Illustration by Bridie Cheeseman

A Lebanese market thrives where a Polish grocer once served Greenpoint

Edy’s has been a rare feel-good pandemic success story. It’s also a parable about immigration and gentrification in Brooklyn

Edy’s stocked shelves

The corner of Meserole Avenue and Eckford Street in Greenpoint is not known for its foot traffic. Even though it’s just two short blocks from the bustle of the neighborhood’s main artery, Manhattan Avenue, the spot is quiet and residential, lined with apartment buildings of different colored bricks—red, brown, gray.

But by noon on a recent Sunday, despite some strong winds, a socially distanced lunch line begins to form down Meserole. The bundled customers shiver while waiting to get inside Edy’s Grocer, a new takeout eatery selling fresh takes on Lebanese cuisine and a variety of packaged Arab foods. By 12:30, the line stretches over a block.

Inside the small store, the neatly-stocked shelves hold an array of boutique Lebanese and other Middle Eastern items, from spices to packaged baklava to sesame seed cookies to jars of figs in sweet syrup. The fresh food display includes a large pot of chickpea and eggplant stew and a lemony chicken thigh dish. The color scheme, seen in everything from the menu blackboards to the tote bags and other merchandise for sale, is light pink, white and bright green.

Owner Edouard Massih, a long-limbed 26-year-old, toils behind the counter bringing platters back and forth from the kitchen hidden from view. “I’m always doing something,” he says.

Greenpointer Matt Megan, 28, sits with his friend Nathan Pastor, who biked over from Clinton Hill, just outside on a small bench painted green to match the store’s signage. They are eating two different kinds of man’oushe, a traditional Lebanese flatbread topped with spices, cheese and vegetables.

“I came here for the spices, originally,” Megan says, especially the za’atar. Pastor had read a mention of the store in the New Yorker.

Edy’s Grocer is one of Brooklyn’s rare pandemic success stories—a new small business that has won heaps of press coverage thanks to its owner’s ambition, quickly built up a loyal customer base with its quality food and positioned itself perfectly for the Covid quarantine era, selling takeout that is easy to take home and save, along with specialty goods that can’t be found in many places in northern Brooklyn.

It is also a perfect encapsulation of the transformation of Greenpoint, which used to be a gritty industrial zone populated with European immigrant workers—predominantly Polish over time—but is now a hyper-gentrified offshoot of neighboring Williamsburg, home to a wealthy creative class and a vibrant multicultural dining scene.

The store is itself the product of two immigrant stories: Massih, whose family left Lebanon for the U.S. when he was 10, inherited the space from a Polish immigrant named Maria Puk, who ran a small grocery store in the space for over four decades. Massih is keeping Puk’s legacy intact, with a large “Maria’s Deli” sign on a wall just to the right of the front door and some Polish-inspired options on his menu, including potato pancakes (from the local Polish Polka Dot deli) and homemade borscht. A photo on the glass food display case shows Massih posing with Puk and members of her family, everyone all smiles.

Some of Massih’s customers seem to appreciate the small local business’ backstory. Others are just intrigued by the food.

Towards the front of the line, two middle-aged men named Marios and Steve say they stumbled on Edy’s while walking not far from their longtime home in north Williamsburg. It was a welcome find, Steve says, in light of how Greenpoint has “completely changed” over the last decade, becoming “a lot more crowded.”

“Greenpoint is just five or 10 years behind [Williamsburg] in its gentrification,” adds Marios.

Further back in the queue outside is Alex Pirozzi, a new customer who has lived in the neighborhood for 20 years. She calls many of the businesses that have moved into the neighborhood, such as Starbucks and other chains, “charmless.”

“This is the opposite of that,” she says through a large pink scarf. “I love the story of their friendship, and I’m glad to be supporting a local business.”

