"Gowanus Canal cleanup" by Zach K is licensed with CC BY-NC 2.0

BK Mag 311: A cheat sheet to the Gowanus rezoning kerfuffle

A brief explainer as Gowanus residents prepare to go to court over a proposed massive rezoning

Gowanus residents opposed to the proposed neighborhood rezoning will finally have their day in court on January 28. And they have one message for the city’s planners and developers: Not in my backyard, not in my neighborhood and definitely not anywhere near my sewage-ridden canal.

UPDATE: A Brooklyn Supreme Court judge partially lifted the temporary restraining order against the Gowanus rezoning Thursday, ordering the city to release its 80-block rezoning application to the public. In the meantime, all of the background in this explainer remains current as of Feb. 8.

Brooklyn Magazine attempts to break it all down:

What exactly is happening on January 28?

We’re glad you asked! On Thursday, representatives for the Voice of Gowanus coalition will face off against the Department of City Planning in a high-stakes legal hearing over the DCP’s plans to hold virtual public review meetings for phase one of its rezoning proposal.

Because the only thing more fun than a zoning meeting is a Zoom zoning meeting?

Right. Last week, a Brooklyn judge preliminarily sided with the Voice of Gowanus’ lawsuit that the DCP’s virtual meetings were not only inequitable, but “illegal,” and blocked the DCP’s plans to begin rezoning Gowanus on Jan. 19.

Now, the judge’s Thursday ruling will determine if city planners can formally begin rezoning Gowanus this month or if they will have to wait until Governor Andrew Cuomo lifts the pandemic-triggered state of emergency.

What is being proposed as part of the Gowanus rezoning?

The Gowanus Neighborhood Plan is a series of rezonings that will allow developers to construct mid- and high-rise buildings and thousands of apartments in Gowanus. The plan includes a project on the corner of Smith and Fifth streets, called Gowanus Green, which includes the construction of nearly a thousand affordable apartments, commercial spaces and parkland on a six-acre parcel of polluted land near the Gowanus Canal, known as Public Place.

Dumb question: What is a rezoning, anyway?

There are no dumb questions here! Rezoning is the process of designating a plot of land for a use other than that for which the land was originally intended. Simply put, zoning laws govern what can be built where. Zoning laws, for instance, could prevent the construction of a nuclear power plant next to an elementary school.

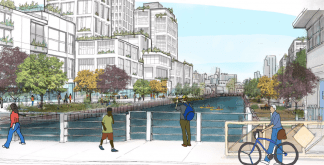

The proposed rezoning (courtesy nyc.gov)

If Public Place wasn’t originally designated to house apartments, what was its purpose?

News of the Gowanus rezoning seems to resurface in the local papers every couple of months, returning to the public consciousness like a mob victim resurfacing from the bowels of the canal’s murky, sludge-infested waters.

In 1974, Community Board 6 voted to reserve all six acres of Public Place—the site of developers’ Gowanus Green proposal—for “recreational use only,” according to a 1974 City Planning Commission document. Ideas for a Gowanus rezoning didn’t materialize until 2007, when the New York City Department of Housing and Preservation officially requested proposals to redevelop Public Place, which was formerly the site of a gas plant. The following year, Mayor Bloomberg’s administration awarded the Gowanus Green project to Hudson Companies, Jonathan Rose Companies, Fifth Avenue Committee and the Bluestone Organization.

But it wasn’t until 2010, when District 39 Councilman Brad Lander took office, that Gowanus became a real estate money grab tabula rasa for developers and a battle ground for hawkish NIMBYs concerned residents. During Lander’s tenure, the Gowanus Green project grew from a series of 12-story buildings along the Gowanus Canal to a proposal for 22-story to 30-story towers stretching an 80-block span, say Voice of Gowanus representatives.

What are the main arguments against the rezoning?

Emily Myers, a reporter for Brick Underground, says locals consider the word “rezoning” to be “shorthand for gentrification”—the single most hated buzzword in NYC parlance.

