Illustration courtesy USG Audio

The life and legacy of Ol’ Dirty Bastard

Twenty years after his death, the iconic rapper is the subject of a new podcast that seeks to understand him

Like what you’re hearing? Subscribe to us at iTunes, check us out on Spotify and hear us on Google, Amazon, Stitcher and TuneIn. This is our RSS feed. Tell a friend!

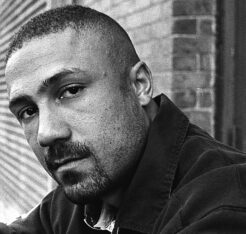

Khalik Allah

Russell Tyrone Jones was born in Fort Greene, Brooklyn, in 1968 and would go on to be known by many names — and many things — in his short 35 years. You are undoubtedly familiar with him as Ol’ Dirty Bastard, a founding member of the Wu Tang Clan and one of hip hop’s most explosive and complex characters.

He was a showman, a raw performer, a stage crasher, a comedian, a father, a husband, a literal hero, a son unique. He was also flawed. ODB struggled with addiction, had real run-ins with the law and grappled with mental health issues. But was was in no way, as the media often portrayed him, a caricature.

A new podcast, hosted by photographer and filmmaker Khalik Allah, seeks to strip away the bombastic persona and paint a more nuanced profile of the man. Over eight episodes, “ODB: A Son Unique“ unpacks the origins and impact of Ol’ Dirty Bastard, his influences — not the least of which was the Five-Percent Nation, an offshoot of the Nation of Islam — his style and the indelible mark he left on hip-hop through interviews with the people closest to him.

Allah is this week’s guest on “Brooklyn Magazine: The Podcast” to talk about the podcast and about one of Brooklyn’s more prominent native sons of the past few decades. ODB died in 2004, 20 years ago next year. But he still entertains and thrills us today. Wu-Tang, after all, is for the children.

The following is a transcript of our conversation, which airs as an episode of “Brooklyn Magazine: The Podcast,” edited for clarity. Listen in the player above or wherever you get your podcasts.

The idea of ODB is that he was just this wild persona, but he was, at least at first, a character played by Russell Jones. Listening to your podcast, you walk away with the perception that he was widely misunderstood. There was a lot of method behind the madness, at least at the very beginning. Can we talk about intention versus chaos? He’s got this chaotic public persona, but there was a lot of intention behind it.

ODB, man, was like a brilliant star. He was a sun. He shined his light, and he was an entertainer. I think it really goes back to the type of family member he was to his family, where they were a very musical family. They would sing soul songs. They would all entertain each other. They had a very close-knit, tight-knit bond with one another, and that’s why we have RZA being a genius and a mastermind. That’s why we have people like Popa Wu, The Genius as well.

RZA and The Genius were literal family members. They’re cousins.

And ODB as well. They’re all cousins.

You talked about growing up. I’m glad you did because I was going to get there a little later, but we can start there. He was born in Fort Greene in 1968. Obviously, this is a very different Fort Greene than we have here in 2023. You paint almost an idyllic picture of his childhood, growing up surrounded by family. What was he like?

I know more about ODB by way of Popa Wu, who was his older cousin. The thing is those brothers grew up with a serious level of discipline, especially in terms of the mathematics that they studied. That was the foundation for everything. The brothers came up in the Five-Percent Nation, which is considered an offshoot of the Nation of Islam. But what that gave brothers is what we call knowledge of self, and that’s knowing who you are as a person historically in America as a Black man. Most of our knowledge has been stripped away and hidden from us, so the Five-Percent Nation gives you a foundation in terms of world history, your contribution to history, and also a boost of self-esteem, a boost of self-knowledge and awareness which empowers you.

This is why they all call each other “God.” “The Black man is God,” and they refer to each other as God, young God. That’s all part of the Five-Percent ideology. I think I first heard the term associated with Afrika Bambaataa back in the day. But tell me more about this knowledge of self and self-esteem. That enters the picture through Popa Wu, the older cousin who was sort of the spiritual advisor. How does this come into the fray? Because it really is important to understanding who ODB is.