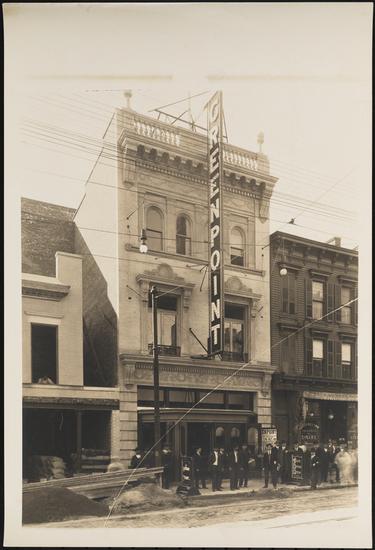

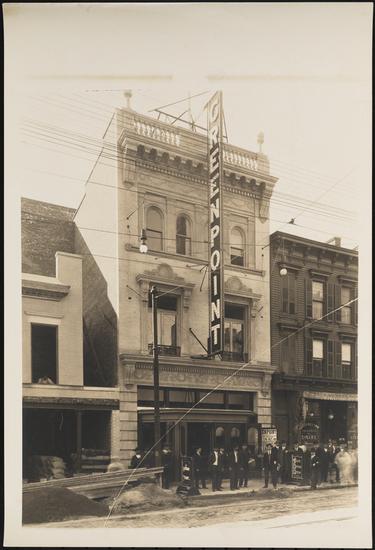

Wurts Bros., Manhattan Avenue, Greenpoint. RKO Theater, 1908, Museum of the City of New York, X2010.7.2.25806

Big changes in ‘Little Poland’

In the mid-19th century, Greenpoint wasn’t a place for trendy eateries. It was full of factories that manufactured everything from glass to furniture to shipbuilding materials. There were also dozens of oil refineries, sugar refineries and a brewery.

The workers who labored there—and in some cases lived there, sometimes in complexes built for them—were mainly German, Irish and Italian until the turn of the 20th century, when the neighborhood saw an increase in Polish immigrants. Over time, the non-Polish populations moved elsewhere throughout the borough. Italians, for instance, maintained a solid community on the other side of the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway, in Williamsburg. But the Polish remained, and most new Polish immigrants to New York flocked to the area, which began to blossom into a “Little Poland.”

“Their language was here. And the proverbial birds of the feather, right?” says Judith DeSena, a sociology professor at St. John’s University and longtime Greenpoint resident who has written about the history and gentrification of the area. “That’s really the story of immigration to the United States.”

But it wasn’t until a second wave of Polish immigration in the 1980s—as the anti-communist Solidarity Movement exploded in Poland and sparked a martial law clampdown—that the neighborhood became one of the most Polish in the United States, blanketed by Polish grocery stores, restaurants, bakeries and meat shops. A New York Times report from 1984 noted Greenpoint had become “more Polish than ever”: “[B]efore the latest influx, Greenpoint was like many other established immigrant communities. The second generation was becoming more American: old customs, even the Polish tongue itself, were fading away.”

That might sound like a familiar refrain. For more than a decade now, the same lament has been sounded about the neighborhood, as gentrification has pushed many of its Polish residents out. The median rent for a one bedroom Greenpoint apartment was $2,800 in 2018. DeSena says many have moved east to Queens neighborhoods such as Maspeth, Middle Village and Ridgewood. Others have gone back to Poland, where their money goes farther and their families may own larger properties.

Greenpoint benefited financially from its close location to both Manhattan and Williamsburg, becoming the hip little brother of the latter, with enough separation from the busy Bedford Avenue area to give its residents a sense of quiet coziness. Its food scene has been a good barometer of the influence of the newer non-Polish gentrifying forces. Prior to the pandemic, it was home to restaurants ranging from Cherry Point, which served “refined” British dishes and cocktails (before closing in April), to Chez Ma Tante, a quirky conglomeration of European influences, to Di and Di, which regularly had weeks-long waiting lists of people eager to try their chic Vietnamese offerings.