More specifically, Voice of Gowanus members worry that rezoning proposals neglect the need to allocate funds toward housing improvements benefitting existing Gowanus residents—4,300 of whom live in dilapidated NYCHA housing—and prioritize attracting wealthier, whiter out-of-towners instead.

Organizers also worry that a toxic chemical stew left behind by a former gas plant will affect the health and safety of Gowanus’ future residents.

The idea of those future residents is another sticking point for locals, though. They fear the roughly 20,000 people expected to flock to Gowanus after the completion of the neighborhood’s rezoning and construction proposals will overwhelm the neighborhood’s already-strained infrastructure (and sewage system).

Sounds pretty convincing. What are the arguments in support of the Gowanus Canal?

Brad Lander is vocal about how a Gowanus rezoning, and developer’s projects, will provide jobs during a pandemic-triggered recession that has currently left about 11 percent of NYC residents unemployed.

“The proposed Gowanus Neighborhood Rezoning is the first city-sponsored neighborhood rezoning in a whiter, wealthier community,” Lander co-wrote in a City Limits opinion piece last September. “It asks those residents to absorb new growth in order to create new, permanent affordability in a high-opportunity neighborhood with strong transit access.”

Ok, jobs and affordability are good things. But you keep saying things like “sewage,” “sludge” and “septic.” Isn’t the Gowanus Canal super toxic or something?

Toxic like a Britney hit. In 2010, the Environmental Protection Agency confirmed the presence of toxic coal tar, a known carcinogen, and “more than a dozen contaminants at high levels” in the canal’s sediments. What’s more, the canal’s real sediment lies beneath 10-feet of gooey, gelatinous black mayonnaise.

Black what?

Don’t take our word for it. “It just kind of oozes,” Gowanus Canal EPA Cleanup Manager Christos Tsiamis told the New York Times in 2010. “There is a stench associated with it. And it has the texture of thick mayonnaise, so it’s very unpleasant stuff. It’s a mixture of products, and a mixture always scares you because you don’t have a handle on it. You don’t know what it is.”

And as if that description of oozing guck weren’t enough to make your stomach churn, there’s more: Every year, 363 million gallons of raw sewage and polluted run-off run through the Gowanus Canal, according to the Gowanus Canal Conservancy.

Photo by MichaelTapp, licensed with CC BY-NC 2.0

Can’t we just clean it up or something?

In 2010, the Environmental Protection Agency designated the Gowanus Canal a Superfund site. As such, the canal will undergo a federally-supervised cleanup with a projected sticker price of $1.5 billion. National Grid and the City of New York, along with 28 other organizations charged with the pollution, will participate in the cleanup. The project—despite many delays—finally began in November 2020, and will continue through mid-2023.

During that time, officials will install two subterranean tanks to prevent sewage and street run-off from overflowing into the canal during storms. From there, the sewage will be transported to a waste management facility, where it will be treated. After the project’s completion, EPA officials will revisit the site every five years to ensure pollutants don’t resurface.

But according to Katia Kelly, a Brooklyn blogger who spoke with Spectrum News back in July, Combined Sewage Overflow, or CSOs, “might eventually sink and settle on top of the caps meant to keep black mayo from mingling in the canal waters and essentially undo [past] cleanups.”

Historian Joseph Alexiou, author of “Gowanus: Brooklyn’s Curious Canal,” doubts the Gowanus Canal, or the land surrounding it, will ever be truly clean: “Now, 158 years later, the city has not yet finished cleaning the Gowanus Canal. Chances are it never will,” he wrote in a Brooklyn Eagle op-ed last year.

In fact, just this week, a barge ship loaded with polluted sediment from the Gowanus Canal sank in the Gowanus Bay, the EPA said Monday.

So if the canal and the land surrounding it are so toxic, maybe we should just stop trying to make something there?

Depends on whom you ask!

You might also like