Oh, totally, man. It’s the foundation behind everything. It’s what gave brothers the magnetism, the discipline, the self-esteem, the consciousness. Ultimately, the Five Percenters are really responsible for hip hop, for injecting hip hop with knowledge. When we go back in the day, the emcees like Rakim, Big Daddy Kane, who were ODB’s predecessors, these were people who were strongly connected to the Five-Percent Nation. They were Five Percenters.

ODB, man, the music was an expression. When you have knowledge of self and you recognize yourself as God, you live your life to the fullest without really caring about other people’s judgment. Of course, the “Ol’ Dirty Bastard” was his persona. His proper name was Ason Unique Allah as a Five Percenter, as a God. But the brother was himself. He was a wild brother from Brooklyn. That was really who he was.

He was watching kung fu flicks with RZA and seeing a character called Dirty Ho and was just like, “Yo, I’m the Ol’ Dirty Bastard,” and the brothers encouraged that. That’s who you are. That’s who he was because like they say in “36 Chambers,” “There’s no father to his style.” He had an unorthodox approach to emceeing and, before anything, the Five Percenters teach to be original. Back in the day of hip hop, there were no clones. Everybody had an original contribution to give to the game, and the brother definitely lived that out.

You’re hitting on a lot of things that I wanted to ask about right out the gate, which is awesome. The name, Ol’ Dirty Bastard, he and his cousins grew up watching kung fu movies. But I got the impression that even for some of them, they’re like, “Ol Dirty Bastard’s a little bit crazy,” even for the Five-Percent mindset. Talk about that. He’s almost flipping it a little bit.

His Five Percenter attribute, Ason Unique, touches on that, too. He was definitely a unique thinker, a unique personality. I like to say he was like a shooting star. He couldn’t be stopped. He couldn’t be contained. When I look at him personally, my view was that he was extremely spiritual in the sense that there wasn’t any limitations to his self-expression. It’s like the light just shines, and it sometimes shines through things and it doesn’t really give a fuck about being stopped. It’s just as itself, like the sun. That’s what I get from him.

Me personally, I look at him as a fearless individual. He was fearless. He was extremely courageous. We see that in ’98 when he stormed the Grammy stage.

I want to get to that, for sure. You yourself are a Five Percenter. You’re a filmmaker, photographer, now podcaster. You have personal ties to Wu-Tang. You were their photographer. Your first feature from 2010 was about Popa Wu. Did you know ODB personally?

No. I met ODB a couple of times at the Universal Parliament of the Five Percenters uptown in Harlem. Also, I met him back in the day in Brooklyn, but that was at Fort Greene Park. But we never really broke bread and chopped it up. I was very close with his older cousin, Popa Wu, Freedom Allah.

Originally, man, I was just a fan of the music. I’m a lot younger than them. When I was 12 years old in 1997, “Wu-Tang Forever” came out. Of course, I was familiar with “36 Chambers.” But when “Wu-Tang Forever” came out and the first track was a cut called “Wu-Revolution” and it’s just Popa Wu just speaking. He’s just almost preaching on that track. That captivated me. This was two years before I got knowledge of self and became a student enrolled in the curriculum of the Five-Percent Nation.

And then when I met him at the Parliament, the rallies used to be held in Fort Greene Park at the top of the hill. We just had a brotherhood immediately. So later on, there were other brothers I met, like Masta Killa, and this was just all through knowledge of self. It wasn’t really at hip hop shows or nothing like that. But Popa Wu would later on take me into the studio when brothers were recording. But unfortunately, this was after 2004, so it was after ODB had already returned, after he already had passed away.

His output, by the time he did pass, it wasn’t exactly prolific, but the impact was tremendous due to his talent, his public antics, his legal troubles. He became a folk hero. How do you see his legacy? If someone was just beamed down from outer space and landed in Brooklyn, what do you tell them about who Ol’ Dirty Bastard was?

He’s almost an indescribable character. But I would just say he’s a man who lived by his own rules. He was under no rules but God, which is his own. This is a person that was totally free and was full of love. He loved so many people, and he gave his love freely. He saved a little girl’s life. We describe that in the podcast. This is a person that was joyous despite growing up in poverty. This is somebody who was extremely rich, not just with money, but I mean rich with love, rich with happiness, rich with talent.