Maria Puk, who is 66, immigrated with her family in 1963, so she has seen the area’s full transformation. Not speaking English was at first an obstacle for all of them, who had moved to be near members of her father’s family. In her early years there, Puk said her neighbors were mostly Irish and German. But she said that by the ’90s, Polish was spoken in most stores.

Over time, the Polish community felt comfortable together as a tight cohort, impervious to the rest of contemporary Brooklyn culture.

“People used to sit outside til 2, 3 o’clock in the morning, having beers and hanging out by their houses,” she says.

Maria’s Deli was at first just a small grocery store selling staples such as butter, eggs, flour, milk and canned foods. As more people frequented the spot, she began serving sandwiches, sauerkraut, bagels, coffee and a variety of soups, from goulash to cabbage soup to borscht.

The pandemic decimated her business, but she is very happy for Massih, who went from a regular customer to an unlikely friend to something close to an “adopted son.” The two had talked about Massih taking over the space—having his own restaurant was always an ambition of his—before the Covid crisis, so Puk was happy to hand it off. She is now thoroughly enjoying her retirement, she says on the phone from a vacation in the Florida Keys.

“He listens to his customers and he tries to do the best job that he can,” Puk says. “He’s really selling quite a bit of all the stuff that he makes. I’m so happy that he’s doing a great job.”

Her children still live in the neighborhood, and many of the local people she knows own their properties, so they haven’t moved away. But when asked if she feels any resentment about how the neighborhood has drastically changed, she went silent for a moment.

“No answer to that,” she says.

All in the families

‘You do such beautiful things’

Massih wears a close-cropped beard and glasses that make him look like a longtime Brooklyner, but in fact he is a relative newcomer. His parents moved their family from a small Lebanese fishing village about 10 miles from Tripoli to Canton, Massachusetts, a town of 23,000 people, where Massih’s father’s brother lived, about 15 miles from Boston. They were weary from living through multiple wars in the Middle East and believed that there would be economic opportunity in the U.S.

Massih’s father ran a gas station and his mother worked at a salon in Boston. Young Massih struggled socially in school in the predominantly white town, especially in the aftermath of 9/11, which triggered a wave of racism across the country.

But Massih had a passion for food to fall back on, and it propelled him all the way to a spot at the prestigious Culinary Institute of America in Hyde Park, New York. His professors helped him nab an internship at Wine & Spirits magazine and a line cook job at a spot in Chelsea Market.

Massih never planned on staying in New York. He was sure he would end up in the European food scene, which he says is more open to different food cultures.

“In America, you have to, you know, Americanize everything,” he said.

But after finishing his CIA degree, he stayed in New York. He opened a private catering business, and that took off. He ended up living in an Airbnb unit for six months in Williamsburg, and that’s when he found Greenpoint and fell in love with it, for the same reasons many of its residents love it: its older buildings and mom-and-pop shops that give it an old-school neighborhood feeling, and for its relatively isolated location, accessible only by the G subway line, keeps it less hectic than some other hyper-gentrified areas.

“A lot of people don’t come to Greenpoint, they say it’s out of the way. And I’m like, that’s fine. That’s okay with me,” he says, laughing.

He also loves what is left of the Polish legacy, including the people themselves—not that they actually eat in his store.

“I just love that Polish people like to eat Polish food. Maria won’t eat Middle Eastern. She’s always like ‘Oh, that yucky food,’” Massih says. “It’s the same with Lebanese people like in my hometown. There’s only Lebanese food, that’s all you can really find.”

After moving to Greenpoint, Massih began frequenting Maria’s Deli, what he called a “hidden gem.” His favorite orders were three specific sandwiches: A chicken cutlet on a hero, toasted with pepper jack, lettuce, tomato. “And she slices her lettuce and tomato on the slicer so they’re just so thin,” he says. On Fridays, a fish sandwich with tartar sauce, pickles, lettuce and tomato—if you got there in time. “And in between [my] events during the week, it was a hero with turkey, pepper jack, lettuce, tomato, mayo and mustard and pickles. It was the best meal for under $10.”

