Three Filmmakers On How They Tell Their Stories

Another day, another new series to binge or film to see. As Netflix, Amazon and HBO re-define how we watch TV and MoviePass upends the film industry, it’s clear we’re looking for more and more stories: from summer blockbusters to updated beloved classics to expansive mini-series to powerful documentaries and biopics. To understand why we’re so drawn to film, we asked a few of Brooklyn-based filmmakers for their thoughts on the power of storytelling and the magic of film.

Frank Ruy, Documentary Filmmaker & Screenwriter

Frank Ruy found the subject of his latest project at a storytelling workshop. He was invited to a special program initiated by The Yard, a coworking space where Ruy has his office in Williamsburg, and led by Dawn J. Fraser, Lead Instructor at The Moth. Over the course of a few days, Ruy’s eyes were opened to the art of live storytelling performances, which may look on the surface like stand-up comedy, but which he describes as “less defined – with more heart and impact. It’s a soup of vulnerability and empathy.” During the final showcase at The Yard, he met another storyteller, Sandi Marx, who has become the subject of his latest documentary project.

What was your background before beginning your newest project?

I worked at ABC News in the mid-90s but decided to leave that world and attend the NYU Graduate Film program in 2003. My first feature documentary, Giving It Up, was about the paparazzi and also served as my thesis film. I moved to LA and started following the paparazzi. While out there, I started hanging out with these guys. A lot of them were former gang members who got into the paparazzi business. It was a crazy time, before everyone had a cell phone with video that could record anyone around them. I got to see the two-way nature of the celebrity business and the economies of that world.

Can you tell us about your current work?

I feel really lucky to have found this subject matter: storytelling and Sandi. To be doing a film about the process and art of storytelling lets me reflect a little bit on my own work. Sandi Marx was in show business; she had a big talent agency in the 80s. Now she’s a professional, well-known storyteller. She has this almost double life. On one hand she’s a comfortable suburban retiree. But she also has this dangerous energy of a performer; it’s kind of a bohemian hipster thing. She’s going all over the city and getting on stage. She also has Lupus, which really affects everything, especially her energy. There’s a real duality to her, between these very quiet moments at home where she’s dealing with that and then really demonstrative performances. This storytelling doc is something that I think is timely right now. I think storytelling is having a moment as a response to the lack of empathy and listening we’re confronted with every day [these days].

What are the challenges of filming live storytelling as a stage performance?

I looked at concert documentary strategies, trying to find images that a live audience doesn’t get to see. But it’s hard, you obviously can’t get her to walk out on stage again just because the light isn’t right. You have to be flexible. By contrast, when she’s at home, I can be much more relaxed and the shot is more composed. It’s nice because the visual language has a relationship with the content and when you put two images next to one another, meanings start to appear. It becomes percussive.

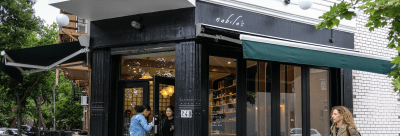

Caitlin Boyle, Executive Director of Film Sprout

With a background in radio and tv journalism, Caitlin Boyle started Film Sprout in 2009. In an office at The Yard in Gowanus, the boutique distribution firm works with documentary filmmakers, film distributors, NGOs and brands to create far-reaching social impact campaigns, produce marketing collateral and collaborate with grassroots organizations working for social change. With more than 40 projects spanning the last ten years, Film Sprout has engineered distribution campaigns covering a range of social issues, from second-chance employment for formerly incarcerated individuals in Cleveland to conservationist efforts in the mountains of British Columbia.

What stories do you find yourself drawn to when considering work for Film Sprout?

We have a double bottom line at Film Sprout: we want to do well by doing good. Of course, we want to represent films that have the potential to earn revenue in the marketplace. But there’s also a social transaction we’re looking to create value around. We want stories that are enriching not just financially but also on a deeply human level–that tap into the reservoirs of passion and emotion that each of us has as a film viewer. The best films pack an emotional gut punch that either implicitly or explicitly implicates the viewer, and compels them to care about the story. Audiences are hungry for stories with meaning, and at Film Sprout we can close the gap between the filmmakers telling these stories and the audiences who want to hear them.

How is your relationship with the audience different, given that these projects are defined as “social-impact films”?

We aim for different goals depending on the film. Some films offer a very precise consumer or civic call-to-action, others offer a means to understand new legislation or the need for policy change, others seek to cultivate a new awareness among viewers. Currently, we’re working on a film called The Judge, which disrupts stereotypes about Muslim women and women’s leadership, for example. Another film, releasing this summer, is called The Bleeding Edge and is about the FDA’s failure to appropriately test and regulate medical devices, like pacemakers, IUDs and hip replacements. The idea in every case is for the film to catalyze action: to perhaps wake up and rally those who have not yet been made aware of the issue, and, often even more powerfully— to offer an organizing tool for those advocates and stakeholders already working on the issue.

Considering you started in radio journalism, what’s special about storytelling through film?

Films have that visceral, powerfully immersive quality. When you’re watching a film in a public setting, you’re in the dark, and for a little while, you’re physically enveloped in that story; you’re not doing anything else. And then there’s a power to the communal element. We still watch films in public, together! We don’t gather around and listen to the radio together anymore (maybe we should!) But with film screenings, we still gather together in real time, in brick-and-mortar settings. Film screenings serve that fundamental stories-around-the-campfire impulse we all crave and need.

Travis Gorzelsky, Director & Editor

Travis Gorzelsky first fell in love with film from picking up an old VHS camera when he was 10 years old. After studying cinema and digital arts, he’s now a director/editor/cinematographer hired by brands such as Esquire, ELLE and NPR to work on a wide range of web editorials and series.

What are some of the differences in working for the internet compared with a feature or even short film?

Really, it’s the rhythm and the pacing. Seven minutes is a long video for the internet! You’re subject to the power of the audience. They can just scroll past it or turn it off. Right now, I’m working on a Snapchat series about basketball players called “Hype School for Overtime.” It’s a comedy. It’s very graphics heavy– no shot is more than a second. And you know that some kid is going to be watching it from his phone.

How does that kind of work compare with some of your documentary projects?

I love doing comedy, but it’s obviously nice to have a balance. To be telling a story that needs to be told, to have a little more time to show things and to make sure you get them right. I don’t want to say that it’s tough but you spend so much time with all the footage, so it affects you. It sounds maybe a bit much but it’s an honor to work on some of these stories. It’s storytelling that’s not contrived. You follow the lead and push the storylines into its most honest and best version.

Finally, what’s your approach to a project like the behind-the-scenes of your Swan Lake video?

For something like the Swan Lake piece, it’s about the music structure. I used to play music so that’s natural for me. Finding the right music was really important. Then it’s a little bit intuitive to try and translate the feeling of the music with the visuals. It’s about tapping into emotions.

You might also like