This is a brother who was a beacon of light to many people, who encouraged many people. When we talk about Wu-Tang itself, Raekwon goes on to say that ODB was the source of confidence for the group. He was the type like, “Yo, we’re going to go in here and represent, and nobody’s going to stop us.” I feel like his courage was infectious. His confidence was infectious.

He was also the type of emcee that didn’t care about being so lyrical. He was more or less so confident behind what he was saying, that you just felt them. He was the type of emcee that you would feel, which is characteristic of an old school emcee. You feel him. That’s what I got from the brother.

Talk about how rapping, for him, entered the picture. He was obviously in this very talented family, had these very brilliant cousins. Before Wu-Tang, there was Force of the Imperial Master, which became known as All in Together Now, all informed by Five-Percent. What did rapping represent to Russell, to Ason? Was it a vehicle for fame or communication, for connection? Obviously, he had this insane charisma out the gate. How did it come to him, and what did it mean to him?

I think it was all of that. I think that the brother definitely wanted to be in the limelight. He recognized that he had a distinct style and a unique contribution to add to hip hop, and also he was out for the paper. He wanted to be paid. Wu-Tang wanted to be paid. I would say him and RZA masterminded the entire thing in terms of understanding that they were going to be big and having absolutely no doubt about that.

He definitely just understood, “Nobody could fuck with me.” He had that type of mentality, where it was like, “Yo, we going to come in the game and smash it.” That type of confidence is what led Wu-Tang to be what it is and to be such a powerful, bright light in hip hop and what I would consider the best group in hip hop history ever.

“Enter the Wu-Tang (36 Chambers)” comes out in 1993. Wu-Tang debuted. He absolutely explodes off the record whenever he shows up. As you said, no father to his style. How do you describe his style? You sort of did a little bit.

His style was original to the fullest, electric, confident, harmonious. The brother would sing, too. He had such a harmony behind his verses. When you hear him on “C.R.E.A.M.,” that’s him and another family member called 60 Second Assassin that are harmonizing throughout that, as well as Buddha Monk. He blended many styles. He blended his love for soul music. He brought that into his emceeing. Rugged as hell, really street, really street, really Brooklyn. He epitomized Brooklyn back in the ’70, ’80s, and ’90s. He represented the streets and the struggle. His style was a blend of all of that, all of the influences of New York City.

You mentioned RZA being very deliberate about their careers, which he did. They did their solo albums on different labels. There was the idea to spread it around, make the money. And then he does his solo album, “Return to the 36 Chambers,” in 1995, huge year for him. He collaborates with Mariah Carey on her remix for “Fantasy.” Talk about what that collaboration represented.

I think that that just represented the mass appeal that Wu-Tang had. ODB being the antithesis to Mariah Carey, them just coming together and making a smash hit just represented another breakthrough for hip hop culture. We’ve seen these breakthroughs multiple times with Aerosmith and Run-DMC collaborating, and then we also see it with Ol’ Dirty Bastard and Mariah Carey. It’s like a man who calls himself dirty up against somebody so clean.

The cleanest woman imaginable. Yeah.

[Laughs.] To me, it represented unity. It also represented another breakthrough in hip hop culture. After that, you had so many duplicates. You had so many copycats. You had so many R&B singers reaching out to rugged hip hop artists to get them on the record to feature them. But Ol’ Dirty Bastard, man, he was the first to do a lot of things.

That first solo album, too, was huge. I mean “Shimmy Shimmy Ya.” “Brooklyn Zoo.” You get into the making of the cover, which is his welfare card, which brings me to another chapter in your podcast. You talked to Touré. He’s actually a Fort Greener. He’s been on this podcast, super interesting guy, impactful journalist in his own right. But he was the guy who was at MTV and was essentially behind the segment where ODB took two of his kids in a limousine to cash a welfare check and receive food stamps. It was a stunt. It was perfect for publicity. It had a message behind it, but I think that message ended up not having the consequences maybe that ODB probably intended from the … Talk about that moment where he rolls up in a limo to get food stamps. What was he thinking, and where did that turn on him?

