters had been gathered to write all of these songs to encapsulate their generation, the people who came after them were the opposite. They were writing for themselves about their own stuff and things just continued on from there and here we are now, but every generation of young people will ultimately age out quickly and then, a new generation that they feel like they totally don’t even relate to will show up with totally different things to sing about, and it’s what happened to them too.

I’ve got teens. That’s how I feel.

Liebowitz: I just wanted to piggyback on something Laura said because I think what’s really interesting, we try to talk about the technology in society and means of production in our book, but Phil Spector does weather that storm. Berry Gordy does weather that storm, and they do that by transitioning to different people. So I think that there’s something that is important also about the artist’s role often in culture and how disposable that can become, as opposed to the people who maybe are controlling more of those productions and have money to invest in other people making things that they no longer have their fingers on the pulse of.

Flam: A lot of the people that we spoke to in the book was beyond the female artists that we spoke to. Carole King went on to have an incredible career. Did very different stuff than the stuff that she wrote about in the late ‘50s and early ‘60s.

Liebowitz: She wrote the music for the Care Bear movies.

I don’t think I knew that.

Liebowitz: So that was very formative experience for me. Laura brings up the great point of what does happen with the songwriters that we do see having financial successes. They actually go [on to be] popular. So the girl group sound we say is one of the first true pop sounds. Judy Craig of the Chiffons is the one who introduced us to that idea and we definitely agree, and what happens is the songwriters who no longer can write music for the people buying Beatles records, they are instead writing Saturday morning cartoons and they’re instead writing jingles and they still are huge parts of our culture.

Joe Raposo over at Sesame Street.

Liebowitz: Yeah, so it’s like they carry on in these ways that then we don’t even see, but what is it Laura? How many soundtracks did Jeff Barry write or the intros for TV shows did Jeff Barry write?

Flam: Well, yeah, Jeff Barry, he and his wife, Ellie Greenwich, wrote so many of the girl group songs and the two of them wrote, I’d say hands down the most amount of girl group hits “Be My Baby,” “Chapel of Love.” Songs like that. He went on to write “Sugar, Sugar” and then, he did the theme for “The Jeffersons,” the theme for “One Day at a Time,” “Family Ties,” FGG [Feldman, Goldstein and Gottehrer] who wrote “My Boyfriend’s Back” that we speak to in the book, they went on to discover The Go-Go’s and found Sire Records and The Orchard and go on to do so many incredible things.

So while so many of the producers and songwriters, it was this launchpad to the rest of their lives, the artists just didn’t get to experience that and didn’t get to continue on in the same evolution as a lot of the other guys who got absorbed into the record biz did.

I feel like the art of the TV sitcom theme song, it’s dead.

Flam: I know. It’s so sad.

That’s too bad. Moment of silence for the TV sitcom theme. I know.

Flam: When we were talking to Jeff Barry, we quoted something back to him, he said, he said, “How do you remember that? As if it’s not just in our DNA?”

Imprinted in our brains. Yeah. “Family Ties.” My God. All right, so we’ve covered a lot of ground. I thought that was a lot of fun and there is a Spotify playlist. It’s just the name of the book, right? “But Will You Love Me Tomorrow”?

Flam: Actually that is one thing I would like to say in terms of choosing the title for the book. We love the song and The Shirelles, but the song is called “Will You Love Me Tomorrow?” Very often mistaken for “Will You Still Love Me Tomorrow?” So we thought about calling the book, “Will You Still Love Me Tomorrow?” But then it would be the inaccurate title of the song.

And it’s perfect because it’s like, do we love them tomorrow? And clearly you do, and hopefully a new generation will as well.

Flam: New generations always will. As Greil Marcus said, he once listened to that song for nine hours straight and it just kept getting better.

Check out this episode of “Brooklyn Magazine: The Podcast” for more. Subscribe and listen wherever you get your podcasts.

You might also like