He began waving inside whenever he passed by, and sometimes he stopped in the deli just to say hello. Then, around the holidays a couple of years ago, he asked for Maria’s help in slicing a piece of beef tenderloin he had made for a catering client. She agreed to help, and they used her meat slicer together. He gave her his business card, and she was impressed by his website. The friendship was sealed.

“She said ‘Oh my god, you do such beautiful things,’” Massih said.

Garlic, lemon, oil and zero chocolate hummus

Massih gets his specialty items from Sahadi’s, the beloved Arab grocery store that was founded in Manhattan in 1898 and has had a presence in Brooklyn for more than 65 years. He gets occasional grateful Lebanese customers in his shop but knows that he largely isn’t serving Arab consumers. A New York University study from 2018 found that Greenpoint was 65.9 percent white, 20.7 percent Hispanic, 6.1 percent Asian and 3.9 percent Black. Brooklyn’s main Arab communities lay further south, in neighborhoods such as Bay Ridge.

But Philip Kayal, professor emeritus at Seton Hall University and editor of the book “A Community of Many Worlds: Arab Americans in New York City,” says that Brooklyn’s Arab populations splintered and spread out throughout the city—and to outer suburbs—decades ago. One thing keeping those who stayed in the area culturally connected, though, is their culinary heritage.

“They are as Americanized as everyone. In fact, as one of them says to me, ‘We’re all Americans now’,” Kayal says. “But what they like is the [Arab] food.”

New York’s Arab communities first settled in the financial district of lower Manhattan in the second half of the 19th century. They would soon migrate across the Brooklyn Bridge into Downtown Brooklyn, along Atlantic Avenue. In the 20th century, they went further south to Park Slope and then to Bay Ridge.

The first generations were mostly Syrian (Lebanon was part of Syria until 1940s) and mostly Christian, according to Kayal. After the 1950s, many joined in the great suburbanization wave, and Kayal says that they then quickly assimilated.

Their culinary legacy remains in Brooklyn—and as Massih points out, in outlining the reasons why he thinks he has been so successful, the demand for and interest in Arab food has spiked in recent decades.

“An ethnic group is accepted when its food is accepted,” says Kayal. “Period.”

Experimenters like Massih have gotten creative in taking the cuisine in new directions. For example, at the moment, his constantly changing menu includes “pita-dillas” (a quesadilla with a specific stringy type of Syrian cheese) and harissa-punctuated minestrone soup (a spicy take on the Italian staple). Still, he keeps the core elements of Lebanese cooking as a base throughout his dishes.

“Lemon, acidity, brightness, lots of seasoning. Olive oil, garlic, thyme, other Mediterranean flavors,” he says in describing the signature Lebanese palette.

Kayal, who has also co-authored a Syrian cookbook, said that he used to be upset about some of the loss of his culture’s tradition. For example, Syrians used to call pita bread “Syrian bread,” he said. But he has let it go. “That’s what happens over time,” he says.

Not everything passes, though.

“I’m sure you’ve noticed it: chocolate hummus. Chocolate hummus? I can’t even say it without getting nauseous,” he says.

A post-pandemic palate

While Greenpoint has seen many casualties in its creative food scene, Edy’s has thrived. Massih only requires a small, nimble crew in the small space, and he doesn’t need a wait staff. His food can be eaten on the go, in the fresh Covid-free air, or easily stored at home.

So naturally, he’s already looking forward, and he hopes to write a cookbook based on Edy’s Grocer’s recipes before he hits 30. He also might collaborate more with Puk, despite the fact that she doesn’t eat much non-Polish food. In fact, Puk brought up some ideas for Massih, including making his own potato pancakes in house. And although she can’t digest food with a lot of spice well, she’s going to make an effort to try more of his dishes. The chickpea eggplant stew is high on her list.

“You know, everybody has their own thing. Everybody likes a variety of food,” she says. “They don’t want to eat one kind of food, right?”

You might also like