I mean my interpretation of that is that he was saying to the world, to his fans, to the government that he is now the representative of where he came from. He, in a sense, is the political leader of the hood, of the streets, and that although he became famous and a superstar, he’s in no way detached from the roots from which he sprang. So really, that’s what I see him doing, saying like, “Yo, okay, get this money. Get this free money any way you can.”

Was it a comment on the recording industry itself in terms of not getting paid what he was due, or was it just strictly to connect with the streets?

When you’re a Black man in America and you understand that 400 years of free slave labor, 400-plus years, built this country and made this a world power, we never got that 40 acres and a mule. We never got proper reparations at all, and we’re still considered second class citizens in this country. So I think all this, just having the knowledge of self, having that Five Percenter understanding and that foundation is like, “Yo, I may be doing well, but my people are suffering. Fuck it. If I could get some welfare, I’m going to get it, and you should get it, too.” Ultimately, that’s what I believe the message to be. Nobody really knows, except him. That’s my interpretation.

But then, of course, it gets presented by critics of welfare as representative of widespread fraud and abuse.

Of course, that’s the way that they’re going to spin it because nobody wants Black people to have anything anyway. So it’s like, “All right, okay, fuck it. This guy’s misusing the system.” Meanwhile, he’s been at the mercy of the system. Ol’ Dirty Bastard is also Shinnecock Indian. Popa Wu used to ask him to drive him to the reservation in Long Island, the Shinnecock Reservation, because they have that in them as well.

So when you combine American slavery with the massacre of the Native American population, it just is like, “Damn. All right, I’m going to just take this little crumb of welfare anyway. Fuck it.”

You mentioned the Grammys. You actually start your podcast at the Grammys in 1998. He crashes the stage when Wu-Tang doesn’t win, and he shouts that “Wu-Tang is for the children,” among other things. This was in the middle of three consecutive incredible days in his life. The day before is when he witnessed the car accident that you mentioned. I’ll let you describe what happened. But basically, a young girl was pinned under a car, and here he is, a superstar, comes out, shocks everyone around him, and takes control of the situation. Talk about that moment, and that was the day before the Grammys.

The young woman’s name is Maati Lovell. She was four years old at the time, and this podcast afforded me the ability to meet her. I always heard the story.

It’s like a legend.

Yeah, yeah, yeah. Like an urban legend kind of thing. I always heard about it, but then to actually meet the person and meet her mother was deep. But yeah, this car was speeding, and it struck Maati. She was underneath it, and ODB came and lifted it up, not just by himself, but with the brothers that he was with. He was with a handful of brothers on the corner, and he was the one who witnessed it, mustered the brothers together to come through and to lift the car off of her.

That’s just the testimony to the type of heart that he had, the type of care and empathy and compassion and willingness to save life, to preserve life when he saw something like that. That phrase that Wu-Tang always speaks about, “Wu-Tang is for the children,” it’s a play on what the Gods say. The babies are the greatest. So it’s more or less like we’re about teaching the next generation the real importance of life and developing their morals, developing them a level of self-respect and integrity, and Wu-Tang did that through their music.

When Wu-Tang put out “36 Chambers” and following up with “Wu-Tang Forever,” it was somewhat indisputable in the streets of New York, and probably across the country, that this is the best hip hop going right now, so to go to the Grammys and not to get —

In his new clothes.

In his new clothes, which he’d paid $1,500 for that, and he got his braids done and he was fresh to death. It was like, “Yo, what do you mean we didn’t win? What? What? Puffy is good, but Wu-Tang is for the children. Wu-Tang is the best.” Maybe the industry didn’t feel them, but the streets felt them. That’s how the streets felt. Hip hop originally is a form of art from the street, from the curb. So it’s like we don’t give a fuck what the industry is saying. ODB being just a brother from the hood, from the streets, was speaking up and almost reclaiming hip hop. We see it go in this corporate direction, but that’s not where it belongs. It came from this, so I need to speak up. I need to do something.

This was the day after he saves the girl. I mean he’s walking the walk. It’s clearly like he’s not just full of bravado. If you were in a moment of crisis, it shows you who you are as a person, and he is for the children. But obviously, his antics on stage of the Grammys were fodder for the media, painted him in a certain way. It was a very intentional choice of yours to start your podcast, I would imagine, at this precise moment. Talk about that decision.

I have to thank my producer and just the whole team. Look, I’m not a podcaster. I’m a filmmaker. But in some ways, this is similar to that. My man, Tayler, who produces. But they approached me, man, and Veronica Simmons as well was just like, “Perhaps this would be something that you would like to do.” I said, “Let me consider it.” And then I’m like, “Let me do this just out of respect and praises for the God, Ason Unique.”

Me and Taylor worked through the episodes together. The final editing was done by Novel as well. But I do believe that that’s a great place to start. I’m glad that we started it off like that because that’s a hook for the audience to get into the story because most people know about that. The day after, he was on The Howard Stern Show.

That’s what I was going to get to. Next is the third day in his three-day streak: he saves the girl, Grammys, Howard Stern, who conducts this gross interview. It’s very snide, and he handles it with grace.

Those three days, if Ol’ Dirty Bastard wasn’t a household name before that, those three days made him a household name. That’s why it was a great way to begin the podcast with that story and then to go beneath the surface, to go deeper afterwards, after release. Because it was 2004 that the brother passed away, so we’re looking at just about 20 years ago.

It’s crazy.

Similar to Tupac, similar to B.I.G, these people live on and their legacy lives on. There’s been many documentaries about Ol’ Dirty Bastard, about Wu-Tang in general, but this story is a more specific, nuanced story. I feel blessed to have been the one to host this podcast, and I’ve discovered a new talent.

The Howard Stern interview encapsulates how mainstream media interpreted him, portrayed him. Again, he handles it well. This doesn’t discount, though, he did have very real legal troubles. He was jailed in 2006. He was dumped by his record label. He was dumped by Elektra. He had priors, second degree assault, attempted robbery. He had been shot, arrested for wearing body armor. So this is not to say he was a saint. He was a complex individual. Obviously, the media, if it bleeds, it leads, and they’re going to go for the most scandalous. But talk about, if you can, about that side of ODB.

ODB was thorough. He was a brother from the streets. Brothers carried guns. Brothers protected themself. I don’t ever think that he was the antagonist or that he was out there looking for trouble, but felt as if he was a target. Being so well-known and you’re a celebrity, but you’re still keeping it in the hood, a lot comes with that. Most brothers just get as far away from possible from the streets once they get to a certain degree. He didn’t want to do that. He was still drinking 40s. Ol’ Dirty loved specific drugs. He loved them. That was just something that he did. A lot of brothers did, but I can’t sugarcoat that aspect of it. But I would say that he was a target and, if he was carrying heat, it was more for self-defense.

If you stick out your neck, you have to protect your neck.

You have to protect your neck. Protect your neck. Wu-Tang Clan is nothing to fuck with. So it’s like you’re not going to fuck with Ol’ Dirty Bastard. What do you expect? You don’t expect them to just get up and bounce to the Hollywood Hills. Some brothers did. Of course, there’s a Wu-Tang mansion out on the West Coast and all of that. But the brother kept it to the grain. There’s a saying that Wu-Tang would always say, don’t go against the grain. The brother kept it really straight hardwood all the time, and that’s just who he was, man. A lot comes with that. When you add money, when you become an object of perhaps jealousy or even his own paranoia could have attracted certain things.

He’s very much, in the end, I mean this is what leads to his ultimate downfall when he’s arrested in 2006, and that’s a very hard experience for him. People went out of their way, it seems like, to get him. He’s very much a victim of his own excesses, but he’s also a victim of the system.

He kept saying that the government was out to get him. That could be perceived as paranoia, but perhaps it was true. His mother speaks about he was never the same after going to jail and them drugging him up and injecting him with also some poisons.

Was there ever a confirmation that he was put on meds or what those meds were when he was in prison?

I’m forgetting the name right now of the exact medication he was given, but he was given multiple different things. People got to listen to the podcast.

I read a quote from the RZA about that time, and they said from the time they put him in jail, to all the drugs he was doing, to all the stress he went through with his family, “it took away his ability to see.”

That’s a comment on the jail system as well. The jail is not about rehabilitating anybody. They break you down, make your situation 10 times worse.

Do you have a sense of, not to play armchair psychiatrist or whatever, but are there bipolar attributes here? Is that at play? Is there some sort of mental health decline or was it drug use? He seemed, I guess, clouded towards the end. They talk about his final live performances being almost grotesque. What ultimately do you think went wrong?

I think that there’s a fine line between genius and insanity, and the brother was most definitely a genius. And yet, life in a way perhaps began breaking him down because he was away from his children. That could make anybody crack. He was locked up. He was away from all of the women that he loved. The brother loved women. Now he’s put in jail, and there’s no women around.

And he’s a target in jail, too.

He’s a target in jail. He’s being disrespected. You go from the heights of the hip hop game to the depths of hell. That could really affect a person, no matter what their psychological state is, no matter how healthy they are. That could create such a dissonance within one’s own mind and such a fracture in one’s own psychology, and I think that he went through that. He went through things that the average person will never go through because he was such a superstar. He was literally on a track with Pras, “Ghetto Supastar.” And then to have everything somewhat stripped away from you was like the biblical story of Job. The drugs definitely played a part as well. It’s just sad. It’s more complicated than even I could describe. Put it that way. I won’t even try to diagnose the situation, but I would just say it’s extremely complicated. Underneath all of that is a brilliant light and a very powerful thinker who, along with RZA and GZA, is responsible for giving birth to the greatest rap group in hip hop.

You yourself are interesting. Your career’s interesting. Your photography’s amazing. I was checking some of it out. Talk a little bit about your own background. I know your mother’s Jamaican. Your father’s Iranian. How was that mix for you growing up, and how does that inform your work?

I grew up here in New York, coming from two parents from totally different heritages and being the middle child. I got two older brothers, two younger brothers. I mean we really grew up b-boying, spinning on our head, doing windmills, doing graffiti. When I picked up the camera, it was just to depict the life that we had because when you see Larry Clark, “Kids,” when you see that film, that’s like how we were. We were those type of kids.

In some ways, even Popa Wu would tell me that I remind him of Ol’ Dirty Bastard because I was just wild, younger. I’m much more calm now and professional compared to how I used to be. The camera became an outlet for me. I consider myself a visual emcee. I was never able to rap good. You know what I’m saying? The camera became my form of expression in terms of filmmaking and photography.

I just love hip hop, man. I feel like I’ve developed my own voice in filmmaking. One of the main characters in my photography is a reoccurring character named Frenchie, and this man is a 63-year-old bipolar schizophrenic Haitian man. They call him Frenchie because he speaks Creole. The streets gave him that name. But some of the pictures that I’ve taken of him resembled the same spirit that we identify in Ol’ Dirty Bastard, that wild character, but that’s still happy, a profound mind.

I think I was drawn to this one person that I met in the streets because of that, because to me, he resembled the Ol’ Dirty Bastard. But yeah, man, as far as where I’m at, I’m continuing to work. I’m continuing to work in filmmaking. I’ll have a new film coming out within a year or so.

What’s that one about?

I’m working with A24. Another project in Jamaica. I made a film in Jamaica called “Black Mother.” It was on the Criterion channel. It was on various platforms, Channel 4 in the U.K., ARTE in France, and I’m just continuing to just stay focused on developing my eye because I’m 38 right now. These two years before hitting 40, I want to be meaningful. I want to continue studying and sharpening my tools. Filmmaking is a little bit different than hip hop. Whereas hip hop is such a young man’s sport, a lot of great filmmakers don’t start making their best work until even their 50s, some their 60s.

I think it was Kurosawa who said that when he was 80, he had just figured out how to make movies and he didn’t have any time left.

Exactly. That’s how it goes, man.

Check out this episode of “Brooklyn Magazine: The Podcast” for more. Subscribe and listen wherever you get your podcasts.

You might also like